скачать книгу бесплатно

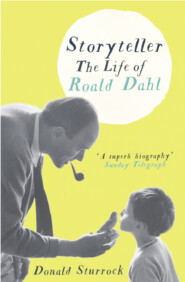

Storyteller: The Life of Roald Dahl

Donald Sturrock

The authorised biography of one of the greatest storytellers of all time, written with complete and exclusive access to the archives stored in the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre.Roald Dahl pushed children's literature into new and uncharted territory. More than fifteen years after his death, his popularity around the globe continues to grow, and worldwide sales of his books have now topped 100 million.The man behind the stories, however, remains an enigma. Dahl was a single-minded adventurer, an eternal child, but his public persona was characterised by his blunt opinions on taboo subjects. Described as an anti-Semite, a racist and a misogynist, he felt ignored and undervalued by the literary establishments of London and New York.To his readers, though, Dahl was always a hero, and since his death his reputation has been transformed. His wild imagination is now celebrated, along with his quirky humour and his linguistic elegance. Figures like Willy Wonka, the BFG and the Grand High Witch are nothing less than immortal literary creations, and in a recent poll he beat J. K. Rowling to win the title of Britain's favourite author.In this masterly biography, Donald Sturrock draws on a huge range of source material that has become available since Dahl's death. The result is revealing, compelling and a pure joy to read.

DONALD STURROCK

Storyteller

The Life of Roald Dahl

Copyright (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

Harper Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2010

This ebook edition first published in 2010

Copyright © Donald Sturrock 2010

Cover photograph © Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Some images were unavailable for the electronic edition.

Donald Sturrock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007254774

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007397068

Version: 2016-10-12

For my parents, Gordon and Margaret

I don’t lie. I merely make the truth a little more interesting …

I don’t break my word—I merely bend it slightly….

ROALD DAHL, from his Ideas Books, No. 1 (c. 1945-48)

Contents

Cover (#u9b0d2f6f-018e-54f5-b57f-d10d118d2009)

Title Page (#u27d41592-508d-5944-bf7c-b9972a98b256)

Copyright

Dedication (#u5cf0f8f8-207a-5657-9f2c-655e0e6f4dff)

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

Lunch with Igor Stravinsky

ROALD DAHL THOUGHT BIOGRAPHIES were boring. He told me so while munching on a lobster claw. I was twenty-four years old and had been invited for the weekend to the author’s home in rural Buckinghamshire. Dinner was in full swing. A mixture of family and friends were devouring a platter brimming with seafood, while a strange object, made up of intertwined metal links, made its slow way around the table. The links appeared inseparable, but Dahl had told us all they could be separated quite easily by someone with sufficient manual dexterity and spatial awareness. So far none of the guests had been able to solve it. As I waited for the puzzle to come round to me, I tried to respond to Roald’s disdain for biography. I mentioned Lytton Strachey, Victoria Glendin-ning, Michael Holroyd. But he wasn’t having any of it. Sitting in a high armchair, at the head of his long pine dining table, he leaned back, took a swig from his large glass of Burgundy, and returned to his theme with renewed relish. Biographers were tedious fact-collectors, he argued, unimaginative people, whose books were usually as enervating as the lives of their subjects. With a glint in his eye, he told me that many of the most exceptional writers he had encountered in his life had been unexceptional as human beings. Norman Mailer, Evelyn Waugh, Thomas Mann and Dr Seuss were, I recall, each dismissed with a wave of his large hand, as tiresome, vain, dreary or insufferable. He knew I loved music and perhaps that was why he also mentioned Stravinsky. “An authentic genius as a composer,” he declared, throwing back his head with a chuckle, “but otherwise quite ordinary.” He had once had lunch with him, he added, so therefore he spoke from experience. I tried to think of subjects whose lives were as vivid as their art: Mozart, Caravaggio, Van Gogh perhaps? His intense blue eyes looked straight at me. That wasn’t the point, he said. Why on earth would anyone choose to read an assemblage of detail, a catalogue of facts, when there was so much good fiction around as an alternative? Invention, he declared, was always more interesting than reality.

