скачать книгу бесплатно

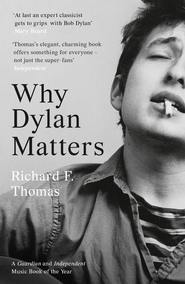

Why Dylan Matters

Richard F. Thomas

‘At last an expert classicist gets to grips with Bob Dylan’ Mary BeardWhen the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Bob Dylan in 2016, the literary world was up in arms. How could the world’s most prestigious book prize be awarded to a famously cantankerous singer-songwriter in his seventies, who wouldn’t even deign to make a victory speech?In Why Dylan Matters, Harvard Professor Richard F. Thomas answers that question with magisterial erudition. A world expert on Classical poetry, Thomas was initially ridiculed by his colleagues for teaching a course on Bob Dylan alongside his traditional seminars on Homer, Virgil and Ovid. Dylan’s Nobel prize win brought him vindication, and he immediately found himself thrust into the limelight as a leading academic voice in all matters Dylanological.This witty, personal volume is a distillation of Thomas’s famous course, and makes a compelling case for moving Dylan out of the rock n’ roll Hall of Fame and into the pantheon of Classical poets. The most dazzlingly original and compelling Dylan book in decades, Why Dylan Matters will amaze and astound everyone from the first-time listener to the lifetime fan. You’ll never think about Bob Dylan in the same way again.

(#ulink_bd437b9f-cd44-5faf-a2de-735805bd7cff)

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_26a9099c-93c6-5716-82f4-ef3c26d801e1)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

First published in the United States by Dey Street, an imprint of William Morrow in 2017

This William Collins ebook edition published in 2018

Copyright © Richard F. Thomas 2017

Designed by Renata De Oliveira

Richard F. Thomas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Nobel Prize in Literature, Award Ceremony Speech 2016 © The Nobel Foundation 2016

Nobel Prize in Literature, Banquet Speech 2016 © The Nobel Foundation 2016

Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Lecture 2017 © Bob Dylan p. 13, Nobel Prize in Literature, Medal image, reverse side © The Nobel Foundation, Photo: Lovisa Engblom

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008245467

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008245481

Version: 2018-11-06

A GUARDIAN AND INDEPENDENT BEST MUSIC BOOK OF 2017 (#ulink_f407bb0d-776c-542d-af08-34442162e01d)

‘At last an expert classicist gets to grips with Bob Dylan. Richard Thomas takes us from Dylan’s high school Latin club to his haunting engagement with Ovid and Homer in recent albums. He carefully argues that Dylan’s poetry deserves comparison with Virgil’s – and Thomas, senior professor of Latin at Harvard and author of some of the most influential modern studies of Virgil, should know!’

Mary Beard

‘A poignant blend of memoir, literary analysis through a classical lens, musicology and, above all, love. [Thomas] loves Dylan with a passion so selfless and so intense that it’s impossible to emerge from the book untouched’

Guardian

‘Accessible and enjoyable … Richard F. Thomas’s elegant, charming book offers something for everyone – not just the super-fans’

Independent

‘The coolest class on campus’

New York Times

‘The book joyously bounces from topic to topic, mixing anecdotes about Dylan’s creative process, historical concerts, and wry press conferences with penetrating literary critique – and no shortage of Thomas’ own personal recollections of bonding with Dylan’s music. A highly informed, yet intimately personal celebration of one of our most important living writers – not despite, but because of the medium in which he writes’

NPR

‘Thomas’ outstanding, eminently readable and beautifully bound work, answers that question in relation to his subject with a resounding ‘Yes’. Dylan matters. Emphatically’

Tribune

‘Why Dylan Matters is about the work of an astonishingly great artist and performer, and how that work echoes the great Greek and Roman poet-performers – Homer, Virgil, Horace, Catullus and Ovid – whose five voices are heard in Dylan’s work. Richard Thomas teaches us, with loving and passionate authority, how he hears in these poems the voices and music of these great ancient poets; he teaches us how poems listen and hear and speak to other poems through all time’

David Ferry, winner of the National Book Award for Poetry

‘Richard Thomas has created a monument to Bob Dylan – and, also, a Rosetta Stone. The erudite and politically engaged Thomas is the perfect guide through the wondrous mystery of Dylan’s genius’

James Carroll, author of Constantine’s Sword

‘Secures Dylan’s place in a pantheon of literary heroes from Virgil to Eliot. A critical breakthrough that makes a masterful case for why Dylan is the bard of our times’

Andrew McCarron,

author of Light Come Shining: The Transformations of Bob Dylan

‘Listen to Bob Dylan in performance. But read this book for help on how to hear his lyrics’

Irish Examiner

‘An enormously rewarding academic study of Dylan’s significance and significations … Thomas’s classicist’s training, sharp ear for allusion and taste for detailed research give his book a very special and distinctive allure’

Argo

DEDICATION (#ulink_68e0dc1a-549f-5345-b258-75326c9d2822)

To four generations of Harvard freshman in

“FRSEM 37u: Bob Dylan”

