Полная версия:

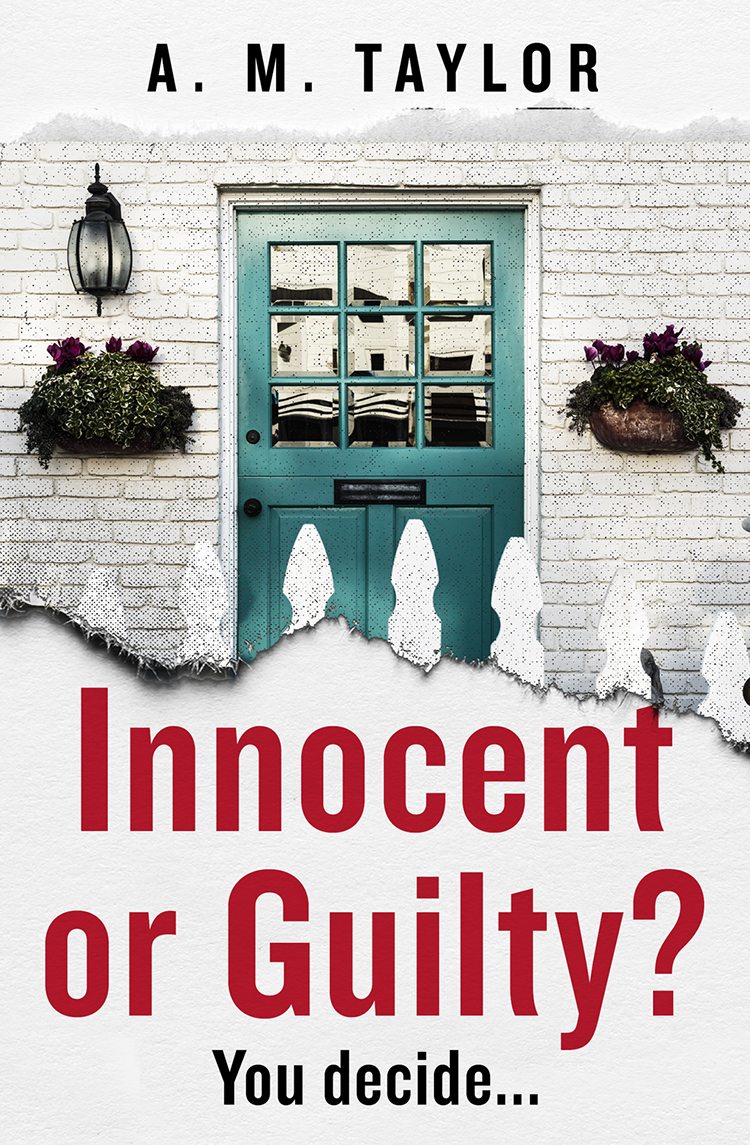

Innocent or Guilty?

Innocent or Guilty?

A. M. TAYLOR

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk

One More Chapter

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Annie Taylor 2019

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Annie Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2019 ISBN: 9780008312930

Version: 2019-08-23

For my parents

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1. Then

Chapter 2. Now

Chapter 3. Then

Chapter 4. Now

Chapter 5. Then

Chapter 6. Now

Chapter 7. Then

Chapter 8. Now

Chapter 9. Then

Chapter 10. Now

Chapter 11. Then

Chapter 12. Now

Chapter 13. Then

Chapter 14. Now

Chapter 15. Then

Chapter 16. Now

Chapter 17. Then

Chapter 18. Now

Chapter 19. Then

Chapter 20. Now

Chapter 21. Then

Chapter 22. Now

Chapter 23. Then

Chapter 24. Now

Chapter 25. Then

Chapter 26. Now

Chapter 27. Then

Chapter 28. Now

Chapter 29. Then

Chapter 30. Now

Chapter 31. Then

Chapter 32. Now

Chapter 33. Then

Chapter 34. Now

Chapter 35. Then

Chapter 36. Now

Chapter 37. Then

Chapter 38. Now

Chapter 39. Then

Chapter 40. Now

Chapter 41. Then

Chapter 42. Now

Chapter 43. Then

Chapter 44. Now

Chapter 45. Then

Chapter 46. Now

Chapter 47. Then

Chapter 48. Now

Chapter 49. Six Weeks Later

Chapter 50. That Night

Chapter 51. Now

Keep Reading …

Acknowledgements

Also by A. M. Taylor

About the Author

About the Publisher

1.

