скачать книгу бесплатно

Sea People

Christina Thompson

‘Wonderfully researched and beautifully written’ Philip Hoare, author of Leviathan‘Succeeds in conjuring a lost world’ Dava Sobel, author of LongitudeFor more than a millennium, Polynesians have occupied the remotest islands in the Pacific Ocean, a vast triangle stretching from Hawaii to New Zealand to Easter Island. Until the arrival of European explorers they were the only people to have ever lived there. Both the most closely related and the most widely dispersed people in the world before the era of mass migration, Polynesians can trace their roots to a group of epic voyagers who ventured out into the unknown in one of the greatest adventures in human history.How did the earliest Polynesians find and colonise these far-flung islands? How did a people without writing or metal tools conquer the largest ocean in the world? This conundrum, which came to be known as the Problem of Polynesian Origins, emerged in the eighteenth century as one of the great geographical mysteries of mankind.For Christina Thompson, this mystery is personal: her Maori husband and their sons descend directly from these ancient navigators. In Sea People, Thompson explores the fascinating story of these ancestors, as well as those of the many sailors, linguists, archaeologists, folklorists, biologists and geographers who have puzzled over this history for three hundred years. A masterful mix of history, geography, anthropology, and the science of navigation, Sea People is a vivid tour of one of the most captivating regions in the world.

(#ulink_eabc739a-5ab0-5ef7-b8fb-5a3f3cedb1bf)

(#ulink_94fb0d84-b43d-52b9-b9c2-473ace1fc25f)

Copyright (#ulink_15e80482-6655-5756-9e3e-22da9f2a94e2)

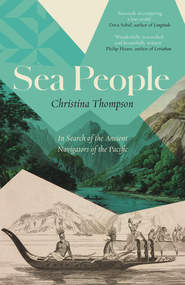

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://WilliamCollinsBooks.com) This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019 Copyright © Christina Thompson 2019 Cover photographs © Nuku Hiva pirogues, Marquesas Islands, Polynesia, engraving by Danvin and Boys / Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy / De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images; A View in Oheitepha Bay on the Island of Otaheite, from‘Captains Cook’s Last Voyage’, 1809 (coloured engraving), Webber, John (1750–93) (after) / Private Collection / Bridgeman Images Christina Thompson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Information on previously published material appears here (#litres_trial_promo). All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Source ISBN: 9780008339012 Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008339036 Version: 2019-02-15

Dedication (#ulink_9d3c3759-f60a-5251-bf97-6dff954a92a1)

For Tauwhitu

Epigraph (#ulink_0907e7f6-ada0-59a0-a076-ea6ffaff3ecb)

For we are dear to the immortal gods,

Living here, in the sea that rolls forever,

Distant from other lands and other men.

—Homer, the Odyssey

(translated by Robert Fitzgerald)

Contents

Cover (#ulink_8069d8b8-cdb1-5b23-a2e0-03f9994dc16f)

Title Page (#ulink_381f5ea0-7d91-5e98-8e92-f3d2c11fcae3)

Copyright (#ulink_0cf93bec-c184-5993-a97a-488f58ca2686)

Dedication (#ulink_9dc3fe42-2612-5f44-8d2a-e6a120778b71)

Epigraph (#ulink_9992c240-0468-595c-80dd-9e9c56f47ba8)

List of Illustrations (#ulink_ecfbda1c-ffd8-5245-9d33-cf8f39b66b32)

Prologue: Kealakekua Bay (#ulink_e0fb864d-dbc2-5a45-bcdc-e541db023fcd)

Part I: The Eyewitnesses (1521–1722) (#ulink_93591b5d-fb5b-5ecb-8750-f02db503b809)

In which we follow the trail of the earliest European explorers as they attempt to cross the Pacific for the first time, encountering a wide variety of islands and meeting some of the people who live there. (#ulink_93591b5d-fb5b-5ecb-8750-f02db503b809)

A Very Great Sea: The Discovery of Oceania (#ulink_18f00bd0-204c-5d5a-9ac3-bb607c0d7764)

First Contact: Mendaña in the Marquesas (#ulink_35a87658-d357-54bd-97ff-4735a5c4a8a7)

Barely an Island at All: Atolls of the Tuamotus (#ulink_c8e23911-d39b-5b5a-9cfe-f7cd541008ae)

Outer Limits: New Zealand and Easter Island (#ulink_91c493f7-5642-58b4-a645-d3cc31322552)

Part II: Connecting the Dots (1764–1778) (#ulink_142a7220-89d7-5990-94fe-106ce9f5e3dc)

In which we travel with Captain Cook to the heart of Polynesia, meet the Tahitian priest and navigator Tupaia, and sail with the two of them to New Zealand, where Tupaia makes an important discovery. (#ulink_142a7220-89d7-5990-94fe-106ce9f5e3dc)

Tahiti: The Heart of Polynesia (#ulink_df03caf7-4983-523a-840a-20737f90a827)

