скачать книгу бесплатно

All this is too close to Patrick’s experience of his oppressive father Charles Russ for coincidence, and the damaging effect he exerted in varying degrees on his offspring.

Alain’s return to Saint-Felíu arose from a summons to save his cousin Xavier, Uncle Hercule’s son, from what leading members of the family regard as a wholly inappropriate marriage. Alain himself ‘was sorry for Xavier … There was something very moving, in those days, in the sight of that proud, cold young man being humiliated and bully-ragged, and bearing it with a pale, masked fortitude.’

There can be no doubt that Xavier is a figure similarly deriving from Patrick’s character and experience, and the relationship between the dead father and his young son mirrors closely his own experience.

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of the bullying father figure is the way that the distorted relationship repeats itself in succeeding generations. Despite (or rather, because of) his harsh upbringing, Xavier in turn replicates the tyrant in his relationship with his own son Dédé. Although resolved at first to treat the child with the kindness his father never gave him, Xavier grows more and more dissatisfied with the boy, finding him intolerably weak, inadequate and sly. He tries educating Dédé himself, but the child’s foolish frivolity and sullen impertinence goad him into subjecting him to repeated beatings. While acknowledging that he had become the oppressor he so loathed in his father, Xavier confesses himself now incapable of acting otherwise.

This unsavoury episode unmistakably reflects both Patrick’s assessment of his own nature as a child, and his treatment of his son Richard, when he rashly attempted to tutor him in Wales in 1948–49. In this respect the experiment proved miserable for both father and son, as Patrick himself appears to have acknowledged following his arrival in France. What persuaded him to revisit that unhappy time, above all making Xavier excoriate his son in repellently disparaging terms? The explanation is, I suspect, that here as elsewhere Patrick utilized his writing on occasion as means of exorcizing his own shortcomings. He possessed no confidant beyond my mother, and even with her it seems unlikely that he found himself able to enlarge on actions he had come to regard with profound shame. He successively employed his three autobiographical novels (Three Bear Witness, The Catalans and Richard Temple) as vehicles for such confessions. The approach was presumably effective, as thereafter he appears to have felt he had effectively exhausted the theme.[fn18] (#litres_trial_promo)

The extremity of Xavier’s cruelty, and the inadequacy of his justification, are so hyperbolical as to suggest that Patrick expected readers to find the first as repugnant as the second was implausible. I suspect that, by grossly exaggerating his own misconduct, Patrick privately acknowledged it as indefensible. Its function was plainly cathartic. From a biographical point of view, the section in question (chapter IV) should be read in context. Xavier’s savagely frank account of his neglect and ill-treatment of his wife and son is set in the form of a confession, accompanied by expressed desire for absolution. Finding his formal confession to the town priest inadequate, he confides his lack of humanity and consequent fear of damnation to his sympathetic cousin Alain. Alain himself represents an alternative personification of Patrick: the gentle, inquisitive, sage adviser, which is how I for one found him when he confronted problems affecting those close to him. Chapters VIII and IX of The Catalans, recounting events from Alain’s perspective, derive almost verbatim from Patrick’s own experience.

Thus, one underlying function of The Catalans is to provide Patrick’s own confession. More than once in conversation with me he adverted to the Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, laying sardonic emphasis on the writer’s ingenuous account of his callous treatment of his children. Unsurprisingly, my mother observed that, on completion of Xavier’s bitter self-examination, Patrick found himself emotionally drained. ‘P. finished Chapter IV & got terribly depressed.’[9] (#litres_trial_promo)

The one person whom Patrick clearly would not have wished to understand the reality behind the father–son divide in The Catalans was his own son Richard. Equally, he must have appreciated the likelihood that the boy would read the book. As has already been seen, he followed his father’s literary career with filial pride. On learning in October 1953 of the book’s completion, he supplied a practical suggestion:

I am very glad to hear that you are having a holiday after completing the book. It seems to me that no sooner is one book out than you have finished another. Instead of writing with your hand why not get a tape machine or some such gadget or would that wreck everything? I do hope it comes out as you would wish it.

Next July, he enquired of my mother:

Has Dad heard anything of the last novel, and what is the title. Over in one shop (bookshop) I was peering round and I heard a customer ask for The Frozen Flame [the title of the British edition of The Catalans]. It was a terrific thrill to hear that, especially when I know my father wrote it.

His friend Bob Broeder remembers the sensation this aroused at school: ‘Richard brought in a book written by his father, the book was called “The Frozen Flame” by Patrick O’Brian. Richard was very proud of this and the whole class were now more than happy to be associated with a boy whose father was an author.’

