Полная версия:

Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Mother and a Daughter in the ‘Gilded Age’

CONSUELO

& ALVA

VANDERBILT

The Story of a Mother and Daughter in the Gilded Age

Amanda Mackenzie Stuart

To my daughters, Daisy and Marianna

Contents

Cover

Title page

PREFACE

Prologue

PART ONE

1: The family of the bride

2: Birth of an heiress

3: Sunlight by proxy

4: The wedding

PART TWO

5: Becoming a duchess

6: Success

7: Difficulties

PART THREE

8: Philanthropy, politics and power

9: Old tricks

10: Love, philanthropy and suffrage

PART FOUR

11: A story re-told

12: French lives

13: Harvest on home ground

Afterword

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PRAISE

Copyright

About the publisher

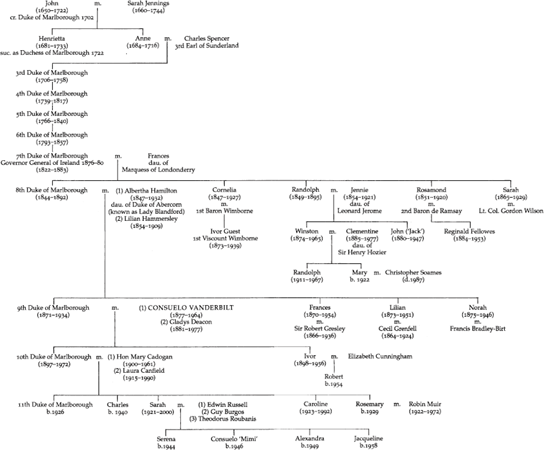

Select Family Tree of the Spencer-Churchills mentioned in the text

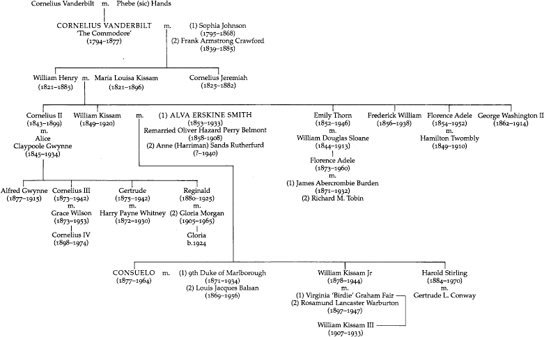

Select Family Tree of the Vanderbilts mentioned in the text

PREFACE

This book began with a story. Some time ago, I took my eighteen-year-old daughter and a young Australian friend to visit Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, in order that the young Australian could have a glimpse of English ‘heritage’ before she went home. The guides at Blenheim Palace are free to talk about its history as they please, but there is one tale which engages visitors powerfully – the story of Consuelo Vanderbilt, an American heiress said to have been compelled by her socially ambitious mother to marry the 9th Duke of Marlborough in 1895, bringing a generous Vanderbilt dowry to an English palace sorely in need. Anyone wandering through the state rooms of Blenheim soon encounters two very different portraits of Consuelo. The first, by Carolus-Duran, was painted when she was seventeen against a classical English landscape and suggests an enigmatic but dynamic young woman, as yet little more than a girl. The second portrait, far more uneasy and much more famous, was painted eleven years later by John Singer Sargent. Here, Consuelo and the 9th Duke have been placed in their historical context beneath a bust of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, but at a distance from each other. Each inhabits a markedly private space linked only by their eldest son. Neither looks happy; but while the Duke gazes steadily outwards, Sargent has painted Consuelo glancing anxiously to one side with a striking air of melancholy.

It soon became apparent that our guide had little time for the 9th Duke. ‘This is Sunny,’ she said, gesturing at the Sargent portrait. ‘Sunny by name but most certainly not Sunny by nature.’ She glared severely at my daughter. ‘Consuelo was your age when she came to Blenheim. You’re probably still at school. But she got out in the end. Thank Heavens.’

Afterwards, the young Australian professed to be enthralled by English heritage, so we moved on to the nearby church of St Martin in Bladon, where Winston Churchill is buried in the churchyard with other members of the Spencer-Churchill family. Since his death, relatives buried alongside him have thoughtfully been redefined so that visitors can understand the relationship with Churchill at a glance. In one grave in the corner of the plot, however, an inscription reads: ‘Consuelo Vanderbilt wife of the ninth Duke.’ On the other side, her headstone is inscribed: ‘In loving memory of Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan – mother of the tenth Duke of Marlborough – born 2nd March 1877 – died 6th December 1964.’