As I sat there, observing the humorous but combative glint in his eye, I sensed that, like a boxer, he was sparring with me. He had thrown a punch and been pleased that I jabbed back. Now he had thrown me another. This one was more difficult to parry. It would be hard to take it further without the exchange becoming detailed and perhaps wearisome. I hesitated. I wondered at his own life. He had just written two volumes of memoirs, one of which he had given to me to read in draft. So I knew the rough outline of his first twenty-five years: Norwegian parents, a childhood in Wales, miserable schooldays, youthful adventures in Newfoundland and Tanganyika, flying as a fighter pilot, a serious plane crash, then a career as a wartime diplomat in Washington. I had already told him privately that I found the books compelling. Did he want me to repeat the compliment over dinner as well? It was hard to tell. At that moment the metal links were presented to me and the conversation moved on. Soon, too, his huge pointy fingers had plucked the puzzle from my inept hands and he had begun confidently to demonstrate its solution. Later on, at the end of a meal which had concluded with the offer of KitKats and Mars Bars dispensed from a small red plastic box, he took his two dogs out into the garden. A few minutes later he returned, wished everyone good night, and retired theatrically from the public space of the drawing room into the privacy of his bedroom.

Half an hour later, I was walking up the frosty path from the main building to the guest house in the garden. The atmosphere was absolutely still. A fox shrieked in the distance. I stopped for a moment and looked up at the clear winter sky. I was struck by how many stars I could see. Great Missenden was less than an hour’s drive from London, but the lights of the city seemed far, far away. Some cows stirred in a nearby field. I looked about me. Gentle hills curved around the garden on all sides. At the top of the lane a vast beechwood glowered. The dark outline of the 500-year-old yew tree that had inspired Fantastic Mr Fox loomed over me. In the orchard, moonlight glinted on the gaily painted gypsy caravan that he had recreated in Danny the Champion of the World. An owl fluttered low into the yew. I turned and opened the door to my room.

Soon, I found myself examining the books in the bookcase by my bedside. There was certainly no biography here. Most of it was crime fiction: Ed McBain, Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, Dick Francis. As I pulled out a volume, I noticed some ghost stories too, an insect encyclopedia, the diary of a Victorian priest, and a book of poetry by D. H. Lawrence. All of the books looked as if they had been read. I reflected again on our exchange over dinner, and wondered whether Roald had actually met Stravinsky. Perhaps he had simply made that remark to disconcert me? Before I switched off the light, I remember thinking that next day I would flush him out. I would ask him how he had come to have lunch with the great composer. Needless to say, I got distracted and forgot to do so.

It was then February 1986. I had known Dahl six months. The previous autumn, as a fledgling documentary director in the BBC’s Music and Arts Department, I had proposed making a film about him for Bookmark, the corporation’s flagship literary programme. Nigel Williams, the producer, himself an established playwright and novelist, had decided that the Christmas edition of the show would be devoted to children’s literature. Twenty-five years ago this was still a field that many people in the UK arts affected to despise, and for once none of the programme’s older, more experienced directors seemed keen to put forward any ideas. I was the most junior on the team. I wanted desperately to make a film. Any film. So I took my chance. It was an obvious suggestion — a portrait of the most famous and successful living children’s writer. The motivation however behind my plan was largely opportunistic. At that point, I had read none of Dahl’s children’s fiction other than Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. On the other hand, as a thirteen-year-old, I had read most of his adult short stories, feasting on them with concentrated relish from behind a school desk during maths lessons. My adolescent mind had revelled in their grotesqueries, their complex twists and turns, and their spare, elegant, strangely sexy prose.

I remember Nigel Williams’s smile. How he looked at me when I mentioned Roald Dahl. It was knowing, almost wicked. “Okay,” he said. “If you can persuade him to do it.” I paused. Was he thinking about money? The programme had a tiny budget and always paid its contributors the most modest of disturbance fees. It wasn’t cash, however, that was on Nigel’s mind. “You know his reputation?” he asked rhetorically. “Unbelievably grumpy and difficult. He’ll never agree to take part.” I nodded, although this was actually news to me, for my impression of Dahl the man at that point was in fact one of singular lightness. Four years earlier, while I was an undergraduate, he had taken part in a debate at the Oxford Union. “Romance is bunk” was the motion. Dahl had contributed to it memorably, arguing that romance was no more than a euphemism for the human sex drive. He was a great entertainer — witty, subversive, and often risque. At one point he challenged a young woman in his audience to try and “get romantic” with a eunuch. At another he joked that a castrated male was similar to an aeroplane with no engine, because neither could get up. As I walked out of Nigel’s office, all this was still fresh in my memory. Maybe Dahl will be cantankerous, I thought, but I am sure he will be funny, too. I discovered from press cuttings that he lived in a village called Great Missenden. I searched a telephone directory for Dahl, R. and there was his phone number. Ten minutes later I was calling him to discuss the project. Our conversation was brief and to the point. “Come to lunch,” he said. “There are good train services from Marylebone.”

