Полная версия:

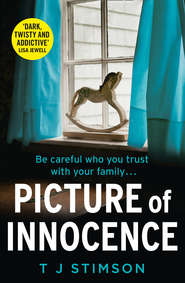

Picture of Innocence

PICTURE OF INNOCENCE

T J Stimson

Copyright

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © T J Stimson 2019

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2019

Cover photograph © Tom Hogan/Plain Picture

T J Stimson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008298203

Ebook Edition © [month] 2019 ISBN: 9780008298210

Version: 2019-03-13

Dedication

For my nephews,

George, Harry and Oliver.

Your Daddy would be so proud of you.

Charles Michael Francis Stimson

1974–2015

Epigraph

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Now

Four weeks earlier

Chapter 1: Monday 11.00 p.m.

Chapter 2: Tuesday 7.20 a.m.

Chapter 3: Tuesday 10.00 a.m.

Lydia

Chapter 4: Wednesday 7.30 a.m.

Chapter 5: Wednesday 10.00 a.m.

Chapter 6: Friday 11.30 a.m.

Chapter 7: Saturday 2.00 a.m.

Chapter 8: Saturday 7.30 a.m.

Lydia

Chapter 9: Saturday 8.30 a.m.

Chapter 10: Saturday 10.00 a.m.

Chapter 11: Saturday 11.00 a.m.

Lydia

Chapter 12: Saturday noon

Chapter 13: Sunday 6.30 a.m.

Chapter 14: Tuesday 2.00 p.m.

Chapter 15: Wednesday 8.00 a.m.

Lydia

Chapter 16: Wednesday 11.30 a.m.

Chapter 17: Wednesday 2.00 p.m.

Chapter 18: Wednesday 4.30 p.m.

Lydia

Chapter 19: Thursday 9.00 a.m.

Chapter 20: Thursday 10.00 a.m.

Lydia

Chapter 21: Saturday 10.00 a.m.

Chapter 22: Saturday 11.30 a.m.

Lydia

Chapter 23: Sunday 2.30 p.m.

Chapter 24: Monday 12.30 p.m.

Lydia

Chapter 25: Monday 11.30 p.m.

Chapter 26: Tuesday 2.30 p.m.

Lydia

Chapter 27: Tuesday 6.00 p.m.

Chapter 28: Tuesday 8.30 p.m.

Lydia

Chapter 29: Tuesday 9.30 p.m.

Lydia

Chapter 30: Thursday 4.30 p.m.

Lydia

Chapter 31: Thursday 5.30 p.m.

Chapter 32: Thursday 7.30 p.m.

Chapter 33: Thursday 8.00 p.m.

Chapter 34: Friday 2.00 a.m.

Chapter 35: Saturday 7.00 a.m.

Chapter 36: Saturday 8.00 a.m.

Chapter 37: Saturday 2.15 p.m.

Chapter 38: Sunday 9.55 a.m.

Chapter 39: Sunday 1.30 p.m.

Chapter 40: Tuesday 7.30 a.m.

Chapter 41: Thursday 3.00 p.m.

Chapter 42: Friday 2.30 p.m.

Chapter 43: Friday 4.30 p.m.

Chapter 44: Friday 6.30 p.m.

Chapter 45: The present

Six months later

Chapter 46: Saturday 11.00 a.m.

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Now

I crawl back into bed and stare blindly up into the darkness. I won’t sleep; not tonight, not for many nights to come. I doubt I’ll ever sleep soundly again.

I start to shake. The adrenalin that brought me this far suddenly drains away and I begin to shiver so violently my muscles cramp. I press my fist against my mouth to still the chatter of my teeth. If I had anything left in my stomach, I would be sick again.

I’ve always thought of myself as a fundamentally good person. I’m not perfect, but I’ve spent a lifetime trying to do the right thing. I rescue spiders from the bath; I stop traffic to let a mother lead her row of ducklings across the road. I literally wouldn’t hurt a fly. A month ago, I’d never have believed myself capable of killing a mouse, never mind murdering another human being in cold blood.

But human nature has an infinite capacity to surprise.

We teach our children to fear dark alleys and strangers, but the real danger is much closer to home. You’re more than twice as likely to be murdered by someone you love than by someone you’ve never met. If you’re a child, it’s nearer three times. If you want a reason to be scared, look in the mirror.

Evil doesn’t have two horns and a tail. It’s ordinary, just like me.

Those jealous husbands who bludgeon their wives to death, the women who smother their babies, the estranged fathers who lock their children in the car and connect the exhaust. Ordinary men and women, all of them.

Just like me.

Chapter 1

Monday 11.00 p.m.

Maddie opened her eyes. It was dark; she struggled to orient herself as her vision adjusted to the gloom. She was in the nursery: she could just make out the silhouette of Noah’s cot. She had no idea how she’d got here. When she groped for the memory, it’d been wiped clean.

