скачать книгу бесплатно

It was a terrible shock. When Stalin heard her cry, he came running to comfort her.

Svetlana reciprocated this role of placater. When her mother and father were arguing, she would run to her father and wrap her small hands around his boot. Only then would he calm down. Nadya’s close friend Irina Gogua, witness to such domestic arguments, remarked, “The only creature who softened [Stalin] was Svetlana.”

If her mother was cool, Svetlana got the emotional response she craved from her father. She was Stalin’s favorite child. He called her his “little sparrow” or “little fly.” It was to his knees that she flew, and from him she got the kisses and caresses her mother withheld. She took his constant absences for granted; they made his appearances all the more dramatic and the child all the more needy.

It was Nadya who embraced the Svanidze side of the family. She was particularly protective of Yakov, whom Stalin apparently treated with contempt. The adolescent boy spoke only Georgian when he joined the household. Svetlana thought this was one of the reasons her father seemed to dislike him. Stalin was reportedly self-conscious of his own Georgian-accented Russian. Svetlana would say that her father “knew Russian well in its simpler, conversational form; . . . in Russian he could not be an eloquent orator or writer, lacking synonyms, nuances, depths.”

Instead he often used silence to assert his authority, a much more effective tool to control others, who could never figure out quite what Stalin was thinking.

As a child, Svetlana didn’t even know that her father’s roots were Georgian. Once her brother Vasili, who constantly teased her, told her that the family were Georgians. When Svetlana asked him what being Georgian meant, he said that “they went around in long Circassian cloaks and cut everybody up with daggers.”

Svetlana claimed that Stalin, seeking to distance himself from his roots, banned visiting Georgian colleagues from bringing the usual gifts of Georgian wines and fruit, raging that such generosity came at public expense, and Nadya concurred.

Looking back, Svetlana said the room she most loved in their Moscow apartment was her mother’s room. In her mother’s absence, she would retreat there whenever she could to sit on its thick, raspberry-colored Oriental rug or curl up on the old-fashioned Georgian takhta (divan) with its embroidered cushions. She loved to touch the books on Nadya’s desk and drawing table. Given the dangerous household in which she grew up, Svetlana needed this idealized image of the beloved mother for psychic survival, but the outsider sees only an absent mother and a desperate, emotionally needy child. Of course, the truth was that Nadya herself was barely surviving.

Life at Zubalovo

Buried in the minds of those of us who are lucky is a childhood landscape, a place of magic and imagination, a safe place. It is foundational, and we will return to it in memory and dreams throughout our lives. Despite what her life would become, Svetlana had such a place.

As a member of Lenin’s inner circle, Stalin was awarded a dacha called Zubalovo. It was not far from the village of Usovo, about twenty miles outside Moscow. The family lived there weekends and summers from 1919 to 1932, and the extended family continued to visit until 1949, long after Nadya’s death.

The dacha took its name from the former owner, Zubalov, an Armenian oil magnate from Baku. The whole area around Usovo had once served as a vacation retreat for the wealthy in prerevolutionary Moscow. After the owners fled during the Revolution, the dachas were divided among the Party elite. Stalin and Anastas Mikoyan got Zubalovo. There was more than a small amount of revenge in this. Both men had directed strikes protesting the long working hours and miserable conditions at Zubalov’s oil refineries in Baku, Azerbaijan; and Batumi, Georgia.

On the expansive grounds of Zubalovo, there were three separate houses called the big house, the small house, and the service block, all surrounded by a redbrick wall. The larger one was taken over by Mikoyan and other Old Bolshevik families. Nadya’s siblings, the Alliluyevs, and some of the Svanidzes used the service block, while Stalin and Nadya had the smaller dacha. It was always filled with visitors.

