Полная версия

Полная версияThe Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson — Volume 2

I must tell you, what I just remembered in a flash as I was walking about dictating this letter — there was in the original plan of the MASTER OF BALLANTRAE a sort of introduction describing my arrival in Edinburgh on a visit to yourself and your placing in my hands the papers of the story. I actually wrote it, and then condemned the idea — as being a little too like Scott, I suppose. Now I must really find the MS. and try to finish it for the E. E. It will give you, what I should so much like you to have, another corner of your own in that lofty monument.

Suppose we do what I have proposed about Fergusson's monument, I wonder if an inscription like this would look arrogant -

This stone originally erected by Robert Burns has been repaired at the charges of Robert Louis Stevenson, and is by him re-dedicated to the memory of Robert Fergusson, as the gift of one Edinburgh lad to another.

In spacing this inscription I would detach the names of Fergusson and Burns, but leave mine in the text.

Or would that look like sham modesty, and is it better to bring out the three Roberts?

Letter: TO R. A. M. STEVENSON

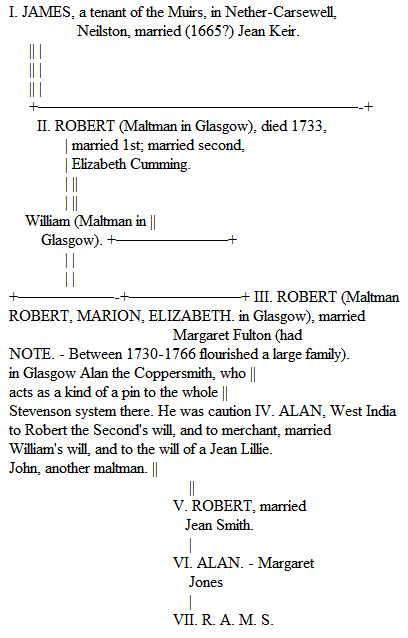

VAILIMA, JUNE 1894MY DEAR BOB, — I must make out a letter this mail or perish in the attempt. All the same, I am deeply stupid, in bed with a cold, deprived of my amanuensis, and conscious of the wish but not the furnished will. You may be interested to hear how the family inquiries go. It is now quite certain that we are a second-rate lot, and came out of Cunningham or Clydesdale, therefore BRITISH folk; so that you are Cymry on both sides, and I Cymry and Pict. We may have fought with King Arthur and known Merlin. The first of the family, Stevenson of Stevenson, was quite a great party, and dates back to the wars of Edward First. The last male heir of Stevenson of Stevenson died 1670, 220 pounds, 10s. to the bad, from drink. About the same time the Stevensons, who were mostly in Cunningham before, crop up suddenly in the parish of Neilston, over the border in Renfrewshire. Of course, they may have been there before, but there is no word of them in that parish till 1675 in any extracts I have. Our first traceable ancestor was a tenant farmer of Muir of Cauldwells — James in Nether-Carsewell. Presently two families of maltmen are found in Glasgow, both, by re-duplicated proofs, related to James (the son of James) in Nether Carsewell. We descend by his second marriage from Robert; one of these died 1733. It is not very romantic up to now, but has interested me surprisingly to fish out, always hoping for more — and occasionally getting at least a little clearness and confirmation. But the earliest date, 1655, apparently the marriage of James in Nether Carsewell, cannot as yet be pushed back. From which of any number of dozen little families in Cunningham we should derive, God knows! Of course, it doesn't matter a hundred years hence, an argument fatal to all human enterprise, industry, or pleasure. And to me it will be a deadly disappointment if I cannot roll this stone away! One generation further might be nothing, but it is my present object of desire, and we are so near it! There is a man in the same parish called Constantine; if I could only trace to him, I could take you far afield by that one talisman of the strange Christian name of Constantine. But no such luck! And I kind of fear we shall stick at James.

So much, though all inchoate, I trouble you with, knowing that you, at least, must take an interest in it. So much is certain of that strange Celtic descent, that the past has an interest for it apparently gratuitous, but fiercely strong. I wish to trace my ancestors a thousand years, if I trace them by gallowses. It is not love, not pride, not admiration; it is an expansion of the identity, intimately pleasing, and wholly uncritical; I can expend myself in the person of an inglorious ancestor with perfect comfort; or a disgraced, if I could find one. I suppose, perhaps, it is more to me who am childless, and refrain with a certain shock from looking forwards. But, I am sure, in the solid grounds of race, that you have it also in some degree.