This was startling. Consuelo had clearly remarried. So why had she come back? Surely no-one had compelled her to burial in a Bladon churchyard, even if she had been forced to Blenheim Palace in life? This puzzle was soon replaced by another. Limited research revealed that there were writers who rejected the allegation that Consuelo had been forced to marry the Duke and there were those, even in her lifetime, who asserted the story was a flat lie. This was followed by a further conundrum. It emerged that Consuelo’s mother, Alva, villainess-in-chief, eventually became a leader in the fight for women’s suffrage in America. How could anyone square even rudimentary feminism with ordering her daughter to marry a duke? One writer suggested she might have undergone a conversion to suffragism as an act of penance, but even on superficial acquaintance, Alva Belmont (as she later became) did not seem the penitential type.

It soon became clear that an account of what had happened and why would have to explore Alva’s life as well as Consuelo’s but there were further complications. The story of Consuelo’s first marriage had inspired others, notably Edith Wharton’s last (unfinished) novel, The Buccaneers. There were obstacles in the way of non-fiction, however. Consuelo and Alva left few private papers, and surviving sources were far from impartial. Both made attempts at autobiography. Consuelo’s memoir The Glitter and the Gold was published in 1952. Alva started her memoirs twice, once in 1917 and again after 1928, but neither version was completed. At the same time, the lives of both women were frequently the subject of comment in the press. Alva in particular encouraged this and intermittently attempted to influence and re-edit press narratives, including those relating to Consuelo. Mother and daughter spent a considerable part of their later lives thousands of miles apart, separated by the Atlantic, and both eventually preferred to be defined by events and activities beyond Consuelo’s life as Duchess of Marlborough. In spite of these difficulties, however, their lives prove more illuminating side-by-side than taken singly. They continued to influence each other; their interests and tastes eventually converged; and they found themselves defined and bound together for ever by the story of Consuelo’s first marriage.

Prologue

IN NOVEMBER 1895, shortly before the New York wedding of Consuelo Vanderbilt to the 9th Duke of Marlborough, her cousin Gertrude raged at her journal about the unhappy lot of heiresses. ‘You don’t know what the position of an heiress is! You can’t imagine,’ she wrote, nib scratching paper with anger. ‘There is no one in all the world who loves her for herself. No one. She cannot do this, that and the other simply because she is known by sight and will be talked about … the world points at her and says “watch what she does, who she likes, who she sees, remember she is an heiress,” and those who seem to forget this fact are those who really remember it most vividly.’1

Had she been in a position to read her cousin’s journal, Miss Consuelo Vanderbilt would have agreed, for the world she knew was certainly watching and pointing. In the days leading up to 6 November 1895, preparations for her wedding dominated the front pages of New York’s popular newspapers, relegating to second, third and fourth place the advancing popularity of bloomers as cycling dress, New York State elections and a war of independence in Cuba. One newspaper, the New York World, led the field in examining the bride-to-be, providing its readers with a helpful list of her most important characteristics:

Age: Eighteen years Chin: Pointed, indicating vivacity Color of hair: Black Color of eyes: Dark brown Eyebrows: Delicately arched Nose: Rather slightly retroussé Weight: One hundred and sixteen and one half pounds Foot: Slender, with arched instep Size of shoe: Number three. AA last Length of foot: Eight and one half inches Length of hand: Six inches Waist measure: Twenty inches Marriage settlement: $10,000,000 Ultimate fortune: $25,000,000 (estimated).2

As wedding preparations entered the final phase, a few enterprising passers-by near St Thomas Episcopalian Church on Fifth Avenue managed to peep in at the construction of the most spectacular wedding floral display ever assembled in a New York church: great flambeaux of pink and white roses on feathery palms at the end of pews; vaulting arches of asparagus fern, palm foliage and chrysanthemums; orchids suspended from the gallery; vines wound round the organ columns; floral gates constructed from small pink posies; and sweeping strands of lilies, ivy and holly swaggering from dome to floor, feats of festooning over 95-feet long. There was no shortage of other detail available for those with insufficient initiative – or interest – to seek it out for themselves. The press even provided lingering descriptions of the bridal underwear: ‘It is delightful to know that the clasps of Miss Vanderbilt’s stocking supporters are of gold, and that her corset-covers and chemises are embroidered with rosebuds in relief,’ said the society magazine Town Topics. ‘If the present methods of reporting the movements and details of the life and clothes of these young people are pursued until the day of the wedding, I look for some revelations that would startle even a Parisian café lounger.’3