Stalin immediately had the dacha remodeled, removing the gables and old furnishings. He had a balcony built on the second floor—“father’s balcony”—and a terrace covering the back of the house. Stalin and Nadya occupied the upstairs, while the children and visiting relatives and friends lived downstairs. Purple lilac bushes framed the front of the house, and a grove of white birch stood at a slight distance. There was a duck pond, an apiary, a fenced-in run for chickens and pheasants, an orchard, and a clearing where buckwheat was planted to attract the bees. This Bolshevik estate served much the same role as it had when owned by the industrial elite, “a small estate with a country routine of its own” as Svetlana described it.

As a child, Svetlana knew the landscape like her own skin. She knew where the best mushroom patches could be found; she fished every stream and pond with her grandfather and brother and discovered where the trout rested in the slipstreams. She knew where to pick the berries among the brambles, which left her arms and legs covered in scratches. She brought home buckets of berries for the cook and, happy and exhausted, waited for praise. Svetlana had her own garden plot to tend and her own rabbits to raise. The smell of the larch trees, the white skin of the peeling birches, the flamboyant green of the new leaves, the smell of Russian soil—all this imprinted itself on her mind.

During the summer many children of the ruling elite came to stay. She’d lead them to the poultry yard to collect the eggs of the guinea fowl and pheasants or take them out on expeditions to pick mushrooms. On the estate they had a tree house to climb into and swings and a seesaw to ride. The children went camping in the woods, sleeping in a lean-to overnight and fishing in the local river. They would cook their catches over the fire, and bake pheasant eggs in the hot cinders.

Stalin, who had learned to love Russian baths in Siberia, eventually had a banya built at Zubalovo. It was a roofed hut with birch branches in the eaves sending their fragrance over the bathers. When her father was absent, Svetlana used to read her children’s books there, spread out on a rug on the floor.

Relatives floated into and out of Zubalovo: her grandparents Olga and Sergei Alliluyev; her Aunt Anna and Uncle Stanislav; and Uncle Pavel and Aunt Zhenya. Uncle Pavel told stories of the time after the Civil War when Lenin sent him on an expedition to the far north to prospect for iron ore and coal. They’d lived in tents, ridden reindeer, and made their clothes from reindeer pelts.

The Svanidzes also came to the dacha, particularly Uncle Alyosha and his dramatic wife, Maria. Stalin was often there but preoccupied. He could be found sitting at his table working on the terrace.

Svetlana’s grandparents, Olga and Sergei, were the dominant presences at the dacha. It was Sergei who brought Stalin into the Alliluyev household. The Russian-born son of a freed serf, he had trained himself as a mechanic and was working at the Tiflis rail yards when he joined the Mesame Dasi (Third Group), the Georgian socialist party formed in the early 1890s. He first met Stalin in 1900, when his future son-in-law was already famous locally for his brilliant organization and political exhortations at the clandestine May Day workers’ demonstrations. In those days, Sergei was mostly in charge of printing Marxist propaganda posters and leaflets, for which he was arrested and jailed seven times. Whether he participated in revolutionary violence is unclear, though he seemed to have had no objections when his nine-year-old daughter, Anna, was used by the revolutionaries as a mule to carry explosive cartridges sewn into her undervest on the train from Tiflis to Baku.

Sergei offered the family’s apartment as a refuge for Stalin when he was hiding out from the tsar’s secret police.

Olga was a more complex figure. In 1893, she’d run off with Sergei, who was the family’s lodger, to escape her tyrannical father. She was sixteen; he was twenty-seven. She seemed a willing ally in Sergei’s revolutionary politics. Her life and the lives of her four children had been a narrative of constant moving from city to city, police searches, fear, keeping secrets, visiting Sergei in prison, and watching friends disappear. She distributed Marxist tracts, as did her young daughters, a dangerous practice that could bring them a jail term as it did their father. It was she who suggested their Saint Petersburg apartment on Rozhdestvenskaya Street as a hiding place for Lenin in the summer of 1917, when he stayed for several days before fleeing to Finland when the Revolution seemed to be dissolving, only to return to organize the Bolshevik triumph that October. And she also welcomed Stalin’s visits. Stalin was effusive in his gratitude to Olga, writing to her from his Siberian exile:

NOVEMBER 25, 1915

Olga Eugenievna:

I am more than grateful to you, dear Olga Eugenievna, for your kind and good sentiments toward me. I shall never forget the concern which you have shown me. I await the time when my period of banishment is over and I can come to Petersburg, to thank you and Sergei personally, for everything. I still have two years to complete it all. . . . My greetings to the boys and girls. . . .

