Полная версия

Полная версияThe Works of Robert Louis Stevenson – Swanston Edition. Volume 23

Believe me, dear Colvin, ever yours,

R. L. S.Yours came; the class is in summer; many thanks for the testimonial, it is bully; arrived along with it another from Symonds, also bully; he is ill, but not lungs, thank God – fever got in Italy. We have taken Cater’s chalet; so we are now the aristo’s of the valley. There is no hope for me, but if there were, you would hear sweetness and light streaming from my lips.

The Merry Men.

To W. E. Henley

Kinnaird Cottage, Pitlochry, July 1881.MY DEAR HENLEY, – I hope, then, to have a visit from you. If before August, here; if later, at Braemar. Tupe!

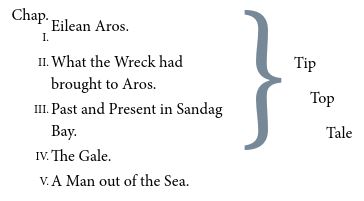

And now, mon bon, I must babble about The Merry Men, my favourite work. It is a fantastic sonata about the sea and wrecks. Chapter I. “Eilean Aros“ – the island, the roost, the “merry men,” the three people there living – sea superstitions. Chapter II. “What the Wreck had brought to Aros.” Eh, boy? what had it? Silver and clocks and brocades, and what a conscience, what a mad brain! Chapter III. “Past and Present in Sandag Bay“ – the new wreck and the old – so old – the Armada treasure-ship, Santma Trinid – the grave in the heather – strangers there. Chapter IV. “The Gale“ – the doomed ship – the storm – the drunken madman on the head – cries in the night. Chapter V. “A Man out of the Sea.” But I must not breathe to you my plot. It is, I fancy, my first real shoot at a story; an odd thing, sir, but, I believe, my own, though there is a little of Scott’s Pirate in it, as how should there not? He had the root of romance in such places. Aros is Earraid, where I lived lang syne;40 the Ross of Grisapol is the Ross of Mull; Ben Ryan, Ben More. I have written to the middle of Chapter IV. Like enough, when it is finished I shall discard all chapterings; for the thing is written straight through. It must, unhappily, be re-written – too well written not to be.

The chair is only three months in summer; that is why I try for it. If I get it, which I shall not, I should be independent at once. Sweet thought. I liked your Byron well; your Berlioz better. No one would remark these cuts; even I, who was looking for it, knew it not at all to be a torso. The paper strengthens me in my recommendation to you to follow Colvin’s hint. Give us an 1830; you will do it well, and the subject smiles widely on the world: —

1830: A Chapter of Artistic History, by William Ernest Henley (or of Social and Artistic History, as the thing might grow to you). Sir, you might be in the Athenæum yet with that; and, believe me, you might and would be far better, the author of a readable book. – Yours ever,

R. L. S.The following names have been invented for Wogg by his dear papa: —

Grunty-pig (when he is scratched),

Rose-mouth (when he comes flying up with his rose-leaf tongue depending), and

Hoofen-boots (when he has had his foots wet).

How would Tales for Winter Nights do?

To W. E. Henley

The spell of good health did not last long, and with a break of the weather came a return of catarrhal troubles and hemorrhage. This letter answers some criticisms made by his correspondent on The Merry Men as drafted in MS.

Pitlochry, if you please [August], 1881.Dear Henley, – To answer a point or two. First, the Spanish ship was sloop-rigged and clumsy, because she was fitted out by some private adventurers, not over wealthy, and glad to take what they could get. Is that not right? Tell me if you think not. That, at least, was how I meant it. As for the boat-cloaks, I am afraid they are, as you say, false imagination; but I love the name, nature, and being of them so dearly, that I feel as if I would almost rather ruin a story than omit the reference. The proudest moments of my life have been passed in the stern-sheets of a boat with that romantic garment over my shoulders. This, without prejudice to one glorious day when standing upon some water stairs at Lerwick I signalled with my pocket-handkerchief for a boat to come ashore for me. I was then aged fifteen or sixteen; conceive my glory.

Several of the phrases you object to are proper nautical, or long-shore phrases, and therefore, I think, not out of place in this long-shore story. As for the two members which you thought at first so ill-united; I confess they seem perfectly so to me. I have chosen to sacrifice a long-projected story of adventure because the sentiment of that is identical with the sentiment of “My uncle.” My uncle himself is not the story as I see it, only the leading episode of that story. It’s really a story of wrecks, as they appear to the dweller on the coast. It’s a view of the sea. Goodness knows when I shall be able to re-write; I must first get over this copper-headed cold.

