Полная версия:

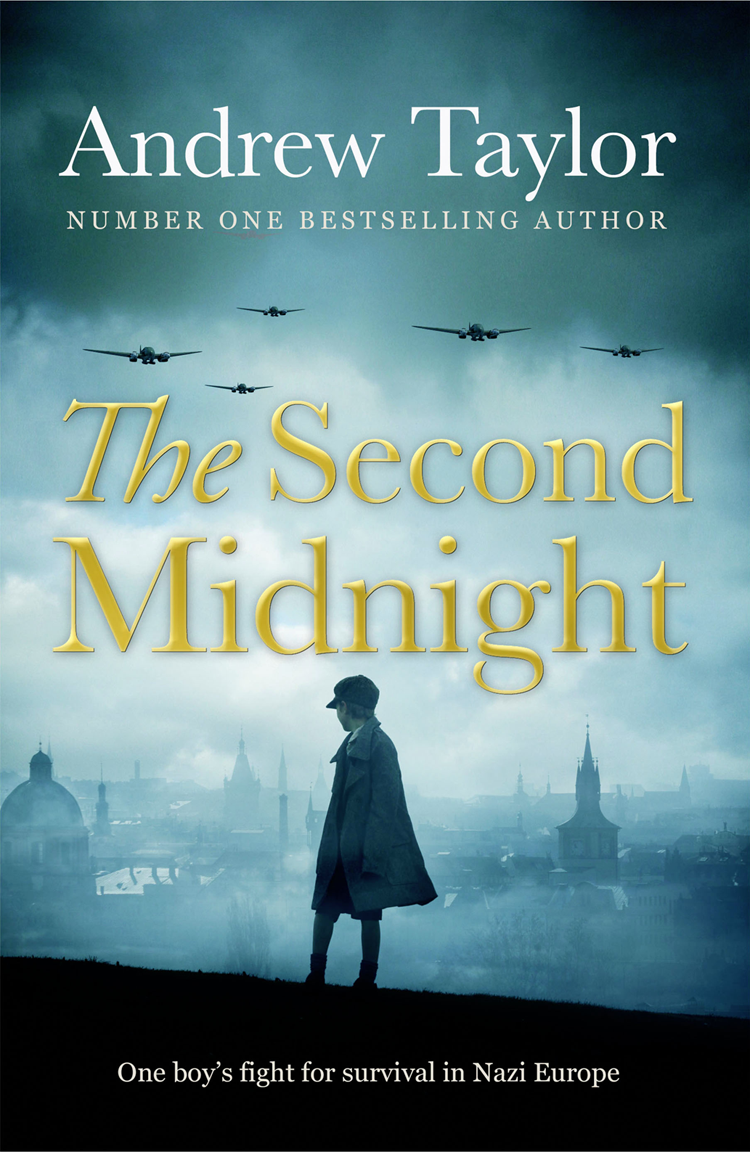

The Second Midnight

THE SECOND MIDNIGHT

Andrew Taylor

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in the United Kingdom by Collins 1988

This edition published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Lydmouth Ltd 1987

Cover design by www.mulcaheydesign.com © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Mark Owen / Trevillion Images (boy looking over city), Shutterstock.com (all other images)

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008341831

Ebook Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008341848

Version: 2019-07-16

Dedication

For C. and L.T.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

I: Pre-War 1939

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

II: War 1939–45

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

III: Postwar 1945–46

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

IV: Cold War 1955–56

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Epilogue

Keep Reading …

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

George Farrar had his first inkling that something was wrong when he collected his room key from reception.

The manager himself was behind the desk. He was a plump Viennese, almost as small as Farrar himself, and he always wore a flower in the lapel of his black coat. He was also a compulsive talker.

Tonight, however, he produced the key as soon as Farrar reached the desk and slapped it down on the counter between them. Immediately afterwards he bent his head over the register, as if the pressure of work prevented him from exchanging pleasantries with his guests.

‘Any messages?’ Farrar said. He was hoping that William McQueen might have telephoned.

The manager didn’t raise his head. ‘No, Herr Farrar.’

Farrar noticed that the white carnation was beginning to wilt. He also noticed that the manager’s face was shiny with sweat. Still, it was uncomfortably warm in the foyer.

He said goodnight and took the lift up to his floor. A tall man wearing a camelhair overcoat came up with him. He was smoking a cigar and had small, sad eyes.