Respectfully yours,

Joseph

This was the son-in-law who would one day betray her every trust.

As soon as her youngest daughter, Nadya, turned fourteen, Olga asserted her independence by undertaking training as a midwife. When Russia entered World War I, she joined the Red Cross, tending the wounded who arrived from the German front. She lived mostly at the hospital and, according to her son Pavel, began to take lovers.

By the time they were in residence at Zubalovo, Sergei and Olga were completely alienated. He would arrive from one end of the dacha, she from the other, and they would stare each other down across the length of the dining room table. Sergei had been sidelined as an Old Bolshevik, though he remained a fervent believer, while Olga seemed skeptical, and was the earliest to suspect the true nature of her son-in-law.

Through those long summers at the dacha, this seemed an explosive, hot-tempered, typically Georgian family—Grandpa Sergei, angry when a child was restless at the table, was known to pour his soup into the child’s lap.

Olga had reverted to her Eastern Orthodox religion. When the Stalin children and their friends, brought up in the atheistic ideology of Communism, mocked Grandma Olga’s beliefs, she would respond, “Where is your soul? You will know when it aches.”

However, she didn’t seem to mind the ascendency and benefits her son-in-law’s position gave her.

Svetlana, who inherited Olga’s red hair and blue eyes, identified with her grandmother. She claimed that her mother had banned her grandmother from visiting their Kremlin apartment because she resented Olga’s constant criticism of her Bolshevik devotion to her career and her failure to stay at home with her children.

Svetlana probably picked this up from her aunts, as it is hardly the memory of a six-year-old child. Apparently Olga would shout at Nadya that she’d brought up four children, though Nadya, remembering her fractured childhood, might have found this ironic. Olga was explosive but not particularly self-reflective, traits her granddaughter Svetlana also seemed to inherit.

As a child, Svetlana would not have had much understanding of these complex family undercurrents. What child does? At Zubalovo, her grandparents, and particularly her grandfather, were benevolent parental substitutes. Sergei kept a machine shop in a separate hut at the dacha and invited the children into his workshop to play with his tools and make things. Sometimes he would hang candy from the trees for them to pluck and take them on long mushroom-picking hikes through the forest.

Svetlana’s maternal grandfather, Sergei Alliluyev, in the late 1920s.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Many of the Bolshevik Party elite shared those summers at Zubalovo. Svetlana called all of them uncles. “Uncle Voroshilov” and “Uncle Mikoyan” came to the Stalin dacha with their families. One of the visitors she liked best was Stalin’s old comrade Nikolai Bukharin, who filled the dacha with laughter and was loved by everyone. He taught Svetlana’s nanny to ride a bike and always brought animals to the dacha and the Kremlin gardens: hedgehogs, garter snakes in jars, hawks, even a tame fox. Long after Stalin had Bukharin executed in the final show trial of 1938, his fox still ran through the Kremlin gardens. Other friends came, like Sergo Ordzhonikidze and his wife, Zinaida. As a six-year-old, Svetlana watched the adult parties with a child’s curiosity: Semyon Budyonny played the accordion and the adults sang Russian folk songs. Even Nadya might dance the Georgian lezghinka, and Stalin, who had an excellent singing voice and fine pitch, might also sing.

Only Mikoyan, Budyonny, and Kliment Voroshilov outlasted Stalin. These “uncles” and “aunts” began to disappear in the mid-1930s; many were executed, and some, like Ordzhonikidze, committed suicide. Svetlana remembered only that, as a child, she couldn’t understand where everybody had gone. People simply “vanished.” No one explained why.