A week later, I was standing outside the bright yellow front door of Gipsy House, his modest eighteenth-century whitewashed home. I rang the bell. An explosion of dogs barking heralded the arrival of a gigantic figure in a long red cardigan. He looked down at me. He was six foot five inches tall, craggy and broad of beam. His body seemed larger than the doorway and far, far too big for the proportions of the cottage. He ushered me through into a cosy sitting room where a log fire burned generously in the fireplace. He seemed a trifle surprised. I asked if I had got the date wrong. “No,” he said. “I was expecting you.” He asked me to wait a moment, then left the room. His strides were huge and ponderous, but strangely graceful — a bit like a giraffe. On one wall a triptych of distorted Francis Bacon heads glared out at me alarmingly, reminding me that for years, Dahl’s adult publishers had dubbed him “the Master of the Macabre”. On an adjacent wall, another Bacon head — this one a distorted swirl of green and white — returned my gaze. Around them a dazzlingly eclectic group of paintings and artefacts decorated the room: colourful oils, a collection of outsize antique Norwegian pipes, a primitive mask, a sober Dutch landscape and some stylized geometric paintings. I learned over lunch that these were the works of the Russian Suprematists: Popova, Malevich and Goncharova.

His wife Liccy (pronounced “Lici” as in the middle two syllables of her name, Felicity) returned five minutes later and suggested I go through into the dining room, where he was waiting for me. Over a lunch of smoked oysters, served from a tin — I don’t recall any wine — we discussed the documentary. In the week leading up to our meeting I felt I had become an expert on his work and had read everything of his that I could get my hands on. I asked him some questions about his early life and about childhood. He told me how easy he found it to see the world from a child’s perspective and how he thought that this was perhaps the secret to writing successfully for children. His memoir of childhood, Boy, had recently been published. I wanted to use this as the backbone of the film and so we talked about Repton, the school where he had spent his teenage years, fifty years earlier. He told me what a miserable time he had had there and we talked about the ethics of beating, for which the school was famous. We pencilled some provisional shooting dates in his diary. Then I asked whether I could see his writing hut. I had read about it and wanted to film there. I anticipated he might say no and tell me that it was too private a place to show to a film crew. But he did not bat an eyelid, and, after lunch, he took me to see it. We walked down a stone path bordered with leafless lime saplings, tied onto a bamboo framework that arched gently over our heads. He explained to me that in time the saplings would grow around the structure and make a magical, shady tunnel.

He opened the door to the hut and I went inside. An anteroom, stuffed with old picture frames and filing cabinets, led directly into his writing space. The walls were lined with aged polystyrene foam blocks for insulation. Everything was yellow with nicotine and reeked of tobacco. A carpet of dust, pencil sharpenings and cigarette ash covered the worn linoleum floor. A plastic curtain hung limply over a tiny window. There was almost no natural light. A great armchair filled the tiny room — Dahl frequently compared the experience of sitting there to being inside the womb or the cockpit of a Hurricane. He had chopped a huge chunk out of the back of the chair, he told me, so nothing would press onto the lower part of his spine and aggravate the injury he suffered when his plane crashed during the war. A battered anglepoise lamp, like a praying mantis, crouched over the chair, an ancient golf ball dangling from its chipped arm. A single-bar electric heater, its flex trailing down to a socket near the floor, hung from the ceiling. He told me that by poking it with an old golf club he could direct heat onto his hands when it was cold.

Everything seemed ramshackle and makeshift. Much of it seemed rather dangerous. Its charm, however, was irresistible. An enormous child was showing me his treasures: the green baize writing board he’d designed himself, the filthy sleeping bag that kept his legs warm, and — most prized of all — his cabinet of curiosities. These were gathered on a wooden table beside his armchair and included the head of one of his femurs (which had been sawn off during a hip replacement operation twenty years earlier), a glass vial filled with pink alcohol, in which some stringy glutinous bits of his spine were floating, a piece of rock that had been split in half to reveal a cluster of purple crystals nestling within, a tiny model aeroplane, some fragments of Babylonian pottery and a metal ball made, so he assured me, from the wrappers of hundreds of chocolate bars. Finally, he pointed out a gleaming steel prosthesis. It had been temporarily fitted into his pelvis during an unsuccessful hip replacement operation. He was now using it as an improvised handle for a drawer on one of his broken-down filing cabinets.

