Полная версия:

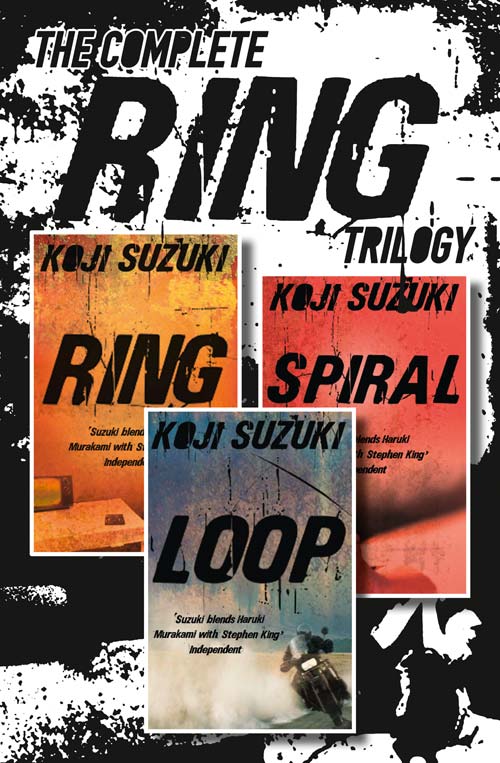

The Complete Ring Trilogy: Ring, Spiral, Loop

KOJI SUZUKI

THE COMPLETE RING TRILOGY

Ring Spiral Loop

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Ring

Copyright © Koji Suzuki 2003

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2004,

First published in the USA by Vertical, Inc 2003,

Originally published in Japan as Ringu by Kadokawa Shoten, Tokyo, 1991

Cover photograph/illustration © Ghislain & Marie David de Lossy/Getty Images

Spiral

Copyright © Koji Suzuki 2004

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005,

First published in the USA by Vertical, Inc 2004,

Originally published in Japan as Rasen by Kadokawa Shoten, Tokyo, 1995

Cover photograph © pierre d’alancaisez/Alamy

Loop

Copyright © Koji Suzuki 2005

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2006,

First published in the USA by Vertical, Inc 2005,

Originally published in Japan as Rupu by Kadokawa Shoten, Tokyo, 1998

Cover photographs © Sean Murphy/Getty Images (dust cloud); Karl Weather/Getty Images (motorcycle).

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2007

Koji Suzuki asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBNs:

Ring: 9780007331574 Spiral: 9780007331581 Loop: 9780007331598

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2015 ISBN: 9780008121815

Version: 2016-12-14

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Ring

Spiral

Loop

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

RING

KOJI SUZUKI

Translation

Robert B. Rohmer

Glynne Walley

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Part One: Autumn

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part Two: Highlands

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part Three: Gusts

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part Four: Ripples

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

1

September 5, 1990, 10:49 pm, Yokohama

A row of condominium buildings, each fourteen stories high, ran along the northern edge of the housing development next to the Sankeien garden. Although built only recently, nearly all the units were occupied. Nearly a hundred dwellings were crammed into each building, but most of the inhabitants had never even seen the faces of their neighbors. The only proof that people lived here came at night, when windows lit up.

Off to the south the oily surface of the ocean reflected the glittering lights of a factory. A maze of pipes and conduits crawled along the factory walls like blood vessels on muscle tissue. Countless lights played over the front wall of the factory like insects that glow in the dark; even this grotesque scene had a certain type of beauty. The factory cast a wordless shadow on the black sea beyond.

A few hundred meters closer, in the housing development, a single new two-story home stood among empty lots spaced at precise intervals. Its front door opened directly onto the street, which ran north and south, and beside it was a one-car garage. The home was ordinary, like those found in any new housing development anywhere, but there were no other houses behind or beside it. Perhaps owing to their inconvenience for transport links, few of the lots had been sold, and For Sale signs could be seen here and there all along the street. Compared to the condos, which were completed at about the same time and which were immediately snapped up by buyers, the housing development looked quite lonely.

A beam of fluorescent light fell from an open window on the second floor of the house onto the dark surface of the street below. The light, the only one in the house, came from the room of Tomoko Oishi. Dressed in shorts and a white T-shirt, she was slouched in a chair reading a book for school; her body was twisted into an impossible position, legs stretched out toward an electric fan on the floor. Fanning herself with the hem of her T-shirt to allow the breeze to hit her bare flesh, she muttered about the heat to no one in particular. A senior at a private girls’ high school, she had let her homework pile up over the summer vacation; she had played too much, and she blamed it on the heat. The summer, however, hadn’t really been all that hot. There hadn’t been many clear days, and she hadn’t been able to spend nearly as much time at the beach as she did most summers. And what’s more, as soon as vacation was over, there were five straight days of perfect summer weather. It irritated Tomoko: she resented the clear sky.