R. L. S.To Sidney Colvin

The reference to Landor in the following is to a volume of mine in Macmillan’s series English Men of Letters. This and the next two or three years were those of the Fenian dynamite outrages at the Tower of London, the House of Lords, etc.

[Kinnaird Cottage, Pitlochry, August 1881.]MY DEAR COLVIN, – This is the first letter I have written this good while. I have had a brutal cold, not perhaps very wisely treated; lots of blood – for me, I mean. I was so well, however, before, that I seem to be sailing through with it splendidly. My appetite never failed; indeed, as I got worse, it sharpened – a sort of reparatory instinct. Now I feel in a fair way to get round soon.

Monday, August (2nd, is it?). – We set out for the Spital of Glenshee, and reach Braemar on Tuesday. The Braemar address we cannot learn; it looks as if “Braemar” were all that was necessary; if particular, you can address 17 Heriot Row. We shall be delighted to see you whenever, and as soon as ever, you can make it possible.

… I hope heartily you will survive me, and do not doubt it. There are seven or eight people it is no part of my scheme in life to survive – yet if I could but heal me of my bellowses, I could have a jolly life – have it, even now, when I can work and stroll a little, as I have been doing till this cold. I have so many things to make life sweet to me, it seems a pity I cannot have that other one thing – health. But though you will be angry to hear it, I believe, for myself at least, what is is best. I believed it all through my worst days, and I am not ashamed to profess it now.

Landor has just turned up; but I had read him already. I like him extremely; I wonder if the “cuts” were perhaps not advantageous. It seems quite full enough; but then you know I am a compressionist.

If I am to criticise, it is a little staid; but the classical is apt to look so. It is in curious contrast to that inexpressive, unplanned wilderness of Forster’s; clear, readable, precise, and sufficiently human. I see nothing lost in it, though I could have wished, in my Scotch capacity, a trifle clearer and fuller exposition of his moral attitude, which is not quite clear “from here.”

He and his tyrannicide! I am in a mad fury about these explosions. If that is the new world! Damn O’Donovan Rossa; damn him behind and before, above, below, and roundabout; damn, deracinate, and destroy him, root and branch, self and company, world without end. Amen. I write that for sport if you like, but I will pray in earnest, O Lord, if you cannot convert, kindly delete him!

Stories naturally at halt. Henley has seen one and approves. I believe it to be good myself, even real good. He has also seen and approved one of Fanny’s. It will make a good volume. We have now

Thrawn Janet (with Stephen), proof to-day.

The Shadow on the Bed (Fanny’s copying).

The Merry Men (scrolled).

The Body Snatchers (scrolled).

In germis

The Travelling Companion.

The Torn Surplice (not final title).

Yours ever,

R. L. S.To Dr. Alexander Japp

Dr. Japp (known in literature at this date and for some time afterwards under his pseudonym H. A. Page; later under his own name the biographer of De Quincey) had written to R. L. S. criticising statements of fact and opinion in his essay on Thoreau, and expressing the hope that they might meet and discuss their differences. In the interval between the last letter and this Stevenson with all his family had moved to Braemar.

The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar, Sunday [August 1881].MY DEAR SIR, – I should long ago have written to thank you for your kind and frank letter; but in my state of health papers are apt to get mislaid, and your letter has been vainly hunted for until this (Sunday) morning.

I regret I shall not be able to see you in Edinburgh; one visit to Edinburgh has already cost me too dear in that invaluable particular health; but if it should be at all possible for you to push on as far as Braemar, I believe you would find an attentive listener, and I can offer you a bed, a drive, and necessary food, etc.

If, however, you should not be able to come thus far, I can promise you two things: First, I shall religiously revise what I have written, and bring out more clearly the point of view from which I regarded Thoreau; second, I shall in the Preface record your objection.

The point of view (and I must ask you not to forget that any such short paper is essentially only a section through a man) was this: I desired to look at the man through his books. Thus, for instance, when I mentioned his return to the pencil-making, I did it only in passing (perhaps I was wrong), because it seemed to me not an illustration of his principles, but a brave departure from them. Thousands of such there were I do not doubt; still, they might be hardly to my purpose, though, as you say so, some of them would be.