They both wanted the same floor. The tall man gave a polite little bow when they reached it, indicating that Farrar should leave the lift first. Farrar smiled his thanks.

The long corridor was empty. Farrar walked quickly to his door; behind him he could hear the soft, slow pad of the other man’s footsteps. He unlocked the door and opened it; his hand brushed against the light switch.

Everything happened very suddenly. A hand slammed into the small of his back, propelling him into the room. Simultaneously, he saw that the carpet was strewn with his belongings. Another man was lying on the bed, with his hands behind his head. He was smiling. When Farrar tripped over his own upturned suitcase, the smile became a chuckle.

Behind him, Farrar heard a click as the tall man locked the door.

The man on the bed stopped chuckling. Farrar’s stomach lurched as he recognized the Bavarian he had met last night.

The Bavarian raised his heavy black eyebrows. ‘And how is our lovely Gretl this evening?’

Farrar groped for his glasses, which had slid to the foot of the bed. Camelhair brushed his cheek. A large brown shoe stamped on the glasses and twisted them into the carpet.

The tall man sucked in his breath. ‘Ach,’ he said. ‘I am so clumsy.’

‘What a pity,’ said the man on the bed. ‘Still, accidents happen.’

Farrar got slowly to his feet; his muscles tightened, ready to receive a blow from the tall man. He moved more slowly than he needed, pretending the fall had winded him. His own stupidity angered him: last night he had assumed that the man on the bed was nothing more than a tourist who had had too much to drink; he should have known better. He remembered the manager’s behaviour and realized that his visitors must be police of some sort: German, not Austrian. He was a fool to have run any unnecessary risks before he had seen William McQueen.

‘Gretl,’ the man on the bed said conversationally, ‘won’t be lovely for much longer.’ Without any change of tone he added, ‘This room is a pigsty. Tidy it up, Farrar.’

Did they know? Had they found it?

Farrar had the answer to the second question as soon as he picked up the suitcase: it was appreciably lighter than it should have been. He scooped up a pile of shirts and threw them into the case.

Sweet Jesus, he thought. Please not the Gestapo.

‘Neatly, Farrar. You get so much more in if you pack neatly, don’t you?’

‘Look, I’m sorry about last night,’ Farrar said quickly. His German was fast and fluent, and he had a salesman’s confidence in the power of his own voice. ‘I’d had a bit to drink and the girl—’

The tall man slapped him. ‘Silence, please,’ he said politely.

Farrar picked himself up again. Some clothes went in the suitcase, others in the wardrobe and the chest of drawers. Meanwhile, the man on the bed leafed through Farrar’s order book. Farrar noticed that the thieving bastards had even been at his brandy: the bottle, nearly empty, was on the bedside table; beside it was a tumbler with a couple of inches of brandy still in it.

The man on the bed looked up. ‘Business has not been good lately?’

Farrar nodded. There wasn’t much demand for boxed sets of British Grenadiers in the Third Reich. That was one reason why he had taken the other job when they offered it to him.

‘I expect you find it hard to make ends meet.’

Again, Farrar nodded. It seemed safer to agree. Besides, the man on the bed was quite right. He wondered whether they were going to beat him up before they arrested him, or wait until they had him in custody.

Escape was out of the question. His captors’ combined weight was three or four times his own; and both men would be armed. The door was locked. Even if he could open the window and dive through, he doubted if he would survive the drop of fifty or sixty feet to the street below. Shouting for help would be useless, for it was obvious that they had the cooperation of the manager.

But they wouldn’t kill him – he was sure of that. A murdered British citizen would lead to awkward questions, even in Vienna. They would interrogate him, of course, and if he was dead he couldn’t tell them anything. But the worst he had to fear was a jail sentence and perhaps a little preliminary suffering. They might not realize the significance of what they had found.

The man on the bed tore a blank page from the order book and wrote something on it with a silver pencil.

Farrar bundled a pair of shoes into the bottom of the wardrobe. At last the room was clear.

The man in the camelhair coat patted his shoulder. ‘Gut,’ he said encouragingly. ‘Sehr gut.’

‘Have a drink,’ said the man on the bed. He beckoned Farrar closer and jerked his head towards the tumbler. ‘Go on, drink,’ he said irritably. ‘It may be your last chance for some time.’