As has been seen, once Patrick had renounced the ill-considered scheme of acting as his son’s teacher, a renunciation which coincided with Richard’s arrival at years of discretion, their relationship became unremittingly warm. The boy proved more and more capable of appreciating the literature that Patrick loved. In January 1952 he sent Richard copies of Thackeray’s Henry Esmond and W.H. Hudson’s Green Mansions. It is scarcely conceivable that in 1953 he would have published anything he believed likely to prove wounding to the boy. It seems he was confident that Xavier’s confession would be read purely as a literary construct.

Regarding the element of savage exaggeration in Xavier’s confession, it is further worth considering a linked episode (what Patrick himself terms ‘the parallel disaster’), in which his morbid concern to exaggerate the heinousness of his sin becomes yet more evident. Xavier acquires a dog, which proves disobedient and ill-behaved: so much so, that he thrashes it until he eventually ‘reduced it to a cowering, hysterical, incontinent, useless cur’.[10] (#litres_trial_promo)

Both Patrick and my mother were fond of dogs, and adored their own Welsh hunt terrier Buddug. In the early summer of 1952, while he was in the midst of writing The Catalans, my mother was obliged to visit England in pursuit of the disastrous Opel car. Always uneasy in her absence, Patrick became increasingly on edge as the days went by, and when after three weeks on the day of her expected return he received a telegram announcing its postponement to the following day, he found himself ‘feeling very much the pathetic poor one and generally angry. Poor Budd chose this one day to be bad, and I whipped her sore.’

The nature of her crime and the harshness of the punishment remain undisclosed. Two aspects are, however, clear. In the first place, Patrick was confessedly in an exceptional state of tension. Secondly, this was almost certainly the sole occasion on which the faithful Buddug was ever ‘whipped’. Not only is there no record in my mother’s diary of such an occurrence at any other time, but I am confident she would not have permitted it. It was surely this uncharacteristic episode that inspired Patrick’s awkwardly obtruded account of Xavier’s sadistic treatment of his dog. Patrick was deeply ashamed of having lost his temper with Buddug, and inserted the passage in his novel as a further form of exorcism or self-castigation.[fn19] (#litres_trial_promo)

Finally, on this significant topic, there remains Patrick’s passing allusion to the formal act of confession, which Xavier finds inadequately emollient when he repairs to the town curé, Father Sabatier. What he required was not a bland rite of forgiveness, but surgical exposure and extraction of the moral cancer of which his conscience accused him.

In 1960 he and my mother spent several months in London, coming every day to see me in hospital, where I was confined after a severe back operation. Despite the bitter circumstances of her divorce, my mother remained throughout her life deeply attached to the Russian Orthodox Church, in which she had married my father, and my sister and I were baptized. During this time she and Patrick became regular attenders at our Russian church in Emperor’s Gate, where they came to know and admire the parish priest. Father George Sheremetiev was a remarkable figure. Head of one of Russia’s greatest aristocratic families, he had previously been a cavalry officer in the Imperial Army. More importantly, he possessed a truly noble character: wise, perceptive, and holy in the truest sense. I regularly confessed to him, and like his other parishioners invariably found his admonitions perceptive and inspiring.

So impressed were my parents by Father George, that they asked him to marry them – their civil union of 1945 being unrecognized by the Church. Since Patrick would have appreciated from my mother how beneficial was the rite, it seems possible that he himself engaged in confession at this time – perhaps of an informal character. In the Aubrey–Maturin novels, Stephen Maturin is consistently portrayed as a Laodicean Catholic, verging on deism. However, after a particularly sumptuous dinner at Ashgrove Cottage, he congratulates Mrs Aubrey, adding jocularly: ‘When next I see Father George I shall have to admit to the sin of greed …’[11] (#litres_trial_promo) That Maturin had a confessor at all comes to the reader as a surprise, and that the latter bore so apparently English a name seems further anomalous (one would expect him to have been Irish or Catalan). On the one hand, we never read of Maturin’s participation in a Catholic service, while on the other numerous instances attest to Patrick’s pleasure in assigning the names of his acquaintances to characters in his books. Is this what happened here? Did Patrick eventually make the confession he had sought to express through his early novels?

I have dealt with the confessional element in The Catalans at some length, as it would be dangerously easy in the absence of knowledge of Patrick’s emotional state of mind to take Xavier’s rant against his son Dédé as a reflection of his own attitude towards his son Richard.[12] (#litres_trial_promo) In fact, given the warmth of their relationship at the time of writing, such an assumption appears wholly implaus ible. Furthermore, even had Patrick perversely decided to blackguard his own son in print, my mother would have registered the strongest objection. She loved the boy almost as much as she did his father. In December 1952, she wrote fondly: ‘Horrid letter from Mrs. Power [Elizabeth] about poor R., & letter from the school … Started V necked jersey for R. One of school complaints is that he wears my jersey, & Mrs P says he has lived in it since he got it. Cannot help feeling pleased.’

