Полная версия:

God’s Fugitive

GOD’S FUGITIVE

The Life of Charles Montagu Doughty

Andrew Taylor

DEDICATION

Looking in one direction,

this book is dedicated to

HARRY TAYLOR

and in the other

to

SAM, ABIGAIL AND REBECCA

EPIGRAPH

The traveller must be himself in men’s eyes, a man worthy to live under the bent of God’s heaven, and were it without a religion; he is such who has a clean human heart and longsuffering under his bare shirt: it is enough, and though the way be full of harms, he may travel to the ends of the world.

Travels in Arabia Deserta, i, p. 56

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

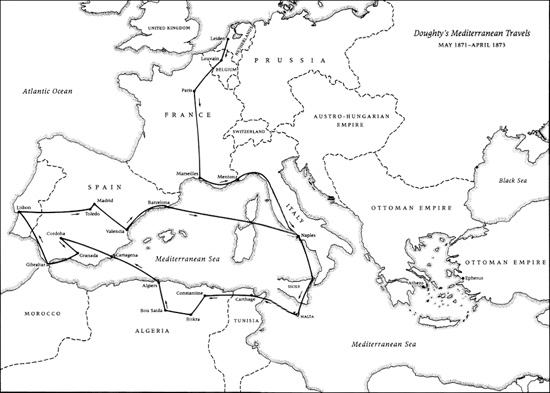

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Afterword

Keep Reading

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

Author’s Note

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

FOREWORD

Charles Montagu Doughty was the foremost Arabian explorer of his or any other age. His two years of wandering with the bedu through the oasis towns and deserts started a tradition of British exploration and discovery by travellers who acknowledged him as their master, and he returned to England to write one of the greatest and most original travel books.

He was that unlikely adventurer for his day, a man who would not kill – and yet he had strength and passion, and could face the threat of his own death without flinching. As a writer, he believed in his writing and in his vision when nobody else did; turning his back on exploration, he dedicated his life to poetry and struggled singlehandedly to change the direction of English literature. He lived through the greatest revolution in thought the world had ever seen, and spent a lifetime wrestling with his conscience over its consequences.

Among his admirers as an artist were George Bernard Shaw, who found Arabia Deserta inexhaustible. ‘You can open it and dip into it anywhere all the rest of your life,’ he declared.1 There were F. R. Leavis, Edwin Muir, Wyndham Lewis and, most ardent of all, T. E. Lawrence. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is, in its way, Lawrence’s own homage to Doughty.

And now he is virtually forgotten, his dense and idiosyncratic works valued by antiquarian booksellers and lovers of Arabia, but practically unknown to the readers of a simpler, less painstaking age. The achievement of his travels on foot and by camel seems overshadowed in the days of four-wheel-drive vehicles, helicopters, satellite navigation systems, supply-drops and commercial sponsorship. The great desert journeys are now all in the past. The tradition of Arabian exploration can never be recovered: it is as much a part of history today as the crossing of the Atlantic, or the search for the source of the Nile.

It was Wilfred Thesiger, another great Arabian explorer, who observed that there could never again be a camel-crossing of the desert like his own in the 1940s, or those of the explorers who went before him. ‘I was the last of the Arabian explorers, because afterwards, there were the cars,’ he said. ‘When I made my journeys in Arabia, there was no possibility of travelling in any other way than the way I went. If you could go in a car, it would turn the whole journey into a stunt.’2

Thesiger was the last of a line that included Harry St John Philby, father of the Russian spy and the dedicated servant of Ibn Saud, King of Arabia; there was Bertram Thomas, the civil servant who saved up his holidays for his desert expeditions, and became the first European to cross the Empty Quarter; and Gertrude Bell, who travelled to Arabia in the shadow of a disastrous love affair,3 and demanded that the rulers of Hail treat her like the lady she was and cash her a cheque for £200.

