Полная версия:

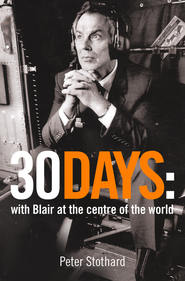

30 Days: A Month at the Heart of Blair’s War

30 DAYS

A Month at the Heart of Blair’s War

PETER STOTHARD

Dedication

For Sally

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Before

Monday, 10 March

Tuesday, 11 March

Wednesday, 12 March

Thursday, 13 March

Friday, 14 March

Saturday, 15 March

Sunday, 16 March

Monday, 17 March

Tuesday, 18 March

Wednesday, 19 March

Thursday, 20 March

Friday, 21 March

Saturday, 22 March

Sunday, 23 March

Monday, 24 March

Tuesday, 25 March

Wednesday, 26 March

Thursday, 27 March

Friday, 28 March

Saturday, 29 March

Sunday, 30 March

Monday, 31 March

Tuesday, 1 April

Wednesday, 2 April

Thursday, 3 April

Friday, 4 April

Saturday, 5 April

Sunday, 6 April

Monday, 7 April

Tuesday, 8 April

Wednesday, 9 April

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Before

‘This is your fiftieth birthday present, Prime Minister,’ ‘ says Strategy Director Alastair Campbell as Tony Blair comes in through the Downing Street front door. ‘Peter Stothard is going to follow you everywhere you go for fifty days.’

The recipient of this gift looks as though almost anything would be better than having a writer at his side as he enters the most difficult days of his political life.

Campbell concedes with a wolfish grin, ‘Well, a month then. Thirty days.’

Tony Blair sighs. He had agreed a few weeks ago for a writer from The Times Magazine to be with him on the path to war with Iraq. These were extraordinary days. His fiftieth birthday was coming up soon. It had seemed like a good idea.

Like many good resolutions it does not seem so attractive now that it is time to put it into practice. Little is going right. He does not even know that he has thirty days left behind the black door of Number Ten.

Politicians do sometimes take the risk of inviting a journalist in ‘to see them as they really are’. This is only either when they need the publicity or when they have a high degree of control. But no Prime Minister, however confident, has ever before taken that risk.

Tony Blair decides to stick with his decision. He will have a closely observed record of his leadership in the war against Saddam Hussein. He does not know what the record will be. His ‘fly on the wall’ will be a former editor of The Times who supported his programme to become leader of the Labour Party in 1994 but did not support him in the 1997 election which brought him to power.

To have me with him for thirty days will not be like having a total stranger in the corner of the room. But neither will he have a lifelong political supporter with him, or even one who shares many of his views.

6 March 2003, the day Tony Blair invited his chronicler through the door, was no better than any other day at this time. Britain had become an angry country. Millions of voters, particularly young voters who five years before had hailed his ‘Cool Britannia’, were enraged that a Labour Prime Minister, a New Labour Prime Minister, the first Labour Prime Minister since 1979, seemed about to send bombers to the civilians of Baghdad.

Worse even than bombing Iraqis who had ‘never done the British any harm’ was bombing them at the behest of a ‘Daddy’s Boy’ American President. Britain, they shouted, should just let George Bush get on with fighting his father’s old enemy, Saddam Hussein.

Those who knew a bit of history recalled that another Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson in the 1960s, kept Britain out of America’ s Vietnam nightmare. Why couldn’t Tony Blair do the same?

The protesters knew that they had allies at the highest levels of the Labour government. Clare Short was a respected figure of the old Labour left. She had an official position in the Cabinet as International Development Secretary, and an unofficial position as the ‘conscience of the party’. She was said to be enraged at what was about to be done ‘in her name’.

The ‘Not in my Name’ slogan was on banners and T-shirts from Bristol to Dundee. A million people had marched in London. The Italians and the Spanish were marching. They too had leaders who backed George Bush when their voters did not.