The year 1952 ended on a note of cautious optimism. My parents entertained high hopes for the success of The Catalans in the USA, and with luck in Britain too. Contemplating his next project, Patrick returned to notes he had compiled in the British Museum before the War for his planned book on medieval bestiaries. Hitherto the scheme had barely left the drawing board, but now as Christmas approached he completed a 10,000-word draft, which he planned to send with a synopsis of the remainder to his US and British publishers. In the event, it seems that their newly gained wealth allowed pleasurable distractions to interrupt the work sufficiently long for it to be abandoned permanently. It is a pity the draft has not survived, since his notes and provisional chapters in my possession indicate that Patrick could have produced an entertaining work on the subject.

All this is, however, to anticipate the book’s publication. It would be a year at least before The Catalans appeared in print, and what was to be done during the agonizing months of anticipation that lay ahead? Christmas drew near, with nothing happening as it should. On 19 December my mother was dismayed to find they had spent that year more than 60,000 francs on entertainment alone. The 22 of December proved worse: it was the ‘Black Day’, when they learned that the New Yorker had after all turned down the collection of stories submitted with such high hopes six weeks earlier. On Christmas Eve they received Richard’s school report: it likewise proved damning, provoking further depression. Christmas cards arrived, including one from Patrick’s stepmother Zoe, of whom he was very fond, and kind neighbours called with gifts. The festival was quietly enjoyed, but they decided they could not afford to give each other the customary presents.

Although the need for economy was pressing, they had managed to amass sufficient funds five days after Christmas to purchase for 100,000 francs a Citroën 2CV, popularly known as a ‘deux chevaux’. This was in due course to prove an even greater asset than the alternative prospect of an Andorran bolt-hole, which they now found themselves reluctantly obliged to abandon.

III (#ulink_a76134c5-399d-5984-8214-5f5ce8f83a3a)

New Home and New Family (#ulink_a76134c5-399d-5984-8214-5f5ce8f83a3a)

I descended a little on the Side of that delicious Valley, surveying it with a secret kind of Pleasure (though mix’d with other afflicting Thoughts) to think that this was all my own, that I was King and Lord of all this Country indefeasibly, and that I had a Right of Possession; and if I could convey it I might have it in Inheritance, as completely as any Lord of a Manor in England.

Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe

After more than three years’ stressful poverty in their little flat in Collioure, early in 1953 Patrick and my mother found their financial situation greatly improved by the warm reception his publishers accorded The Catalans. Since it had been submitted complete, substantial advances of $750 from Harcourt Brace in the States, and £100 from Hart-Davis in England, arrived at the beginning of the year.

Reviews proved encouraging. As a biographer I am primarily concerned with autobiographical aspects of the novel, but as a literary achievement it has gained high esteem. In 1991 the American novelist Stephen Becker wrote to Patrick:

I never told you how I enjoyed meeting an early (if older) version of Stephen [Maturin] in Alain Roig – and allow me to state that I found The Catalans not only first-rate but wise and moving … It is spacious and rich, and all of life is there – land and sea and sky, arts and sciences, food and drink, body and mind and spirit.

Constricted living conditions and the incessant cacophony of the narrow rue Arago had for some time made the couple long for a refuge in the countryside. Attempts to buy or build in Andorra had been frustrated, and despite encouraging praise for Patrick’s latest novel, their income remained too unpredictable to accumulate any capital of substance.

However, these unexpectedly large advances had at least enabled them to buy a car, which afforded means of escape from their stiflingly constrained existence. In the New Year, they found themselves in a position to fulfil this dream. They bought their little deux chevaux in Perpignan, which filled them with delight. Patrick noted that the number-plate included an M for Mary, and my mother ecstatically confided to her diary: ‘Car dépasses all our expectations in every way.’ Kind Tante Alice, the butcher, let them use her abattoir for a garage, and that day they drove the car up to the rim of the castle glacis, where it was formally photographed. Proud Buddug perched inside, no doubt foreseeing further camping expeditions.

The deux chevaux

If so, she was right. After a couple of days spent motoring happily around the neighbourhood, the three of them set forth on their long-deferred major expedition around the Iberian peninsula. On 21 January 1953 they drove over the Pyrenees by the pass at Le Perthus, arriving in Valencia two days later. Patrick was concerned that precious memories of a journey from which he hoped to profit might fade, and began keeping a detailed journal.