There were the Blunts, Wilfrid and Lady Anne, searching for a romantic Orient which never existed outside the salons of London and Paris; and of course, T. E. Lawrence himself, Lawrence of Arabia, who united the warring tribes just long enough to drive out the Turks and change the face of the Middle East for ever. All of them were passionate, even obsessive, about the desert – and above and before them all stood Charles Montagu Doughty.

The tradition had lasted less than seventy years. Before, there had been adventurers, explorers like Sir Richard Burton or William Gifford Palgrave, who disguised themselves and slipped through Arabia like thieves or spies; after Doughty, with his proud refusal to dissemble, things were never the same again.

Doughty came to Arabia almost by accident, at the end of six years’ wandering through Europe and the Middle East. Initially, he intended to investigate reports of a lost city like Petra, close by the pilgrim road to Mecca; but by the time he sailed away from Jedda two years later, he had dug more deeply into Arabia, lived more closely with the wandering bedu, than any explorer before or since. Thesiger was to collect photographs, Philby tiptoed after tiny birds, reptiles and mammals like some ghastly Angel of Death adding to his collection, and all of them gathered fossils, rocks and ‘specimens’ for the museums at home – but Doughty’s vision embraced an entire civilization.

Everything he did was on a grand scale, and the book he eventually wrote about his travels, which appeared some nine years later, covered nearly 1,200 pages. It was written in a style that mingled Elizabethan and Arabian, the rhythms of the Bible with the precision of a scientific text. And apart from being a staggering work of literary ambition, Travels in Arabia Deserta was, for many of the explorers who followed him, a first introduction to the Arab world.

‘We were in totally different parts of Arabia, so he couldn’t give me any information about the country itself, but he could give me a feel for the bedu and their way of life,’ said Thesiger, whose own book, Arabian Sands, is itself considered a classic.4 ‘It was a massive undertaking. Thomas’s books I don’t think are worth reading; Philby’s are too technical, and I don’t find them readable, but there is more in Doughty about the Arabs and their way of life than anywhere else.’

Doughty claimed later that his travelling was no more than a brief distraction in a life dedicated to poetry. But Arabia stayed with him until the day he died – as indeed it did with all the explorers. His obsessions, though, were bigger, more ambitious, than theirs – his book delving at the same time into the soul of a civilization and into the soul of a single tortured human being.

He was born into the maelstrom of the most wide-ranging revolution in the entire history of western thought, and he shared fully in an intellectual upheaval that still reverberates. Scientific disputes are usually remote, abstruse – the bitter argument centuries before, over whether the sun or the earth was at the centre of the universe, had been carried on largely among a small group of committed experts. The vast mass of the people were as unaffected as they were uncomprehending. But the twin shocks of the revolution which hit the mid nineteenth century were to shake the confident world-view of virtually every single thinking person in the western world for decades to come.

Through the early years of the century generations of comfortable certainty were being chipped away by the questing hammers of the new geologists. Not only was the world vastly older than the theologians suggested, the scientists claimed, but the natural forces that had shaped it were still at work. Two books took the argument forward – first Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, and then Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

Each was the synthesis of a dispute which had been simmering for decades, but they shifted the ground of the debate irreversibly. First the earth, and now mankind itself, was toppled from its position as the unchanging Creation of a loving God. The reassuring vision of man in the image of his Maker was altered for ever. It was by going to study the work of wind, rain, volcanoes and glaciers, peering through microscopes rather than poring over religious books, that knowledge could be won.

Doughty followed both courses. He was born into a family which, through its generations of conservative Anglican religious ministry and its respect for history and tradition, was likely to be shaken to the core by the revolution. Many people in a similar position struggled to maintain their equanimity by ignoring the scientific arguments, others by relinquishing their religious faith. Doughty, picking over fossils in the Suffolk clay, travelling to Cambridge University to study the dangerous new discipline of Natural Science, struggling with his ice-axe and notebooks over the glaciers of Norway, yet still maintaining his passionate religious sense, was caught in a lifelong dilemma.