How was she supposed to study in this stupid heat?

With the hand she had been running through her hair Tomoko reached over to turn up the volume of the radio. She saw a moth alight on the window screen beside her, then fly away somewhere, blown by the wind from the fan. The screen trembled slightly for a moment after the bug had vanished into the darkness.

She had a test tomorrow, but she was getting nowhere. Tomoko Oishi wasn’t going to be ready for it even if she pulled an all-nighter.

She looked at the clock. Almost eleven. She thought of watching the day’s baseball wrap-up on TV. Maybe she’d catch a glimpse of her parents in the infield seats. But Tomoko, who desperately wanted to get into college, was worried about the test. All she had to do was get into college. It didn’t matter where, as long as it was a college. Even then, what an unfulfilling summer vacation it had been! The foul weather had kept her from having any real fun, while the oppressive humidity had kept her from getting any work done.

It was my last summer in high school. I wanted to go out with a bang and now it’s all over. The end.

Her mind strayed to a meatier target than the weather to vent her bad mood on.

And what’s with Mom and Dad anyway? Leaving their daughter all alone studying like this, covered in sweat, while they go gallivanting out to a ball game. Why don’t they think about my feelings for a change?

Someone at work had unexpectedly given her father a pair of tickets to the Giants game, and so her parents had gone to Tokyo Dome. By now it was almost time for them to be getting home, unless they’d gone out somewhere after the game. For the moment Tomoko was home alone in their brand-new house.

It was strangely humid, considering that it hadn’t rained in several days. In addition to the perspiration that oozed from her body, a dampness seemed to hang in the air. Tomoko unconsciously slapped at her thigh. But when she moved her hand away she could find no trace of the mosquito. An itch began to develop just above her knee, but maybe it was just her imagination. She heard a buzzing sound. Tomoko waved her hands over her head. A fly. It flew suddenly upwards to escape the draft from the fan and disappeared from view. How had a fly got into the room? The door was closed. Tomoko checked the window screens, but nowhere could she find a hole big enough to admit a fly. She suddenly realized she was thirsty. She also needed to pee.

She felt stifled—not exactly like she was suffocating, but like there was a weight pressing down on her chest. For some time Tomoko had been complaining to herself about how unfair life was, but now she was like a different person as she lapsed into silence. As she started down the stairs her heart began to pound for no reason. Headlights from a passing car grazed across the wall at the foot of the stairs and slipped away. As the sound of the car’s engine faded into the distance, the darkness in the house seemed to grow more intense. Tomoko intentionally made a lot of noise going down the stairs and turned on the light in the downstairs hall.

She remained seated on the toilet, lost in thought, for a long time even after she had finished peeing. The violent beating of her heart still had not subsided. She’d never experienced anything like this before. What was going on? She took several deep breaths to steady herself, then stood up and pulled up her shorts and panties together.

Mom and Dad, please get home soon, she said to herself, suddenly sounding very girlish. Eww, gross. Who am I talking to?

It wasn’t like she was addressing her parents, asking them to come home. She was asking someone else …

Hey. Stop scaring me. Please …

Before she knew it she was even asking politely.

She washed her hands at the kitchen sink. Without drying them she took some ice cubes from the freezer, dropped them in a glass, and filled it with coke. She drained the glass in a single gulp and set it on the counter. The ice cubes swirled in the glass for a moment, then settled. Tomoko shivered. She felt cold. Her throat was still dry. She took the big bottle of coke from the refrigerator and refilled her glass. Her hands were shaking now. She had a feeling there was something behind her. Some thing—definitely not a person. The sour stench of rotting flesh melted into the air around her, enveloping her. It couldn’t be anything corporeal.

“Stop it! Please!” she begged, speaking aloud now.

The fifteen-watt fluorescent bulb over the kitchen sink flickered on and off like ragged breathing. It had to be new, but its light seemed pretty unreliable right now. Suddenly Tomoko wished she had hit the switch that turned on all the lights in the kitchen. But she couldn’t walk over to where the switch was. She couldn’t even turn around. She knew what was behind her: a Japanese-style room of eight tatami mats, with the Buddhist altar dedicated to her grandfather’s memory in the alcove. Through the slightly open curtains she’d be able to see the grass in the empty lots and a thin stripe of light from the condos beyond. There shouldn’t be anything else.

By the time she had drunk half the second glass of cola, Tomoko couldn’t move at all. The feeling was too intense, she couldn’t be just imagining the presence. She was sure that something was reaching out even now to touch her on the neck.