2004–2016

CONTENTS

COVER (#uce59473f-87eb-53d5-a2a7-069cf54b5197)

TITLE PAGE (#u401c0b2d-6874-55d9-adfb-da28f49f2f8c)

COPYRIGHT (#ud9bafcf6-8d39-5e1f-a7c6-cdd5a2f0fee4)

PRAISE (#ufaf5824b-aeb6-5e6f-a7bd-6474c0a4f284)

DEDICATION (#uf88ba3a4-1dac-506b-9871-a44865224ac5)

BOB DYLAN’S DISCOGRAPHY (#u1a82fce7-763e-5a7e-b31a-23ad2cb95d2c)

1 WHY DOES DYLAN MATTER TO US? (#udd7df952-a08c-5e36-8c25-c1bb7583ff75)

2 TOGETHER THROUGH LIFE (#u27ce8c8b-92f0-57ec-90ea-1c75927de94b)

3 DYLAN AND ANCIENT ROME: “THAT’S WHERE I WAS BORN” (#uab5b31c4-9569-51fd-9685-2956cb897488)

4 “VIBRATIONS IN THE UNIVERSE”: DYLAN TELLS HIS OWN STORY (#litres_trial_promo)

5 THE EARLY THEFTS: “MINE’VE BEEN LIKE VERLAINE’S AND RIMBAUD’S” (#litres_trial_promo)

6 “THE GIFT WAS GIVEN BACK”: TIME OUT OF MIND AND BEYOND (#litres_trial_promo)

7 MATURE POETS STEAL: VIRGIL, DYLAN, AND THE MAKING OF A CLASSIC (#litres_trial_promo)

8 MODERN TIMES AND THE WORLD’S ANCIENT LIGHT: BECOMING HOMER (#litres_trial_promo)

9 THE SHOW’S THE THING: DYLAN IN PERFORMANCE (#litres_trial_promo)

CONCLUSION: SPEECHLESS IN STOCKHOLM (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB DYLAN LYRICS—COPYRIGHT INFORMATION (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB DYLAN’S DISCOGRAPHY (#ulink_a60ec092-e7d8-5826-9ecf-2b6d34572a66)

1 (#ulink_1ea2b778-0197-56bc-b6f6-b20f0a7b5c48)

WHY DOES DYLAN MATTER TO US? (#ulink_1ea2b778-0197-56bc-b6f6-b20f0a7b5c48)

THERE’S A MOMENT WHEN ALL OLD THINGS

BECOME NEW AGAIN

—BOB DYLAN

Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde was one of two albums I packed in the trunk I sent from New Zealand to Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the early summer of 1974. The other was Songs of Leonard Cohen. I was twenty-three years old and had sold off the rest of my record collection to finance a two-month backpacking trip through Greece, before starting my doctoral studies at the University of Michigan. The trip to Greece was my first, but I had been fascinated by the Greeks and Romans since the age of nine, growing up in Auckland, New Zealand, half a world away from where their civilizations rose and fell. I arrived in Ann Arbor on August 18, 1974, days after Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency, ready to begin my professional life as a scholar and teacher of classical literature. My trunk finally arrived in October, and its familiar contents were a welcome sight. Along with the survivors of my record collection, that trunk contained the few classical texts I had accumulated as an undergraduate: the writings of Homer and Virgil, the epic poets of Greece and Rome, along with Sappho, Catullus, Horace, and Ovid, the brilliant lyric poets and love poets whose work captures what it means to live and love, to win and lose, to grieve and celebrate, and to grow old and die. For two thousand years, their poetry has fired the minds and imaginations of philosophers and poets, painters, sculptors and musicians, dreamers and lovers.

For the past forty years, as a classics professor, I have been living in the worlds of the Greek and Roman poets, reading them, writing about them, and teaching them to students in their original languages and in English translation. I have for even longer been living in the world of Bob Dylan’s songs, and in my mind Dylan long ago joined the company of those ancient poets. He is part of that classical stream whose spring starts out in Greece and Rome and flows on down through the years, remaining relevant today, and incapable of being contained by time or place. That’s why Dylan matters to me, and that’s what this book is about.

From the beginning of his musical career, Bob Dylan has been working with artistic principles, and attitudes toward composition, revision, and performance, that bear many similarities to those of the ancients. He has also been living and writing in a world that bears many striking similarities to that of the ancient Romans, whose republic was the model on which the Founding Fathers built our own system. I believe that Dylan early on came to recognize this similarity, and it has been reflected in the worlds he creates for us in his music ever since.

Cullen Murphy’s 2007 book, Are We Rome?, addresses this question, arguing that our time (Dylan’s time) looks quite a bit like for the most part that of the Romans at various moments in their more than thousand-year history. According to Cullen, the ties that bind the two cultures include the condition of being a superpower, tensions caused by ethnic differences, the persistent memory of civil wars long after the last battle was fought, a sense of the fragility of political structures and decline of the human condition, the relaxation of moral and religious bonds, and a pushback against the countercultures.