After Cambridge, he abandoned science to turn to poetry, abandoned the new fascination with field-study to return to the library. Once again, he was delving back into the past, into the foundations and origins this time of language and literature, a self-taught philologist, linguist and anthropologist. When he set off on his travels, his copies of Chaucer, Spenser and other early English writers in his bags, it was with a closely drawn and wide-ranging intellectual map which could guide his researches in geography, geology, biology, history, anthropology and language.

But he had, too, the deeply introspective determination of a writer and a poet. His wanderings, as far as we can tell, seem to have been largely serendipitous: Doughty was blown by whatever wind took him, first around Europe, then through the Middle East and Sinai, and finally south with the Hadj caravan towards Mecca.

When he returned, it was to a life of unremitting study and contemplation as he embarked first on the story of his travels, and then on a series of epic poems that drew on his experiences, his researches and his uncompromising belief in the corruption and decadence of the English language. He saw himself as a patriot, trying to turn back the clock to a time when language and literature were fresh and pure. He failed, as people who reach back into history always do; but the attempt dominated his life, and the poetry that it created does not deserve merely to be forgotten.

In many ways, he was a man of his times: he felt a Victorian’s distaste for industrialization; he joined in the brutal, blustering patriotism of the First World War years; even his fascination with language, with the words and expressions of another age, was shared by other scholars and poets of the period. But, a sort of intellectual Howard Hughes, he read nothing of their work, and virtually nothing of other contemporary writing: the names of the leading poets and writers of his day were completely foreign to him, and he shied nervously away from the onrush of the twentieth century.

He was indeed, in the phrase he was to use many years later, ‘God’s Fugitive’.

MAP

Chapter One

There is nothing in the nature of a biography; nor could there, that I can see, be any utility in it. I was born in ’43 and left an orphan when a little child. I am now rather an invalid …

Letter to S. C. Cockerell, Christmas Day 1918

The solid, square flint tower of St Mary’s Church, Martlesham, is almost hidden among the Suffolk trees. It stands a couple of miles away from the modern village – easy to miss for the casual visitor.

Inside are the haphazard treasures of thousands of English country churches: a fifteenth-century wall painting of St Christopher, lovingly preserved; an ancient family pew recessed into a wall of the chancel, and now used to store cleaning materials; a stone font from the fifteenth century and a carved oak pulpit from the seventeenth; an ancient chest, and a few pieces of medieval stained glass gathered into a single panel. And along the walls, the carved memorials that say everything and nothing about the long-dead members of a local family – in this case, the Doughtys.

There are George Doughty, died 1798, and his wife Ann; their son Chester, who died in 1802; Major Ernest Christie Doughty, DSO, of the Suffolk Regiment, who died in 1928; his grandfather, Frederic Ernest, Rector of Martlesham for nearly thirty years. Outside, more Doughtys are at rest in the graveyard: Rear-Admiral Frederick Proby Doughty, who died in 1892, and his wife, the former Mary Arnold, with their child Beatrice May, lie there among their relatives.

Of Charles Montagu Doughty, for whom as a child Martlesham was closer to being a home than anywhere else, there is nothing: his memorial is far away, in a London crematorium. And yet the atmosphere of the simple little church, its unimpeachable, unassuming Englishness and its dignified reserve, reflect one facet of his character. As in churches all over the country, it is the list as a whole, rather than the individual names, which tells the story; of specific characters, particular lives, the memorials are all but silent. There are names, dates, an occasional mention of a life’s work, but it is the tradition, the history, not the individual, which counts.

And that, without the slightest doubt, is what Charles Doughty would have thought the proper attitude.

He always backed away from curiosity about his biography or his early life – and indeed, many Victorian children must have shared his experience of childhood as time spent in a foreign and not particularly friendly country. Even for the offspring of a family with lands, traditions and inheritances on each side going back for generations, it could be an unpredictable and precarious existence.

