Полная версия:

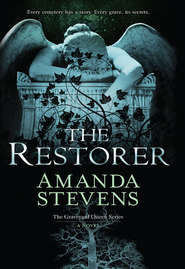

The Restorer

Praise for the novels of

AMANDA STEVENS

“Stevens makes her MIRA debut with this taut, disturbing story.

The characterizations are vivid, and it’s got a lovely twist

in the tail. Not for the squeamish!”

—RT Book Reviews on The Dollmaker

“Fast paced and plotted with spectacular precision and guile,

this is undiluted suspense at its very finest.

Nervous readers should read it in full daylight.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Devil’s Footprints

“Stevens’ swiftly-moving, intricately plotted story

has oodles of twists and chills—plus a jaw-dropping shocker

of an ending. This is good stuff indeed.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Whispering Room

The Restorer

Amanda Stevens

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Epilogue

ONE

I was nine when I saw my first ghost.

My father and I were raking leaves in the cemetery where he’d worked for years as the caretaker. It was early autumn, not yet cool enough for a sweater, but on that particular afternoon there was a noticeable bite in the air as the sun dipped toward the horizon. A mild breeze carried the scent of wood smoke and pine needles, and as the wind picked up, a flock of black birds took flight from the treetops and glided like a storm cloud across the pale blue sky.

I put a hand to my eyes as I watched them. When my gaze finally dropped, I saw him in the distance. He stood beneath the drooping branches of a live oak, and the green-gold light that glimmered down through the Spanish moss cast a preternatural glow on the space around him. But he was in shadows, so much so that I wondered for a moment if he was only a mirage.

As the light faded, he became more defined, and I could even make out his features. He was old, even more ancient than my father, with white hair brushing the collar of his suit coat and eyes that seemed to burn with an inner flame.

My father was bent to his work and as the rake moved steadily over the graves, he said under his breath, “Don’t look at him.”

I turned in surprise. “You see him, too?”

“Yes, I see him. Now get back to work.”

“But who is he—”

“I said don’t look at him!”

His sharp tone stunned me. I could count on one hand the number of times he’d ever raised his voice to me. That he had done so now, without provocation, made me instantly tear up. The one thing I could never abide was my father’s disapproval.

“Amelia.”

There was regret in his tone and what I would later come to understand as pity in his blue eyes.

“I’m sorry I spoke so harshly, but it’s important that you do as I say. You mustn’t look at him,” he said in a softer tone. “Any of them.”

“Is he a—”

“Yes.”

Something cold touched my spine and it was all I could do to keep my gaze trained on the ground.

“Papa,” I whispered. I had always called him this. I don’t know why I’d latched onto such an old-fashioned moniker, but it suited him. He had always seemed very old to me, even though he was not yet fifty. For as long as I could remember, his face had been heavily lined and weathered, like the cracked mud of a dry creek bed, and his shoulders drooped from years of bending over the graves.

But despite his poor posture, there was great dignity in his bearing and much kindness in his eyes and in his smile. I loved him with every fiber of my nine-year-old being. He and Mama were my whole world. Or had been, until that moment.

I saw something shift in Papa’s face and then his eyes slowly closed in resignation. He laid aside our rakes and placed his hand on my shoulder.

“Let’s rest for a spell,” he said.

We sat on the ground, our backs to the ghost, as we watched dusk creep in from the Lowcountry. I couldn’t stop shivering, even though the waning light was still warm on my face.

“Who is he?” I finally whispered, unable to bear the quiet any longer.

“I don’t know.”

“Why can’t I look at him?” It occurred to me then that I was more afraid of what Papa was about to tell me than I was of the ghost.

“You don’t want him to know that you can see him.”

“Why not?” When he didn’t answer, I picked up a twig and poked it through a dead leaf, spinning it like a pinwheel between my fingers. “Why not, Papa?”

“Because what the dead want more than anything is to be a part of our world again. They’re like parasites, drawn to our energy, feeding off our warmth. If they know you can see them, they’ll cling to you like blight. You’ll never be rid of them. And your life will never again be your own.”

I don’t know if I completely understood what he told me, but the notion of being haunted forever terrified me.

“Not everyone can see them,” he said. “For those of us who can, there are certain precautions we must take in order to protect ourselves and those around us. The first and most important is this—never acknowledge the dead. Don’t look at them, don’t speak to them, don’t let them sense your fear. Even when they touch you.”

A chill shimmied over me. “They…touch you?”

“Sometimes they do.”

“And you can feel it?”

He drew a breath. “Yes. You can feel it.”

I threw away the stick, and pulled up my knees, wrapping my arms tightly around them. Somehow, even at my young age, I was able to remain calm on the outside, but my insides had gone numb with dread.

“The second thing you must remember is this,” Papa said. “Never stray too far from hallowed ground.”