THEN

They find the body on a Sunday.

He didn’t return home the night before, which isn’t unheard of, but when he doesn’t make it back in time for church and he still isn’t home by the time they return, the family begins to worry. His mother rings the police and they tell her to sit tight, while his father calls his brother and gathers up a few of the boy’s friends to set up a search party.

He’s lying in the woods.

He has been all night.

He’s face down in the mud. There’s blood on the side and the back of his head, matting down his hair, pressing it to his skull. It’s a friend who finds him, calling out for the boy’s dad when he does so, the father running wildly towards him, pushing him out of the way, slipping in the mud.

He makes the mistake of moving him. Grabbing him by the shoulders to shake him awake in desperation. When he pulls his hands away they’re covered in blood and as the stories soon will go, the father screams, grief curdling at his throat. The police are called again and this time they come, sirens wailing on the damp air, a parent’s desperate call. Friends and family are pushed to the side lines, forced to watch as the routines of a crime scene establish themselves and the detectives take statements, waiting for the medical examiner to arrive.

The boy’s uncle is sent back to the house with a female police officer in tow to break the news to the mother. Neighbors will go on to tell other neighbors about how she answers the door, arm outstretched, finger pointing at her brother-in-law’s broken face as she shouts “No, no, no, no, no,” over and over and over again, until the female police officer wraps her arms around the older woman’s shaking shoulders and draws her inside her own home.

Word spreads, text messages sent, phone calls answered, whispers met by gasps, grimaces of shock followed by the promise of tears.

Tyler Washington is dead they’re saying.

Murdered.

Found in the woods with his skull bashed in.

Less than a week later my twin brother is arrested.

My brother was born eleven minutes and 37 seconds after me. It was an easy delivery for twins apparently, or so our mom always told us. We were her second pregnancy, and we practically slipped right out; she and Dad barely making it to the hospital before I made my appearance. I came screaming into the world, face red and pink and white, covered in blood and placenta, all of it quickly wiped away to make me clean. Ethan slipped out silently though; maybe I was taking up all the oxygen in the room. In the womb. But Mom says the nurse just gave him a little slap on his small round bottom and he joined me in my new-to-the-world screams.

Twins.

Mom says she was terrified to begin with. Not just of how much more work and effort was involved but with how different we were from our sister Georgia. We took up twice the space, twice the time, twice the breast milk, twice the effort, but we were also strangely self-sufficient she’d tell us. She felt superfluous, she said. Our older sister Georgia had needed her, wanted her, all the time. We needed her occasionally, and wanted only each other. But that was a long time ago and by the time Ethan is arrested we barely speak to one another. Sometimes, I like to tell myself that it’s because we don’t need to; we already know what the other is thinking. But it’s not like that. We shared a womb, shared a life and then suddenly, we split. Into two different people and the difference was what we needed to make us two different people. Otherwise we’d have just spent the rest of our lives as ‘the twins’.

But instead what happened was that Ethan became my twin. I was Olivia, and Ethan was ‘Olivia’s twin’.

Until the Sunday when Tyler’s body is found.

Until the Friday, just under a week later when Ethan is arrested for Tyler Washington’s murder, and I become, forever, irrevocably, impossibly ‘Ethan Hall’s twin sister’.

2.

NOW

“There’s no way she did it,” Matt said, “no fucking way.”

“Why?” I asked, “Because she’s a cute girl you wanna screw?”

Matt’s pale face pinkened ever so slightly, those promising rosy spots deepening on the apple of his cheeks. He avoided my gaze when he said, “No, man. She’s just so … small. And quiet. She’s not the type.”