Her throat felt raw and hoarse, as if she’d been screaming. She moistened her lips, and tasted blood. Shocked, she touched her mouth, then looked down to see a dark smear on her fingertips. Had she fallen? She and Lucas had been arguing, she remembered that, though she couldn’t remember what the row was about. Had she stormed out of the room? Walked into a door?

She closed her eyes again and thought back to the last thing she could remember. She and Lucas had been upstairs, in their bedroom; her husband had just come out of the shower, spraying her with water as he towelled his thick, dark hair. Her heart had skipped a beat, as it always did when she saw him naked, even after six years of marriage, the intensity of her craving for him almost frightening her as she’d pulled him hungrily onto the bed.

She suddenly remembered: with perfect timing, the baby monitor on the bedside table had flared into life, an arc of furious red lights illuminating the bedroom. Not that the alarm had been necessary; Noah’s screams had echoed from the adjoining nursery, loud enough to wake everyone in the house, and probably everyone on the street, too.

Lucas had told her to let the baby cry. That’s why they had been arguing. Lucas had told her to leave Noah. It was just colic, he’d grow out of it – Come on, Maddie, just leave him …

And then her memory simply snapped in half, like a spool of tape at the end of the reel.

She exhaled in frustration. She had no way of knowing if she and Lucas had argued five minutes or five hours ago. The doctor said her memory lapses were normal, the product of exhaustion and the pills she was on. Nothing to worry about, he said. Nothing to do with what had happened before. She had three children, two of them under three: of course she was tired! Of course she forgot things! It’d all sort itself out if she was patient.

But it was happening more and more often: whole blocks of time, lost for good. It’d started around the time she’d found out she was expecting Noah, and had got worse in the nine weeks since his birth. No one watching her would notice there was anything wrong. She didn’t collapse or black out. But suddenly, in the middle of doing something, she would find she couldn’t remember what had just happened. A few seconds, or a few minutes of her life, gone forever. Her memory stuttered and skipped like a home movie, with blank spaces where pivotal scenes should be.

All she could remember tonight was the baby screaming, Lucas rolling away from her in frustration …

Noah wasn’t screaming now.

Galvanised by fear, she sat up and switched on the nightlight. She’d been holding him in her arms, but they were empty now. He wasn’t in his cot, he wasn’t on the floor. She couldn’t see him. She leaped up from the chair in panic, and then she saw him, crushed against the back of the seat. Somehow, he’d slipped out of her arms and become wedged between her hip and the side of the rocking chair, his vulnerable head pressed against the wooden spindles. Terror flooded her as she crouched on the floor and pulled his limp body onto her lap. His eyes were closed, his face still and pale, except for the vivid red imprint of the chair on his cheek.

She put her ear to his chest, praying for a heartbeat, pleading with a God she didn’t believe in. Please let him be OK. Please let him be OK.

Abruptly, Noah squirmed in her arms and let out an indignant but healthy cry. Maddie gave a strangled half-sob, half-laugh and snatched him up against her shoulder, her throat clogged with grateful tears.

‘Mummy?’

She practically jumped out of her skin. Nine-year-old Emily stood silhouetted in the doorway to the hall, her long nightdress giving her the air of a Victorian ghost.

‘Emily! Did Noah wake you?’

Her daughter nodded sleepily. ‘Can’t you make him stop, Mummy? I’m so tired.’

Maddie felt thick-tongued and groggy, as if she’d awoken from a drugged sleep. ‘Me, too, darling.’

Emily leaned against the rocking chair, her long, fair hair brushing against her brother’s furious scarlet face. The screaming baby grabbed a fistful in his tiny hand. ‘Can’t you give him some medicine or something?’

‘It doesn’t really help.’ Maddie gently freed her daughter’s hair from Noah’s grasp. ‘Go back to bed, Em. You’ve got school in the morning.’

‘I feel hot.’

She felt her daughter’s forehead. A little warm, but not enough to worry about. ‘Get some sleep, and you’ll be fine.’

‘I can’t sleep. He’s too noisy.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Maddie sighed, standing up and switching Noah to the other shoulder. ‘There’s not much I can do. Why don’t you try putting a pillow over your ears?’

‘Nothing blocks that out.’

Maddie closed the door as Emily stomped back down the corridor to her own room, praying the noise didn’t wake two-year-old Jacob too. She paced the small nursery, shushing and rocking the baby, so bone-tired she was almost asleep on her feet. She felt ninety-two, not thirty-two. Her back ached, and her eyes were raw and gritty. Her breasts throbbed with the need to nurse, but when she sat down to try, Noah stubbornly refused to feed.

She got up again and pressed her forehead against the cool glass of the nursery window, looking down into the inky garden as she jiggled Noah up and down in an attempt to soothe him. There was nothing lonelier than being awake when everyone else was asleep.

