скачать книгу бесплатно

EIGHT WEEKS AFTER THE ACCIDENT

Thursday 26th April

I feel like a balloon on a string, floating above the pavement. Alex’s hand is wrapped tightly around mine but I can’t feel the pressure of his fingers on my skin. I can’t feel anything. Not the pavement under my feet, not the wind on my cheeks, not even my laboured breath in my throat. Tony, my stepdad, is walking ahead of us, his white hair waving this way and that as the wind lifts and shakes it. His black suit is too tight across his shoulders and every now and then he tugs at the hem. When he isn’t pulling at his clothes he’s glancing back at me, over his shoulder.

‘All right?’ he mouths.

I nod, even though it feels like he’s looking straight through me, talking to someone further down the street. I barely recognised the woman who stared back at me from the mirror this morning as she pulled on the white blouse, grey suit and black heels that had been laid out on the bed for her. I knew it was me in the mirror but it was like looking at a photograph of myself as a child. I could see the similarity in the eyes, the lips and the stance but there was a disconnection. Me, and not me, all at the same time. I barely slept last night. While Alex snored softly beside me, curled up and hugging a pillow, I lay on my back and stared at the dark ceiling. When I did fall asleep, sometime after three, it wasn’t for long. I woke suddenly at five, gasping, shrieking and clawing at the duvet. I’d had my hospital dream again, the one about the faceless person staring at me.

‘It’s going to be okay, sweetheart,’ Mum says now, trotting along beside me, her cheeks flushed red, the thin skin around her eyes creased with worry. When we got out of the car she took my right hand and Alex took my left. I felt like a child, about to be swung into the air but with fear in my belly rather than glee. At some point Mum must have let me go because now her hands are clenched into fists at her sides.

‘Anna.’ Mum’s gloved hand brushes the arm of my coat. ‘This isn’t about you, love. You’re not the one on trial. You’re a witness. Just tell the court what happened.’

Just the court: the judge, the jury, the lorry driver, the public, the press, and the family and friends of my colleagues. I need to stand up in front of all of those people and relive what happened eight weeks ago. If I didn’t feel so numb, I’d be terrified.

‘Anna!’

‘Over here!’

‘Anna!’

‘Mr Laing!’

‘Mr Khan!’

The noise overwhelms me before the bodies do. Everywhere I look there are people, necks craned, arms reaching in the air – some with microphones, others with cameras – and they’re all shouting. My stepdad wraps an arm around my shoulders and pulls me close.

‘Give her some space!’ He raises an arm and swipes at a camera that’s just been shoved in my face. ‘Out of the way! Just get out of the bloody way, you imbeciles.’

As Tony angles me out of the crowd I search desperately for Mum and Alex but they’re still trapped in the throng of people by the courthouse entrance.

‘Anna! Anna!’ A blonde woman in her early forties in a pink blouse and a puffy black gilet presses up against me and holds a digital Dictaphone just under my chin. ‘Are you satisfied with the verdict? A two-year sentence and two of your colleagues are dead?’

I stare at her, too shocked to speak, but she registers the turn of my head as interest and continues to question me.

‘Will you go back to work at Tornado Media? Was that your boyfriend you were with?’

‘You’re having trouble sleeping, aren’t you?’ a different voice asks.

I twist round to see who asked the question but there’s a sea of people following us down the steps – dozens of men in suits, photographers in jeans and anoraks, a dark-haired woman in a bright red jacket, an older lady with permed white hair, my mother – pink-cheeked and worried – and, on the other side of the group from her, the thin, anxious shape of my boyfriend.

The blonde to my right nudges me. ‘Anna, do you feel responsible in any way?’

‘What?’ Somehow, in the roar, Tony heard her question. Someone behind me bumps against me as my stepdad stops sharply. ‘You bloody what?’

It’s like a film, freeze-framed, the way the crowd around us suddenly falls silent and stops moving.

The blonde smiles tightly at Tony. ‘Mr Willis, is it?’

‘Mr Fielding actually, who’s asking?’

‘Anabelle Chance, Evening Standard. I was just asking your daughter if she felt in any way responsible for what happened.’