On the morning of 6 November, it was soon apparent that uninhibited staring was the order of the day. The wedding was at noon. At 72nd Street and Madison, where the bride was dressing at her mother’s house, the crowds started to gather before 9 a.m. and soon lined the entire route to St Thomas Church, twenty blocks away at 53rd Street and Fifth Avenue. At 72nd Street no-one was allowed within a hundred and fifty feet of Alva Vanderbilt’s new home, but all kinds of tactics were deployed by certain individuals determined to subvert the rules. By 10.30 a.m. the crowd had grown to around two thousand people, and windows in every house in the neighbourhood were crammed with spectators enjoying small private parties of their own. Curiosity was not confined to the common herd. Gertrude Vanderbilt’s outburst at the manner in which heiresses were watched was more than vindicated for lorgnettes were much in evidence and The New York Times noted that halfway down the block towards Park Avenue, women could be seen standing in bay windows peering out through opera glasses for glimpses of the bridal party.4

As the morning wore on, crowd control outside St Thomas Church became increasingly difficult. Reporters fell back on military metaphor. Acting Inspector Cartwright was in overall command of forces; Captain Strauss was deployed with his platoon at the home of the bride; further detachments were stationed by the church preventing incursions on the left flank; and all faced a difficult and unpredictable enemy. ‘Picture to yourself a space 15-feet wide and 100-feet long,’ said the New York World, ‘tightly packed with young women, old women, pretty women, ugly women, fat women, thin women – all struggling and pushing and squeezing to break through police lines. Then imagine all those women quarrelling one with another, then struggling and pushing and squeezing and begging, imploring, threatening and coaxing the police to let them pass.’5

The most pressing problem for Inspector Cartwright was that some of the women came from good homes which put him in an invidious position and obliged him to give orders that clubs should not be used. ‘Had you seen those policemen pressed to desperation turn and push that throng back inch by inch, half crushing an arm here, poking a waist or a neck there, collecting three women in an armful and hurling them back, the crowd would have reminded you of nothing so much as an obstreperous herd of cattle,’ said one reporter.6

There were compelling reasons for such intense curiosity. In an age of international marriages, of trade between American money and European titles, this was the grandest. The New York World went straight to the point: ‘Miss Consuelo Vanderbilt is one of the greatest heiresses in America. The Duke of Marlborough is probably the most eligible peer in Great Britain … From the standpoint of Fifth Avenue it will be the most desirable alliance ever made by an American heiress up to date.’7 The engagement was presented by others as an all-American tale that held out hope for everyone, even the poorest. ‘The world is actively engaged in making its fortune,’ said Frank Lewis Ford in an article in Munsey’s Magazine. ‘Though sometimes it calls the task by another name and says that it is earning its living, acquiring a competency, building up a business, or what not. And there stand the Vanderbilts, with living earned, competency acquired, business built up, fortune made.’8

But to those in the know – and there were many people in the know thanks to the nature of the press in late-nineteenth-century New York – this was all too simple. The newspapers buzzed with rumours. Was it true that this wedding would break the heart of at least one eligible American bachelor? Was the English Duke simply marrying the eighteen-year-old bride for her money? And where were the Vanderbilts? Was it really possible that none of them had been invited? In America in the 1890s the lives of the very rich provided community entertainment supplanted later by cinema and television. This wedding alone was a soap opera with enough story lines to satisfy the most avid audience, laced with the faint but thrilling possibility of further drama at the church door. Might the eligible bachelor appear? Would rogue Vanderbilts attempt to force an entry? Could there be a misguided attempt to kidnap Consuelo to prevent her from marrying a blackguard, and stop her fortune from leaving the country? It was certainly worth waiting around to find out.