The moment they entered Spain, they were confronted by the homely ways of that then picturesque land, when solicitous customs officers asked them to take a stranded woman with them as far as Figueras. At Tarragona, Patrick was delighted by the prospect of the cathedral by night: ‘It was very much bigger than I had expected, and far nobler. Wonderful dramatic inner courts all lit by dim lanterns – bold low arches – theatrical staircases.’

He experienced an uncanny sensation, which was not new to him: ‘But I had, probably quite unnecessarily, the disagreeable impression of being stared at.’ This persistent fancy conceivably originated in his troubled childhood, when he never knew when the next thunderbolt might strike, whether from his moody father, or one of a succession of harsh governesses.

They took photographs with their new camera, of which I retain the negatives. Unfortunately, health problems continued to dog them. My mother suffered from a stomach complaint causing loss of appetite, and Patrick painfully twisted his ankle while photographing the Roman aqueduct.

The car, however, proved a sterling success: ‘A 2 CV. is certainly the car for Spain. Quite often the roads are fairly good (or have been so far) and then they suddenly degenerate into the most appalling pot-holed tracks as they pass through villages: there was one hole this afternoon that must have been a foot deep.’

In Tortosa, their progress was impeded by a ‘shocking assembly of carts: tiny donkey carts; carts drawn by one or two mules tandem – even three or one horse and a donkey in front: carts with barrels slung deep, carts with hoods and bodies made of wickerwork and carpet, all milling slowly about Tortosa.’

Nor did the Guardia Civil please Patrick: ‘nasty, impudent, overdressed, over-armed fellows, with a tin-god expression all over their faces’. However, as Patrick tended to view the British police with almost comparable distaste, his disparagement need perhaps not be taken over-literally. In any case, before long he encountered cause to moderate his view: ‘The Guardia Civil are strange souls: one whom we asked the way grew excited: he had the appearance of a man about to have a fit. Others seem normal enough, and even cheerful.’

Although largely apolitical by nature, Patrick, like many young people in the Thirties, had nurtured sympathy for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, and corresponding distaste for the regime of General Franco. While he never altered this view, he was frequently obliged to adjust his condemnation of the regime to the languid realities of everyday life in contemporary Spain.

He was greatly intrigued by remarkable contrasts with France, which struck them at almost every turn of their exploration. It used to be said that ‘Europe stops at the Pyrenees’, a dramatic contrast which both frustrated and intrigued Patrick:

I have not mentioned the countryside at all. There hardly is any, properly speaking. The country and the village are English inventions. Here there are plantations, barren stretches, small towns. There is something wrong with it all. I wish I could put my finger on it. The little towns and their inhabitants are shockingly rude, hard and brutal.

At the same time, Patrick admired the ‘vast plantations of olives (magnificent ancient trees on pink and grey soil) and carobs, and there are charming orange groves – much lower bushes than I had expected, much closer together and carrying twenty times as much fruit – as well as patches of good-looking plough.’

The people likewise appeared to belong to a distinct, all but timeless world. Stephen Maturin’s Catalan homeland would not be difficult to evoke, after glimpsing such vignettes as when they encountered ‘between Tortosa and Vinaróz the two old tall men in blue knee breeches, one smoking a pipe, with a black handkerchief round his head and white stockings, the other in blue stockings: Catalan espadrilles worn as far as here … gipsies, barefoot, with long gold earrings.’

Continuing southwards, it became apparent how few houses in the country possessed piped water: ‘We have found the reason for the amphorae. They are for taking water to houses, and they have no bottoms because they never stand up – always in baskets or stands. A terrible number of houses have no water. There is a cart with a barrel and a great many cruches: that is the mains.’

At Sorbas they came upon a community apparently living in caves tunnelled out of the soft rock. It being Sunday, thousands of them were moving along the road in their best clothes, ‘girls (some of them) with flowers in their hair, a young man bicycling with a guitar’.

Undisguised curiosity evinced by crowds in the town at the strangers’ arrival in their midst predictably angered Patrick, but the kingdom of Granada delighted him, with its exotic Moorish castles and ‘charming little red houses with red tiled roofs’.

Patrick’s childhood fascination with the exploration of exotic lands was constantly gratified. Arrived at the summit of a pass south of Valencia, ‘we could see an enormous moon-like country bare light green-gray rock in dusty white soil, jagged, arbitrary mountains in all directions, and below us a deep valley, terraced in swirling curves.’