What if it’s …? She didn’t want to think the rest. If she did, if she went on like that, she’d remember, and she didn’t think she could stand the terror. It had happened a week ago, so long ago she’d forgotten. It was all Shuichi’s fault—he shouldn’t have said that … Later, none of them could stop. But then they’d come back to the city and those scenes, those vivid images, hadn’t seemed quite as believable. The whole thing had just been someone’s idea of a joke. Tomoko tried to think about something more cheerful. Anything besides that. But if it was … If that had been real … after all, the phone did ring, didn’t it?

… Oh, Mom and Dad, what are you doing?

“Come home!” Tomoko cried aloud.

But even after she spoke, the eerie shadow showed no signs of dissipating. It was behind her, keeping still, watching and waiting. Waiting for its chance to arrive.

At seventeen Tomoko didn’t know what true terror was. But she did know that there were fears that grew in the imagination of their own accord. That must be it. Yeah, that’s all it is. When I turn around there won’t be anything there. Nothing at all.

Tomoko was seized by a desire to turn around. She wanted to confirm that there was nothing there and get herself out of the situation. But was that really all there was to it? An evil chill seemed to rise up around her shoulders, spread to her back, and began to slither down her spine, lower and lower. Her T-shirt was soaked with cold sweat. Her physical responses were too strong for it to be just her imagination.

… Didn’t someone say your body is more honest than your mind?

Yet, another voice spoke too: Turn around, there shouldn’t be anything there. If you don’t finish your coke and get back to your studies there’s no telling how you’ll do on the test tomorrow.

In the glass an ice cube cracked. As if spurred by the sound, without stopping to think, Tomoko spun around.

September 5, 10:54 pm

Tokyo, the intersection in front of Shinagawa Station The light turned yellow right in front of him. He could have darted through, but instead Kimura pulled his cab over to the curb. He was hoping to pick up a fare headed for Roppongi Crossing; a lot of customers he picked up here were bound for Akasaka or Roppongi, and it wasn’t uncommon for people to jump in while he was stopped at a light like this.

A motorcycle nosed up between Kimura’s taxi and the curb and came to a stop just at the edge of the crossing. The rider was a young man dressed in jeans. Kimura got annoyed by motorcycles, the way they wove and darted their way through traffic like this. He especially hated it when he was waiting at a light and a bike came up and stopped right by his door, blocking it. And today, he had been hassled by customers all day long and was in a foul mood. Kimura cast a sour look at the biker. His face was hidden by his helmet visor. One leg rested on the curb of the sidewalk, his knees were spread wide, and he rocked his body back and forth in a thoroughly slovenly manner.

A young lady with nice legs walked by on the sidewalk. The biker turned his head to watch her go by. But his gaze didn’t follow her the whole way. His head had swiveled about 90 degrees when he seemed to fix his gaze on the show window behind her. The woman walked on out of his field of vision. The biker was left behind, staring intently at something. The “walk” light began to flash and then went out. Pedestrians caught in the middle of the street began to hurry, crossing right in front of the taxi. Nobody raised a hand or headed for his cab. Kimura revved the engine and waited for the light to turn green.

Just then the biker seemed to be seized by a great spasm, raising both arms and collapsing against Kimura’s taxi. He fell against the door of the cab with a loud thump and disappeared from view.

You asshole.

The kid must’ve lost his balance and fallen over, thought Kimura as he turned on his blinkers and got out of the car. If the door was damaged, he intended to make the kid pay for repairs. The light turned green and the cars behind Kimura’s began to pass by into the intersection. The biker was lying face up on the street, thrashing his legs and struggling with both hands to remove his helmet. Before checking out the kid, though, Kimura first looked at his meal ticket. Just as he had expected, there was a long, angling crease in the door panel.

“Shit!” Kimura clicked his tongue in disgust as he approached the fallen man. Despite the fact that the strap was still securely fastened under his chin, the guy was desperately trying to remove his helmet—he seemed ready to rip his own head off in the process.

Does it hurt that bad?

Kimura realized now that something was seriously wrong with the rider. He finally squatted down next to him and asked, “You all right?” Because of the tinted visor he couldn’t makeout the man’s expression. The biker clutched at Kimura’s hand and seemed to be begging for something. He was almost clinging to Kimura. He said nothing. He didn’t try to raise the visor. Kimura jumped to action.

“Hold on, I’ll call an ambulance.”

Running to a public telephone, Kimura puzzled over how a simple fall from a standing position could have turned into this. He must have hit his head just right.