Stalin was forty-eight when Svetlana was born, and he preferred his vacations without noisy children. He and Nadya often took vacations in Sochi on the Black Sea, where the warm baths helped his rheumatism, in all likelihood a product of his numerous Siberian exiles. It seemed that often a whole retinue of Party members would drive south in a flotilla of cars. Svetlana kept her mother’s photographs of those trips. There was the image of Abel Enukidze, her mother’s beloved godfather, at picnics on the beach. Other Politburo members, like Molotov, Mikoyan, and Voroshilov, would be there. Taking vacations together was part of Party orthodoxy. Stalin had a deformed arm as a result of childhood accidents, as well as webbed toes on one foot, so he never swam. He preferred to stretch out on a deck chair on the beach reviewing documents. Svetlana was five years old before she was allowed to accompany her parents to their dacha in Sochi.

Looking back in her memoir, written when she was thirty-seven, Svetlana could speak only of these leaders’ “deaths,” not of their murders. “I want to put down only what I know and what I remember and saw myself,” is how she keeps the psychological trauma at a distance.

But here the split begins: Zubalovo was once a place of light and magic where old friends, revolutionary comrades, gathered to share summers and laughter with their children. And then everything turned murderously black.

In retrospect Svetlana would not deny the paradox of that childhood happiness. Its privileged isolation protected her from the terrible suffering of the time: the brutal internal Party struggles as Stalin asserted his ascendency over his rivals with purges of Old Bolsheviks and the Party elite; the deaths of millions of peasants from man-made famines caused by forced collectivization in the countryside in the name of rapid industrialization. The classless Bolsheviks had replicated the tsarist regime: now the people were the serfs and the leaders walled themselves within safe boundaries. There were not then the bourgeois excesses that the regime would become famous for after the war.

Nor could Svetlana deny the magic of that first world, when she lived with the timeless unconsciousness of a child in a place peopled with beings she loved. Should she merely have rejected this whole world? But she was at the core of a paradox. How could a world that seemed wonderful be also terrible? Her father petted and loved her and showered her with paternal tobacco kisses as, at her nanny’s urging, she trotted up to him with presents of violets and strawberries. How could he already be at the same time one of the world’s bloodiest dictators, biding his time?

Svetlana called her childhood normal, full of loving relatives, friends, holidays, pleasure. She even claimed that it was modest, and for the child of a head of state, perhaps it was, though the millions of Russians who were starving and displaced would have been outraged.

In her memoir she wrote: “If only out of respect for their memory, from love and profound gratitude for what they were to me in that place of sunshine I call my childhood, I ought to tell you about them.”

It was a willful declaration, for the memories were full of paradoxes and frustrations. “I keep trying to bring back what is gone, the sunny, bygone years of my childhood,” she would write over thirty years later, as if acknowledging the impossibility of this.

From the child’s point of view, the world may have been undiluted sun, though with a child’s intuition, she must already have sensed the cracks in her paradise. From an adult perspective, it was a labyrinthine tangle of pain and anxiety.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_3dc26757-1995-515a-a3e8-085b8d9e246c)

A Motherless Child (#ulink_3dc26757-1995-515a-a3e8-085b8d9e246c)

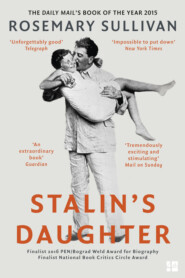

Nadya with a young Svetlana, c. 1926.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

During the afternoon of November 7, 1932, Svetlana stood with her mother at the front of the crowd watching the soldiers march past the Hall of Columns to honor the fifteenth anniversary of the Great Revolution. This was the first time she had been allowed to attend the annual celebrations. It was an extraordinary festival, with stilt walkers, fire-eaters, and circus performers moving into and out of the throng of thousands of people. She looked up at her father on the platform where his giant image hung behind the Party magnates lined up dutifully on either side of the vozhd. She was only six and a half, but she understood that her father was the most important man in the world.