The shooting went without incident. Though it was the first time he had ever been filmed in his writing hut, and indeed the first time that the BBC had made a documentary about him, there were no rows, no difficulties, and no grumpiness. Roald charmed everyone and I occasionally wondered how he had come to acquire his reputation for being irascible. His short fuse had not been apparent to me at all. Years later, however, I discovered that I just missed seeing it on my very first visit. Not long after he died, Liccy explained why I had been abandoned in his drawing room. For, standing in his doorstep, I had not made a good impression. Roald had gone straight to her study. “Oh Christ, Lic, they’ve sent a fucking child,” he had groaned. Liccy encouraged him to give me a chance and I think my youth and earnestness eventually became an asset. I even felt at the end of the two-day shoot as if Roald had become a friend. In the editing room, putting the documentary together, I was reminded of the suspicion that still surrounded Dahl in literary circles. Nigel Williams, concerned that Dahl appeared too sympathetic, insisted that I shoot an interview with a literary critic who was known to be hostile to his children’s fiction. This reaction may have been largely a result of a trenchantly anti-Israeli piece Dahl had written for The Literary Review two years earlier. The article had caused a great deal of controversy and fixed him as an anti-Semite in many people’s minds. But there was, I felt, something more than this in the atmosphere of wariness and distrust that seemed to surround people’s reactions to him. Something I could not quite put my finger on. A sense perhaps that he was an outsider: misunderstood, rejected, almost a pariah.

I must have visited Gipsy House six or seven times in the next four years. Gradually, I came to know his children: Tessa, Theo, Ophelia and Lucy. Many memories of those visits linger still in the brain. Roald’s excited voice on the telephone early one morning: “I don’t know what you’re doing next Saturday, but whatever it is, you’d better drop it. The meal we’re planning will be amazing. If you don’t come, you’ll regret it.” The surprise that evening was caviar, something he knew I had never tasted. True to the spirit of the poacher at his heart, he later explained that it had been obtained, at a bargain price, in a furtive transaction that seemed like a cross between a John Le Carre spy novel and a Carry On film. The code phrase was: “Are you Sarah with the big tits?” Another evening, I remember him opening several of the hundreds of cases of 1982 Bordeaux he had recently purchased and that were piled up everywhere in his cellar. The wines were not supposed to be ready to drink until the 1990s, but he paid no attention. “Bugger that,” he declared. “If they’re going to be good in the 1990s, they’ll be good now.” They were. I recall his entrances into the drawing room before dinner, always theatrical, always conversation-stopping, and his loud, infectious laugh. Being in his company was always invigorating. You never quite knew what was going to happen next. And whatever he did seemed to provoke a story. Once, on a summer’s morning outside on the terrace, he taught me how to shuck my first oyster, using his father’s wooden pocketknife. He told me he had carried it around the world with him since his schooldays. Years later, when I told Ophelia that story, she roared with laughter. “Dad was having you on,” she explained. “It was just an old knife he had pulled out of the kitchen.”

Roald’s physical presence was initially intimidating, but when you were on your own with him, he became the most compelling of talkers. His quiet voice purred, his blue eyes flashed, his long fingers twitched with delight as he embarked on a story, explored a puzzle, or simply recounted an observation that had intrigued him. It was no surprise that children found him mesmerizing. He loved to talk. But he could listen, too — if he thought he had something to learn. We often discussed music. He preferred gramophone records and CDs to live performances — his long legs and many spinal operations had made sitting in any sort of concert hall impossibly uncomfortable — and he enjoyed comparing different interpretations of favourite pieces, seeming curiously ill at ease with relative strengths and merits. A particular recording always had to come out top. There had to be a winner. This attitude informed almost every aspect of life. Whether it was food, wine, painting, literature or music, “the best” interested him profoundly. He liked certainty and clear, strong opinions. I don’t think I ever heard him say anything halfhearted. And despite a life that had been packed with incident, he lived very much in the present and seldom reminisced. I recall only one brief conversation about being a fighter pilot and none at all about dabbling in espionage, or mixing with wartime Hollywood celebrities, Washington politicos and New York literati.