“What’s hallowed ground?”

“The old part of this cemetery is hallowed ground. There are other places, too, where you’ll be safe. Natural places. After a while, instinct will lead you to them. You’ll know where and when to seek them out.”

I tried to digest this puzzling detail, but I really didn’t understand the concept of hallowed ground, although I’d always known the old part of the cemetery was special.

Nestled against the side of a hill and protected by the outstretched arms of the live oaks, Rosehill was shady and beautiful, the most serene place I could imagine. It had been closed to the public for years, and sometimes as I wandered alone—and often lonely—through the lush fern beds and long curtains of silvery moss, I pretended the crumbling angels were wood nymphs and fairies and I their ruler, queen of my very own graveyard kingdom.

My father’s voice brought me back to the real world. “Rule Number Three,” he said. “Keep your distance from those who are haunted. If they seek you out, turn away from them, for they constitute a terrible threat and cannot be trusted.”

“Are there any more rules?” I asked, because I didn’t know what else I was supposed to say.

“Yes, but we’ll talk about the rest later. It’s getting late. We should probably head home before your mother starts to worry.”

“Can she see them?”

“No. And you mustn’t tell her that you can.”

“Why not?”

“She doesn’t believe in ghosts. She’d think you’re imagining things. Or telling stories.”

“I would never lie to Mama!”

“I know that. But this has to be our secret. When you’re older, you’ll understand. For now, just do your best to follow the rules and everything will be fine. Can you do that?”

“Yes, Papa.” But even as I promised, it was all I could do to keep from glancing over my shoulder.

The breeze picked up and the chill inside me deepened. Somehow, I managed to keep from turning, but I knew the ghost had drifted closer. Papa knew it, too. I could feel the tension in him as he murmured, “No more talking. Just remember what I told you.”

“I will, Papa.”

The ghost’s frigid breath feathered down the back of my neck and I started to tremble. I couldn’t help myself.

“Cold?” my father asked in his normal voice. “Well, it’s getting to be that time of year. Summer can’t last forever.”

I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t. The ghost’s hands were in my hair. He lifted the golden strands, still warm from the sun, and let them sift through his fingers.

Papa got to his feet and pulled me up with him. The ghost skittered away for a moment, then floated back.

“We best be getting on home. Your mother’s cooking up a mess of shrimp tonight.” He picked up the rakes and hoisted them to his shoulder.

“And grits?” I asked, though my voice was hardly louder than a whisper.

“I expect so. Come on. Let’s cut through the old cemetery. I want to show you the work I’ve done on some of the gravestones. I know how much you love the angels.”

He took my hand and squeezed my fingers in reassurance as we set out across the cemetery, the ghost at our heels.

By the time we reached the old section, Papa had already pulled the key from his pocket. He turned the lock and the heavy iron gate swung silently inward on well-oiled hinges.

We stepped through into that dusky sanctuary and suddenly I wasn’t afraid anymore. My newfound courage emboldened me. I pretended to trip and when I bent to tie my shoelaces, I glanced back at the gate. The ghost hovered just outside. It was obvious he was unable to enter, and I couldn’t help but give a childish smirk.

When I straightened, Papa glared down at me. “Rule Number Four,” he said sternly. “Never, ever tempt fate.”

The childhood memory flitted away as the waitress approached with my first course—roasted green-tomato soup, which I’d been told was a house specialty—along with the pecan pie I planned to have for desert. Six months ago, I’d moved from Columbia to Charleston, making it my home base, but I’d never had dinner at any of the upscale waterfront restaurants. My budget normally didn’t allow for fine dining, but tonight was special.

As the waitress topped off my champagne, I caught her curious, sidelong glance, but I didn’t let it bother me. Just because I happened to be alone was no reason to deprive myself of a celebration.

Earlier, I’d taken a leisurely stroll along the Battery, pausing at the very tip of the peninsula to enjoy the sunset. Behind me, the whole city was bathed in crimson; before me, a fractured sky shifted into kaleidoscopic patterns of rose, lavender and gold. A Carolina sunset never failed to move me, but with the approaching twilight everything had turned gray. Mist drifted in from the sea and settled over the treetops like a silver canopy. As I watched the gauzy swirl from a table by the window, my elation faded.

Dusk is a dangerous time for people like me. An in-between time just as the seashore and the edge of a forest are in-between places. The Celts had a name for these landscapes—caol’ ait. Thin places where the barrier between our world and the next is but a gossamer veil.

Turning from the window, I sipped champagne, determined not to let the encroaching spirit world spoil my celebration. After all, it wasn’t every day an unexpected windfall came my way, and for barely lifting a finger.