“It’s never the type in these situations though, is it?” Daniel said, voice creamy and languorous, sliding his eyes towards me, glowing in the artificially lit room. It was dark outside already, the blank slate of a grey Oregon afternoon overcrowding the room, so we’d had to turn the ugly strip lights on even though it wasn’t yet four in the afternoon. We’d been in the same room for hours, lunch detritus littering the table, the air pungent with uneaten sandwiches and cold coffee. Tempers and nerves were starting to fray, impatience climbing the walls. I loved this part though; when it felt like anything could happen, like there was no way we could ever lose, like justice wasn’t a pendulum that could sway either way but a judge’s righteous gavel just waiting to be knocked on wood, the sound echoing around the room. We were doing background research on the firm’s newest client Reid Murphy, and the man she’d been accused of almost killing, James Asher, who was currently in a coma on an intensive care ward on the other side of the city. Murphy was 22 and looked even younger, so young you’d ask if her parents were home if she answered her own front door. And Matt was right; she was small and quiet, scared to death in my opinion, not that my opinion really mattered here. All of it would help though; the jury bench packed full of people like my colleagues who thought a girl like Reid Murphy couldn’t ever possibly hurt a man so badly she put him in a coma. But I’d seen something in the un-seeing stare of her eyes, the unwavering gaze, and I wasn’t so sure. Anyone’s capable of anything in my opinion. Again, not that it mattered, not that my opinion counted for anything; we were here to prove she was innocent whether she was or not.

We’d reached the ropiest part of the day, when we’d all been there too long: lunch had been eaten and we’d all start thinking about dinner soon, but for now it was the lull and the dip of late afternoon. Distraction roaring in, heads up, eyes darting between me and Matt, opinions readied to be lobbed across the conference room table. I looked across to Daniel, and could see that his eyes were dancing, like always, ready to tease and tickle, the facetious little quirk to his eyebrows getting more and more pronounced.

Daniel caught my eye and widened his, about to say something, mouth opening to a cartoonish ‘o’ when his phone began to vibrate and his forehead creased. He made the sign for ‘one moment’ at me, holding his finger in the air, and the groans began before he was even out the door. “You better be coming straight back, Koh!” Matt called after him, the glass door closing noiselessly on Daniel’s retreating back. “That better have been some medical results,” Matt continued to grumble, and I thought, not for the first time, about how quickly we’d all become exactly who and what the firm’s partners wanted us to become. Snipping and sniping and picking each other off, one by one. It was all happy and good natured until someone looked as though they weren’t pulling their weight, and suddenly the jabs had real force behind them and judgment started to crash the party. The best of friends, right up until we weren’t.

Daniel’s departure dampened the mood and a weight settled over the room. Instead of punchy and worked up, we fell into resigned lethargy, bending our heads down again, hard at work. Daniel was gone a while though, and my eyes had started to swim, desperate for more caffeine when he eventually came back. No one said anything to him when he did, but he was waiting for me when we finally left the conference room several hours later. He had been sat closest to the door and I furthest from it, so everyone filed out ahead of me, Daniel leaning against the hallway wall, waiting. “What’s going on?” I asked, shouldering my bag, adjusting my jacket. He had a look on his face I couldn’t quite decipher, maybe it was anticipation.

“That phone call was from my friend Ray, you know, the one who works on that podcast?”

“The true crime podcast? Why, was he asking for your help?” We might have only been first year associates, but we were working for one of the biggest criminal defense law firms in Portland, so a true crime podcast producer coming to Daniel for his expertise or opinion wasn’t completely outside the realm of possibilities.

“No, he’s here in Portland, with the host, Kat.”

“Are they working on a Portland case?” I asked, interest creeping into my voice despite myself.

“Maybe, yeah. I told them about you. And Ethan. They’re thinking about doing his case.”

I couldn’t say anything for a second, my mouth suddenly dry. When I eventually managed to speak it came out as a croak, “What?”

“Yeah, I emailed him about it ages ago, but they were just wrapping up the last season and wanted to do a little research, look around a little before deciding on their next topic.” He was bouncing on the balls of his feet, his face lively, animated; eyebrows up by his hairline, mouth grinning and winning.

“Why did you email him in the first place, though? I didn’t ask you to do that,” I said, my mouth still dry, desperate for a drink.

“No, I know. Do I need your permission for everything?”

“When it comes to my fucking family, yeah you do.”

Daniel’s body stopped moving, his never-ending energy finally brought to a standstill. “Liv, come on, what’s the problem here? This is a good thing. It could be really good; the first case they worked on the sentence got overturned, and the guy from the second season? He’s just filed for a retrial, and finally got his request granted after years of trying.”

My hands went up to the strap of my bag, fiddling with it, the weight suddenly uncomfortable on my shoulder. I didn’t meet Daniel’s eye when I said, “It’s just not your place. What were you thinking? How could you do this and not tell me?”