The skin on my stepdad’s neck flushes red above the white collar of his shirt. ‘Are you bloody kidding me?’ He stares around at the crowd. ‘Can she actually say that?’

‘It was just a question, Mr Fielding. Anna’ – she tries to hand me a business card – ‘if you’d ever like to chat then give me a—’

He knocks her hand away. ‘You’re treading a very fine line. Now, get out of our way, before I make you.’

Mum and Alex wrap around us like a protective shield, Alex beside me, Mum next to Tony, as we hurry away from the noise and chaos of the courtroom.

‘Have you got a tissue, love?’ Mum asks as we reach the car. ‘You’ve got mascara all down your face.’

I touch a hand to my cheeks, surprised to find that they’re wet.

‘Yes, I’ve …’ I reach a hand into my suit pocket and feel the soft squish of a packet of Kleenex. But there’s something else beside them, something hard with sharp corners, something I don’t remember putting into my pocket when I got ready this morning. It’s a postcard. The background is blue with white words forming the shape of a dagger. The words turn red as they near the point of the blade and a single drop of blood drips onto the title: The Tragedy of Macbeth.

‘What’s that?’ Mum asks as I flip the card over.

I shake my head. ‘I don’t know.’

There are two words written on the back, in large, looping letters:

For Anna

I look from Mum, to Dad and then to Alex. ‘Did one of you put this in my pocket?’

When they all shake their heads, I flip it back over and read the quote:

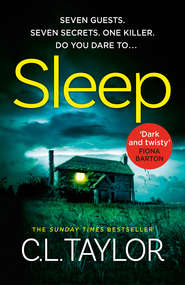

Methought I heard a voice cry ‘Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep’ – the innocent sleep, Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleave of care, The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course, Chief nourisher in life’s feast.

I know this quote from studying Macbeth at A-level. It’s Macbeth talking to Lady Macbeth about the frightening things that have happened since he murdered King Duncan.

‘Anna?’ Alex says. ‘Are you okay? You’ve gone very pale.’

I glance back towards the courthouse and the throng of faceless people milling around.

‘Someone put this in my pocket.’

‘It wasn’t that bloody journalist, was it?’ Tony says. ‘Because I’ll get on the phone to her editor if I need to. I won’t have her harassing you like this.’

‘Let me see that.’ Alex leans over my shoulder and peers at the card. ‘Is that a quote from Shakespeare?’

‘It’s Macbeth telling Lady Macbeth about a voice he heard telling him he’ll never sleep again.’

‘Oh, that’s horrible.’ Mum runs her hands up and down her arms. ‘Who’d give you something like that?’

‘Here, give me that.’ Tony takes the card from my fingers, rips it into tiny pieces and then drops them into a drain. ‘There. Gone. Don’t give it a second thought, love.’

No one mentions it all the way home but the words rest in my brain like a weight.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_311d9ab3-11db-5950-b5f5-7dab838eacab)

Steve (#ulink_311d9ab3-11db-5950-b5f5-7dab838eacab)

Saturday 28th April

Steve Laing bows his head and crosses himself as he crouches beside his son’s grave. He’s not a Catholic but it feels like the right thing to do. It shows respect. He touches a hand to the gravestone, tracing a finger over the cold imprint of his son’s name, and his chest burns with grief and rage. He still can’t quite believe it, that his son’s body is buried deep in the ground, six feet below him. It doesn’t feel real. How can it be? Freddy was young, he was strong, he went to the gym three times a week and played squash every Saturday. He’d had chickenpox as a kid. Broken his arm when he fell off the slide. But he wasn’t one of those kids in the park with snot dribbling over his top lip. He was healthy, hardly had a day off school. The only time Steve had had to take him to A&E was when he got so pissed at a house party for a mate’s fifteenth birthday that he ran into a glass door and knocked himself out. When he came round he claimed he’d had his drink spiked. Steve could see in the twitch of his lips that he was lying but he admired his gumption. Freddy could be a gobby little shit, always trying to talk himself out of trouble. He was loud too. He filled the house with his booming voice and his clumsy-arsed ways. Steve had lost track of the number of times he’d shouted at him to ‘keep the bloody noise down’ when he crashed into the house late at night, clattering around in the dishwasher or bashing every pot and pan together as he tried to make himself a snack after a drinking session with his mates. But he was never angry with him, not really. Freddy was all he had after Juliet had died. Fucking cancer, stealing the kid’s mum away from him five days before his eleventh birthday. If cancer were a person he’d have beaten the shit out of it and smashed its face to a pulp.