My work usually consists of many hours of manual labor for modest pay. I’m a cemetery restorer. I travel all over the South, cleaning up forgotten and abandoned graveyards and repairing worn and broken headstones. It’s painstaking, sometimes back-breaking work, and a huge cemetery can take years to restore fully, so there is no such thing as instant gratification in my profession. But I love what I do. We Southerners worship our ancestors, and I’m gratified that my efforts in some small way enable people of the present to more fully appreciate those who came before us.

In my spare time, I run a blog called Digging Graves, where taphophiles—lovers of cemeteries—and other like-minded folks can exchange photographs, restoration techniques and, yes, even the occasional ghost story. I’d started the blog as a hobby, but over the past few months, my readership had exploded.

It all started with the restoration of an old cemetery in the small, northeast Georgia town of Samara. The freshest grave there was over a hundred years old and some of the earliest dated back to pre–Civil War days.

The cemetery had been badly neglected since the local historical society ran out of money in the sixties. The sunken graves were overgrown, the headstones worn nearly smooth by erosion. Vandals had been busy there, too, and the first order of business was to pick up and cart away nearly four decades of trash.

Rumors of a haunting had persisted for years and some of the townspeople refused to set foot through the gates. It was hard to find and keep good help, even though I knew for a fact there were no ghosts in Samara Cemetery.

I ended up doing most of the work myself, but once the cleanup was completed, the attitude of the locals transformed dramatically. They said it was as if a dark cloud had been lifted from their town, and some went so far as to claim that the restoration had been both physical and spiritual.

A reporter and film crew from a station in Athens were sent out to interview me and when the clip turned up online, someone noticed a reflection in the background that had a vague, humanlike form. It appeared to be floating over the cemetery, ascending heavenward.

There was nothing supernatural about the anomaly, merely a trick of the light, but dozens of paranormal websites ran with it and the YouTube video went viral. That’s when people from all over the world started flocking to Digging Graves, where I was known as the Graveyard Queen. The traffic became so heavy that the producers of a ghost hunter television program made an offer to advertise on my site.

Which is how I came to be sipping champagne and savoring a wild mushroom tart at the glamorous Pavilion on the Bay restaurant.

Life was treating me well these days, I thought a little smugly, and then I saw the ghost.

Even worse, he saw me.

TWO

I don’t often recognize the faces of the entities I encounter, but at times I have experienced a prickle of déjà vu, as if I might have glimpsed them in passing. I’m fortunate that in all my twenty-seven years, I’ve never lost anyone truly close to me. I do remember an encounter back in high school with the ghost of a teacher, though. Her name was Miss Compton and she’d been killed in a car crash over a holiday long weekend. When classes resumed the following Tuesday, I’d stayed late to work on a project and I saw her spirit hovering in the dusky hallway near my locker. The manifestation had caught me off guard because in life, Miss Compton had been so demure and unassuming. I hadn’t expected her to come back grasping and greedy, hungrily seeking what she could never have again.

Somehow I managed to keep my poise as I grabbed my backpack and closed my locker. She trailed me down the long hallway and through the front door, her chill breath on my neck, her icy hands clutching at my clothes. It was a long time before the air around me warmed and I knew she’d dissolved back into the netherworld. After that I made sure I was safely away from school before twilight, which meant no extracurricular activities. No ball games, no parties, no prom. I couldn’t take the chance of running into Miss Compton again. I was too afraid she might somehow latch onto me and then my life would never again be my own.

I turned my attention back to the ghost in the restaurant. I recognized him, too, but I didn’t know him personally. I’d seen his picture on the front page of the Post and Courier a few weeks ago. His name was Lincoln McCoy, a prominent Charleston businessman who’d slaughtered his wife and children one night and then shot himself in the head rather than surrender to the S.W.A.T. team that had surrounded his house.

The way he appeared to me now was quite ethereal, with no evidence of the wrongs he’d committed on himself or his family. Except for his eyes. They were dark and blazing, yet at the same time icy. As he peered at me across the restaurant, I saw a faint smile touch his ghostly features.

Instead of flinching or glancing away in fright, I stared right back at him. He’d drifted into the restaurant behind an elderly couple who were now waiting to be seated. As his eyes held mine, I pretended to look right through him, even going so far as to wave at an imaginary acquaintance.

The ghost glanced over his shoulder, and at that precise moment, a waitress saw my wave and lifted one finger, indicating she would be with me in a moment. I nodded, smiled and picked up my champagne glass as I turned back to the window. I didn’t look at the ghost again, but I felt his frigid presence a moment later as he glided past my table, still trailing the old couple.

I wondered why he had attached himself to that particular pair and if on some level they were aware of his presence. I wanted to warn them, but I couldn’t without giving myself away. And that was what he wanted. What he desperately craved. To be acknowledged by the living so that he could feel a part of our world again.