Occasionally he name-dropped. I recall him telling me, for no particular reason, that one well-known actor had been a bad loser when Roald beat him at golf. And then, of course, there was that improbable lunch with Stravinsky. But, though he was clearly drawn both to luxury and to celebrity, he took as much pleasure in a bird’s nest discovered in a hedge as he did in a bottle of Chateau Lafleur 1982 or the bon mots of Ian Fleming and Dorothy Parker. He delighted in ignoring many of the usual English social boundaries and asking people personal questions. He did it, I suspect, not because he was interested in their answer, but because he revelled in the consternation he might provoke. In that sense he could be cruel. Yet, though his fuse was a famously short one, I actually saw him explode only once. He was on the telephone to the curator of a Francis Bacon exhibition in New York, who wanted to borrow one of his paintings and had called while he had guests for dinner. She said something that annoyed him, so he swore at her furiously and slammed the phone down. I recall feeling that the gesture was self-conscious. He was playing to an audience. His temper subsided almost as soon as the receiver was back in its cradle.

Even then, I was dimly aware that this showy bravado was a veneer, a carapace, a suit of armour created to protect the man within: a man who was infirm and clearly vulnerable. Several dinner invitations were cancelled at short notice because he was unwell. Once, Liccy told me on the phone that the “old boy” had nearly met his maker. Yet he always rallied, and the next time I saw him, he would look as robust and healthy as he had been before. Always smoking, always drinking, always controversial, he appeared a life force that would never be extinguished. So his death, in November 1990, came as a shock. At his funeral, a tearful Liccy, who knew my passion for classical music, asked if I would help her commission some new orchestral settings of some of Roald’s writings and thereby achieve something he had wanted: an alternative to Prokofiev’s Peter andthe Wolf that might help attract children into the concert hall. I had just left the BBC to go freelance and jumped at the opportunity. Over the next few years, I encountered Roald’s sisters, Alfhild, Else and Asta, as well as his first wife, Patricia Neal. They all took part in another longer film I made about Dahl in 1998, also for the BBC, which Ophelia presented, and in which she and I explored together some of the themes of this book for the first time. Many of the interviews with members of his family quoted in this book date back to this period.

Shortly before he died, Roald nominated Ophelia as his chosen biographer. In the event that she did not want to perform this task, he also made her responsible for selecting a biographer. This came as something of a shock to her elder sister Tessa, who had hoped that she would be asked to write the book. Nevertheless, it was Ophelia who took up the challenge of sifting through the vast archive of letters, manuscript drafts, notebooks, newspaper cuttings and photographs her father had left behind him in his writing hut. Living in Boston, however, where she was immensely busy with her job as president and executive director of Partners in Health, the Third World medical charity she had co-founded in 1987, made the research time-consuming, and she found it increasingly hard to find time to complete the book. Eventually, when she got pregnant in 2006, she decided to put her manuscript on the shelf and asked me whether I would like to try and take up the challenge of writing her father’s biography. It was a tremendous leap of trust on her part to approach me — a first-time biographer — to write it. She did so, she told me, because I was outside the family, yet also because I had known her father and liked him. She felt that someone who had not met him would find it almost impossible to put together all the disparate pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that made up his complex and extravagant personality. Everything in the archive — now housed in the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre at Great Missenden, which had opened the previous year — was placed at my disposal. With characteristic generosity, Ophelia even allowed me to draw on the manuscript of her own memoir. Tessa too, despite an initial wariness, has subsequently freely given me her time and energies. I could not possibly have written the book without their cooperation as well as that of their siblings Theo and Lucy. I am profoundly grateful to all of them.

There were many surprises and puzzles in store for me on the journey — not least the discovery of how many contradictions animated his personality. The wild fantasist vied with the cool observer, the vainglorious boaster with the reclusive orchid breeder, the brash public schoolboy with the vulnerable foreigner, who never quite fit into the English establishment although he liked to describe himself as “very English … very English indeed”.

A delight in simple pleasures — gardening, bird-watching, playing snooker and golf — counterbalanced a fascination for the sophisticated environment of grand hotels, wealthy resorts and elegant casinos. His taste in paintings, furniture, books and music was refined and subtle, yet he was also profoundly anti-intellectual. He could be a bully, yet prided himself on defending the underdog. For one who always relished a viewpoint that was clear-cut, these incongruities were not entirely unexpected. With Roald there were seldom shades of grey. I was also to learn that, as he rewrote his manuscripts, so too he rewrote his own history, preferring only to reveal his private life when it was quasi-fictionalized and therefore something over which he could exert a degree of control. Many things about his past made him feel uncomfortable and storytelling gave him power over that vulnerability.