The house is quiet now. So bloody quiet it makes him want to turn on every stereo and sound system in the place and scream at the top of his voice. That’s the worst thing about death, the silence it leaves behind. But not in Steve’s head, there’s no peace there. Some days he feels as though he’s going mad, all those thoughts, buzzing around like wasps. He kept them quiet for a bit – planning the funeral and preparing for the trial – but they started up again afterwards, louder and angrier than ever. It’s the powerlessness he can’t cope with. He couldn’t save Freddy. He couldn’t grab hold of the surgeon’s knife, plunge his hand into his son’s chest and massage his heart back to life. He couldn’t speed up the police investigation. He couldn’t talk to the CPS and, other than a prepared statement, he couldn’t speak to the judge or jury. His son had been taken from him and he couldn’t do a fucking thing about it. ‘Trust us,’ the police told him. ‘Let us do our job.’ But they hadn’t, had they? Not really. Not them, not the CPS and not the fucking judge.

He traces a finger over his son’s birth and death dates. Twenty-four. Just twenty-four. At the funeral the vicar had said something about an ‘everlasting sleep’ that had really riled him. Death wasn’t like sleep. It wasn’t relaxing. You didn’t dream and you couldn’t be woken up. A dark cloud of despair had descended when the last of the mourners left Freddy’s grave. For most of them it would be the only time they’d visit it. They’d miss him, of course they would, but they’d get back on with their lives, whereas Steve felt his had been indefinitely paused.

It was his mate Jim who’d thrown him a lifeline. ‘If you feel that justice hasn’t been done, mate, then maybe you need to mete it out yourself. If you know where she is I can send someone after her. She won’t even see them coming. If that’s what you want.’

Steve wasn’t sure if it was. He prided himself on being a gentleman. He’d never once lifted his hand to a woman. But it was different if a woman was a murderer, wasn’t it? He’d have had no qualms about hurting Myra Hindley or Rose West. And that’s what this woman was, wasn’t it? A murderer. She’d taken the lives of two young people and crippled another. She hadn’t looked him in the eye at the trial. Hadn’t even acknowledged he was there. But she will. She’ll know who Steve Laing is, and she’ll remember his son. He’ll make sure of that.

Chapter 8 (#ulink_72bf9af1-6bfb-5143-bd2f-5fd590b911b1)

Anna (#ulink_72bf9af1-6bfb-5143-bd2f-5fd590b911b1)

Wednesday 2nd May

Our flat is a very different place at four o’clock in the morning. Unusually for London, the air is cool and still, the bedroom wrapped in shadows, the darkness punctuated only by the glow of streetlamps slipping through the gap in the curtains. Alex is asleep, curled up on his side, hugging the duvet. He came back from work yesterday evening to find me wrapped in a blanket on the sofa, staring dully at the TV. He stood in the doorway, watching me, waiting for an acknowledgement.

‘Hi,’ I said, then let my gaze return to the TV. A single glance was enough to assess his mood: rigid posture, tight jaw, cold eyes. He was angling for a fight. Again.

‘What this?’ He picked up the empty mug from the side table.

‘A mug.’

‘And this?’ He picked up a plate.

I looked at him. ‘What are you doing?’

‘What are you doing?’

He stalked out of the living room, mug and plate in hand. I heard them crash into the sink then the sound of the fridge door opening and closing and a curt fucking hell.

‘Anna.’ He was back in the doorway again. ‘There’s no food in the house. You said you’d go to the supermarket.’

‘I did.’

‘And?’

‘Someone followed me.’