Now, on the coast east of Malaga, they came upon Motril:

with its Moorish castle, perhaps the finest we have ever seen. And the backward view of Motril and the great headland beyond it, with the sky and the sea (lateen sails upon it) bluer than one can describe, with bits of the Sierra Nevada in the lefthand corner of the field of vision, that is a view, all right.

At Gibraltar they were briefly separated from Buddug, who was placed in quarantine in kennels at the end of the town. The friendly policeman who escorted them there also showed them HMS Vanguard lying in dock, and then took them to a pleasant hotel: ‘That evening we walked about until we were quite done up. It is an astonishing place: Spain still predominates, in spite of a very strong element of pre-war England with a dash of India.’

Unconscious seeds of Patrick’s future literary creations were being sown. He found Vanguard ‘very rosy and youthful’, admired the Georgian houses, and noted with approbation ‘Cheap Jack and Cheap John’s Stores’, together with Oxford marmalade.

While staying on the Rock, Patrick and my mother paid a brief visit to Tangiers. Crossing the strait, they saw dolphins, while ‘A kind mariner pointed out Cape Trafalgar.’ On disembarking, they found themselves in a world still more enticingly exotic than Spain: ‘We wandered up a street where everybody seemed to be going, a crowded street. But crowded with such people. Moors in djellabahs and slippers, pale Moors like Europeans but with fezzes, slim veiled women veiled [sic], blue or white …’

Delighted with their brief but memorable visit, they returned to be regaled by affectionate dolphins: ‘Not only did they skip and play, but they came right into the ship and swam immediately along the cutwater, having immense fun with the rush of the water. They kept pace effortlessly, turning, rolling, jostling one another.’

Details of these and other curious encounters are frequently accompanied by Patrick’s sketches in the margins of his journal. Back in Gibraltar they spent a whole afternoon searching for a birthday present for the growing Richard, before they eventually succeeded in hunting down a leather-cased shaving kit. At dusk they climbed the Rock to view the apes, and next morning set off for Cadiz – which regrettably proved ‘the rudest town so far, the ugliest and the dirtiest’. Patrick’s resolve to drink sherry at Jerez was frustrated, when a café could only provide him with ‘something just as good’. In fact the mysterious beverage proved ‘quite good’, while an awkward confrontation was narrowly avoided:

While we were drinking it up – precious little there was – I had my back to the street, facing M. She told me afterwards that all the time there were men, respectably dressed men, leering at her from behind my back, and making gestures of invitation. Perhaps it was as well that I did not see them, because I was feeling profoundly depressed and bloody-minded, and there would have been a scene.

After exploring the region around Malaga, they returned to Motril. By then they decided they had endured all they needed of Spain: ‘It is impossible to say how agreeable Collioure appeared in the sordid brutality of Motril.’

Patrick invariably grew restless and ill-at-ease when away from their snug home for long, but buoyed up by the prospect of return ‘we began to hope that we were mistaken and that the inland Andalusian was a decent creature’. A visit to the Alhambra aroused Patrick’s ‘surprise at the extraordinary good taste of the Spanish authorities’. Crossing the mountains en route for Cordoba, he enthused over the presence of a number of magnificent red kite, noting too that: ‘Here the little irises began all along the side of the road, on the hill leading out of Jaen, and for hundreds of miles after.’ Cordoba’s mosque ‘was utterly dull from outside … but inside – dear Lord, what grandeur’.

Even this splendour was eclipsed on their return to Seville:

We did see the Cathedral at once, and that was a glorious sight: it seemed to me profoundly religious, and very, very much more important than Córdoba. The severe, clean austerity of what we might call the furnishings was intensely gratifying. No geegaws at all, except Columbus’ tomb. (And that, being alone, was impressive too, in its way).

After a night in ‘the cheapest (and rudest)’ hotel in town, they revisited the cathedral, where Patrick observed the relics, including ‘a piece of Isidore’ (the seventh-century Spanish scholar), about whom he had intended to write when preparing his book of bestiaries before the War.

After obtaining paperwork from the Portuguese consul, they drove to Huelva and crossed into Portugal by boat across ‘the brown and yellow Guadiana, heaving gently, with tremendous rain beating down upon the mariners and dribbling through the hood’. On disembarking, ‘The rain stopped suddenly and a complete double rainbow stood on the Spanish side of the river: an omen, I trust.’

It appears to have been, for within hours they found Portugal more congenial than Spain:[fn1] (#litres_trial_promo)

All the way we kept remarking the extraordinary difference the frontier had made – little ugly crudely painted houses, blood red and ochre or raw blue, perforated chimneys like cast iron stoves, ugly, barefoot people, intense cultivation, comparatively dull country, no Guardia Civil, no Franco Franco Franco (spontaneous enthusiasm in durable official paint), no rude staring, no excessive poverty. Even the gipsies … looked different: they had not that pariah air, and they wore skirts to the ground and wooden, heel-less slippers. But the greatest difference was at Lagos: not only was there no wild-beasting at all, but when we were walking on the sand we said good-day to some ordinary youths. They took off their caps and bowed.