So now, in 2010, a wheel has come full circle. Little did I imagine when Roald and I had that conversation over dinner in 1986 that, twenty-four years later, I would finally answer his challenge by writing this book. It is an irony that I hope he would have appreciated. For seldom can a biographer have been presented with such an entertaining and absorbing subject, the narrative of whose picaresque life jumps from crisis to triumph, and from tragedy to humour with such restless swagger and irrepressible brio. Presented with so much new material — including hundreds of manuscripts and thousands of letters — I have tried, everywhere possible, to keep Dahl’s own voice to the fore, and to allow the reader to encounter him as I did, “warts and all”. Sometimes I have wished that I could convey the chuckle in his voice or seen the twinkle in his eye that doubtless accompanied many of his more outrageous statements.

Moreover, his tendencies to exaggeration, irony, self-righteousness, and self-dramatization made him a particularly slippery quarry, and my attempts to pick through the thick protective skein of fiction that he habitually wove across his past may not always have been entirely successful. I have tried to be diligent and a good fact-checker, but if a few misjudgements and errors have crept in, I hope the reader will pardon them. I make no claim to be either encyclopedic or impartial. I am not sure either is even possible. Nevertheless, I have tried to write an account that is accurate and balanced, but not bogged down in minutiae. That is something I know Roald would have found unforgivable. So, while I remain uncertain if he ever had lunch with Igor Stravinsky, I have to confess that now I no longer care. It was perhaps a STORYTELLER’s detail, a trifle. Compared with so much else, whether it was true or false seems ultimately of little importance.

CHAPTER ONE (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

The Outsider

IN JULY 1822, The Gentleman’s Magazine of Parliament Street, Westminster, reported a terrible accident. Its correspondent described how a few weeks earlier, in the tiny Norwegian hamlet of Grue, close to the border with Sweden, the local church had burned down. It was Whit Sunday and the building was packed with worshippers. As the young pastor warmed to the themes of his Pentecostal sermon, the aged sexton, tucked away in an unseen corner under the gallery, had felt his eyelids becoming heavy. By his side, in a shallow grate, glowed the fire he used for lighting the church candles. Gently its warmth spread over him and very soon he was fast asleep. Before long, a smell of burning was drifting through the airless building. The congregation stirred, but obediently remained seated as the priest continued to explain why the Holy Spirit had appeared to Christ’s apostles as countless tongues of fire. The smell got stronger. Smoke started to drift into one of the aisles. The sexton meanwhile snoozed on oblivious. By the time he awoke, an entire wall of the ancient church was ablaze. He ran out into the congregation, shouting at the worshippers to save themselves. Suffocating in the thick smoke, they pressed against the church’s sturdy wooden doors in a desperate attempt to escape the flames. But the doors opened inwards and the pressure of the terrified crowd simply forced them ever more tightly shut. Within ten minutes, the entire church, which was constructed almost entirely out of wood and pine tar, became an inferno. That day over one hundred people met, as the magazine described it, “a most melancholy end”, burning to death in what is still the most catastrophic fire in Norwegian history.

Only a few people survived. They did so by following the example of their preacher. For Pastor Iver Hesselberg did not join the rush toward the closed church doors. Instead, he jumped swiftly down from his pulpit and, with great practical purpose, began piling up Bibles under one of the high windows by the altar. Then, after scrambling up them to the relative security of the window ledge, he hurled himself through the leaded glass and out of the burning edifice to safety. Some might have called his actions selfish, but all over Europe newspapers praised the cool logic of the enterprising priest, who thought his way out of a crisis and did not succumb to the group stampede. Here was a man of his time, they wrote, a thinker: an individual who stood outside his flock. Grateful for his second chance in life, Pastor Hesselberg evolved into a philanthropist and public figure. A contemporary remembered him as “a strict man who preached fine sermons”, a staunch Lutheran who was also a liberal idealist, visiting the poor and teaching them arithmetic, as well as how to read and write. He even founded a parish library.