Earlier that day, her mother had called her into her room. “I saw my mother so rarely that I remember our last meeting very well.” Svetlana sat on her favorite takhta and listened as her mother delivered a long lesson on manners and deportment. “Never drink wine!” she said.

Nadya and Stalin always quarreled when he dipped his finger into his wine and put it into his children’s mouths. She protested that he would turn her children into alcoholics. Her final words to Svetlana were in character. Nadya dismissed as self-indulgence the emotional effusiveness that she associated with her mother, Olga; and her sister, Anna. Crying, confessions, complaining, and even frankness were not in her repertoire. The most important thing was to do one’s duty and to hide one’s secrets in the small square over one’s heart.

As her nanny put her to bed, Svetlana recounted how Uncle Voroshilov led the whole parade riding on a white horse.

On the morning of November 9, Alexandra Andreevna got the children up early and sent them out to play in the dark, rainy dawn. When they were bundled into a car hours later, the staff all seemed to be crying. They were driven to the new dacha at Sokolovka. Stalin had begun to indulge his penchant for building dachas, and that fall the family was using the Sokolovka dacha instead of Zubalovo. The house was gloomy, with a dark interior that seldom got any light. The children knew something was terribly wrong and kept asking where their mother was. Eventually Voroshilov arrived to take them back to Moscow. He was in tears. Their father seemed to have disappeared.

So many apocryphal stories have gathered around what had happened the previous night that it is impossible to sort fact from fiction, gossip from truth, but a rough outline of the night can be reconstructed.

In the late afternoon of November 8, Nadya was in the apartment in the Poteshny Palace preparing for the inevitably boisterous party to celebrate the Revolution. Her brother Pavel, currently stationed in Berlin as the military representative with the Soviet trade mission, was visiting and had brought her gifts, one of which was a lovely black dress. The Kremlin wives always complained that when they met Nadya at the fashionable Commissariat of Internal Affairs dressmaker on Kuznetsky Bridge, reserved for the Party elite, she selected the most drab and uninteresting clothes. They were amused that she was still following the outdated Bolshevik ethic of modesty.

That night, in her elegant black dress, she was beautiful; she had even placed a red rose in her black hair.

Accompanied by her sister, Anna, Nadya crossed the snowy lane to the Horse Guards building and entered the apartment of Comrade Voroshilov, the defense commissar, who was hosting the anniversary celebration for the Party magnates and their wives. Stalin sauntered down the lane from his office at the Yellow Palace in the company of Comrade Molotov and his chief of economics, Comrade Valerian Kuibyshev. They had only one or two guards with them, though the Politburo had banned the vozhd from “walking around town on foot.”

The Politburio had concluded that Stalin was no longer safe, so hated were the policies of terror he had already adopted against so-called industrial saboteurs, bourgeois experts, and political terrorists conspiring with foreign powers. Assassination seemed a real possibility.

For everyone this was an occasion to unwind. The food arrived from the Kremlin kitchen—an ample spread of hors d’oeuvres, fish, and meat, with vodka and Georgian wine—served by the housekeeper. The men, many still sporting the tunics and boots that were a throwback to their revolutionary past, and the women in their designer dresses, sat at the banquet table. Stalin sat in his usual spot in the middle of the table, across from Nadya. This was a hard-drinking, exuberant lot, ready to down toast after toast to the old revolutionary triumphs and the new industrial achievements.

In the anecdotal reports in the multiple memoirs left behind by those present at the party that night, stories coalesce around the following details. Stalin was drunk and was flirting boorishly with Galina, a film actress and the wife of the Red Army commander Alexander Yegorov, by lobbing bread balls at her. Nadya was either disgusted or simply tired of all this. There had been gossip about Stalin’s current dalliance, with a Kremlin hairdresser. Stalin liked to confine his philandering to those from whom discretion could be ensured, and a hairdresser working at the Kremlin would have belonged to the secret police. Nadya had seen it all before and knew these affairs never lasted, though neither she nor anyone else seemed to know how far they went. Years later Stalin’s bodyguard Vlasik made the suggestive comment to Svetlana that her father “was a man after all.”