A Man of Knowledge: Cook Meets Tupaia (#ulink_32e108f0-9160-52e6-b531-62e6493388d7)

Tupaia’s Chart: Two Ways of Seeing (#litres_trial_promo)

An Aha Moment: A Tahitian in New Zealand (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III: Why Not Just Ask Them? (1778–1920) (#litres_trial_promo)

In which we look at some of the stories that Polynesians told about themselves and consider the difficulty nineteenth-century Europeans had trying to make sense of them. (#litres_trial_promo)

Drowned Continents and Other Theories: The Nineteenth-Century Pacific (#litres_trial_promo)

A World Without Writing: Polynesian Oral Traditions (#litres_trial_promo)

The Aryan Māori: An Unlikely Idea (#litres_trial_promo)

A Viking in Hawai‘i: Abraham Fornander (#litres_trial_promo)

Voyaging Stories: History and Myth (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV: The Rise of Science (1920–1959) (#litres_trial_promo)

In which anthropologists pick up the trail of the ancient Polynesians, bringing a new, quantitative approach to the questions of who, where, and when. (#litres_trial_promo)

Somatology: The Measure of Man (#litres_trial_promo)

A Māori Anthropologist: Te Rangi Hiroa (#litres_trial_promo)

The Moa Hunters: Stone and Bones (#litres_trial_promo)

Radiocarbon Dating: The Question of When (#litres_trial_promo)

The Lapita People: A Key Piece of the Puzzle (#litres_trial_promo)

Part V: Setting Sail (1947–1980) (#litres_trial_promo)

In which we set off on an entirely new tack, taking to the sea with a crew of experimental voyagers as they attempt to reenact the voyages of the ancient Polynesians. (#litres_trial_promo)

Kon-Tiki: Thor Heyerdahl’s Raft (#litres_trial_promo)

Drifting Not Sailing: Andrew Sharp (#litres_trial_promo)

The Non-Armchair Approach: David Lewis Experiments (#litres_trial_promo)

Hōkūle‘a: Sailing to Tahiti (#litres_trial_promo)

Reinventing Navigation: Nainoa Thompson (#litres_trial_promo)

Part VI: What We Know Now (1990–2018) (#litres_trial_promo)

In which we review some of the latest scientific findings and think about what it takes to answer big questions about the deep past. (#litres_trial_promo)

The Latest Science: DNA and Dates (#litres_trial_promo)

Coda: Two Ways of Knowing (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Illustration Section (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Christina Thompson (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations (#ulink_e43e9869-d9ad-5176-bff2-9b6c25740cd3)

1 “Map of the World (#litres_trial_promo), showing Terra Australis Incognita,” from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the first modern atlas, by Abraham Ortelius, 1570. Wikimedia Commons.

2 Tattooed Marquesan (#litres_trial_promo), “Back View of a younger inhabitant of Nukahiwa [Nuku Hiva], not yet completely tattooed,” in G. H. von Langsdorff, Voyage and Travels in Various Parts of the World (London, 1813). Courtesy Carol Ivy.

3 Easter Island moai (#litres_trial_promo), “A View of the Monuments of Easter Island,” by William Hodges, ca. 1776. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Wikimedia Commons.

4 Nukutavake canoe (#litres_trial_promo), acquired in the Tuamotus in 1767 by Captain Samuel Wallis of H.M.S. Dolphin. British Museum.

5 Nukutavake canoe detail (#litres_trial_promo) showing repair.

6 Portrait of Captain (#litres_trial_promo) James Cook by William Hodges, 1775–76. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

7 Drawing by Tupaia (#litres_trial_promo) of a Māori trading crayfish with Joseph Banks, 1769. British Library.

8 Peter Henry Buck (#litres_trial_promo) (Te Rangi Hiroa) in academic robes, ca. 1904. Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand.

9 Felix von Luschan’s (#litres_trial_promo) Hautfarbentafel (skin color panel). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

10 Richard Owen (#litres_trial_promo) standing beside Dinornis novaezealandiae (large species of moa) while holding the bone fragment he was given in 1839. From Richard Owen, Memoirs on the extinct wingless birds of New Zealand (London, 1879). Wikimedia Commons.

11 Moa egg found by Jim Eyles at Wairau Bar in 1939 (#litres_trial_promo). Photograph by Norman Heke, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

12 Necklace of moa bone reels and stone (#litres_trial_promo) “whale tooth” pendant, discovered at Wairau Bar. Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand.

13 “The Arrival of the Maoris (#litres_trial_promo) in New Zealand” by Louis John Steele and Charles F. Goldie (1898), Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the late George and Helen Boyd, 1899. Based on Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), this painting depicts a vision of Polynesian voyaging not unlike that implied by drift voyaging theories.

14 Reconstructed (#litres_trial_promo) three-thousand-year-old Lapita pot from Teouma, Efate Island, Vanuatu. Photograph by Philippe Metois, courtesy Stuart Bedford and Matthew Spriggs.