Hesselberg ended his days as a distinguished theologian and eventually a member of the Norwegian parliament, where he helped to ensure that all public buildings in Norway would in future be built with doors that opened outwards. His son, Hans Theodor, attempted to follow in his footsteps. He trained for the priesthood and married into one of Norway’s most distinguished families. His wife was a descendant of Peter Wessel, a Norwegian naval hero, who had been killed in a duel in 1720.

They settled at Vaernes,* (#ulink_5557ab62-58d3-5fe3-aa1c-58e1c4f20700) a large farm not far from Trondheim, the ancient capital of Norway, whose magnificent Romanesque cathedral, built on the shrine of Norway’s patron saint, St Olave, almost a millennium ago, evokes a virtually forgotten age when Scandinavia was a key spiritual centre of Christian Europe.

In Vaernes, Hans Theodor raised eleven children, but he lacked his father’s shrewd judgement and talent for hard work. He drank excessively, managed his estates incompetently, and never practised as a priest. He was also an incorrigible — and unsuccessful — gambler. Bit by bit, he was forced to sell off his lands to pay his gaming debts. One evening he went too far. He staked the village storehouse in a game of cards and lost. Outraged at this disregard for his responsibilities to his flock, the local community forced him to sell what remained of the farm. Hans Theodor moved to Trondheim, where he died a pauper in 1898.

But his children went out into the world and prospered — many entering the burgeoning Norwegian middle classes. Two became merchants, one became an apothecary, another a meteorologist. Yet another, Karl Laurits, trained as a scientist, then studied law and eventually went to work in Christiania, now Oslo, as an administrator in the Norwegian Public Service Pension Fund. In 1884 he married Ellen Wallace, and the following year, his first daughter, Sofie Magdalene, was born in Kristiania.† (#ulink_01bea79e-0ed3-5e30-9e8e-ca6778521fc2) Thirty-one years later, on a crisp autumn day in South Wales, she would give birth to her only son, Roald.

Roald Dahl himself was not that interested in his ancestry or in historical detail. Though proud of his Norwegian roots, archives and public records were not his domain, and when, in his late sixties, he wrote his own two volumes of memoirs, Boy and Going Solo, he seems to have known nothing of his great-great-grandfather Hesselberg’s extraordinary escape from the church fire or of the streak of reckless gambling and alcohol addiction that had emerged in his descendants.

Yet Pastor Hessel-berg’s story would almost certainly have fascinated Roald. He would have admired his ancestor’s resourceful ingenuity, as well as his ability to think both laterally and practically in the face of a crisis. These were qualities he admired in others and they were attributes he gave to the heroes and heroines of many of his children’s books. In his own life, too, Dahl would face many moments of crisis and struggle, and seldom were his resources of tenacity or inventiveness found wanting. His psychology and philosophy was always positive. “Get on with it,” was one of his favourite phrases, recommended to family, friends and colleagues alike, and one that he put into practice many times in his life when dealing with adversity — whether that was accident, war, injury, illness, depression or death. Like Pastor Hesselberg, he seldom looked behind him. He infinitely preferred to look forward.

Yet this was only one side of the man. His daughter Ophelia once described her father to me as “a pessimist by nature”,

and a depressive streak ran through both sides of his family. Many of his adult stories revealed a jaundiced and sometimes bleak view of human behaviour, which drew repeatedly on man’s capacity for cruelty and insensitivity. His children’s writing is sunnier, more positive — though even there, early critics complained of tastelessness and brutality.

It was a charge against which he always energetically defended himself, for underneath the exterior of the humourist and entertainer lurked a fierce moralist. But he found it hard because, like many writers, he hated analysing his own writing. I remember asking him on camera why so many of the central characters in his children’s stories had lost one or both parents. He was taken aback by the question and at first even denied that this was the case. However, when, on reflection, he realized that he had made a mistake, his brain searched swiftly for a way out. He compared himself to Dickens. He had used “a trick”, he said, “to get the reader’s sympathy”. In a rare confession of error, he admitted with a smile that he “had been caught out a bit”.

What struck me most profoundly was that he seemed to make no conscious connection between his own life — he had lost his own father when he was three years old — and the worlds he created in his stories. It suggested, I thought, a kind of unexpected innocence and naivety.