That night, Nadya was seen dancing coquettishly with her Georgian godfather, Abel Enukidze, then administrator of the Kremlin complex, a usual stratagem for an angry woman to demonstrate her studied indifference to her husband’s flirtations.

Many accounts claim that it was a political toast that inflamed Nadya. Stalin toasted “the destruction of enemies of the state” and noticed that Nadya did not raise her glass. He shouted across the table, “Hey you, why aren’t you drinking? Have a drink!”

She replied venomously, “My name is not hey,” before storming out of the room. The revelers could hear her shouting over her shoulder, “Shut up! Shut up!” as she exited. The room fell silent in shock. Not even a wife would dare turn her back on Stalin. Stalin only muttered contemptuously, “What a fool,” and kept on drinking.

Nadya’s close friend Polina Molotov rushed out after her. According to Polina, she and Nadya circled the Kremlin a number of times as Polina reminded her of how much pressure Stalin was under. He was drunk, which was rare: he was just unwinding. Polina said Nadya was “perfectly calm” when they said good night in the early hours of the morning.

When Nadya returned to the Kremlin apartment, she entered her room and closed the door. After fourteen years of marriage, she and Stalin slept separately. Her room was down a hall off to the right from the dining room. Stalin’s room was to the left of the dining room. The children’s rooms were down another hall, and much farther down that hallway came the servants’ rooms.

Sometime in the early hours of the morning, Nadya took the small Mauser pistol that her brother Pavel had given her as a gift and shot herself in the heart.

Nobody seems to have heard the shot—certainly not the children and none of the servants. In those days, the guard stood outside at the gate. Stalin, if he was home, seems to have slept through it all.

The housekeeper, Carolina Til, prepared Nadya’s breakfast, as she did every morning. She claimed that when she entered the room, she found Nadya lying on the floor beside her bed in a pool of blood, the little Mauser pistol still in her hand. Til ran to the nursery to wake Svetlana’s nanny, Alexandra Andreevna, and together they went back to Nadya’s room. The two women laid Nadya’s body on the bed. Rather than call Stalin, whose anticipated reaction terrified them, they phoned Nadya’s godfather, Abel Enukidze, and then Polina Molotov. The group waited. Finally Stalin woke and entered the dining room. They turned to him: “Joseph, Nadya is no longer with us.”

Rumors would later surface that, after the party, Stalin had gone to the Zubalovo dacha with another woman and had arrived home in the wee hours of the morning. He and Nadya quarreled, and he’d shot her. Stalin was a kind of magnet for vengeful myths, but this one is unlikely. More convincing is the relatives’ certainty that Nadya committed suicide, and they were angry: how could she abandon her children like that?

They also claimed Nadya left a bitter and accusatory suicide note for Stalin, though supposedly he destroyed it immediately upon reading it. Pavel’s wife, Zhenya, reported that for the first few days, Stalin was in a state of shock. “He said he didn’t want to go on living either. . . . [Stalin] was in such a state that they were afraid to leave him alone. He had sporadic fits of rage.”

Nadya and Stalin together at a picnic, from a photo taken in the early 1920s.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

The family needed to believe that he was devastated, and it is possible that he was. He had, in his way, loved Nadya, as his love letters to her attest. Even dictators can be sentimental. But his reaction was cruelly egocentric and focused on himself. Stalin’s sister-in-law, Maria Svanidze, recorded in her private diary the moment when she told Stalin that she blamed Nadya: “How could Nadya have left two children?” He responded, “The children have forgotten her after a few days, but I am left incapacitated for the rest of my life.”

It is hard to imagine a father saying this of his grieving children, but Stalin’s self-pity seems convincing. Svetlana always believed, more realistically, that her mother’s suicide exacerbated Stalin’s paranoia: No one could ever be trusted; even those closest betrayed.