The wedding guests seemed just as determined to make the most of the occasion as the crowd. Some of them arrived as early as 10 a.m., a full two hours before the ceremony was due to start. This presented the embattled Inspector Cartwright with another headache because those in the crowd who had arrived early to obtain a good vantage point now refused to make way for the wedding guests, and had to be forced back inch by inch across the street. The guests, meanwhile, were required to dismount from their carriages and make their way to the church on foot. Here there were further difficulties, for the doors of the church were still tightly closed, creating a genteel but tense scrum as the ton barged each other out of the way. When St Thomas Church finally opened its doors, the gentlemen ushers, selected by Alva for their experience in seating guests at weddings, had to call for police reinforcements. The guests rushed past the sexton, whose task it was to match invitations to faces and expel interlopers. They ignored the efforts of the ushers to place them according to Mrs Vanderbilt’s list. Some of them (women again) climbed over the floral decorations, deposited themselves in the central aisle reserved for the guests of honour and were only removed to less prestigious seating by the gentlemen ushers with the utmost difficulty. Others stood on their pews to peer at fellow guests over the foliage – the floral display was widely held to be a great success but it undeniably obscured the sight lines.

Inside the church, official entertainment began with an organ recital from Dr George Warren, as sixty members of Walter Damrosch’s Symphony Orchestra moved into their desks. From 11 a.m., the orchestra played through a musical equivalent of the floral display in a programme at which even commercial classical radio stations might now baulk: the Prize Song from Wagner’s Die Meistersingers; the Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin; Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3; Tchaikovsky’s Andante Cantabile String Quartet; the Grand March from Wagner’s Tannhauser; Fugue in G Minor by Bach; and the Overture to A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream by Mendelssohn, all in the space of fifty-five minutes. Fifty members of the choir took their seats in the choir stalls, together with four distinguished New York soloists, and the guests of honour began to appear.

Mrs Astor arrived first with Mr and Mrs John Jacob. She was escorted to her seat by Reginald Ronald and looked particularly splendid in a costume of grey completed by a velvet coat and a black toque with white satin rosettes. Mrs William Jay, close friend of Mrs Vanderbilt, followed closely behind with Colonel Jay, wearing one of the most ‘effective’ costumes of the wedding – a heavy black silk skirt, cut very full and with a bodice of yellow and crimson satin. A peal of church bells announced the arrival of the mother-of-the-bride, Alva Vanderbilt, with the bridesmaids. Miss Duer, Miss Morton, Miss Winthrop, Miss Burden, Miss Jay, Miss Goelet and Miss Bronson were ‘all exceedingly pretty young women’ gushed the reporter in charge of bridesmaids for The New York Times.9 They wore gowns of ivory satin, with magnificent broad-brimmed velvet hats, topped with ostrich feathers, and around-the-throat bands of blue velvet with over-strings of pearls. All heads swivelled as Mrs Vanderbilt came up the aisle, accompanied by the bride’s brothers, Willie K. Jr and Harold. She was wearing a gown of pale blue satin edged with sable, a hat of lace and silver with a pale blue aigrette, and had ‘a decided look of satisfaction on her face’.10

Alva Vanderbilt’s smug expression was not to last. Her arrival signalled the imminent appearance of the bride, escorted by her father, William K. Vanderbilt. A row of fashionable bishops appeared from the vestry room and took their places in the chancel. The Duke of Marlborough, who had slipped into St Thomas Church unnoticed with his best man, Ivor Guest, took up his position and waited, incidentally giving the wedding guests a good opportunity to stare at him instead. One of them told a newspaper that ‘some of the guests partially rose in their seats to have a better view of the Lord of Blenheim. Some were asking where his relatives were and others answered that they were represented by the British Embassy.’11 This was true – the groom’s side was represented by the British ambassador, supported by two gentlemen from the embassy in Washington, Bax Ironsides and Lord Westmeath.

Along the New York streets and in St Thomas Church they waited. The ushers sauntered up to their stations, three on one side of the central aisle and three on the other – then sauntered back to the church porch again. Mr Damrosch, who had completed his concert programme, beat time with his baton in silence, his head turned round towards the church door. The Duke of Marlborough began to fidget nervously, and only regained some of his composure when he noted the English sang-froid of his best man. As the delay lengthened, the guests shuffled and whispered. Alva was observed looking uncharacteristically worried. And then decidedly strained. Five minutes passed … then ten … then twenty … and still the bride had not appeared.