Farrar picked up the glass. The probable consequences of throwing its contents into the Bavarian’s face chased through his mind.

The Bavarian shook his head. ‘Don’t be silly, Farrar. There are two of us.’

‘Hurry, please,’ the man in the camelhair coat said. He looked ostentatiously at his watch.

Farrar shrugged. He picked up the glass and had his last drink.

George Farrar died on Wednesday 15 February 1939.

The fact that he had died was more important than how and why, at least to Michael. But, much later, Michael became curious about all aspects of the little man’s death. This was because he came to see the murder of Farrar as the starting point for what came afterwards. He realized that this was an arbitrary choice – equally logically, he might have chosen Farrar’s birth, or the Anschluss, or even (to stretch a point) the Great War.

But, being an artist of sorts, he considered that human beings had a fundamental need to create patterns from the chaos of history and from their own messy lives. A pattern had to start somewhere: even the author of Genesis had had to face up to this problem: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

So Michael’s pattern began with Farrar’s death. If Farrar had reached London the following weekend, a World War might have taken a slightly different course; his death sent ripples even further into the future; it touched, perhaps marginally, on the rise and fall of empires.

In the final analysis, however, Michael was more concerned with the effects of Farrar’s death on himself and on people he was later to know. That was where it mattered. Michael took things personally, which was why he was never particularly successful at his job. Uncle Claude never made that mistake.

Despite the fact that Michael had never met Farrar, he came to feel an almost proprietorial interest in him. In the years to come, he collected information about him.

At the time of his death, Farrar was thirty-five. He was five feet two and reputed to be hot-tempered. He had a widowed mother who lived in Worthing. Some time afterwards, Michael checked to see if His Majesty’s Government had seen fit to grant Mrs Farrar a pension. He was not surprised to find that it hadn’t. HMG, probably in the person of Uncle Claude, had used a Gestapo lie to avoid spending a few hundred pounds on an old lady who could give nothing in return. That was typical.

Farrar had worked as a travelling salesman on the Continent since 1936. He was employed by a struggling British toy firm which had built its reputation on the manufacture of toy soldiers. Z Organization had recruited him as a courier in Zurich on 8 December 1938.

Those were the salient facts about Farrar’s life. The facts about the manner of his death were more difficult to establish. Michael had access to Z Organization’s files; but these were sketchy at the best of times and they were particularly bad for Vienna after the Nazis took over. Later he was able to use the SIS Registry, but here the facts were even thinner on the ground. It was true that the Vienna Station had more or less recovered from the disruption of the Anschluss by this time. The problem was that no one there had any interest in Farrar; they had no reason to disbelieve the official story, and hence no reason to investigate it. In 1939, few people in the service were aware that SIS was operating in tandem with a changeling half-brother called Z.

Eventually Michael was able to consult the Vienna police file, though that was useful more for what it omitted than for what it included. According to the civil police, George Farrar died around midnight in room 47 of the Hotel Franz Josef on the Plosslgasse. The body was found the following morning by the chambermaid. Farrar was fully dressed and lying supine on his bed; there were cherry-pink patches on his skin. The gas was on but unlit, and the cracks around the door and the window had been clumsily sealed with newspapers and towels. The chambermaid turned off the gas and fetched the manager; the manager called the police.

The police found the remains of a bottle of brandy, an empty glass, the room key and a scrap of paper on the bedside table. Four English words had been scrawled in pencil on the paper: I can’t go on. There was no reason to doubt that they had been written by the dead man, though the only standards of comparison were a few notes in Farrar’s order book and his entry in the hotel register.

Further investigation showed that Farrar’s financial affairs were in a bad way. The manager and the chambermaid testified that Herr Farrar had seemed distraught and depressed. Another witness came forward – a public-spirited Bavarian tourist, who claimed to have met Farrar in a café on the Ringstrasse a few hours before he died. According to the obliging Bavarian, Farrar had been drunk and talking of suicide; he blamed his problems on the international Jewish conspiracy.

Michael didn’t dispute the evidence in the police file, except perhaps the testimonies about Farrar’s state of mind. Of course it was curious that no one had thought to test the body for traces of cyanide – for cyanide, like carbon monoxide, left patches of lividity on a corpse. It was curious but not necessarily significant. The Viennese police sent Farrar’s belongings to the British Embassy, which transmitted them to Worthing. They were itemized with Teutonic thoroughness on the file – right down to Handkerchiefs, 6, Pair of Glasses (Broken) and Book Entitled The Black Gang by Sapper.