“I’m telling you now,” he said, the words expelled on a massive exhale of breath. “Plus, it’s not as if it’s all set in stone yet. Kat wants to meet you and Ethan, get to know you and the case a little better.”

“What?” I said again, this time in a snap, “Me and Ethan?”

“Yeah, they like to work on cases where they can have the involvement of the family and a close relationship with the subject. You’ve listened to the podcast, you know that.”

I shook my head, but once again I couldn’t say anything, my mind a blank trap. Daniel reached out and put his hand on my shoulder, it was warm and heavy like it always was, a tiny reverberation thrumming through me as he said in a low voice, “Look, I’ve said we’ll meet them for a drink at Blue Plate, and that’s all it has to be if you want. A no-strings after work drink with an old friend of mine. That’s it.”

I knew that wouldn’t be it, but I finally looked him in the eye, and even though I knew exactly what he was doing, the calm, convincing tone, the comforting touch, I nodded my head and agreed to something that made the pit of my stomach scramble and lurch.

Blue Plate was busy and I couldn’t see my roommate Samira anywhere. Probably she was back in the kitchen, prepping the desserts that helped make the restaurant so popular. The maȋtre d’ greeted me and Daniel with familiarity and gave us a corner seat in one of their coveted forest green leather booths. Being roommates with the pastry chef had its perks. Ray and Kat hadn’t arrived yet, and this bothered me. I hadn’t wanted to come after all, hadn’t even known it was happening until roughly twenty minutes ago, and now here I was waiting on a couple of strangers. The restaurant was moodily lit, glittering candles, spherical sconces emitting a gas like low glow. The couple at the table right in front of us were on a first or second date, and to the left a large party had gathered to celebrate a birthday. The birthday girl had balloons tied to the back of her chair and the party’s laughter spilled out over the whole restaurant, people turning to look. I fiddled with my cutlery, the table all laid up for us to eat although we hadn’t ordered any food yet – just wine. I jiggled my legs up and down under the table, Daniel eventually moving his hand to my left knee to still it.

“What is wrong with you?” he said while pouring me a glass of wine. There wasn’t any accusation in his voice; he was practically laughing and he gave me a sidelong look that seemed to say ‘who are you?’

“I’m nervous,” I answered.

“I guess I’ve never seen you nervous.”

“I guess not.”

“You don’t have to worry, Liv. They’re not banking on this for their next season, I’m pretty sure they’ve got other options, so if you don’t want to do it, you don’t want to do it.”

“You think I should though,” I said, taking a large gulp of wine, wishing there was bread on the table for me to bite down on.

Daniel shrugged, “I just think … what have you got to lose?”

I looked at him, wondering. I guess he would think that.

“Hey,” he said suddenly, breaking eye contact with me, and moving to stand up although the table stopped him from doing so properly, so he was kind of crouching, hovering over the table, waving an arm in the air, “there they are! Ray! Over here, man.” He was waving them towards us, ushering with his long, outstretched arm, and I watched as two people walked towards us, weaving their way around tables and chairs.

Ray was shorter than I’d expected, but then everyone is normally shorter than I expected. Kat, meanwhile – for I had to assume this was Kat – was over six feet tall, wearing a mustard yellow shearling biker jacket that matched the wrap she had on her head hiding her hair. Underneath the jacket, she was wearing a black and dark green leopard print jumpsuit, and her shoes were stacked high, not that she needed the extra height, chunky soled Chelsea boots protecting her feet from the rain outside. She smiled amiably at us both as introductions were made. I reached my hand across the table to shake hers, and her smile grew wider, “Hi, Olivia. It’s really nice to meet you.” Her voice was low and throaty, a little scratched, and immediately familiar after hours of listening to her on the podcast.

I nodded in response, and felt my throat constrict. Daniel had to nudge me a little to remind me to speak and I was relieved my voice came out sounding normal when I said, “Yeah, you too. Both of you,” I added, taking in Ray as well. “I’m a big fan of the podcast.”

“Oh, you listen? I wasn’t sure after speaking to Danny about it,” Ray said.

I raised my eyebrows at the ‘Danny’, but nodded again, “No, I listen. I just didn’t ever expect to be the subject of it.”