1 The family of the bride

AS THE DELAY LENGTHENED and nervousness grew, self-appointed society experts in the crowd had time to debate one important question: had anyone seen the Vanderbilt family, whose apotheosis this was alleged to be? There could be no dispute that Vanderbilt gold was a powerful chemical element at work in St Thomas Church on 6 November 1895. It had given the bride her singular aura; it had drawn a duke from England; and without it, Alva would not now be waiting anxiously for her daughter to arrive. Scintillae of Vanderbilt gold dust brushed everything on the morning of Consuelo’s wedding, from the fronds of asparagus fern to the glinting lorgnettes in the crowd outside. It was remarkable, therefore, that apart from the father-of-the-bride, its chief purveyors should be so conspicuously absent; and even more striking that this scarcely mattered because of the force of character of the bride’s Vanderbilt great-grandfather, whose ancestral shade still hovered over the players in the morning’s drama as if he were alive.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, founder of the House of Vanderbilt, lingered in the collective memory partly because he laid down the basis of the family’s extraordinary wealth; and partly because of the robust manner in which he did it. He died in 1877, a few weeks before Consuelo was born, but he left a complex legacy and no examination of the lives of Alva and Consuelo is complete without first exploring it.

Fable attached itself to Cornelius Vanderbilt, known as ‘Commodore’ Vanderbilt, Head of the House of Vanderbilt, even in his lifetime. He generally did little to discourage this, but one misconception that irritated him was that the Vanderbilts were a ‘new’ family and he embarked on genealogical research to prove his point. However, he held matters up for several years by placing an advertisement in a Dutch newspaper in 1868 which read: ‘Where and who are the Dutch relations of the Vanderbilts?’, causing such offence that none of the Dutch relations could bring themselves to reply.1

More tactful experts later traced the Vanderbilts’ roots back to one Jan Aertson from the Bild in Holland who arrived in America around 1650. A lowly member of the social hierarchy exported by the Dutch West India Company, Jan Aertson Van Der Bilt worked as an indentured servant to pay for his passage and then acquired a bowerie or small farm in Flatbush, Long Island. His descendants traded land from Algonquin Indians on Staten Island, starting a long association between the Vanderbilts and the Staten Island community of New Dorp. They also joined the Protestant Moravian sect, whose members fled from persecution in Europe in the early-eighteenth century and settled nearby. The Vanderbilt family mausoleum is to be found at the peaceful and beautiful Moravian cemetery at New Dorp on Staten Island to this day.2

In a development that goes against the grain of immigration success stories, the Vanderbilt family arrived in America early enough to suffer a downturn in its fortunes in the mid-eighteenth century. Just at the point when the Staten Island farm became prosperous, it was repeatedly sub-divided by inheritance and by the time the Commodore was born in 1794, his father was scratching a subsistence living on a small plot, and ferrying vegetables to market on a periauger, a flat-bottomed sailing boat evolved from the Dutch canal scow. Historians of the family portray this Vanderbilt of pre-history as feckless and inclined to impractical schemes, but he compensated for his deficiencies by marrying a strong-minded, hard-working, frugal wife of English descent, Phebe Hands. Her family had also been ruined, by a disastrous investment in Continental bonds. They had nine children. The Commodore was their eldest son.

Circumstances thus conspired to provide the Commodore with what are now known to be many of the most common characteristics in the background of a great entrepreneur: a weak father and a ‘frontier mother’; a marked dislike of formal education (he hated school and spelt ‘according to common sense’); and a humble background.3 A humble background is almost mandatory in nineteenth-century American myth-making about the virtuous self-made man, but it was a characteristic the Commodore genuinely shared with others such as John Jacob Astor, Alexander T. Stewart and Jay Gould. After his death the Commodore was accused of being phrenologically challenged with a ‘bump of acquisitiveness’ in a ‘chronic state of inflammation all the time’, but he was not alone in finding that childhood poverty and near illiteracy ignited a very fierce flame.4 More unusually for a great entrepreneur, the Commodore was neither small nor puny. He developed enormous physical strength, accompanied by strong-boned good looks, a notorious set of flying fists and a streak of rabid competitiveness. Charismatic vigour, combined with a lurking potential for violence, made him a force to be reckoned with from an early age and even as a youth he developed a reputation for epic profanity and colourful aggression that never left him.