Why did Nadya, just thirty-one, kill herself? We will never know the truth, but speculations abound. The easiest explanation is that she was mentally ill. Initially, even Svetlana believed this. The historian Simon Sebag Montefiore writes: “[Nadya’s] medical report, preserved by Stalin in his archive, and the testimonies of those who knew her, confirm that Nadya suffered from a serious mental illness, perhaps hereditary manic depression or borderline personality disorder though her daughter called it ‘schizophrenia,’ and a disease of the skull that gave her migraines.” Nadya suffered multiple other ailments. She had had several abortions, a not uncommon form of contraception in those days, which resulted in a number of gynecological problems.

She retreated to spas and German health resorts, an indulgence, indeed almost a fetish, of most of the Party elite.

But eventually Svetlana came to see her mother’s despair as motivated by her opposition to Stalin’s repressive policies. The question is whether there is any credibility to this idea.

Nikita Khrushchev, her fellow student at the Industrial Academy, claimed Nadya tried to assert her independence from Stalin.

When she registered at the Academy in 1928, she retained her own name, Alliluyeva, though in truth this was not unusual among Bolshevik wives. She refused to travel to the Academy in a government car and rode the tram; this was why she had a pistol. Her brother Pavel had brought back two Mauser No. 1 pistols from a trip to England, giving one to Nadya and one to Molotov’s wife, Polina. Alexander Alliluyev, Pavel’s son, would later remark, “They took the tram to their school, and there was some real danger at that time in Moscow. Because of that, my father brought those two damned pistols from England. And in regards to this, Stalin said to my father, ‘You couldn’t find another gift?’ The gun had tiny bullets, but they were enough for Nadya to shoot herself in the heart.”

From her correspondence as a teenager, it is easy to see Nadya as a dogmatic, idealistic young Communist. During the Civil War that raged after the Bolsheviks’ triumph, she seemed able to rationalize the violence as necessary to the survival of the Great Revolution. When, in June 1918, Lenin sent Stalin south to Tsaritsyn (renamed Stalingrad in 1925) with 450 Red Guards to secure food supplies for Moscow and Petrograd, the seventeen-year-old Nadya and her brother Fyodor accompanied him as his assistants. A railway carriage was pulled to a siding, and Stalin used it as his headquarters. They hadn’t yet registered their marriage, but under Bolshevik convention, Nadya was already considered Stalin’s wife.

Immediately Stalin began to purge the city of suspected counterrevolutionaries. When he wrote repeatedly to Lenin demanding sweeping military powers, Nadya typed his letters. When Lenin ordered him to be ever more “ruthless” and “merciless,” Stalin replied, “Be assured that our hand will not tremble.”

Stalin conducted a campaign of “exemplary terror.” He burned villages to show the consequences of failure to comply with the Red Army’s orders and to demonstrate what counterrevolutionary sabotage would lead to. His enthusiasm for indiscriminate violence did not seem to faze Nadya, typing away in her railway carriage.

Nadya loved Stalin and seemed comfortable rationalizing, indeed even glamorizing, the Bolshevik cult of violence. The passionate love letters they sent each other when they were apart had an electric, if conventional, intensity. As late as June 1930, when Nadya was in Carlsbad talking a cure for debilitating headaches (another report suggests that she was actually suffering acute abdominal pains, possibly from an abortion), Stalin wrote: “Tatka [his pet Georgian name for her]. Do write to me something. . . . It is very lonely here, Tatochka. Am sitting at home, alone, like a little owl. I have not been to the country—too much work. I have finished my own task. I plan to go the day after tomorrow to the country, to the children. Well, good-bye. Do not stay there for too long, come back soon. I—kiss—you. Yours, Josef.”

One of her letters to him ended: “I beg you to take good care of yourself. I kiss you warmly, as you had kissed me at my leaving. Yours, Nadya.”