Tony Blair’s first words in the Number Ten front hall were a complaint about how he could not get his message across. I doubt if I sounded very sympath etic. Politicians forever complain to editors that they are prevented by unseen powers, never themselves, from ‘getting their message across’.

Inside the building there was a rush of people on the move. We were about to go to Chile, whose President was suddenly a pivotal player in the attempts to swing the United Nations squarely behind the war.

I went back home for my passport, told the magazine that I would take the ‘fiftieth birthday’ assignment, and barely left Tony Blair’s home, office, advisers, officials and political life for the next month. In those thirty days he faced the most hostile attacks from his voters, his supporters and his party. He faced fierce opposition in Europe and he forged a controversial partnership with a President of the United States who seemed at first so unlike him in so many ways. He saw a personal and a political challenge ahead, and seized them both. A man who was once known as consensual, accommodating, even insecure at times, behaved as a man possessed of certainty. He used occasionally to talk about history with journalists. Now he had just given a newspaper interview in which he said that history would be his judge.

Events fell one upon the other with tumultuous speed. The fiftieth birthday was scarcely mentioned ever again. We never went to Chile. We did sit together while the Prime Minister ‘worked the phones’ with other leaders, spoke to envoys from around the world, was taken for buggy rides by George Bush at Camp David and repaid the hospitality, according to the strange ways of modern diplomacy, at a castle in Belfast.

We were together in Parliament as he prepared for the debate which nearly cost him his job – and also when he weighed his responsibility for those who, as a result, had lost their lives. For thirty days I was close by him at historic events – in the places where writers never are.

Monday, 10 March

Morning headlines … Minister threatens resignation from Blair Cabinet … Iraq attacks ‘fascist’ USA … French Foreign Minister flies to woo African Security Council members …

‘So they are all against me, is that it?’ Tony Blair is sitting back on a swivel chair in his ‘den’ with his finger on a list of names. Around him is his ‘team’, squashed on the sofas, leaning against the table, hungry-eyed on the silver fruit bowl, perching uncomfortably against a window into the Downing Street garden. An honest answer would be: ‘Yes, Prime Minister.’ Alastair Campbell does not say anything. The Director of Communications and Strategy does not need to.

Tony Blair knows already. He has asked Independent Television for an opportunity to counter the fears of women opposed to war, women like those who are today shouting outside his house that he is a traitor to the Labour cause, a killer of children and about to be a war criminal. He calls it his ‘masochism strategy’.

The ‘all against me’ question is no sign of paranoia. Virtually everyone who wants to speak to him this week is against him. The leaders of France and Germany, the leader of the House of Commons, the leading figures in the trade unions, about half his own MPs, including Cabinet Minister Clare Short, all oppose a war on Saddam Hussein.

The paper in front of him now, propped up on his desk between a banana and a picture of his three-year-old son Leo, is part of the challenge he has set himself to change minds. It lists the names and life stories of the women chosen for the television ‘war special’ tonight. If they were not ‘all against’ him, they would not be there.

‘There seems a lot of military?’ he queries.

‘Yeah, some of them lost sons in the last Gulf War; they don’t think we should have to be doing the same job again,’ says Campbell baldly. ‘And some have got husbands in Kuwait now. They’re worried that no one at home thinks the war is justified this time. They think that’s your fault.’

Campbell is a man who dominates a lot of space. He is seated on the arm of the sofa, the seat closest to the Prime Minister, in front of the tall blue leather doors which lead to the Cabinet Room. He speaks slowly, with a slight drawl, looking down at his mobile phone for news.

‘And there’s a girl from Australia who lost her boyfriend in the Bali bomb, and a woman whose husband is a human shield at one of Saddam’s power stations.’

The Prime Minister stares hard at the list, twisting it as though to find its weakest point. There is only the barest chance now that war can be avoided.