In Lagos they were taken to watch the masquerade taking place in various clubs. So great was the crush, that they were obliged to hover in doorways. But Patrick found the masks ‘very funny indeed, almost all of them’. They learned that the clubs were graded according to social status: ‘The last was the top, and there, it is true, there were some solemn old gentlemen dancing with masked females. It was unbelievable that so many people should inhabit one small town, or rather village.’

That afternoon they paid their respects to one of England’s great naval victories, sitting in a shelter overlooking Cape St Vincent, an 800-foot cliff plunging sheer below them. On the way they passed a working windmill. Ever fascinated by technology of the past, Patrick stopped to photograph it. ‘The miller, a rough-looking but kind and sensible man, invited us in, and explained his mill, made us plunge our hands in the flour, moved the top, stopped the sails, and did everything he could to be agreeable – went to a great deal of trouble.’

Patrick sketched careful diagrams of the workings of the sails and internal machinery. During a digression to Faro he likewise drew some fishing boats, being particularly taken with the prophylactic eye (with splendid eyebrow) painted on each boat’s bow, a mysterious mop of wool adorning the prow.

The Portugal visited by Patrick appeared little changed since Wellington’s day. Patrick noted with pleased surprise: ‘No advertisement posters yet in Portugal. None at all.’ On the road to Lisbon:

As soon as we passed out of the Algarve the hideous man’s hat (black) worn over cotton scarf began to vanish – women here wear velour hat, flattened, with broad coloured ribbon or wide straw hat. Shoes rare – stockings cut at ankle for bare foot. Men in woollen stockings caps dangling to neck. Pleasant boy’s faces under black hats (bow behind).

Lisbon proved well up to expectation: ‘The sudden view of the Tagus with Lisbon the other side was as grand as anything I have ever seen.’ After strolling into the centre, ‘we wandered along the river and admired a square-rigged Portuguese naval training ship’. Amid the capital’s architectural glories, my mother was rewarded by a glimpse of ‘a windscreen wiper for sale called Little Bugger’.

Making their way across country to the northern frontier, the travellers encountered weather and countryside less congenial. Back in Spain, Patrick attended mass at Santiago, but was strangely unimpressed by town or cathedral. Passing Corunna, they became alarmingly trapped for a while in a snowdrift beyond Villalba. Fortunately the summit of the hill proved not far, and Patrick stumbled behind on foot as my mother gingerly enticed the car towards it. ‘When we reached the sea at Ribadeo (a very pleasant looking place … hundreds of duck down on the water; tufted duck mostly – and every promise of trout, if not of salmon too) we suddenly saw the Cordillera, pure white with deep snow.’

Passing through Basque country, where ‘the red berets were worn quite naturally’, they came to Guernica, scene of an infamous German air raid during the Civil War – ‘and a melancholy sight it was – every building new, almost, and still a number of ruins’. Driving as fast as they could along precipitous coastal roads, frequently blocked by landslides, they finally gained the frontier at Irun. ‘A toll-bridge, and we were in France again. French customs pleasant, sensible – Budd’s utter fury at their touching sacred car and even prodding food parcels.’

The fine French roads sped them across country, and on 18 February 1953, ‘in spite of the snow we were home at half past five, with an enormous post’. The news was generally good, especially a welcome cheque for £100 from Rupert Hart-Davis. Their neighbours the Rimbauds were warmly welcoming, as was their cat Pussit Tassit (who had managed to become pregnant). ‘How pleasant it is, our own place, and how queer the familiarity.’ Patrick calculated that they had travelled 3,674 miles, at a total motoring cost of 17,236 francs (about £15).

They had been away from home for a month, the longest foreign tour (not counting England) in which they ever engaged. Although there is little direct evidence of the use to which it may have been applied in his literary work,[fn2] (#litres_trial_promo) there can be no doubt that Patrick’s extended immersion into the dramatically archaic world of Spain and Portugal as it was then played a significant function in conferring the astonishing gift for immersion in past worlds which represents so marked an aspect of his historical fiction. Nearly thirty years later he came upon his diary record, noting wistfully: ‘I read abt our journey in darkest Spain 1953 – forgotten or misremembered details – how it all comes to life!’