But someone had been careless: there was no mention of a pencil.

Z Organization had a man in Vienna – indeed, William McQueen had intended to contact Farrar on the Thursday to pick up the gold. McQueen’s cover was at risk, but he made cautious enquiries after Farrar’s death. He found a waiter from the Franz Josef who admitted, when suitably primed with alcohol, that something odd had gone on that night. The manager had taken over the receptionist’s evening shift. There was a rumour among the staff that two men from the Hotel Metropole had been seen in the Franz Josef on Wednesday night.

The Hotel Metropole was the Vienna headquarters of the Gestapo.

The gold was no longer among Farrar’s belongings, but that was only to be expected. Uncle Claude and everyone else drew the obvious inference: the Gestapo had somehow identified Farrar as a courier; they had killed him and taken the gold. The fact that they had killed him – rather than used him as bait – suggested that they already knew for whom the gold was intended. Perhaps Farrar had talked before he died. As a result, Uncle Claude decided his resources were better used elsewhere: McQueen was transferred to Basel, and the Z network in Vienna never amounted to much.

The real irony only became apparent years later, when Michael was interrogating a Gestapo officer who had made something of a name for himself in wartime Holland. Knowing that his prisoner had previously served in Vienna, Michael threw in a question about the Farrar affair.

The officer, who was in the talkative, confiding phase of his interrogation, remembered it well, because of the gold. Farrar, it seemed, had been a womanizer whose bravado was in inverse proportion to his height. On the Tuesday night he had quarrelled with a man he believed to be a German tourist. The cause of the dispute was the favours of a prostitute; and the scene of it was that bar on the Ringstrasse. Farrar had won.

The following evening, the plainclothes man and a colleague had paid a visit to the Franz Josef, intending merely to teach Farrar a lesson. Farrar was out, but the manager gave them a passkey to his room. While they were waiting, they discovered the gold concealed in his suitcase. The presence of undeclared gold marks worth nearly a thousand pounds sterling didn’t suggest to the two policemen that Farrar was engaged in espionage. Why should it have done? In those days, plenty of people were trying to move hard currency out of Austria for the most personal of reasons, and foreigners, with their relative freedom to cross the frontiers of the Reich, were often used for the purpose.

On balance, it was safer to kill Farrar if they wanted to take the gold. The manager of the Franz Josef was persuaded to cooperate; he didn’t want to lose his job and possibly his liberty. The officers had to give Michael’s captive a percentage of the proceeds, because his authority was needed to ensure that the civil police drew the right conclusions.

The police did as they were told. It was, they were informed, a political matter which concerned the security of the Reich. And there was the irony: the lie was perfectly true.

George Farrar was murdered in Vienna on the 15 February 1939: that was the beginning of Michael’s pattern.

It was an arbitrary choice, yes: but at least it made the whole affair seem personal – and therefore easier to bear. It showed that affairs of state were ultimately dependent on the motives and actions of apparently insignificant individuals. What happened after Farrar’s death was made somehow more intelligible by the idea that it could be traced back to the greed of two secret policemen, the whim of a Viennese whore and the libido of a commercial traveller in toys.

One

The ivory ruler snapped in two as it hit the top of the desk. Three inches of it ricocheted off the polished oak and landed on Hugh’s shoe. He jumped backward. The remaining nine inches stayed in Alfred Kendall’s hand.

His father’s knuckles, Hugh noticed, were the same colour as the ruler.

Alfred Kendall turned slowly in his chair. He was still dressed in his City clothes, which lent an odd formality to the proceedings.

‘Do you mean to tell me that the headmaster is lying?’

‘No, Father.’ Hugh’s hands clenched behind his back. His body was treacherously determined to tremble. ‘Mr Jervis was mistaken. I—’

‘Don’t lie to me, boy. I’ve known Mr Jervis for a good ten years. He isn’t a fool.’ Kendall tapped the letter in front of him. ‘Nor is he the sort of man to fling around wild accusations.’

Hugh’s vision blurred. ‘I didn’t do it.’