Doughty was born into a world of privilege and high expectations. His father, also Charles Montagu, was a clergyman, the squire of Theberton in Suffolk, and owner of family estates and properties all over the county – but it was only a few months after his birth on 19 August 1843 that the young Charles Doughty suffered the first of a series of devastating blows. His mother, Frederica, never recovered from the strain of childbirth and, at less than a year old, Doughty was motherless. He himself had not been expected to survive. ‘It is a long time since I came into the world, and so obviously a dying infant life, that I was christened by my own father almost immediately,’ he said later.1

But it was the mother, and not the child, who died, and for the rest of his life, the few people who talked to Doughty about his childhood commented on his abiding sense of bereavement. Within a year of his own marriage forty-three years later came a mirror-image of the tragedy, with his own stillborn first child carried off to the churchyard while his invalid wife lay and struggled back to health. Small wonder that later, as he gathered together in his painstaking fashion thousands of word-associations and jottings for use in his writing, among the first under the Latin heading ‘Mater’ would be ‘mother’s yearning’, ‘longing’, ‘smiling tears’ and ‘yearning love’.2

One of the first and most lasting lessons for the young Charles Doughty was that love was something that was brutally wrenched away – an ache, not a consolation.

At the end of his life, then, his writing drew not just on six decades of dedicated study, not just on the travels through Arabia which had been his formative experience, but also, crucially, upon the sense of loss which had surrounded his earliest memories. The theme repeatedly comes back to haunt him – in his last poem, Mansoul, for instance, he describes how he faced his own ‘private grief’ on his journey around the underworld. ‘Death cannot dim thy vision,’ he declares at his mother’s grave.

Long cold be those dead lips, that word ne’er spake

Unworth, unsooth; those dying lips, that kissed,

Once kisst (thy nature’s painful travail past)

This last new-born on thy dear breast, alas! …

Mother of my life’s breath, I living lift

O’er thee, these prayer-knit hands … 3

And the grief runs deeper than that simple, almost formalized Victorian sentimentality. In The Dawn in Britain, the story is told of the baby Cusmon, who was abandoned by his mother, the immortal nymph Agygia, but watched over by her throughout his life. Eventually, after his hundredth birthday, they are reunited at his death.

She stooped, and dearly kissed

That bowed down, aged man, and long embraced … 4

When he wrote that, Doughty himself was in his seventies. He is a child again, his lost mother restored, and a lifelong sense of bereavement finds its devoutly longed-for but hollow and insubstantial resolution in an old man’s dream. It is significant that he angrily denied suggestions in reviews that this was his own version of an ancient tale: ‘There is no such myth, and there is no such version,’ he declared. ‘The original is that in The Dawn in Britain itself.’5 The story clearly remained important to him: he could mourn the loss of his mother, but emotionally, he could never quite accept it.

Materially, though, both Doughty and his elder brother Henry were well provided for, their place in society apparently fixed by generations of affluence and family tradition. On both sides, the family were well-to-do, landowning gentry: the census return for Theberton for 1841, just two years before Charles’s birth and Frederica’s death, shows the Doughtys with the three-month-old Henry and five adult servants. It was a comfortable life in the sheltered and undemanding tradition of the prosperous Church of England.

The Doughtys of Suffolk had built up extensive lands over the centuries, and occupied a succession of livings; Frederica’s relatives, the Hothams of East Yorkshire, had produced six admirals, three generals, a bishop, a judge and a colonial governor. It was a family that drank in unquestioning patriotism and the peculiarly restrained devotion of the Established Church with its mother’s milk – the sort of family on which the empire had relied for generations.

But it seems, too, to have been a family where the idea of pride and duty replaced any open show of affection. Doughty’s cousin, the Rear-Admiral Frederick Proby Doughty who now lies in Martlesham churchyard, wrote a journal in which he recorded his memories of the various members of his family – and on the Doughtys’ side at least, there does not seem to have been much obvious emotional closeness. ‘We were badly off as children in the matter of relatives – no grandfathers or grandmothers, or relatives that were disposed to do the correct and orthodox “uncle and aunt” business.’6 The family would perhaps have been scandalized not to be considered ‘correct and orthodox’, but the message is clear. Of his uncle, the late father of young Charles and Henry, he reminisced: ‘I do not recall much connected with him, except on one occasion when walking with my father at Martlesham. I suppose I was rather busy with my tongue – he said to my father, “Why do you allow that boy to go on chattering? Box his ears …!”’