15 Micronesian stick chart (#litres_trial_promo) from the Marshall Islands. Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

16 Hōkūle‘a passing the Statue of Liberty in 2016 (#litres_trial_promo) on the Mālama Honua voyage around the world. Photo by Na‘alehu Anthony, courtesy ‘Ōiwi TV and the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Prologue (#ulink_54ac68a0-e959-54ea-8f2d-fcb38171a793)

Kealakekua Bay (#ulink_54ac68a0-e959-54ea-8f2d-fcb38171a793)

Map of the Sandwich Islands by Giovanni Cassini (Rome, 1798), based on Cook’s chart of Hawai‘i.

STORY OF HAWAII MUSEUM, KAHULUI, MAUI.

KEALAKEKUA BAY LIES on the west, or leeward, side of the Big Island of Hawai‘i, in the rain shadow cast by the great volcano Mauna Loa. It is a smallish bay about a mile wide, open to the southwest, with a bit of flat land at either end and a great wall of cliffs along the middle, where in ancient times the bodies of Hawaiian chiefs were hidden in secret caves. The name of the bay, Kealakekua, means in Hawaiian “the Path of the God,” and in the final centuries of Polynesian isolation, before the arrival of Europeans, it was a seat of power and the ancestral home of no less a personage than the first Hawaiian monarch, Kamehameha I.

To get to Kealakekua Bay, you take the main road south from Kailua, leaving behind the more heavily settled areas of the Kona Coast and passing through a series of small towns. The highway on this part of the island runs along the shoulder of the mountain, and the drive down to sea level is a steep one. Turning off at the Napo‘opo‘o Road, you wind down through an arid landscape of mesquite and lead trees interspersed with ornamental plantings of hibiscus and plumeria. Taking a right at the bottom and following the road to its end, you come at last to a little cul-de-sac under a pair of spreading jacarandas. The beach, with its jumble of boulders, is a stone’s throw away, the high red rampart of the Pali looms on the right, and, squinting into the distance, you can just make out the low, scrubby outline of the farther shore.

Immediately adjacent rises the wall of the Hikiau Heiau, a large rectangular platform neatly built of close-fitting lava stones. The first time we visited this spot, my husband, Seven, and I were at the end of a long trip across the Pacific with our three sons. We had seen these sorts of structures before, coming upon them half-hidden in the forests of Nuku Hiva and high on a headland on O‘ahu’s North Shore, and once on a beach like this on the island of Ra‘iatea. In many parts of Polynesia they are known as marae, and in the days before Europeans reached the Pacific they were places of great mystery and supernatural power. Presided over by chiefs and priests and dedicated to particular gods, they were sites of sacrifice—including, occasionally, of humans—and propitiation to ensure safe voyaging or good health or plentiful food or success in war. They were decorated with scaffoldings and carved wooden images, and often with skulls, and were governed by the incontestable law of kapu (known elsewhere as tapu and the source of our word “taboo”), the system of rules and prohibitions linking everyday existence to the world of the numinous, which permeated every aspect of ancient Polynesian life.

We picked our way around the outside of the heiau, trying to get a sense of what was there. What remained of the original structure was a raised dry-stone platform more than a hundred feet long and about half as wide, rising to a height of ten feet at the beach end. It was said to have been nearly twice this size when it was first seen by Europeans, in the late 1700s, and would have been an imposing edifice with a commanding view of the bay. Or so we imagined. The stone stairway up to the top of the platform was roped off, and no fewer than three separate signs reminded us that no trespassing was allowed. Visitors were admonished not to wrap or to remove any of the stones or to climb on the walls or in any other way to disrespect the site. Heiau on the islands of Hawai‘i have more signage than similar structures on other islands, and, given the number of visitors, it’s easy to see why. But encounters with the past are different when they are mediated in this way, and I was glad that our first experience of such places had been deep in a forest in the Marquesas, where we had wandered freely among the ruins, ruminating after our own fashion upon the passage of time.

Directly in front of the heiau was an obelisk built of the same black lava rock but cemented in a very un-Polynesian way. It was about ten or twelve feet high and was mounted with a bronze commemorative plaque that read:

In this heiau, January 28, 1779,

Captain James Cook R. N.

read the English burial service

over William Whatman, seaman,

the first recorded Christian service

in the Hawaiian Islands.

Here was a completely different story from the one the heiau had to tell. On the surface, it was the story of poor Whatman, dead of a stroke, whose last wish had been to be buried on shore, and of the almost accidental arrival of Christianity, the rippling effect of which would be felt in these islands for centuries to come. But the much larger story, only obliquely indicated here, was of the coming of Europeans to the Pacific—the most consequential thing to have happened in these islands since the arrival of the Polynesians themselves. And so, while we might have come simply to see the heiau, with its tantalizing glimpse of a remote and cryptic Polynesian past, it was, in fact, the intersection of these two histories that had brought us to Kealakekua Bay.