At the time, however, it seems that Patrick was pondering further work on contemporary themes. Shortly after their return, he reverted to his planned series of short stories. In March he wrote ‘The Walker’, and on 7 April my mother ‘Sent off The Walker, The Crier, The Silent Woman & The Tailor to C[urtis]B[rown] New York.’ Unfortunately, the last three tales have not survived.

Although the journey around the Iberian peninsula had proved both entertaining and (it was hoped) an inspiring source for future writing, before long Patrick and my mother found themselves reverting to continued frustration over their mode of existence in their cramped quarters in the rue Arago. During a brisk March walk up to the Madeloc tower, they ‘Agreed on discontent with present way of life: sick of peasants so close to our life, need garden & hens & bees so as to be able really to save mon[ey].’

Time appeared slipping by, without adequate achievement to slow its passage. In April Patrick received news from his family in England that his once-dreaded giant of a father had suffered a stroke. Patrick, who throughout his life kept in regular touch with his family, must already have been aware of his declining health. A profoundly formative era of his past, wretched though it had largely been, appeared to be approaching extinction within the vortex of vanished years. It was at this time (1953) that he began work on an autobiographical novel, which in its final form completed years later evoked years of childhood and adolescence, filling him with a complex amalgam of nostalgia, resentment, and shame.[fn3] (#litres_trial_promo) His work on this project, which preoccupied him intermittently over the next two years, will be recounted in due course. As ever, my mother played a strongly supportive role in the writing, and was deservedly gratified by Patrick’s heartfelt acknowledgement: ‘P. gave me immense pleasure by saying he values me most as critic.’

Further matter for concern arose again concerning Patrick’s son Richard. Poor reports from school, together with a ‘horrible letter’ from his mother, persuaded Patrick and my mother to ‘decide to take R. & have him work for the school cert. with us, by a correspondence course’. The project was, however, postponed for the present, until July when Richard arrived for his summer holiday at Collioure.

Enterprising as ever, he ignored his mother’s apprehensive objections, cycling all the way from Dieppe, to whose Poste Restante my mother transmitted 5,000 francs for travelling expenses.[fn4] (#litres_trial_promo) Equipped only with a school atlas as guide, Richard arrived cheerful and excited at the beginning of August.

Collioure proved particularly lively and sociable on this occasion. Within days of Richard’s arrival he made a memorable contact. Two schoolmistresses from England came to stay in the town, accompanied by four of their pupils. One of the pair, Mary Burkett, met my parents and became a friend for some years (she had an aunt living near Collioure). It was not long before Richard became friends with the schoolgirls, and one in particular attracted his close attention.

One evening my mother invited the girls to dinner, after which Richard and another boy named Pat entertained their new friends:

All day preparing dinner (Spanish rice). V. successful, whole school. They are wonderfully pleasant young things. After dinner Pat came, & he & Richard escorted Susan, Wendy, Anne-Louise & Jill to fair. R. home at midnight. He prefers Susan, & Pat Wendy. Susan is the best.

Thereafter romance blossomed, and Richard and Susan were together every day until 26 August, when sadly the school party returned to England. No sooner had they been waved off at Perpignan railway station than ‘R. wrote to Susan: says he is going to see her the day after he reaches London.’ They continued in touch, until on 10 September Richard himself returned to England:

R. had one [letter] from Sue & ever since (2 pm) has been writing back to her. P. took R’s bike to P. Vendres & sent it off. Saw R. off at Port-Vendres very sadly, in great wind & with black & purple sky. R. said this has been his best holiday. The house is so sad without him.

Richard had always loved his holidays in Collioure, but this time there had been especial reason for enjoyment. On his return to London, he wrote: ‘Thank you both so very much for the best holiday that I have ever had. And it really was the best.’ He and Susan had now become fast friends:

The [Cardinal Vaughan] school’s secretary stopped me and asked whether the Mr O’Brian that had written The Catalans[fn5] (#litres_trial_promo) was my father. With huge pride I said ‘Yes’. Susan has shown me a revue of the Frozen Flame [the book’s British title] and it looked very good …

Now I am going to begin. Susan sent me a card saying that would I like to hear a lecture on ‘Everest’. Well Susan brought her two brothers and there [sic] two friends to hear the lecture … Her brothers are extremely pleasant to say the very least. And the lecture given by Hunt, Edmund Hillary and Low was absolutely superb …

Susan also invited me down to their house for lunch and tea. Was I scared, as at the last tea-party I sat down on the tea-pot. Her parents are wonderful, they really are. Their house, gee. Susan had told me that it was a small thing. Sixteen rooms and grounds that have a tennis court, flower garden kitchen garden, goat-house and hen house and a tool shed.