But don’t be stupid. The idiot was wearing a helmet, right? He doesn’t look like he broke an arm or a leg. I hope this doesn’t turn into a pain in the ass … It wouldn’t be too good for me if he hurt himself running into my car.

Kimura had a bad feeling about this.

So if he really is hurt, does it come out of my insurance? That means an accident report, which means the cops …

When he hung up and went back, the man was lying unmoving with his hands clutching his throat. Several passers-by had stopped and were looking on with concerned expressions. Kimura pushed his way through the people, making sure everybody knew it had been he who had called the ambulance.

“Hey! Hey! Hang in there. The ambulance is on its way.” Kimura unfastened the chin strap of the helmet. It came right off: Kimura couldn’t believe how the guy had been struggling with it earlier. The man’s face was amazingly distorted. The only word that could describe his expression was astonishment. Both eyes were wide open and staring and his bright-red tongue was stuck in the back of his throat, blocking it, while saliva drooled from the corner of his mouth. The ambulance would be arriving too late. When his hands had touched the kid’s throat in removing his helmet, he hadn’t felt a pulse. Kimura shuddered. The scene was losing reality.

One wheel of the fallen motorcycle still spun slowly and oil leaked from the engine, pooling in the street and running into the sewer. There was no breeze. The night sky was clear, while directly over their heads the stoplight turned red again. Kimura rose shakily to his feet, clutching at the guardrail that ran along the sidewalk. From there he looked once more at the man lying in the street. The man’s head, pillowed on his helmet, was bent at nearly a right angle. An unnatural posture no matter how you looked at it.

Did I put it there? Did I put his head on his helmet like that? Like a pillow? For what?

He couldn’t recall the past several seconds. Those wide-open eyes were looking at him. A sinister chill swept over him. Lukewarm air seemed to pass right over his shoulders. It was a tropical evening, but Kimura found himself shivering uncontrollably.

2

The early morning light of autumn reflected off the green surface of the inner moat of the Imperial Palace. September’s stifling heat was finally fading. Kazuyuki Asakawa was halfway down to the subway platform, but suddenly had a change of heart: he wanted a closer look at the water he’d been looking at from the ninth floor. It felt like the filthy air of the editorial offices had filtered down here to the basement levels like dregs settling to the bottom of a bottle: he wanted to breathe outside air. He climbed the stairs to the street. With the green of the palace grounds in front of him, the exhaust fumes generated from the confluence of the No. 5 Expressway and the Ring Road didn’t seem so noxious. The brightening sky shone in the cool of the morning.

Asakawa was physically fatigued from having worked all night, but he wasn’t especially sleepy. The fact that he’d completed his article stimulated him and kept his brain cells active. He hadn’t taken a day off for two weeks, and planned to spend today and tomorrow at home, resting up. He was just going to take it easy—on orders from the editor-in-chief.

He saw an empty taxi coming from the direction of Kudanshita, and he instinctively raised his hand. Two days ago his subway commuter pass from Takebashi to Shinbaba had expired, and he hadn’t bought a new one yet. It cost four hundred yen to get to his condominium in Kita Shinagawa from here by subway, while it cost nearly two thousand yen to go by cab. He hated to waste over fifteen hundred yen, but when he thought of the three transfers he’d have to make on the subway, and the fact that he’d just gotten paid, he decided he could splurge just this once.

Asakawa’s decision to take a taxi on this day and at this spot was nothing more than a whim, the outcome of a series of innocuous impulses. He hadn’t emerged from the subway with the intention of hailing a cab. He’d been seduced by the outside air at the very moment that a taxi had approached with its red “vacant” lamp lit, and in that instant the thought of buying a ticket and transferring through three separate stations seemed like more effort than he could stand. If he had taken the subway home, however, a certain pair of incidents would almost certainly never have been connected. Of course, a story always begins with such a coincidence.

The taxi pulled to a hesitant stop in front of the Palaceside Building. The driver was a small man of about forty, and it looked like he too had been up all night, his eyes were so red. There was a color mug shot on the dashboard with the driver’s name, Mikio Kimura, written beside it.

“Kita Shinagawa, please.”

Hearing the destination, Kimura felt like doing a little dance. Kita Shinagawa was just past his company’s garage in Higashi Gotanda, and since it was the end of his shift, he was planning to go in that direction anyway. Moments like this, when he guessed right and things went his way, reminded him that he liked driving a cab. Suddenly he felt like talking.

“You covering a story?”

His eyes bloodshot with fatigue, Asakawa was looking out the window and letting his mind drift when the driver asked this.

“Eh?” he replied, suddenly alert, wondering how the cabby knew his profession.

“You’re a reporter, right? For a newspaper.”