‘Not again.’ He rested his head against the white glossed wood of the door frame. ‘Anna. You need to let this go. Steve Laing is not out to get you. The person who was responsible – the lorry driver, not you – has been charged and sent to prison. The coroner’s court case has been dismissed. It’s finished. Over.’

He didn’t understand. How could he? I hadn’t got any proof that someone had been following me. I hadn’t confronted them or taken their photo. I didn’t even know what they looked like, but I’d felt them watching me. I’d been fine leaving the house. I’d made it all the way to Tesco without feeling a horrible prickling sensation from the base of my skull to midway down my spine. The sun was shining and I was in a good mood because I’d just binge-watched three episodes of Catastrophe. Steve Laing hadn’t crossed my mind once and then it happened, the absolute certainty that someone was standing behind me, watching me as I bent down to take a loaf off the shelf. When I turned around there were five other people in the aisle – a man in a suit, an older woman, a woman about my age and another woman, slightly older than me with a toddler in a buggy. The child stared me out, his blue eyes wide and anxious. His mother looked down at him, at me, and then wheeled the buggy around and disappeared back down the aisle. Irritated with myself for overreacting, I headed straight to the tills with my basket. It wasn’t until I got home that I realised I’d forgotten half the things Alex had asked me to buy.

‘Did you ring Tim today?’ He crossed his arms over his chest.

‘Yeah.’

‘And?’

‘I gave my notice.’

He raised his eyes to the ceiling. ‘I’m struggling to pay the bills as it is. If this is a permanent situation then …’ He sighed heavily. ‘I really don’t think I can deal with this, Anna. I knew you’d be a bit … upset … for a while but I can’t live like this. If you’re not thrashing around in bed because you can’t sleep you’re sitting around in jogging bottoms watching reruns of Friends. Have you even had a shower today?’

In another life, the life I lived before my world was shattered, I would have bit back at Alex and told him that maybe he should be a bit more sympathetic. Instead I looked at him and said, ‘It’s not working, is it? Between us?’

‘It’s …’ He looked down at the grubby beige carpet and shook his head. ‘No, it’s not.’

I’d imagined this conversation in my head a hundred times since the accident, but actually having it was surreal. I’d expected to burst into tears or feel a jagged pain in my chest. Instead I felt detached, as though I were watching the break-up scene happen to two other people. We’d been drifting apart for a long time, way before the accident, but you’d have to be a cruel kind of bastard to leave someone when they needed you most. We didn’t dislike each other, we hadn’t had blazing rows or shagged someone else or been cruel, but we were living separate lives. We weren’t even sharing the same bed any more, not really. There might be an hour or two – between my insomnia and Alex getting up for work – when we lay on the same sheet but we rarely touched. I couldn’t remember the last time he’d kissed me goodbye or hello. And the most telling thing was, I didn’t really mind.

‘What do you want to do?’ I asked. ‘Do you want to keep the flat?’

He looked shocked. He’d come back from work expecting a fight. He might have secretly wanted this but he hadn’t expected us to have this conversation now.

‘I’m happy for you to have it,’ I said. ‘I’ll go back to Reading and live with Mum and Tony for a bit.’

He looked up and met my gaze but I couldn’t read the expression in his eyes. ‘You’ve been thinking about this for a while, haven’t you? Us splitting up?’

‘Haven’t you?’

The air between us was suddenly very still, heavy with sadness.

‘Are you moving out today?’ He glanced at the open bedroom door and the room beyond it, looking for suitcases or signs that I’d already started getting my things together.

I looked at the kitchen clock. It was after seven. ‘I don’t know. It’s probably too late.’

‘Good.’

‘Good?’

‘I’m glad you’re staying tonight. I’m not sure I could cope with you just upping and leaving. I feel a bit …’

‘Shocked?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I know what you mean.’ I paused, suddenly unsure whether I’d misread the situation. ‘You do want this, don’t you, Alex?’

‘Yeah, yeah, I do. It’s just … weird. I feel …’ He faltered. ‘I feel like I need to give you a hug or something.’

‘Okay, sure.’ I said yes only because saying no would have been harder.