Susan’s father, Paul Hodder-Williams, a director of the publishing firm of Hodder & Stoughton, was editor of Sir John Hunt’s bestseller The Ascent of Everest, which he was shortly to publish. The parents’ wealth and status in no way inhibited their friendliness to the shy but enthusiastic sixteen-year-old boy. As for their pretty daughter:

Seeing Susan again was terrific only her hair is a bit darker. She has gone back to school today. Ah. I asked her parents if I could take her out during the Christmas holidays, and to my delight they immediately said ‘Yes’, so that’s quite all right. Quite where to take her I don’t really know. Please could I have every suggestion however mad? She likes her bracelet. Soon she will be sending some of those photos that the girls took of her, they should be marvellous. She is still the same. What a wonderful girl she is.

In December my mother stayed with her parents in Chelsea, when she saw much of Richard. For him the outstanding moment was when she took him to see Richard Burton and Claire Bloom acting in Hamlet at the Old Vic. This was Richard’s first visit to the theatre, and he was enraptured by the ‘perfect’ production. Two days later he took my mother to the cinema, and a couple of days were spent in hunting down his first grown-up suit.

At Christmas Susan sent my parents a copy of Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Verses on behalf of her friends and their two schoolmistresses, thanking them again for their kindness throughout their stay at Collioure. Nothing more is recorded of this charming romance, which graphically illustrates my mother’s and Patrick’s talent for empathy with the young, especially in their amours. Within a few years they were to evince similar sympathy for me and my occasionally troubled youthful love affairs.

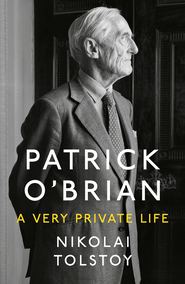

It was in August 1953 that ‘Mary [Burkett] took photographs of P for H[arper’s].B[azaar]. (only one came out, but it is very good).’

Eventually, as tended on occasion to occur, Patrick took mysterious offence at something Mary Burkett may or may not have done. In later years I came to know her, when I was able to reassure her that it was unlikely to have been in consequence of any particular offence on her part. Patrick’s writing was not going well at the time, and it was clearly in large part the strain which frequently made it hard for him to sustain close friendships at a remove. A chapter of Mary Burkett’s privately published biography is devoted to their friendship. Unfortunately, it includes much factual misrepresentation, despite the fact that when in August 2005 I stayed at her lovely home Isel House in the Lake District, we talked nostalgically of those long-departed days.[1] (#litres_trial_promo)

A gift Mary had brought from England to Collioure long outlasted their friendship. On 21 July 1954 my mother cryptically recorded that ‘Mary Burkett arrived about 10, she brought us book-binding stuff.’ This was a parcel of early legal documents, which she had saved at a solicitor’s office clearance. Patrick tended to make heavy use of his beloved leather-bound books, with the result that their spines often became badly worn. In later years he replaced the damaged ones with strips cut from the sturdy paper used by seventeenth-century lawyers.

Patrick, photographed by Mary Burkett in 1953

Books so repaired, reposing comfortably on the bookshelves looking down upon me as I write, include his much-loved set of Johnson’s Lives of the Poets (1824), Camden’s History of The most Renowned and Victorious Princess Elizabeth, Late Queen of England (1675), Cowley’s Works (1681) and Thomas Stanley’s History of Philosophy (1743). Of particular interest is Patrick’s copy of William Burney, A New Universal Dictionary of the Marine (London, 1815), upon which he largely relied for his understanding of the workings of the Royal Navy in the eighteenth century, before he subsequently acquired the yet more apt Falconer’s An Universal Dictionary of the Marine (1769). Normally such amateurish repairs would detract greatly from the collector’s value of the books. However, in this case I find them enhanced, being constantly reminded of the pleasure they afforded their impassioned owner.

The year 1954 opened with an accruing worry inflicted on the hard-tried couple, whose financial situation remained precarious as ever. Patrick’s son Richard had always encountered difficulty with academic work. He would be seventeen in February, and the time had approached when he must consider a career. His ambition to enrol at the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth having proved sadly abortive, it became essential to find a satisfactory alternative. It was a worrying prospect, not alleviated when on 15 January my mother noted: ‘R’s report came: very sad.’

However, their overriding concern was with his well-being. Richard and his friend Bob Broeder had become cycling enthusiasts, which involved them in many adventurous exploits – of which their parents fortunately remained unaware. On occasion they would ride as far as Brighton, a hundred-mile round journey, and took to recklessly hurtling at some 60 mph down precipitous Reigate Hill, after removing their brakes. Bob recalls that: