Полная версия:

The Times Great Lives

GREAT LIVES

GREAT LIVES

a century in obituaries

Edited by Anna Temkin

Times Books

Published by Times Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Ebook first edition 2015

© Times Newspapers Ltd 2015

www.thetimes.co.uk

Ebook Edition © September 2015 ISBN: 978-0-00-816480-5, version 2015-08-18

The Times is a registered trademark of Times Newspapers Ltd

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

The contents of this publication are believed correct. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

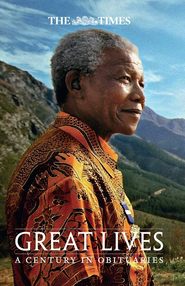

Cover Image © Louise Gubb

Title

Copyright

Introduction

Abridged Introduction

Contents

Lord Kitchener

V. I. Lenin

Giacomo Puccini

Claude Monet

Emmeline Pankhurst

D. H. Lawrence

Dame Nellie Melba

Sir Edward Elgar

Marie Curie

Sigmund Freud

Amy Johnson

Virginia Woolf

David Lloyd George

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Adolf Hitler

General G. S. Patton

John Maynard Keynes

Henry Ford

Mahatma Gandhi

George Orwell

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Arnold Schoenberg

Joseph Stalin

Alan Turing

Henri Matisse

Sir Alexander Fleming

Albert Einstein

Humphrey Bogart

Arturo Toscanini

Christian Dior

Dorothy L. Sayers

Frank Lloyd Wright

Aneurin Bevan

Ernest Hemingway

Marilyn Monroe

President John F. Kennedy

Lord Beaverbrook

Ian Fleming

T. S. Eliot

Sir Winston Churchill

Le Corbusier

Yuri Gagarin

Martin Luther King

Enid Blyton

Bertrand Russell

Jimi Hendrix

President Gamal Abdel Nasser

Coco Chanel

Igor Stravinsky

Louis Armstrong

Duke of Windsor

Sir Noel Coward

Pablo Picasso

Charles Lindbergh

P. G. Wodehouse

Dame Agatha Christie

Field Marshal Montgomery

Mao Tse-tung

Benjamin Britten

Elvis Presley

Maria Callas

Charlie Chaplin

Jesse Owens

Jean-Paul Sartre

Sir Alfred Hitchcock

Mae West

John Lennon

Bob Marley

Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader

Orson Welles

Henry Moore

Andy Warhol

Jacqueline du Pré

Sir Frederick Ashton

Sugar Ray Robinson

Ayatollah Khomeini

Laurence Olivier

Dame Margot Fonteyn

Miles Davis

Menachem Begin

Francis Bacon

Elizabeth David

Willy Brandt

Rudolf Nureyev

Richard Nixon

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Fred Perry

Harold Wilson

Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Diana, Princess of Wales

Mother Teresa

Frank Sinatra

Iris Murdoch

Stanley Kubrick

Yehudi Menuhin

Sir Alf Ramsey

Raisa Gorbachev

Sir Stanley Matthews

Dame Barbara Cartland

Sir John Gielgud

Sir Alec Guinness

Don Bradman

Christiaan Barnard

Spike Milligan

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Ronald Reagan

Francis Crick

Pope John Paul II

Rosa Parks

Luciano Pavarotti

Sir Edmund Hillary

Michael Jackson

Elizabeth Taylor

Steve Jobs

Sir Bernard Lovell

Neil Armstrong

Baroness Thatcher

Seamus Heaney

Sir David Frost

Nelson Mandela

Lady Soames

Lord Attenborough

Sir Terry Pratchett

Lee Kuan Yew

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Publisher

Introduction

Anna Temkin

Assistant Obituaries Editor, The Times

Perhaps the most effective way to study history is to read the obituaries of those who have shaped it. Many would agree there is no better place to do so than in the pages of The Times. Its notices have long been a prime source for scholars; to this day, contributors to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography are invariably advised to start their research by consulting the relevant Times obituary.

The pieces chronologically assembled here, from Lord Kitchener to Lee Kuan Yew, form an enthralling snapshot of the past 100 years. Over that period The Times house style has of course changed – to include details of survivors, for example, and a final paragraph recording the date of birth and date of death. The comprehensive first edition of Great Lives, edited by Ian Brunskill, was published in 2005 and closed with the obituary of Pope John Paul II. In the ten years since, great lives have continued to be recorded in The Times. Many of these would be worthy of appearing in this second edition and the selection process has necessarily involved making invidious choices. Who to include and who to exclude, while still giving due coverage to the worlds of entertainment, sport et al? Apart from the two most high profile deaths in recent years – those of Baroness Thatcher and Nelson Mandela – the new contenders were generally open to debate. Choosing which to add and which, very reluctantly, to remove meant avoiding a number of risks: too many politicians (farewell Earl Attlee), too few writers (stay put Enid Blyton), too much music (so long Glenn Gould), not enough science (welcome Sir Bernard Lovell). All these were important considerations when updating this edition.

Rosa Parks, who died in 2007, was at the forefront of the civil rights movement and, appropriately, is now among the vanguard of the new obituaries in this compendium. Between the Iron Lady and South Africa’s much-loved ‘Madiba’, the world also lost Seamus Heaney, whose poetry caused nothing short of a literary sensation, and the doyen of television interrogators Sir David Frost, who famously teased a confession out of President Nixon over Watergate. Sir Edmund Hillary modestly described his life as merely a ‘constant battle against boredom’ but Britain held its breath as he became the first climber to reach the summit of Everest. Again, how could anyone forget the visionary Steve Jobs whose name will forever be synonymous with the ubiquitous Apple?

The perennial power of the obituary is that it brings the dead to life. At its most compelling, it combines biography and historical context with anecdotes and telling quotations; such is the art of the skilled obituarist. The majority of Times notices are written in house, but when necessary the paper avails itself of specialist knowledge from outsiders. All, however, are unsigned. This policy of anonymity ultimately allows for a fairer, fuller account of the subject’s life and the obituarist need not fear any backlash following publication. After Nubar Gulbenkian, the Armenian business magnate, was embroiled in a bitter feud with his father, a famous oil millionaire, he was concerned which side of the dispute his obituary in The Times would take. He therefore invited members of the paper’s staff for lunch at the Ritz, offering them £1000 for a view of his draft obituary. He never saw it and when the notice actually appeared in 1972, it gave a balanced portrayal of the family feud. That kind of proportional representation, as it were, is exemplified in many of the pieces reproduced here. Michael Jackson’s obituary, for instance, acknowledges his reputation as the king of pop while also addressing the sensational allegations of impropriety levelled at him.

These pages contain some of the most extraordinary lives that have defined the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries; within them are stories of genius, innovation, adversity and, at times, sheer eccentricity. Thomas Carlyle declared, ‘History is the essence of innumerable biographies’. His ‘Great Man’ theory that the past can be explained by the influence of leaders and heroes may not be infallible (after all, some of the most significant could not be regarded as either noble or heroic). Yet there is no doubt that all the men and women of this collection left an indelible mark on both the world they knew and the one that we now inhabit. Their obituaries have stood the test of time and are, in that sense, a fitting reflection of The Times itself.

Abridged Introduction

to the First Edition

Ian Brunskill

Former Obituaries Editor, The Times

From its beginnings in 1785 The Times has recorded significant deaths. Often in the early days this amounted to little more than a list of names of people who had died, and on more than one occasion The Times simply plagiarized a notice from another paper if it had none of its own. It was under John Thadeus Delane, Editor of The Times from 1841 to 1877, that this began to change. Delane clearly recognized that the death of a leading figure on the national stage was an event that would seize the public imagination as almost nothing else could, and that it demanded more than just a brief notice recording the demise. ‘Wellington’s death,’ Delane told a colleague, ‘will be the only topic’.

Delane instituted the practice of preparing detailed, authoritative – and often very long – obituaries of the more important and influential personalities of the day while they were still alive. The resulting increase in the quality and scope of the major notices ensured that, even if the paper’s day-to-day obituary coverage remained erratic, The Times in the second half of the 19th century rose to the big occasion far better than its rivals could. The investment of effort and resources was not hard to justify. The Times obituaries not only found a ready following among readers of the paper but were soon being collected and republished in book form too. Six volumes of ‘Biographies of Eminent Persons’ covered the period 1870-1894.

It was not until 1920, however, that The Times appointed its first obituary editor, and it was some years later still before the paper began to run a daily obituary page. As late as 1956, the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis could complain in a letter to the retired Eton schoolmaster George Lyttelton: ‘The obituary arrangements at The Times are haphazard and unsatisfactory. The smallest civil servant – Sewage Disposal Officer in Uppingham – automatically has at least half a column about him in standing type at the office, but writers and artists are not provided for until they are eighty.’

That was a little unfair, even at the time, but if matters have improved since then, it is in large part due to the efforts of the late Colin Watson, who took over as obituaries editor in the year Hart-Davis expressed that disparaging view and who remained in the post for 25 years. He built up and maintained the stock of advance notices so that there were usually about 5,000 on file at any one time, a figure that has remained more or less constant ever since.

Watson, in an article written on his retirement, gave a revealing and only half-frivolous account of what the whole business involves. It was – is – a relentless, if rewarding, task: ‘You may read and read and read,’ he wrote, ‘particularly history; turn on the radio; listen for rumours of ill-health (never laugh at so much as a chesty cold); and you may write endless letters – but never dare say you are on top.’

If Watson may in many respects be said to have brought the obituary department into the modern world, it fell to his successors, particularly John Higgins and Anthony Howard, to show how effectively the paper could respond when other newspapers, from the mid-1980s, began to expand their obituary coverage to match that of The Times. There were some elsewhere who claimed, in the course of this expansion, to have invented or reinvented the newspaper obituary in its modern form – chiefly, it often seemed, by treating all their subjects like amusing minor characters in the novels of Anthony Powell. In fact, as I hope this collection shows, the obituary form as practised for more than a century in The Times had at its best always been both broader in range and livelier in approach than may generally have been assumed.

Lord Kitchener

5 June 1916

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was born at Gunsborough House, near Listowel, in County Kerry, on June 24, 1850. He was the second son of Lieutenant-Colonel H. H. Kitchener, of Cossington, Leicestershire, by his marriage with Frances, daughter of the Rev. John Chevallier, dd, of Aspall Hall, Suffolk, and was therefore of English descent though born in Ireland.

He was educated privately by tutors until the age of 13, when he was sent with his three brothers to Villeneuve, on the Lake of Geneva, where he was in the charge of the Rev. J. Bennett. From Villeneuve, after some further travels abroad, he returned to London, and was prepared for the Army by the Rev. George Frost of Kensington Square. He entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1868 and obtained a commission in the Royal Engineers in January, 1871. During the short interval between passing out of Woolwich and joining the Engineers he was on a visit to his father at Dinan, and volunteered for service with the French Army. He served under Chanzy for a short time, but was struck down by pneumonia and invalided home. He now applied himself vigorously to the technical work of his branch, and laboured incessantly at Chatham and Aldershot to succeed in his profession.

Palestine and Cyprus

His first chance of adventure arose owing to a vacancy on the staff of the Palestine Exploration Society. Kitchener was offered the post in 1874 and at once accepted it. He remained in the Holy Land until the year 1878, engaged first as assistant to Lieutenant Conder, re, in mapping 1,600 square miles of Judah and Philistia, and then in sole charge during the year 1877 surveying that part of Western Palestine which still remained unmapped. The work was done with the thoroughness which distinguished Kitchener’s methods in his subsequent career. He rejoined Conder in London in January, 1878, and by the following September the scheme of the Society was carried through, and a map of Western Palestine on a scale of one inch to a mile was satisfactorily completed. The work entailed considerable hardship, and even danger. Kitchener suffered from sun-stroke and fever. He and his surveying parties were frequently attacked by bands of marauders, and on one of these occasions both Conder and he barely escaped with their lives. On another occasion Kitchener pluckily rescued his comrade from drowning. His survey work in Palestine led directly to his nomination for similar work in Cyprus, where he began the map of the island which was eventually published in 1885.

Egypt and the Red Sea

Realising that trouble was brewing in Egypt, Kitchener managed to be at Alexandria on leave at the time of Arabi’s revolt. He served through the campaign of 1882, and, thanks largely to his knowledge of Arabic, became second in command of the Egyptian Cavalry when Sir Evelyn Wood was made Sirdar of the Egyptian Army. He left Suez in November, 1883, to take part in the survey of the Sinai Peninsula, but almost immediately returned for service in the Intelligence branch. He was sent southward after the defeat of Hicks Pasha in order to win over the tribes and prevent the further spread of disaffection. His personality and influence did much. The Mudir of Dongola in response to Kitchener’s appeal, fell upon the dervishes at Korti and defeated them. But the tide of Mahdi-ism was still flowing strongly. By July, 1884, Khartum was invested, and upon Kitchener fell the duty of keeping touch between Gordon and the expedition all too tardily dispatched for his relief.

Kitchener was now a major and daa and qmc on the Intelligence Staff. In December, 1884, Wolseley and his troops reached Korti. Kitchener accompanied Sir Herbert Stewart’s column on its march to Metemmeh, but only as far as Gakdul Wells, and consequently he was not at Abu Klea. When the expedition recoiled, it became Kitchener’s painful duty to piece together an account of the storming of Khartum and the death of Gordon. For Kitchener’s services in this arduous and disappointing campaign there came a mention in dispatches, a medal and clasp, and the Khedive’s star. In June, 1885, he was promoted lieutenant-colonel. In the summer the Mahdi died and the Khalifa Abdullahi succeeded him. Kitchener had resigned his commission in the Egyptian Army and had returned to England, but he was almost at once sent off to Zanzibar on a boundary commission and was subsequently appointed Governor-General of the Red Sea littoral and Commandant at Suakin in August, 1886. Here he soon found himself at grips with the famous Emir Osman Digna.

After some desultory fighting round Suakin Kitchener marched out one morning, surprised Osman’s camp at Handont, and carried it with the Sudanese. But in the course of the action he was severely wounded by a bullet in the neck, and was subsequently invalided home. The bullet caused him serious inconvenience until it was at last extracted. In June, 1888, he became colonel and adc to her Majesty Queen Victoria, who had formed a high and just estimate of Kitchener’s talents and ever displayed towards him a gracious regard. He rejoined the Egyptian Army as Adjutant-General, and was in command of a brigade of Sudanese when Sir Francis Grenfell stormed Osman Digna’s line at Gemaizeh. Toski, in the following summer, was another success, and Kitchener’s share in it at the head of 1,500 mounted troops won for him a cb.

Three less eventful years now went by while the Egyptian Army, encouraged by its successes in the Geld, grew in strength and efficiency. In 1892 Kitchener succeeded Grenfell as Sirdar, and in 1894 was made a kcmg.

The Reconquest of the Sudan

Lord Salisbury’s Government decided on March 12, 1896, that the time had come for a forward movement on the Nile. Their immediate object was to make a diversion in favour of Italy, whose troops had just been totally defeated by the Abyssinians at Adowa, but the natural impetus of the advance carried the Sirdar and his army eventually to Khartum. Kitchener was ready when the order to advance was given. He had 10,000 men on the frontier, rails ready to follow them to Kerma, and all preparations made for supply. At Firket he surprised the dervishes at dawn, and at a cost of only 100 casualties caused the enemy a loss of 800 dead and 1,000 prisoners. A period of unavoidable inactivity ensued to admit of the construction of the railway, the accumulation of supplies, and the preparation of a fleet of steamers to accompany the advance. Cholera ravaged the camp and sandstorms of a furious character impeded operations, but the advance was at last resumed, and after sharp fights at Hafir and Dongola, the latter town was occupied on September 23, and the first stage of the reconquest of the Sudan was at an end. Kitchener was promoted major-general, with a very good, but not yet assured, prospect of completing the work which he had begun so well.

From the various lines of further advance open to him Kitchener chose the direct line from Wady Halfa to Abu Hamed, and formed the audacious project of spanning this arid and apparently waterless desert, 230 miles broad, with a railway, as he advanced. The first rails of this line were laid in January, 1897, and 130 miles were completed by July. Abu Hamed was captured on August 7 by Hunter with a flying column from Merowi, and Berber on August 31. The remaining 100 miles of the desert railway were then completed. Fortune favoured Kitchener at this period. Water was found by boring in the desert, but the construction of the line was still a triumph of imagination and resource. There were risks in the general situation at this moment, for the position of the army was temporarily far from favourable. There was a specially difficult period towards the close of 1897, when large dervish forces were massed at Metemmeh and a dash to the north seemed on the cards. But the Khalifa delayed his stroke, and when in February, 1898, the Khalifa’s lieutenant Mahmud began to march to the north Kitchener was ready for him.

The Atbara

Mahmud and Osman Digna, with some 12,000 good fighting men and several notable Emirs, had concentrated on the eastern bank of the Nile round Shendy, and marching across the desert had struck the Atbara at Nakheila, about 35 miles from its confluence with the Nile. Kitchener, while holding the junction point of the rivers at Atbara Fort, massed the remainder of his force at Res el Hudi on the Atbara, prepared either to attack the dervishes in flank if they moved north or to fall on them in their camp if they remained inert. The reconnaissances showed that the dervishes had fortified their camp in the thick scrub, and that the dem could best be attacked from the desert side. An attack seemed likely to be costly, and Kitchener hoped that the dervishes, who were short of food, would either attack the Anglo-Egyptian zariba or offer a fight in the open field. The dervishes did not move, and not even a successful raid on Shendy by the gunboats carrying troops affected their decision. After some telegraphic communications with Lord Cromer, Kitchener drew nearer to his enemy, advancing first to Abadar and then to Umdabia. Here he was within striking distance, and in the evening of April 7 the whole force marched silently out into the desert, and after a well-executed night march came within sight of Mahmud’s lines at 3 a.m. on the morning of Good Friday, April 8. A halt was made about 600 yards from the trenches and the artillery opened fire, while the infantry was reformed for the assault, Hunter’s Sudanese on the right and the British on the left. At 7.40 a.m. Kitchener ordered the advance. A sustained fire of musketry broke out from the dervish entrenchments and was returned with interest by the British and Sudanese, who advanced firing without halting and as steadily as on parade. The din was terrific and the attack irresistible. In less than a quarter of an hour the dervish zariba was torn aside and Kitchener’s troops inundated the defences. The dervishes stood well and even attempted counter-attacks, but they were swept out of the dem into the river and the bush, leaving 1,700 dead in the trenches, including many Emirs. The wily Osman escaped, but Mahmud was made prisoner, while comparatively few of the dervishes who escaped regained Khartum. In this brief but fierce and decisive action the Anglo-Egyptian force suffered 551 casualties.