Our difference as to pity I suspect was a logomachy of my making. No pitiful acts on his part would surprise me; I know he would be more pitiful in practice than most of the whiners; but the spirit of that practice would still seem to be unjustly described by the word pity.

When I try to be measured, I find myself usually suspected of a sneaking unkindness for my subject; but you may be sure, sir, I would give up most other things to be so good a man as Thoreau. Even my knowledge of him leads me thus far.

Should you find yourself able to push on to Braemar – it may even be on your way – believe me, your visit will be most welcome. The weather is cruel, but the place is, as I dare say you know, the very “wale” of Scotland – bar Tummelside. – Yours very sincerely,

Robert Louis Stevenson.To Mrs. Sitwell

The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar, [August 1881].… Well, I have been pretty mean, but I have not yet got over my cold so completely as to have recovered much energy. It is really extraordinary that I should have recovered as well as I have in this blighting weather; the wind pipes, the rain comes in squalls, great black clouds are continually overhead, and it is as cold as March. The country is delightful, more cannot be said; it is very beautiful, a perfect joy when we get a blink of sun to see it in. The Queen knows a thing or two, I perceive; she has picked out the finest habitable spot in Britain.

I have done no work, and scarce written a letter for three weeks, but I think I should soon begin again; my cough is now very trifling. I eat well, and seem to have lost but little flesh in the meanwhile. I was wonderfully well before I caught this horrid cold. I never thought I should have been as well again; I really enjoyed life and work; and, of course, I now have a good hope that this may return.

I suppose you heard of our ghost stories. They are somewhat delayed by my cold and a bad attack of laziness, embroidery, etc., under which Fanny had been some time prostrate. It is horrid that we can get no better weather. I did not get such good accounts of you as might have been. You must imitate me. I am now one of the most conscientious people at trying to get better you ever saw. I have a white hat, it is much admired; also a plaid, and a heavy stoop; so I take my walks abroad, witching the world.

Last night I was beaten at chess, and am still grinding under the blow. – Ever your faithful friend,

R. L. S.To Edmund Gosse

The Cottage (late the late Miss M’Gregor’s),Castleton of Braemar, August 10, 1881.MY DEAR GOSSE, – Come on the 24th, there is a dear fellow. Everybody else wants to come later, and it will be a godsend for, sir – Yours sincerely.

You can stay as long as you behave decently, and are not sick of, sir – Your obedient, humble servant.

We have family worship in the home of, sir – Yours respectfully.

Braemar is a fine country, but nothing to (what you will also see) the maps of, sir – Yours in the Lord.

A carriage and two spanking hacks draw up daily at the hour of two before the house of, sir – Yours truly.

The rain rains and the winds do beat upon the cottage of the late Miss Macgregor and of, sir – Yours affectionately.

It is to be trusted that the weather may improve ere you know the halls of, sir – Yours emphatically.

All will be glad to welcome you, not excepting, sir – Yours ever.

You will now have gathered the lamentable intellectual collapse of, sir – Yours indeed.

And nothing remains for me but to sign myself, sir – Yours,

Robert Louis Stevenson.N.B.– Each of these clauses has to be read with extreme glibness, coming down whack upon the “Sir.” This is very important. The fine stylistic inspiration will else be lost.

I commit the man who made, the man who sold, and the woman who supplied me with my present excruciating gilt nib to that place where the worm never dies.

The reference to a deceased Highland lady (tending as it does to foster unavailing sorrow) may be with advantage omitted from the address, which would therefore run – The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar.

To Edmund Gosse

The Cottage, Castleton of Braemar, August 19, 1881.If you had an uncle who was a sea captain and went to the North Pole, you had better bring his outfit. Verbum Sapientibus. I look towards you.

R. L. Stevenson.To Edmund Gosse

[Braemar, August 19, 1881.]MY DEAR WEG, – I have by an extraordinary drollery of Fortune sent off to you by this day’s post a P.C. inviting you to appear in sealskin. But this had reference to the weather, and not at all, as you may have been led to fancy, to our rustic raiment of an evening.

As to that question, I would deal, in so far as in me lies, fairly with all men. We are not dressy people by nature; but it sometimes occurs to us to entertain angels. In the country, I believe, even angels may be decently welcomed in tweed; I have faced many great personages, for my own part, in a tasteful suit of sea-cloth with an end of carpet pending from my gullet. Still, we do maybe twice a summer burst out in the direction of blacks – and yet we do it seldom. In short, let your own heart decide, and the capacity of your portmanteau. If you came in camel’s hair, you would still, although conspicuous, be welcome.