At the heart of it, Rome around the last century BC and the beginnings of the first century AD and America in the second half of the twentieth share a sense of modernity, by which I mean a few things. By then Rome had more or less established herself as the dominant power in the Mediterranean world. The absence of serious external enemies, along with the sheer size of her empire, led to competing struggles among those whose task it was to govern the state and extend and defend its vast borders. Starting in the middle of the century these competing forces clashed, and a series of civil wars led to the elimination—by death on the battlefield, murder, and assassination—of one figure after another, along with the defeat of the ideals or interests they represented. The names are well known: Pompey the Great, Julius Caesar, Brutus, Mark Antony, all killed in a succession of bloody civil wars that went on for eighteen years. By around 30 BC, Augustus Caesar as he would be renamed, the last man standing, delivered the final blow to the republic and stepped in as the first emperor of Rome.

This period of political uncertainty coincided with the emergence of a brilliant succession of poets and other writers, as happens at moments of political and national crisis or greatness: Athens in the fifth century BC, Elizabethan England, America and Great Britain between the two world wars—the rise of the so-called Moderns. Such moments give rise to a heightened sense of the past, along with uncertainties about the future. In each of these periods new art forms responded to what was happening, disrupting the old forms and traditions, busting them up, renewing what had gone before, moving into uncharted territory. The Roman poets in question will become familiar in the pages that follow: Catullus, Virgil, Horace, and Ovid. Others would have filled out their ranks, but their texts did not survive the centuries. Their art addressed the large issues of their day, the perilous state of their world, and the aftermath of civil war. Similarly, Dylan’s art would speak to the horrors of the wars of his day, the Second World War and the cold war that followed, historic episodes like the Cuban missile crisis, and the fear of nuclear warfare, eventually Vietnam, even Iraq. And in both cases, through music and poetry that would prove to be enduring, memorable, and meaningful to ages beyond their own, Dylan and the ancients explore the essential question of what it means to be human.

Dylan’s songs have been part of my song memory since my mid-teens, but it would be decades before they became more fully aligned in my mind with the Greek and Roman poets I was beginning to read back then. And it was chiefly in the twenty-first century that Dylan started to reference, borrow from, and “creatively reuse” their work in his own songs. I first began to make the connection after a trip to the coast of Normandy, where I had been invited in the spring of 2001 to give a lecture at the University of Caen on Virgil and other Roman poets. My host, Catharine Mason, a linguistics professor there, met me at the train station. She suggested that instead of touring the town, pretty much pummeled out of its historical state before the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944, we might head for the beach. That sounded good to me, so I followed her to the parking lot. As we got into her car and she turned the key in the ignition, music came blasting from her car stereo. As we’ve all done, she had gotten out of the car earlier without thinking to turn down the volume, and the familiar bars of Dylan’s “Idiot Wind,” then and now one of my favorite songs, urgently interrupted our tentative conversation:

You hurt the ones that I love best and cover up the truth with lies

One day you’ll be in the ditch, flies buzzin’ around your eyes

Blood on your saddle

Our conversation quickly turned to Dylan, to that song and its importance. For Catharine, a single mother who had recently gone through a divorce, and an American expatriate bringing up two young sons in France, the breakup song had powerful personal resonance. She had gotten hooked on Dylan twenty-five years after I had, with his 1990 album Under the Red Sky, whose nursery rhyme and fairy-tale traditions became part of the rhythm of bringing up her two young sons. As we walked on what had been Sword Beach, landing point for the British Third Division on D-Day, she talked about her plans for a conference on the performance art of Dylan. Did I want to give a paper at her conference, and maybe even co-edit the proceedings into a volume, she asked? I said sure, not really knowing how I would find a way into the topic. But in the back of my mind, I was thinking about how the songs from Dylan’s 1997 album, Time Out of Mind, had lately begun somehow to remind me of the work of the Roman poets. Still, I had yet to share this insight with anyone.

It was not until many months after my trip to Caen, soon after September 11, 2001, the day that permanently changed the modern world, that what I would present at the Dylan conference became clear to me. Dylan’s album “Love and Theft” came out on that day, and I bought it at the Tower Records in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a daze, in the hours after the towers in New York had been leveled. When I eventually listened to the album, I heard Virgil, loud and clear in the tenth verse of “Lonesome Day Blues”:

I’m gonna spare the defeated—I’m gonna speak to the crowd

I’m gonna spare the defeated, boys, I’m gonna speak to the crowd

I’m goin’ to teach peace to the conquered

I’m gonna tame the proud.

The idiom, rhymes, and music of these lines belonged to Dylan, but the thought and diction, rearranged by Dylan, came from Rome’s greatest poet, Virgil. In Dylan’s lyrics, I recognized these lines from Virgil’s Aeneid, spoken by Anchises, father of Aeneas, the mythical founder of Rome. Anchises, who had died on the journey from Troy to Sicily, instructs his son from the Underworld on just how Rome is to rule the world:

but yours will be the rulership of nations,

remember, Roman, these will be your arts:

to teach the ways of peace to those you conquer,

to spare defeated peoples, tame the proud.