And there was more for the young Charles Doughty to contend with than the occasional bad temper of a crusty old Victorian clergy man. For all his wealth, Doughty’s father was stretching himself financially, with an ambitious programme of ostentatious building works at Theberton Hall. It seems to have been something of a family failing – only a few years later, after a similar programme of grandiose ‘improvements’, Doughty’s uncle, Frederick Goodwin Doughty, was forced to put his own home of Martlesham Hall, a few miles away, up for sale.

The boys, no doubt, were too young to be aware of the growing problems, but the atmosphere at Theberton Hall cannot have been a happy one. Their father seems to have been shattered by the untimely death of his ‘late dear wife’, who was only thirty-five when she died. No doubt the young Charles was not the only one to feel a sense of loss and bereavement: his father’s own health was not strong, and on 6 April 1850 he put his affairs in order, writing a new will, with an instruction that he should be buried next to Frederica in Theberton Church. Less than three weeks later he was dead, at the age of fifty-two, the doctors giving the cause of death as ‘Exhausted nature following a severe bilious attack’. The two boys were now orphans.

Childhood, it must have seemed, was little more than a harsh preparation for a life of loneliness. Theberton Hall was shut up, and within a few weeks the auctioneers moved in. At 11 a.m. on 28 August they started their sale with Lot 1 – two brown bread pans, a strainer and three baking pans – and over the next four days sold off the entire contents of the house. The Reverend Doughty’s fine wine cellar and his extensive library were split up and put under the hammer; so were his ‘town-built chariot’ and his single-horse phaeton. Even more distressing for the two boys, everything in their nursery was sold – brass mounted fender, fire-irons and pictures off the wall. It was a common practice in the mid nineteenth century to sell off the belongings of the dead – but that made it no less heart-rending for the young boys, who had to see what had once been their home broken up and carried off by strangers.

But if the seeds of Doughty’s later emotional detachment and determined self-sufficiency can be seen in these bleak years of bereavement, there were other members of his immediate family with a brisker, no-nonsense attitude to death. Frederick Proby Doughty’s detached account of his uncle’s financial problems and death seems brutal today, but it probably reflects the severely practical attitude of the family at large.

He had commenced great alterations to Theberton Hall, building enormous stablings, altering the entrance, building a picture gallery, and other expensive undertakings far beyond his means, and out of character with such an estate. Luckily he died, leaving his sons Henry and Charles … a long minority before them to recover and pull through the expenses and debts their father had incurred.

In fact, if his will is anything to go by, Charles Doughty senior still had plenty to leave his two sons. For Henry, there were several houses and estates spread over various parishes in Suffolk – among them Theberton Hall itself.

Charles, as the younger son, was less generously provided for, but he still inherited three farms, all his father’s government funds and securities, and an unspecified amount of cash, annuities and other investments which derived originally from the Hotham family. His guardian was to be his uncle, Frederick Doughty of Martlesham, father of the journal-keeping Frederick Proby Doughty – but the journal gives little cause to suggest that the move to Martlesham brought any fresh lightheartedness or fun into the little boy’s life. The elderly admiral recalled later: ‘I never remember a guest staying in the house, and but one or two dinner parties; and visiting friends were few and far distant.’ Of his mother – the woman who was to share the job of bringing up the young Charles Doughty – he wrote: ‘I fancy she was very delicate – lived mostly when at home stretched out on a sofa. I don’t remember her ever entering into any games or sports with us …’ She had a good education and spoke several languages, but she wasn’t known for her friendliness. ‘Extreme amiability’, her son noted carefully, ‘was never one of my mother’s vices or virtues.’