The sooner the better after Tuesday. – Yours ever,

Robert Louis Stevenson.To W. E. Henley

The following records the beginning of work upon Treasure Island, the name originally proposed for which was The Sea Cook: —

[Braemar, August 25, 1881.]MY DEAR HENLEY, – Of course I am a rogue. Why, Lord, it’s known, man; but you should remember I have had a horrid cold. Now, I’m better, I think; and see here – nobody, not you, nor Lang, nor the devil, will hurry me with our crawlers. They are coming. Four of them are as good as done, and the rest will come when ripe; but I am now on another lay for the moment, purely owing to Lloyd, this one; but I believe there’s more coin in it than in any amount of crawlers: now, see here, The Sea Cook, or Treasure Island: A Story for Boys.

If this don’t fetch the kids, why, they have gone rotten since my day. Will you be surprised to learn that it is about Buccaneers, that it begins in the “Admiral Benbow” public-house on Devon coast, that it’s all about a map, and a treasure, and a mutiny, and a derelict ship, and a current, and a fine old Squire Trelawney (the real Tre, purged of literature and sin, to suit the infant mind), and a doctor, and another doctor, and a sea cook with one leg, and a sea-song with the chorus “Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum” (at the third Ho you heave at the capstan bars), which is a real buccaneer’s song, only known to the crew of the late Captain Flint (died of rum at Key West, much regretted, friends will please accept this intimation); and lastly, would you be surprised to hear, in this connection, the name of Routledge? That’s the kind of man I am, blast your eyes. Two chapters are written, and have been tried on Lloyd with great success; the trouble is to work it off without oaths. Buccaneers without oaths – bricks without straw. But youth and the fond parent have to be consulted.

And now look here – this is next day – and three chapters are written and read. (Chapter I. The Old Sea-dog at the “Admiral Benbow.” Chapter II. Black Dog appears and disappears. Chapter III. The Black Spot.) All now heard by Lloyd, F., and my father and mother, with high approval. It’s quite silly and horrid fun, and what I want is the best book about the Buccaneers that can be had – the latter B’s above all, Blackbeard and sich, and get Nutt or Bain to send it skimming by the fastest post. And now I know you’ll write to me, for The Sea Cook’s sake.

Your Admiral Guinea is curiously near my line, but of course I’m fooling; and your Admiral sounds like a shublime gent, Stick to him like wax – he’ll do. My Trelawney is, as I indicate, several thousand sea-miles off the lie of the original or your Admiral Guinea; and besides, I have no more about him yet but one mention of his name, and I think it likely he may turn yet farther from the model in the course of handling. A chapter a day I mean to do; they are short; and perhaps in a month The Sea Cook may to Routledge go, yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum! My Trelawney has a strong dash of Landor, as I see him from here. No women in the story, Lloyd’s orders; and who so blithe to obey? It’s awful fun boys’ stories; you just indulge the pleasure of your heart, that’s all; no trouble, no strain. The only stiff thing is to get it ended – that I don’t see, but I look to a volcano. O sweet, O generous, O human toils. You would like my blind beggar in Chapter III. I believe; no writing, just drive along as the words come and the pen will scratch!

R. L. S.Author of Boys’ Stories.To Dr. Alexander Japp

This correspondent had paid his visit as proposed, discussed the Thoreau differences, listened delightedly to the first chapters of Treasure Island, and proposed to offer the story for publication to his friend Mr. Henderson, proprietor and editor of Young Folks.

[Braemar, September 1881.]MY DEAR DR. JAPP, – My father has gone, but I think I may take it upon me to ask you to keep the book. Of all things you could do to endear yourself to me, you have done the best, for my father and you have taken a fancy to each other.

I do not know how to thank you for all your kind trouble in the matter of The Sea Cook, but I am not unmindful. My health is still poorly, and I have added intercostal rheumatism – a new attraction – which sewed me up nearly double for two days, and still gives me a list to starboard – let us be ever nautical!