Kat and Ray shared a small look and Kat said, “Well, we haven’t decided on the topic for our third season yet, to be honest. And it would really be Ethan rather than you that was the subject …” she finished with a grin, stretching her hand out to take the glass of wine Daniel had just poured for her.

“Oh, I know it wouldn’t be me,” I said, taking a deep breath, “I just meant … this was hard for my whole family, you know? It’s not just Ethan, although obviously it’s his story. He is the one in prison, after all.”

Kat raised both her eyebrows at me and nodded slowly. “Do you think you’d be able to get your family to talk with us? If we moved forward with Ethan’s story?”

I licked my lips, trying to stop myself from biting at them. “Maybe, I don’t know. Probably Georgia, my sister, but even then I’m not completely sure.”

“But, they do believe he’s innocent, right? Like you do?” Kat asked.

And there it was; Ethan’s innocence, dropping into the room like a rock through water.

“Yes,” I said eventually, but it was so long since I’d talked to my family about Ethan and his innocence, I wasn’t completely sure whether I’d just told a lie or not.

3.

THEN

The room changes the moment the judge says the word, ‘guilty’. I watch Ethan’s shoulders stiffen, his entire body braced. We were told to expect this, and yet still, somehow, I didn’t. Didn’t think the system could get it this wrong. Ethan’s long, slim body is completely still; he hasn’t moved, but his lawyer is next to him, arm slung around his shoulders, and I wish I could hear what he’s saying but I can’t. Ethan still doesn’t move. Doesn’t make to reply to his lawyer, doesn’t look as though he’s ever going to move again, until suddenly he does. He’s forced to; the bailiff is attaching his handcuffs again, taking him away.

He turns then, finally, and even though Mom calls out his name, her voice cracking the room in two, he looks straight at me, our identical eyes catching. We’re the same height. He’s not all that tall for a guy, but for a girl I am, and so we’re eye to eye. Mom reaches up to him, pulling him into a hug before they take him away, and Dad has to pull her from him, letting my older sister, Georgia in for a hug too, and then clapping Ethan’s shoulder. Dad says something I don’t hear, and Ethan is swaying slightly in the push and pull, arms and hands outstretched towards him, taking, taking, taking. And still he hasn’t taken his eyes off mine. Finally we hug, for the first time in years it feels like, and of course it’s only one sided because he’s already in chains, but before he’s pulled away again I say, “I’ll make this right, okay? I promise.”

He nods at me, as if it’s all understood, a done deal, as if he knows that, somehow, someday, I’ll get him out of this, out of prison, even though I have no idea how, and wish that he’d tell me. Mom and Georgia are crying, albeit quietly, as Ethan is led away, and when I turn to look at Dad, he’s dumbfounded, his face a mask of stupefied tragedy like I’ve never seen it before. I want to reach out to all of them, to be pulled back into their orbit, but I feel detached from them now, a satellite circling them, no longer a part of the home planet. Mom and Georgia look so similar huddled together, the same size and shape, small and compact, shoulder to shoulder. Ethan and I always took after Dad more, and when I look at him now I wonder if I’m seeing my twin in thirty years’ time, face crumpled and destroyed by sudden loss, transfixed by a horror no one ever saw coming. And then I make a decision, putting my arms around them all, pulling them towards me, pulling them into my own tilted orbit; the strange, circling satellite, and like that we walk out of the courtroom together.

4.

NOW

“Did you ever doubt him?” Kat asked, swirling the wine in her glass around so it shone in the candlelight. “Did you ever think he might have done it?”

“No,” I said.

“Really?” She said, her head pulled back in surprise, her voice going up. “Not even once?”

“We shared a womb. It breeds a certain amount of trust.”

“So, you guys are like, really close?”

I took a sip of wine, licking my lips after, “We weren’t when it all happened … when Tyler died, we hadn’t been close for years, not since we were nine, ten.”

“Why?”

I shrugged, trying to think back that far. It had all seemed so important then. “We were just really different. We still are.”

“But you’re close now?” Kat was leaning forward, her arms resting on the table. It felt casual, but it wasn’t and I wondered for a second if she was recording the whole thing.

“It’s a little difficult to be close when there’s an entire prison system between you, but yeah, I guess you’d say we were close.”

“I’d really like to meet him. To go and see him, but I don’t think he’ll see me without you there.”