Enough genealogy. I do not know if you will be able to read my hand. Unhappily, Belle, who is my amanuensis, is out of the way on other affairs, and I have to make the unwelcome effort. (O this is beautiful, I am quite pleased with myself.) Graham has just arrived last night (my mother is coming by the other steamer in three days), and has told me of your meeting, and he said you looked a little older than I did; so that I suppose we keep step fairly on the downward side of the hill. He thought you looked harassed, and I could imagine that too. I sometimes feel harassed. I have a great family here about me, a great anxiety. The loss (to use my grandfather's expression), the 'loss' of our family is that we are disbelievers in the morrow — perhaps I should say, rather, in next year. The future is ALWAYS black to us; it was to Robert Stevenson; to Thomas; I suspect to Alan; to R. A. M. S. it was so almost to his ruin in youth; to R. L. S., who had a hard hopeful strain in him from his mother, it was not so much so once, but becomes daily more so. Daily so much more so, that I have a painful difficulty in believing I can ever finish another book, or that the public will ever read it.

I have so huge a desire to know exactly what you are doing, that I suppose I should tell you what I am doing by way of an example. I have a room now, a part of the twelve-foot verandah sparred in, at the most inaccessible end of the house. Daily I see the sunrise out of my bed, which I still value as a tonic, a perpetual tuning fork, a look of God's face once in the day. At six my breakfast comes up to me here, and I work till eleven. If I am quite well, I sometimes go out and bathe in the river before lunch, twelve. In the afternoon I generally work again, now alone drafting, now with Belle dictating. Dinner is at six, and I am often in bed by eight. This is supposing me to stay at home. But I must often be away, sometimes all day long, sometimes till twelve, one, or two at night, when you might see me coming home to the sleeping house, sometimes in a trackless darkness, sometimes with a glorious tropic moon, everything drenched with dew — unsaddling and creeping to bed; and you would no longer be surprised that I live out in this country, and not in Bournemouth — in bed.

My great recent interruptions have (as you know) come from politics; not much in my line, you will say. But it is impossible to live here and not feel very sorely the consequences of the horrid white mismanagement. I tried standing by and looking on, and it became too much for me. They are such illogical fools; a logical fool in an office, with a lot of red tape, is conceivable. Furthermore, he is as much as we have any reason to expect of officials — a thoroughly common-place, unintellectual lot. But these people are wholly on wires; laying their ears down, skimming away, pausing as though shot, and presto! full spread on the other tack. I observe in the official class mostly an insane jealousy of the smallest kind, as compared to which the artist's is of a grave, modest character — the actor's, even; a desire to extend his little authority, and to relish it like a glass of wine, that is IMPAYABLE. Sometimes, when I see one of these little kings strutting over one of his victories — wholly illegal, perhaps, and certain to be reversed to his shame if his superiors ever heard of it — I could weep. The strange thing is that they HAVE NOTHING ELSE. I auscultate them in vain; no real sense of duty, no real comprehension, no real attempt to comprehend, no wish for information — you cannot offend one of them more bitterly than by offering information, though it is certain that you have MORE, and obvious that you have OTHER, information than they have; and talking of policy, they could not play a better stroke than by listening to you, and it need by no means influence their action. TENEZ, you know what a French post office or railway official is? That is the diplomatic card to the life. Dickens is not in it; caricature fails.

All this keeps me from my work, and gives me the unpleasant side of the world. When your letters are disbelieved it makes you angry, and that is rot; and I wish I could keep out of it with all my soul. But I have just got into it again, and farewell peace!

My work goes along but slowly. I have got to a crossing place, I suppose; the present book, SAINT IVES, is nothing; it is in no style in particular, a tissue of adventures, the central character not very well done, no philosophic pith under the yarn; and, in short, if people will read it, that's all I ask; and if they won't, damn them! I like doing it though; and if you ask me why! — after that I am on WEIR OF HERMISTON and HEATHERCAT, two Scotch stories, which will either be something different, or I shall have failed. The first is generally designed, and is a private story of two or three characters in a very grim vein. The second — alas! the thought — is an attempt at a real historical novel, to present a whole field of time; the race — our own race — the west land and Clydesdale blue bonnets, under the influence of their last trial, when they got to a pitch of organisation in madness that no other peasantry has ever made an offer at. I was going to call it THE KILLING TIME, but this man Crockett has forestalled me in that. Well, it'll be a big smash if I fail in it; but a gallant attempt. All my weary reading as a boy, which you remember well enough, will come to bear on it; and if my mind will keep up to the point it was in a while back, perhaps I can pull it through.