The vital need now, he says, is that everyone of good will, at home and abroad, keeps up the pressure on the Iraqi leader. He sounds humourless when he makes remarks like this. But he has a lot to be humourless about.

His International Development Secretary, Clare Short, has already left his ‘good will’ club. She has not only gone on the BBC and denounced his policy as ‘reckless, reckless, reckless’, an act which by normal rules in normal times should have put her out of her job; she even telephoned the BBC herself and asked for a platform from which to make her attack. She was not one of those Ministers tricked by a clever question from an interviewer late at night. She decided what she wanted to say, that she was prepared to be sacked for saying it, and, with only the briefest advance warning to Campbell, had said it.

The advice of the team to its boss was that he should not give her the satisfaction of martyrdom. She expresse d the worries of too many people outside. It would be too big a risk.

But the irritation inside Number Ten is about more than just another bit of ‘Old Labour vs New Labour’ feuding. Dissent on such a scale from the top of his own government is another diplomatic hindrance as well as a new political challenge to Tony Blair.

‘And how is the programme going to deal with Clare?’ he asks sharply.

‘They’re going to get her over with first,’ whispers Campbell, as though the very name were a curse. ‘But look at it this way,’ he goes on. ‘The bulletins are only going to want the stuff on her. So you can just keep the rest nice and general.’

Before facing the fray, Tony Blair faces the long mirror that fills the wall between the two windows onto his garden. It is hard to know what he sees. What his team sees is a man who is thinner-faced and darker-eyed than six months ago. What journalists see, and describe almost daily now, is a man under impossible pressure, whose skin colour testifies to sleepless nights and anxious days.

Officially, he has a cold, a virus ‘that won’t go away’. There is a make-up man outside waiting, whatever the cause of his troubles, to disguise their worst effects.

‘It’s all very well being a pacifist,’ the Prime Minister says suddenly, still with his back to his team. ‘But to be a pacifist after September 11, that’s something different. It’s all new now: terrible threat, terrorist weapons, terrorist states. That is what people here have to understand.’

For most of his political life Tony Blair has been trying to persuade believers in old ideas that they should embrace new ones. He has had great success. He has made an unelectable socialist party electable again. Clare Short has accused him not only of being ‘reckless with his own future’, but ‘reckless with his place in history’.

The Prime Minister says that he is not concerned with his own future. Some of those around him believe that. Some worry about it. But his place in history? That is plainly important to him. He is gambling his secure place in the history of British politics for a place in the history of the world.

He returns to the list. ‘How many anti-Americans?’

Campbell punches out a text-message on his phone in a manner suggesting that the answer is bloody obvious.

For the first time Jonathan Powell shows an interest. This boyish former Washing ton diplomat does not always seem as dominant as Campbell or as personally close to the Prime Minister as the blunt Political Director, Sally Morgan, currently propped against the front of the desk. But Powell is the Chief of Staff. Ten Downing Street is his domain. He does not want to talk about television programmes. He has United Nations problems, Chileans and Mexicans and a Security Council member in Africa whose leader is ill, can barely even be spoken to by telephone and may need a visit.

Tony Blair makes most diplomatic calls in this ‘den’. It is a small office full of family photographs, like the consulting room of a successful doctor.

Civil servants do not recall a Prime Minister who has sat at a desk and ‘worked the phones’ so much. He has been obsessive in trying to persuade world leaders that they should back the United Nations’ so-called ‘Second Resolution’ which authorises an automatic invasion of Iraq if Saddam Hussein does not disarm.

Whenever Tony Blair is firmly in control of a call, or is gently keeping a friendship warm, he has his feet up on the desk. If he has his head hunched forward, he is making a case that his hearer does not want to hear. In the past few days he has been more hunched than not.

A Prime Minister is overheard and watched over most of the time. Powell’s characteristic position is to be listening in from his desk outside, earpiece jammed to the side of his head, pushing against his curly black hair. He has to concentrate intently on every ‘Hi, George’ against the murmur of news from a flat-screen TV on the wall.