Dahl’s writing career would take many twists and turns over the course of his seventy-four years, and these convolutions were intimately bound up with a complex private life that held many hidden corners, secrets and anxieties. Together they made a powerful cocktail — for Dahl was full of contradictions and paradoxes. He loved the privacy of his writing hut, yet he liked to be in the public eye. He described himself as a family man, living in a modest English village, yet he was married to an Oscar-winning movie star, and kept the company of presidents and politicians, diplomats and spies. He was fascinated by wealth and glamour. He often bragged. He gambled. He had a quick and discerning eye for great art and craftsmanship. He was drawn to the good things in life. Yet he was also a simple man, who preferred the Buckinghamshire countryside to life in the city — a man who grew fruit, vegetables and orchids with obsessive passion, who surrounded himself with animals, who bred and raced greyhounds, and who kept the company of tradesmen and artisans. He was generous, although his kindness was usually quiet and low key. Often only the recipient was aware of it. Roald himself however was no shrinking violet. He enjoyed public appearances, and delighted in being controversial. He was a conundrum. An egotistical self-publicist — notoriously brash, even oafish, in the limelight — he could also behave as slyly as the foxes he so admired. If he wanted, he could cover his tracks and go to ground.

As a writer, he was the most unreliable of witnesses — particularly when he spoke or wrote about himself. In Boy, his own evocative and zestful memoir of childhood, he begins by disparaging most autobiography as “full of all sorts of boring details.”

His book, he asserts, will be no history, but a series of memorable impressions, simply skimmed off the top of his consciousness and set down on paper. These vignettes of childhood are painted in bold colours and leap vividly off the page. They are infused with detail that is often touching, and always devoid of sentiment. Each adventure or escapade is retold with the intimate spirit of one child telling another a story in the playground. The language is simple and elegant. Humour is to the fore. Self-pity is entirely absent. “Some [incidents] are funny. Some are painful. Some are unpleasant,” he declares of his memories, concluding theatrically: “All are true.” In fact, almost all are, to some extent, fiction. The semblance of veracity is achieved by Dahl’s acute observational eye, which adds authenticity to the most fantastical of tales, and by a remarkable trove of 906 letters he kept at his side as he wrote. These were letters he had written to his mother throughout his life, and which she hoarded carefully, preserving them through the storms of war and countless changes of address.

In these miniature canvases, Dahl began to hone his idiosyncratic talent for interweaving truth and fiction. It would be pedantic to list the inaccuracies in Boy or its successor Going Solo. Most of them are unimportant. A grandfather confused with a great-grandfather, a date exaggerated, a slip in chronology, countless invented details. Boy is a classic, not because it is based on fact but because Dahl had a genius for storytelling. Yet its untruths, omissions and evasions are revealing. Not only do they disclose the author’s need to embellish, they hint as well at the complex hidden roots of his imagination, which lay tangled in a soil composed of lost fathers, uncertain friendships, a need to explore frontiers, an essentially misanthropic view of humanity, and a sense of fantasy that stemmed in large part from the Norwegian blood that ran powerfully through his veins.

Norway was always important to Dahl. Though he would sometimes surprise guests at dinner by maintaining garrulously that all Norwegians were boring, he never lost his profound affection for and bond with his homeland. His mother lived in Great Britain for over fifty years, yet never renounced her Norwegian nationality, even though it sometimes caused her inconvenience — most notably when she had to live as an alien in the United Kingdom during two world wars. Although she usually spoke to her children in English and always wrote to them in her adopted language, she made sure they also learned to speak Norwegian at the same time they were learning English; and every summer she took them to Norway on holiday. Forty years later, Roald would recreate these summer holidays for his own children, reliving memories that he would later immortalize in Boy. “Totally idyllic,” was how he described these vacations. “The mere mention of them used to send shivers of joy rippling all over my skin.”

Part of the pleasure was, of course, an escape from the rigors of an English boarding school, but for Roald the delight was also more profound. “We all spoke Norwegian and all our relations lived over there,” he wrote in Boy. “So, in a way, going to Norway every summer was like going home.”

“Home” would always be a complex idea for him. His heart may have sometimes felt it was in Norway, but the home he dreamed about most of the time was an English one. During the Second World War, when he was in Africa and the Middle East as a pilot and in Washington as a diplomat, it was not Norway he craved for, nor the valleys of Wales he had loved as a child, but the fields of rural England. There, deep in the heart of the Buckinghamshire countryside, he, his mother and his three sisters would later construct for themselves a kind of rural enclave: the “Valley of the Dahls”, as Roald’s daughter Tessa once described it. Purchasing homes no more than a few miles away from each other, the family lived, according to one of Roald’s nieces, “unintegrated … and largely without proper English friends”.