I do not think with the start I have there will be any difficulty in letting Mr. Henderson go ahead whenever he likes. I will write my story up to its legitimate conclusion; and then we shall be in a position to judge whether a sequel would be desirable, and I would then myself know better about its practicability from the story-teller’s point of view. – Yours ever very sincerely,

R. L. Stevenson.To W. E. Henley

This tells of the farther progress of Treasure Island, of the price paid for it, and of the modest hopes with which it was launched. “The poet” is Mr. Gosse. The project of a highway story, Jerry Abershaw, remained a favourite one with Stevenson until it was superseded three or four years later by another, that of the Great North Road, which in its turn had to be abandoned, from lack of health and leisure, after some six or eight chapters had been written.

Braemar, September 1881.MY DEAR HENLEY, – Thanks for your last. The £100 fell through, or dwindled at least into somewhere about £30. However, that I’ve taken as a mouthful, so you may look out for The Sea Cook, or Treasure Island: A Tale of the Buccaneers, in Young Folks. (The terms are £2, 10s. a page of 4500 words; that’s not noble, is it? But I have my copyright safe. I don’t get illustrated – a blessing; that’s the price I have to pay for my copyright.)

I’ll make this boys’ book business pay; but I have to make a beginning. When I’m done with Young Folks, I’ll try Routledge or some one. I feel pretty sure the Sea Cook will do to reprint, and bring something decent at that.

Japp is a good soul. The poet was very gay and pleasant. He told me much: he is simply the most active young man in England, and one of the most intelligent. “He shall o’er Europe, shall o’er earth extend.”41 He is now extending over adjacent parts of Scotland.

I propose to follow up The Sea Cook at proper intervals by Jerry Abershaw: A Tale of Putney Heath (which or its site I must visit): The Leading Light: A Tale of the Coast, The Squaw Men: or the Wild West, and other instructive and entertaining work. Jerry Abershaw should be good, eh? I love writing boys’ books. This first is only an experiment; wait till you see what I can make ’em with my hand in. I’ll be the Harrison Ainsworth of the future; and a chalk better by St. Christopher; or at least as good. You’ll see that even by The Sea Cook.

Jerry Abershaw – O what a title! Jerry Abershaw: d – n it, sir, it’s a poem. The two most lovely words in English; and what a sentiment! Hark you, how the hoofs ring! Is this a blacksmith’s? No, it’s a wayside inn. Jerry Abershaw. “It was a clear, frosty evening, not 100 miles from Putney,” etc. Jerry Abershaw. Jerry Abershaw. Jerry Abershaw. The Sea Cook is now in its sixteenth chapter, and bids for well up in the thirties. Each three chapters is worth £2, 10s. So we’ve £12, 10s. already.

Don’t read Marryat’s Pirate anyhow; it is written in sand with a salt-spoon: arid, feeble, vain, tottering production. But then we’re not always all there. He was all somewhere else that trip. It’s damnable, Henley. I don’t go much on The Sea Cook; but, Lord, it’s a little fruitier than the Pirate by Cap’n. Marryat.

Since this was written The Cook is in his nineteenth chapter. Yo-heave ho!

R. L. S.To W. E. Henley

Stevenson’s uncle, Dr. George Balfour, had recommended him to wear a specially contrived and hideous respirator for the inhalation of pine-oil.

Braemar, 1881.Dear Henley, with a pig’s snout onI am starting for London,Where I likely shall arrive,On Saturday, if still alive:Perhaps your pirate doctor mightSee me on Sunday? If all’s right,I should then lunch with you and with sheWho’s dearer to you than you are to me.I shall remain but little timeIn London, as a wretched clime,But not so wretched (for none are)As that of beastly old Braemar.My doctor sends me skipping. IHave many facts to meet your eye.My pig’s snout’s now upon my face;And I inhale with fishy grace,My gills outflapping right and left,Ol. pin. sylvest. I am bereftOf a great deal of charm by this —Not quite the bull’s eye for a kiss —But like a gnome of olden timeOr bogey in a pantomime.For ladies’ love I once was fit,But now am rather out of it.Where’er I go, revolted cursSnap round my military spurs;The children all retire in fitsAnd scream their bellowses to bits.Little I care: the worst’s been done:Now let the cold impoverished sunDrop frozen from his orbit; letFury and fire, cold, wind and wet,And cataclysmal mad reversesRage through the federate universes;Let Lawson triumph, cakes and ale,Whisky and hock and claret fail; —Tobacco, love, and letters perish,With all that any man could cherish:You it may touch, not me. I dwellToo deep already – deep in hell;And nothing can befall, O damn!To make me uglier than I am.R. L. S.This-yer refers to an ori-nasal respirator for the inhalation of pine-wood oil, oleum pini sylvestris.