This is not yet time for an office sandpit and model tanks with flags. The prime and most pressing battlefield is still at the United Nations. The second battle is for public support, particularly from those groups who most hate what seems certain soon to happen. The third is for the support of Labour Members of Parliament.

In the mirror on the wall of the den the Prime Minister can see all the faces in the room. If there is a common feeling among his team apart from fatigue it is impatience. Nothing is going as planned. Tony Blair looks down at the fruit bowl, takes a green apple and chews it very slowly, as though obeying some half-remembered hints for health.

Campbell’s pager buzzes. He glances down and announces that an anti-war Conservative has just resigned over his party’s support for the government.

‘In fact he hasn’t just resigned. He decided to quit last Wednesday, but thought he’d keep back the news till a quieter day.’ Everyone laughs. The tension is relaxed. It may not be the sharpest piece of political irony, but it is a joke that the team can share.

Mocking Conservatives is where most people here began; and opportunities at the moment are scarce. If the French or the Russians frustrate the efforts at the UN, and if Clare Short’s cries inflame more Labour opposition, a victory in Parliament may be possible only with Opposition support. Tony Blair, for seven years the toast of his party, could soon be ‘toast’ – or even ‘history’, as Americans use that word.

The first words from the make-up man confirm every immediate fear. ‘I’ve just come from doing the women,’ he says, putting down his transparent plastic eyeliner case and flapping the sweat off his short-sleeved black shirt. ‘They’re very angry. They’ve been stuck in the room for ages. The camera lights are on and they’re very hot and …’ – he pauses to deliver what is, in his view, by far the worst sign of Prime Ministerial danger – ‘hardly any of them wear make-up.’

After Tony Blair’s forehead has been powdered for the cameras and the most analysed facial lines in Britain have been hidden beneath kindly ‘concealer’, he clarifies a few last points. ‘Shall I say anything about the UN timetable?’ The den is suddenly filled with overlapping cries of ‘wiggle room’, ‘full and immediate compliance’ and ‘dramatic change of mind by Saddam’.

‘Am I frustrated by Clare Short’s action, or distracted?’ he asks. This is just to fill time till the three-minute stage call. The coming ordeal may be in the Foreign Office Map Room, a hundred yards across the street. But this is theatre now. Campbell and Co. are the producers, wishing they had a better audience, cursing modern television for seeing ranters and emoters as the only ‘real people’ but helpless to do much about it. The bums are already on the seats. The star has to perform.

The ‘three minutes’ extends longer than would be allowed in the West End, almost up to rock-star levels of lateness. The Prime Minister is still at his desk, not so much ‘working the phones’ as being worked by them. There are anxious calls now not just from the White House but from Labour politicians, all of a seniority requiring a Prime Ministerial chat, all wanting to know ‘what Clare (and he) are bloody well up to’.

Clare Short today represents the fear and rage of many in the Prime Minister’s party who oppose war. She has also found new friends among marching voters who would not normally have the slightest sympathy with the Labour Party’s ‘conscience’ at all.

When Tony Blair has dealt with his last panicking colleague, his ‘security column’ eventually assembles in the hall behind the Number Ten Downing Street door. The decoration at this end is dull, almost domestic, by comparison with Cabinet Room and den. The black-and-white tiled floor is piled with refills for the fruit bowl, boxes of oranges, apples and bananas. This was originally the back entrance to the office, and it is still where the ‘Salisbury’s To You’ van comes.

The team goes ahead of its leader, ignoring shouts from reporters about his future. The Prime Minister is told to wait twenty seconds to let everyone else get out of his camera shot. The small patch of sky above is grey and cold. But by this stage he is reminded of the rising heat and sweat of his interrogators. He catches up quickly. ‘The boss didn’t want to wait,’ says the detective apologetically as together they all stride up to the room.