The words came out more loudly than he had intended. For a moment his father stared contemptuously at him. Hugh tried to look away. It was almost with relief that he saw his father begin to gnaw his lower lip with a long, yellow tooth. This was almost invariably a preliminary to speech.

‘Never did I think I should read such a letter about a son of mine.’ Kendall’s voice hardened. ‘You don’t seem to realize that you’ve brought shame on the entire family.’

Hugh shrugged. It was a gesture of discomfort, not insolence, but his father interpreted it otherwise. Kendall’s slap caught Hugh unawares: he reeled back against the table.

‘That,’ his father said slowly, ‘is just a foretaste of what you should expect. Don’t snivel. Listen to what Mr Jervis has to say about you. “Dear Captain Kendall, It is with deep regret that I have been forced to expel your son Hugh from the school, with immediate effect. One of his classmates had foolishly brought a ten-shilling note to school. Just before luncheon, the boy reported it had been stolen. It was subsequently found in the pocket of Hugh’s overcoat. Hugh, I am afraid, made matters worse by trying to dissemble his guilt. For the sake of the other boys in my charge, I cannot permit a pupil who has proved to be both a thief and a liar to remain for a moment longer than necessary. I will forward the termly account at a later date.”

‘The termly account, you note. In the circumstances, Mr Jervis is quite within his rights to charge for the entire Lent term. Have you any idea what the fees are like for a first-rate prep school like Thameside College? Your brother used his time there to win a scholarship. But you have wantonly wasted your opportunities from the first. I scrimp and save to give you the finest education available in England – and this is how you repay me. Do you think that’s fair? Do you think that’s reasonable? Answer me, boy.’

Hugh’s eyes were heavy with tears. Humiliation bred anger, which in turn created a brief and desperate courage. ‘I … I thought—’

‘Don’t mumble at me. And don’t you know that tears are unmanly?’

‘I thought Aunt Vida was paying my fees.’

Purple blotches appeared on Kendall’s face. He jerked himself out of his chair and towered over Hugh.

‘You impudent little wretch,’ he said softly. ‘You will regret that, I promise you.’

Hugh’s courage evaporated. He had been stupid to mention Aunt Vida. None of the children was supposed to know that she paid their school fees. But Stephen had found out years ago from their aunt’s housekeeper.

This time the blow was a back-hander. The edge of Kendall’s wedding ring cut into the skin over Hugh’s cheekbone. He cannoned into the table and fell to the ground.

‘Get up. And don’t you dare bleed on the carpet.’

Hugh got slowly to his feet. He touched his cheek and looked at the smear of blood on his fingers.

‘Handkerchief.’

Hugh pulled out the grubby ball of linen from his trouser pocket. He dabbed his face, conscious that his father was still looming over him. Adults were so unfairly large.

‘You despicable little animal,’ Kendall whispered.

Hugh held back a sob with difficulty. He knew he would cry sooner or later, but he was determined to put it off for as long as possible. What was happening to him was unjust; yet for some reason that didn’t seem important beside the fact that he disgusted his father. He was bitterly ashamed of himself. He wished he were dead.

‘Bring me the cane. The thinner one.’

The two canes were kept in the corner between the wall and the end of the bookcase. Hugh sometimes daydreamed of burning them. The thicker one, curiously enough, was less painful. The thin one was longer and more supple; it hissed in the air, gathering venom as it swung.

He handed it to his father. It was part of the ritual that the victim should present the means of punishment to the executioner.

Alfred Kendall tapped the cane against one pin-striped trouser leg. ‘You know what to do. Waiting won’t make it easier. I can promise you that.’

Hugh turned away and unhooked the S-shaped metal snake that held up his trousers. His fingers groped at the buttons. When the last one was undone, the trousers fell to his ankles. He shuffled across the room to the low armchair where his mother sat in the evenings. He could feel a draught from somewhere on the back of his knees.

The chair had a low back. Hugh stretched over it, extending his arms along the chair’s arms for support. His mother’s knitting bag was on the seat of the chair. He could see the purple wool of the jersey she was knitting for Stephen.

His father’s heavy footsteps advanced towards him and then retreated. This, too, was part of the ritual: Alfred Kendall was a man who liked to take measurements. Hugh knew there were four paces between the desk and the chair. To be precise, there were three paces and a little jump. After the jump, his father would grunt like someone straining on a lavatory. Then would come the pain.