Unplanned isn’t the same as unwanted, Lucas had said. But he was wrong. Noah hadn’t been a happy accident, not for her.

Oh, she loved him beyond words now he was here, there was no question of that. She’d walk over hot coals for him, of course she would. She was his mother; there was nothing she wouldn’t do for any one of her children. But it’d taken everything she’d had to put herself back together after Jacob, and she hadn’t been sure she’d had it in her to do it again.

Emily had been an easy infant; even though Maddie had, quite literally, been left holding the baby when her daughter’s father had been killed five months into the pregnancy, she’d coped better with single motherhood than she’d expected. It’d helped that Emily had apparently read the textbook on how to be the perfect newborn. She fed every four hours. She smiled on cue at six weeks. She put on exactly the right amount of weight and hit all the correct percentiles for her age. Maddie had taken Emily to the animal sanctuary where she worked, and her daughter had cooed beatifically in her pram in the sunshine for hours while Maddie groomed horses and mucked out stables. She’d listened to other mothers at her postnatal classes complaining about mastitis and sleepless nights and wondered what their problem was.

Her mistake, she’d realised when Jacob was born, had been having her easy baby first. She’d confidently assumed motherhood would be just as straightforward second time around, especially since this time she didn’t have to do it all alone.

She couldn’t have been more wrong.

Chapter 2

Tuesday 7.20 a.m.

Lucas noticed the red marks on Noah’s face as soon as he came into the kitchen. He crouched down beside the baby’s bouncer, stroking Noah’s cheek with his thumb. ‘What happened to you, kiddo?’

Maddie busied herself with Jacob’s Weetabix so her husband couldn’t see her face, too afraid to admit she’d flaked out last night with their baby in her arms. Thank God Noah was none the worse for wear, apart from the marks, which were already starting to go. ‘I think he got himself wedged in a corner of his cot,’ she fibbed. ‘He must’ve pushed his face up against the bars.’

‘Poor little bugger.’

‘It’ll fade.’

Lucas dropped a kiss on Noah’s head, then straightened up and started emptying the dishwasher. Maddie surreptitiously watched him as she stirred Jacob’s cereal. She never tired of seeing her husband do simple domestic tasks like make coffee or empty the bin. Part of it was sheer novelty; her mother, Sarah, had raised her alone after her father’s death when she was two, so she wasn’t used to seeing a man help out around the house.

She also found it strangely erotic to watch her big bear of a husband wipe down a kitchen counter or neatly fold tea towels. At six-feet-five, he dwarfed everything he touched; the plates seemed like toys from Emily’s tea set in his huge hands. She and Lucas were a marriage of opposites on many levels, not least of them physical. She barely scraped five-feet-two, the top of her head just level with his broad chest. He was dark-haired to her sandy blonde, brown-eyed to her blue. He could have picked her up and tucked her under one massive arm. She couldn’t even get him to roll over in bed when he snored.

But despite his mountain-man appearance, Lucas was actually a cerebral, dreamy, indoor sort of man; his weekdays were spent at a drawing board, designing buildings for a small, local architectural firm, and in his downtime at weekends he did crosswords or read obscure Russian novels. For Maddie, on the other hand, there was no ‘weekday’ or ‘weekend’; she ran an animal sanctuary, which was a twenty-four-seven commitment. She didn’t have time to worry about what to wear, never mind what to read; most mornings she flung on the same filthy jodhpurs from yesterday and dragged her hair back into an unwashed ponytail. Her hands were callused from years of mucking out stables and lunging ponies, her fingernails broken and dirty. If she put on a skirt, it was a noteworthy event.

No one who met Lucas and her separately would match them as a couple. And yet theirs had been a whirlwind romance, love at first sight. Four months after meeting in the jury room at Lewes Crown Court, they were married. Six years on, in defiance of the friends who’d said she had no idea what she was rushing into, they were as much in love as ever.

She’d known, of course, that Lucas must have baggage; as her best friend Jayne succinctly put it, no one got to thirty-four without a few fuck-ups along the way. But, recklessly, she hadn’t been interested in his past; only in their future, together. Even now, she still knew very little about his life before they’d met. He rarely talked about his childhood or adolescence, for good reason. When he was just thirteen, he’d rescued his four-year-old sister Candace from the house fire that had killed both their parents. Looking back now, Maddie wondered if their shocking bereavements had been part of what drew them together. She understood better than most that to survive tragedy, sometimes you had to close the door on the past.

But her first instincts had been right. He was a good husband, a wonderful father and stepfather. He brought her a cup of tea in bed every morning and rubbed her feet at night when she was tired. And they’d made beautiful children together, she thought fondly, as she put Jacob’s breakfast on the high chair in front of him. Both their sons were a perfect blend of the two of them, with ruddy chestnut hair and hazel eyes. Only Emily looked like she didn’t belong. She was growing more like her biological father with every passing year.