For two months past, Fanny, Belle, Austin (her child), and I have been alone; but yesterday, as I mentioned, Graham Balfour arrived, and on Wednesday my mother and Lloyd will make up the party to its full strength. I wish you could drop in for a month or a week, or two hours. That is my chief want. On the whole, it is an unexpectedly pleasant corner I have dropped into for an end of it, which I could scarcely have foreseen from Wilson's shop, or the Princes Street Gardens, or the Portobello Road. Still, I would like to hear what my ALTER EGO thought of it; and I would sometimes like to have my old MAITRE ES ARTS express an opinion on what I do. I put this very tamely, being on the whole a quiet elderly man; but it is a strong passion with me, though intermittent. Now, try to follow my example and tell me something about yourself, Louisa, the Bab, and your work; and kindly send me some specimens of what you're about. I have only seen one thing by you, about Notre Dame in the WESTMINSTER or ST. JAMES'S, since I left England, now I suppose six years ago.

I have looked this trash over, and it is not at all the letter I wanted to write — not truck about officials, ancestors, and the like rancidness — but you have to let your pen go in its own broken-down gait, like an old butcher's pony, stop when it pleases, and go on again as it will. — Ever, my dear Bob, your affectionate cousin,

R. L. STEVENSON.Letter: TO HENRY JAMES

VAILIMA, JULY 7TH, 1894DEAR HENRY JAMES, — I am going to try and dictate to you a letter or a note, and begin the same without any spark of hope, my mind being entirely in abeyance. This malady is very bitter on the literary man. I have had it now coming on for a month, and it seems to get worse instead of better. If it should prove to be softening of the brain, a melancholy interest will attach to the present document. I heard a great deal about you from my mother and Graham Balfour; the latter declares that you could take a First in any Samoan subject. If that be so, I should like to hear you on the theory of the constitution. Also to consult you on the force of the particles O LO 'O and UA, which are the subject of a dispute among local pundits. You might, if you ever answer this, give me your opinion on the origin of the Samoan race, just to complete the favour.

They both say that you are looking well, and I suppose I may conclude from that that you are feeling passably. I wish I was. Do not suppose from this that I am ill in body; it is the numskull that I complain of. And when that is wrong, as you must be very keenly aware, you begin every day with a smarting disappointment, which is not good for the temper. I am in one of the humours when a man wonders how any one can be such an ass as to embrace the profession of letters, and not get apprenticed to a barber or keep a baked-potato stall. But I have no doubt in the course of a week, or perhaps to-morrow, things will look better.

We have at present in port the model warship of Great Britain. She is called the CURACOA, and has the nicest set of officers and men conceivable. They, the officers, are all very intimate with us, and the front verandah is known as the Curacoa Club, and the road up to Vailima is known as the Curacoa Track. It was rather a surprise to me; many naval officers have I known, and somehow had not learned to think entirely well of them, and perhaps sometimes ask myself a little uneasily how that kind of men could do great actions? and behold! the answer comes to me, and I see a ship that I would guarantee to go anywhere it was possible for men to go, and accomplish anything it was permitted man to attempt. I had a cruise on board of her not long ago to Manu'a, and was delighted. The goodwill of all on board; the grim playfulness of — quarters, with the wounded falling down at the word; the ambulances hastening up and carrying them away; the Captain suddenly crying, 'Fire in the ward-room!' and the squad hastening forward with the hose; and, last and most curious spectacle of all, all the men in their dust- coloured fatigue clothes, at a note of the bugle, falling simultaneously flat on deck, and the ship proceeding with its prostrate crew — QUASI to ram an enemy; our dinner at night in a wild open anchorage, the ship rolling almost to her gunwales, and showing us alternately her bulwarks up in the sky, and then the wild broken cliffy palm-crested shores of the island with the surf thundering and leaping close aboard. We had the ward-room mess on deck, lit by pink wax tapers, everybody, of course, in uniform but myself, and the first lieutenant (who is a rheumaticky body) wrapped in a boat cloak. Gradually the sunset faded out, the island disappeared from the eye, though it remained menacingly present to the ear with the voice of the surf; and then the captain turned on the searchlight and gave us the coast, the beach, the trees, the native houses, and the cliffs by glimpses of daylight, a kind of deliberate lightning. About which time, I suppose, we must have come as far as the dessert, and were probably drinking our first glass of port to Her Majesty. We stayed two days at the island, and had, in addition, a very picturesque snapshot at the native life. The three islands of Manu'a are independent, and are ruled over by a little slip of a half-caste girl about twenty, who sits all day in a pink gown, in a little white European house with about a quarter of an acre of roses in front of it, looking at the palm-trees on the village street, and listening to the surf. This, so far as I could discover, was all she had to do. 'This is a very dull place,' she said. It appears she could go to no other village for fear of raising the jealousy of her own people in the capital. And as for going about 'tafatafaoing,' as we say here, its cost was too enormous. A strong able-bodied native must walk in front of her and blow the conch shell continuously from the moment she leaves one house until the moment she enters another. Did you ever blow the conch shell? I presume not; but the sweat literally hailed off that man, and I expected every moment to see him burst a blood-vessel. We were entertained to kava in the guest-house with some very original features. The young men who run for the KAVA have a right to misconduct themselves AD LIBITUM on the way back; and though they were told to restrain themselves on the occasion of our visit, there was a strange hurly-burly at their return, when they came beating the trees and the posts of the houses, leaping, shouting, and yelling like Bacchants.