The Prime Minister steps gingerly over clumps of black cable. The ‘warm-up act’, the studio manager, who has used up all her usual jokes for entertaining guests, retreats in relief. The star of the afternoon apologises and is immediately assailed from all sides by women who do not believe him, do not trust him, and will never vote for him again. He hears the sound dreaded by any performer anywhere, violent volleys of slow handclapping. Portraits of Wellington and Nelson look down for an hour on a sight that neither of those great British heroes would have seen as very pretty.

‘No, it wasn’t very pretty,’ the inquest back in Downing Street agrees. The slow handclappers were a disgrace. Maybe ITV wouldn’t broadcast that bit.

OK, so probably they would. But there were only four slow-handers. And they were about as representative as a Socialist Workers’ circus. The presenter couldn’t control them. One woman was suspiciously expert on Yemen. Not even Nelson in his hero-of-the-Nile days could have handled the humidity. Had Blair thought when he first joined the Labour Party that he would end up sending B52s over Baghdad? What sort of question is that? And as for ‘I married a human shield,’ God help us.

Tony Blair seems the least bothered of anyone by the fiasco. At least no one will ever be able to say that he slunk in his bunker. He had to begin almost every answer with the phrase ‘I know I am not going to change your mind, but …’ He had a fresh powdering at each commercial break and would have benefited from more.

Why does he do it? That is what very few yet understand. This is not a place he would have been in five years ago. He would have hated the mockery and ridicule.

Ten years ago few of even his closest friends could imagine him in the place he is now. Tony Blair was not always the most certain of men. He had decent modern ideas for an almost dead party in Britain. He was persuasive and popular. He liked to persuade. He liked to be liked.

What has happened?

There are simple answers. He is taking the heat because he knows that he can. He has grown used to winning arguments, to winning elections, to defeating opposition in his party, to almost destroying his official Opposition in Parliament. He has discovered that he can absorb attack after attack and still be standing.

There are awkward answers. He is restless. He is realistic about how long political success ever lasts. He wants to get things done and get out. He does not want to look back later on missed chances to make his view of the world count. He is less patient than he was. A young fifty-year-old in a hurry? Rash? Reckless?

There are also the Christian beliefs that he shares not only with his family but with George Bush. These beliefs are powerfully held, sometimes publicly expressed, and appear to be an ever more important part of his life. They include a moral revulsion at how Saddam Hussein treats his own people. Religion in a British political leader makes everyone nervous. The team prefers not to talk about it.

Supporters and friends who remember the more diffident Tony Blair see a different Tony Blair today. Some love the ‘Mark 2’ version. Some hate it. Some have not yet noticed just how different it is.

Tony Blair won influence over George Bush with a gamble. He promised that British forces would be ready to fight alongside Americans against Saddam Hussein. He asked in return that the United States seek the maximum United Nations authority. It is not clear how precise the bargain was. But the gamble was made. Today it seems to be failing.

Limited United Nations support has been won. There has not been full support. The man who is accustomed to be a winner stands about to lose. He will be asked to make good on his pledge of troops without the UN backing he thought he could secure. He knows that George Bush will not wait long enough for the diplomats and persuaders to do everything that they want to do. This part of the battle is coming to an end.

He himself has recognised that reality but not yet fully faced it. He has not stopped being a persuader on TV and a diplomat on the telephone. He sees those arts as virtues in themselves. He may look like a long-distance runner, winding down in slow laps when the race is long over. He may seem like a once-famous actor, still working on a seaside pier. He will still keep arguing. He does not mind the rejection as much as he did. The ‘masochism strategy’ was well named.

Soon, however, he has to tear his mind away from unpersuadable voters and foreign leaders who have failed to live up to his hopes. He must move single-mindedly on to his own Members of Parliament. If he cannot persuade a majority of his own party, his promise of British troops will fall. He will be a young fifty-year-old looking for a new career earlier than he intended.