As she stirred the lumps out of Jacob’s cereal, Maddie felt an unexpected rush of tears. She blinked them back, cursing the pregnancy hormones that left her so vulnerable. Emily’s father, Benjamin, had been her first boyfriend, a veterinary student in his final year at the same college as she when they’d met. Quiet and painfully shy, Maddie had always found it hard to make friends, having been raised by a widowed mother too busy with her charitable causes to have time to show Maddie how to have fun. At twenty-one, she’d never even been on a date until Benjamin asked her to join him at a lecture about animal husbandry.

Somehow, Benjamin had got under her skin. Theirs had been a gentle, low-key relationship, a slow burn born of shared interests and companionship. It wasn’t love, exactly, but it was warm and reassuring and safe. Eight months after they’d met, she’d lost her virginity to him in an encounter that, like the relationship itself, was unremarkable but quietly satisfying.

The pregnancy a year later had been a complete accident. To her surprise, Benjamin had been thrilled. They’d both graduated college by then, and while she made next to nothing at the sanctuary, he was earning enough as a small animal vet to look after them both. He bought dozens of books on fatherhood and had picked out names – Emily for a girl, Charlie for a boy – before Maddie had been for her first scan. He was so excited about becoming a father, his enthusiasm was contagious.

He’d died in one of those stupid accidents that should never have happened, skidding on wet leaves on a country road one dark November afternoon. No one else was even involved. Maddie herself had been out shopping for baby clothes when it happened. She would never forget turning into their street and seeing the police car parked outside their flat. She’d known, instantly, that Benjamin was dead.

She hadn’t fallen apart, because she’d had the baby to think of. She’d put her head down and concentrated on Emily and the sanctuary, never permitting herself to think about what could have been. She had her daughter, and her horses. For four years, it’d been enough.

And then she’d met Lucas, as unlike Benjamin as it was possible to be. Their relationship had been a coup de foudre, stars and fireworks and meteor showers. She fell in love not just with him but with the person she became when she was with him: confident, witty, amusing. When he asked her to marry him, she didn’t hesitate. Lucas had saved her, in every way a person could be saved.

Maddie spooned a mouthful of Weetabix into Jacob’s mouth and wiped his chin. She’d been so excited at the thought of having his baby, of seeing what the combination of his and her genes would produce. When Jacob was born, three years after they married, she’d expected him to slot into their lives without a ripple, the way Emily had. But from the start, he’d been hungrier and more fretful than his sister. He’d refused to latch on properly and had quickly lost weight. Then she’d developed mastitis. At the midwife’s insistence, she’d switched to formula, feeling like a failure, her anxiety and exhaustion unsettling Jacob even further in a vicious circle. And then, just as suddenly, her agitation and nerves had been replaced by an emotional numbness that was far more troubling.

It was obvious, even to her, that there was a huge difference between not caring about anything and not being able to care. But she found herself incapable of doing anything about it. There’d been days when Lucas had left to take Emily to school in the morning, kissing her cheek as she sat on the edge of the bed, only for him to return home from work ten hours later to discover her still sitting there, Emily at a school friend’s and Jacob screaming in his cot.

Her mother had recognised her postnatal depression for what it was and done her best to help, encouraging her to get out more, to relax; she’d taken care of the children and sent Maddie to the hairdresser, for a massage, a girls’ night out. But months had oozed by, and she hadn’t got any better. In the end, her mother had forced her to see the doctor. For a long while, even Dr Calkins hadn’t been able to help and there had been frightening talk of inpatient care and electroconvulsive therapy. But finally, finally, just as Jacob reached his first birthday, the counselling and the pills had begun to work. Her feelings had gradually returned; mainly negative emotions to begin with, like hate and self-loathing and sadness, prickling sensations returning to a limb that had been numb for a long time. She’d been angry for quite a while, too, but everyone had been so glad to see her feel anything, they hadn’t minded. There had been tears, lots of tears, but eventually the good feelings had come back. Things had started to matter again. She started to care.

Through it all, Lucas had been steadfast in his support. Many men would have given up on her, but not Lucas. She liked to think of herself as independent and self-sufficient, but the truth was, she didn’t know what she’d have done without him.

His competence with the baby had surprised her. He’d been a hands-on stepfather with Emily from the very beginning, taking her to nursery school and teaching her to tie her own shoelaces. But Emily was a little girl; babies were a different kettle of fish. Lucas was so bookish and academic, Maddie hadn’t really expected him to get his hands dirty when Jacob was born. But he’d changed nappies and soothed tears, as if born to it. Even now, he was the one who comforted Jacob when he had toothache, sitting beside his cot and stroking his back for hours until he settled. On the nights Noah was truly inconsolable, it was Lucas who strapped him into the back of his car and drove around for hours until he fell asleep.