Hands steady, I paid my check and left the restaurant without looking back.

Once outside, I allowed myself to relax as I walked back along White Point Gardens, in no particular hurry to seek the sanctuary of my home. Whatever spirits had managed to slip through the veil at dusk were already among us and as long as I remained vigilant until the sun came up, I needn’t cower from the icy drafts and swirling gray forms.

The mist had thickened. The Civil War cannons and statues in the park were invisible from the walkway, the bandstand and live oaks nothing more than vague silhouettes. But I could smell the flowers, that luscious blend of what I had come to think of as the Charleston scent—magnolia, hyacinth and Confederate jasmine.

Somewhere in the darkness, a foghorn sounded and out in the harbor, a lighthouse flashed warnings to the cargo ships traversing the narrow channel between Sullivan’s Island and Fort Sumter. As I stopped to watch the light, an uneasy chill crept over me. Someone was behind me in the fog. I could hear the soft yet unmistakable clop of leather soles against the seawall.

The footfalls stopped suddenly and I turned with a breathless shiver. For a long moment, nothing happened and I began to think I might have imagined the sound. Then he emerged from the veil of mist, sending the blood out of my heart with a painful contraction.

Tall, broad-shouldered and dressed all in black, he might have stepped from the dreamy hinterland of some childhood fable. I could barely make out his features, but I knew instinctively that he was handsome and brooding. The way he carried himself, the almost painful glare of his eyes through the mist, sent icy needles stinging down my spine.

He was no ghost, but dangerous to me nonetheless and so compelling I couldn’t tear my gaze away as he moved toward me. And now I could see water droplets glistening in his dark hair and the gleam of a silver chain tucked inside the collar of his dark shirt.

Behind him, translucent and hardly discernible from the mist, were two ghosts, that of a woman and a little girl. They were both looking at me, too, but I kept my gaze trained on the man.

“Amelia Gray?”

“Yes?” Since my blog had become so popular, I was occasionally approached by strangers who recognized me from website photos or from the infamous ghost video. The South, particularly the Charleston area, was home to dozens of avid taphophiles, but I didn’t think this man was a fan or a fellow aficionado. His eyes were cold, his manner aloof. He had not sought me out to chitchat about headstones.

“I’m John Devlin, Charleston PD.” As he spoke, he hauled out his wallet and presented his ID and badge, which I obligingly glanced at even though my heart had started to beat an agonizing staccato.

A police detective!

This couldn’t be good.

Something terrible must have happened. My parents were getting on in years. What if one of them had had an accident or taken ill or…

Tamping down an unreasonable panic, I slipped my hands into the pockets of my trench coat. If something had happened to Mama or Papa, someone would have called. This wasn’t about them. This was about me.

I waited for an explanation as those lovely apparitions hovered protectively around John Devlin. From what I could see of the woman’s features, she’d been stunning, with high cheekbones and proudly flaring nostrils that suggested a Creole heritage. She wore a pretty summer dress that swirled like gossamer around her long, slender legs.

The child looked to have been four or five when she died. Dark curls framed her pale face as she floated at the man’s side, reaching out now and then to clutch at his leg or tap on his knee.

He seemed oblivious to their presence, though he was clearly haunted. It showed in his face, in the eyes that were as hooded as they were piercing, and I couldn’t help wondering about his relationship to the ghosts.

I kept my eyes focused on his face. He was watching me, too, with an air of suspicion and superiority that could make dealing with the police an unpleasant ordeal, even over something as trivial as a parking ticket.

“What do you want?” I asked, though I hadn’t meant for the query to sound so blunt. I’m not a confrontational person. Years of living with ghosts had whittled away my spontaneity, leaving me overly disciplined and reserved.

Devlin moved a step closer and my hands curled into fists inside my coat pockets. A thrill chased across my skull and I wanted to tell him to keep his distance, don’t come any closer. I said nothing, of course, as I braced myself against the frigid breath of his phantoms.

“A mutual acquaintance suggested I get in touch with you,” he said.

“And who would that be?”

“Camille Ashby. She thought you might be able to help me out.”

“With what?”

“A police matter.”

Now I was more curious than cautious—which made me also foolish.

Dr. Camille Ashby was an administrator at Emerson University, an elite, private college with powerful alumni that included some of the most prominent lawyers, judges and businessmen in South Carolina. Recently, I’d accepted a commission to restore an old cemetery located on university property. One of Dr. Ashby’s stipulations was that I not post any pictures on my blog until the restoration was complete.

I understood her concern. The dismal condition of the graveyard wasn’t a favorable reflection on a university that espoused the traditions and ethics of the old South. As Benjamin Franklin had put it: One can tell the morals of a culture by the way they treat their dead. Indeed.

What I didn’t yet know was why she’d sent John Devlin to find me.