I tasted on that occasion what it is to be great. My name was called next after the captain's, and several chiefs (a thing quite new to me, and not at all Samoan practice) drank to me by name.

And now, if you are not sick of the CURACOA and Manu'a, I am, at least on paper. And I decline any longer to give you examples of how not to write.

By the by, you sent me long ago a work by Anatole France, which I confess I did not TASTE. Since then I have made the acquaintance of the ABBE COIGNARD, and have become a faithful adorer. I don't think a better book was ever written.

And I have no idea what I have said, and I have no idea what I ought to have said, and I am a total ass, but my heart is in the right place, and I am, my dear Henry James, yours,

R. L. S.Letter: TO MR. MARCEL SCHWOB

VAILIMA, UPOLU, SAMOA, JULY 7, 1894DEAR MR. MARCEL SCHWOB, — Thank you for having remembered me in my exile. I have read MIMES twice as a whole; and now, as I write, I am reading it again as it were by accident, and a piece at a time, my eye catching a word and travelling obediently on through the whole number. It is a graceful book, essentially graceful, with its haunting agreeable melancholy, its pleasing savour of antiquity. At the same time, by its merits, it shows itself rather as the promise of something else to come than a thing final in itself. You have yet to give us — and I am expecting it with impatience — something of a larger gait; something daylit, not twilit; something with the colours of life, not the flat tints of a temple illumination; something that shall be SAID with all the clearnesses and the trivialities of speech, not SUNG like a semi- articulate lullaby. It will not please yourself as well, when you come to give it us, but it will please others better. It will be more of a whole, more worldly, more nourished, more commonplace — and not so pretty, perhaps not even so beautiful. No man knows better than I that, as we go on in life, we must part from prettiness and the graces. We but attain qualities to lose them; life is a series of farewells, even in art; even our proficiencies are deciduous and evanescent. So here with these exquisite pieces the XVIIth, XVIIIth, and IVth of the present collection. You will perhaps never excel them; I should think the 'Hermes,' never. Well, you will do something else, and of that I am in expectation. — Yours cordially,

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON.Letter: TO A. ST. GAUDENS

VAILIMA, SAMOA, JULY 8, 1894MY DEAR ST. GAUDENS, — This is to tell you that the medallion has been at last triumphantly transported up the hill and placed over my smoking-room mantelpiece. It is considered by everybody a first-rate but flattering portrait. We have it in a very good light, which brings out the artistic merits of the god-like sculptor to great advantage. As for my own opinion, I believe it to be a speaking likeness, and not flattered at all; possibly a little the reverse. The verses (curse the rhyme) look remarkably well.