But domestic life with Stalin had a different tenor and was extremely volatile. Nadya made a first attempt to leave him in 1926, when Svetlana was only six months old. After a quarrel, she packed up Svetlana, Vasili, and Svetlana’s nanny and took the train to Leningrad (as Saint Petersburg was renamed in 1924 after Lenin’s death), where she made it clear to her parents that she was leaving Stalin and intended to make her own life. He telephoned and begged her to come back. When he offered to come to get her, she replied, “I’ll come back myself. It’ll cost the state too much for you to come here.”

Perhaps Stalin’s worst characteristic as a husband was the tantalizing quality of his affection. With her pride and reticence, Nadya rarely revealed family secrets, but her sister Anna remarked that she was a “long-suffering martyr.” Stalin, usually distant and inscrutable, could flare up with an uncontrollable temper and could be callously indifferent to his wife’s feelings. Nadya complained that she was always running Stalin’s errands—he needed a document in the commissar’s office; he needed a book from the library. “We wait for him, but never know when he will come home.”

Nadya’s second year at the Industrial Academy, 1929, was the Year of the Great Turn and the forced collectivization of the peasantry into kolkhozy, or collective farms. The process was brutal. In order to root out private enterprise, village markets were shut down and livestock was confiscated. Kulaks, or prosperous peasants (owning one cow could constitute prosperity), were deported. Under this policy, known as dekulakization, peasants, “treated like livestock . . . often died in transit because of cold, starvation, beatings in the convoys, and other miseries.”

By the year of Nadya’s death, 1932, the infamous Gulag (forced-labor camps) held “more than a quarter of a million people,” and 1.3 million, “mainly deported kulaks,” were living as “special settlers.”

In 1932 and 1933, famine raged in the Ukraine. Stalin and his ministers were shipping grain supplies abroad to pay for smelters and tractors in order to sustain the rapid pace of industrialization. Though the Ukraine Politburo begged for emergency relief, no assistance came. Millions died. In 1932, a number of Nadya’s fellow students at the Industrial Academy were arrested for speaking out about the famine. Nadya, too, was rumored to oppose “collectivisation and its immorality.” Critical of Stalin, she secretly sympathized with Nikolai Bukharin and the right-wing opposition.

Stalin commanded Nadya to stay away from the Academy for two months.

In the early days, Nadya attempted to exert some influence. When Stalin was vacationing alone in Sochi in September 1929, Nadya wrote him a careful letter, reporting that the Party was exploding over a dispute at Pravda; an article had been published without first being cleared by the Party hierarchy. Though many had seen the article, everyone was laying the blame on her friend Leonid Kovalev, and demanding his dismissal. In a long letter with the simple salutation “Dear Josef,” she wrote:

Don’t be angry with me, but seriously I felt pain for Kovalev, for I know the colossal work that he has done in the paper. . . . To dismiss Kovalev . . . is simply monstrous. . . . Kovalev looks like a dead man. . . . I know that you detest my interference, but still I believe that you should look into this absolutely unjust outcome. . . . I cannot be indifferent about the fate of such a good worker and comrade of mine. . . . Good-bye, now, I kiss you tenderly. Please, answer me.

Stalin wrote back four days later: “Tatka! Got your letter regarding Kovalev. . . . I believe you are right. . . . Obviously, in Kovalev they have found a scapegoat. I will do all I can, if it is not too late. . . . I kiss my Tatka many, many, many times. Yours, Josef.”

Stalin did act on Nadya’s request and wrote to Sergo Ordzhonikidze, in charge of adjudicating cases of disobedience to Party policies, to say that scapegoating Kovalev was “a very cheap but wrong and unbolshevik method of correcting one’s faults. . . . Kovalev . . . IN NO CIRCUMSTANCES WOULD EVER let one line about Leningrad be printed, had it not been silently or directly approved, by somebody at the bureau.”

Kovalev was eventually dismissed from Pravda—not as an “enemy of the people” but rather as “a straying son of the Party.”