Please do not longer delay, but send me an account for the expense of the gilt letters. I was sorry indeed that they proved beyond the means of a small farmer. — Yours very sincerely,

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON.Letter: TO MISS ADELAIDE BOODLE

VAILIMA, JULY 14, 1894MY DEAR ADELAIDE, — .. So, at last, you are going into mission work? where I think your heart always was. You will like it in a way, but remember it is dreary long. Do you know the story of the American tramp who was offered meals and a day's wage to chop with the back of an axe on a fallen trunk. 'Damned if I can go on chopping when I can't see the chips fly!' You will never see the chips fly in mission work, never; and be sure you know it beforehand. The work is one long dull disappointment, varied by acute revulsions; and those who are by nature courageous and cheerful and have grown old in experience, learn to rub their hands over infinitesimal successes. However, as I really believe there is some good done in the long run — GUTTA CAVAT LAPIDEM NON VI in this business — it is a useful and honourable career in which no one should be ashamed to embark. Always remember the fable of the sun, the storm, and the traveller's cloak. Forget wholly and for ever all small pruderies, and remember that YOU CANNOT CHANGE ANCESTRAL FEELINGS OF RIGHT AND WRONG WITHOUT WHAT IS PRACTICALLY SOUL-MURDER. Barbarous as the customs may seem, always hear them with patience, always judge them with gentleness, always find in them some seed of good; see that you always develop them; remember that all you can do is to civilise the man in the line of his own civilisation, such as it is. And never expect, never believe in, thaumaturgic conversions. They may do very well for St. Paul; in the case of an Andaman islander they mean less than nothing. In fact, what you have to do is to teach the parents in the interests of their great-grandchildren.

Now, my dear Adelaide, dismiss from your mind the least idea of fault upon your side; nothing is further from the fact. I cannot forgive you, for I do not know your fault. My own is plain enough, and the name of it is cold-hearted neglect; and you may busy yourself more usefully in trying to forgive me. But ugly as my fault is, you must not suppose it to mean more than it does; it does not mean that we have at all forgotten you, that we have become at all indifferent to the thought of you. See, in my life of Jenkin, a remark of his, very well expressed, on the friendships of men who do not write to each other. I can honestly say that I have not changed to you in any way; though I have behaved thus ill, thus cruelly. Evil is done by want of — well, principally by want of industry. You can imagine what I would say (in a novel) of any one who had behaved as I have done, DETERIORA SEQUOR. And you must somehow manage to forgive your old friend; and if you will be so very good, continue to give us news of you, and let us share the knowledge of your adventures, sure that it will be always followed with interest — even if it is answered with the silence of ingratitude. For I am not a fool; I know my faults, I know they are ineluctable, I know they are growing on me. I know I may offend again, and I warn you of it. But the next time I offend, tell me so plainly and frankly like a lady, and don't lacerate my heart and bludgeon my vanity with imaginary faults of your own and purely gratuitous penitence. I might suspect you of irony!

We are all fairly well, though I have been off work and off — as you know very well — letter-writing. Yet I have sometimes more than twenty letters, and sometimes more than thirty, going out each mail. And Fanny has had a most distressing bronchitis for some time, which she is only now beginning to get over. I have just been to see her; she is lying — though she had breakfast an hour ago, about seven — in her big cool, mosquito-proof room, ingloriously asleep. As for me, you see that a doom has come upon me: I cannot make marks with a pen — witness 'ingloriously' above; and my amanuensis not appearing so early in the day, for she is then immersed in household affairs, and I can hear her 'steering the boys' up and down the verandahs — you must decipher this unhappy letter for yourself and, I fully admit, with everything against you. A letter should be always well written; how much more a letter of apology! Legibility is the politeness of men of letters, as punctuality of kings and beggars. By the punctuality of my replies, and the beauty of my hand-writing, judge what a fine conscience I must have!

Now, my dear gamekeeper, I must really draw to a close. For I have much else to write before the mail goes out three days hence. Fanny being asleep, it would not be conscientious to invent a message from her, so you must just imagine her sentiments. I find I have not the heart to speak of your recent loss. You remember perhaps, when my father died, you told me those ugly images of sickness, decline, and impaired reason, which then haunted me day and night, would pass away and be succeeded by things more happily characteristic. I have found it so. He now haunts me, strangely enough, in two guises; as a man of fifty, lying on a hillside and carving mottoes on a stick, strong and well; and as a younger man, running down the sands into the sea near North Berwick, myself — AETAT. II — somewhat horrified at finding him so beautiful when stripped! I hand on your own advice to you in case you have forgotten it, as I know one is apt to do in seasons of bereavement. — Ever yours, with much love and sympathy,