Полная версия:

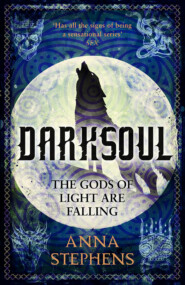

Darksoul

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Anna Smith 2018

Map copyright © Sophie E. Tallis 2017

Cover design by Dominic Forbes © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

Anna Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008215941

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008215965

Version: 2018-07-12

Dedication

For Mum, Dad, and Sam.

Thanks for letting me grow up weird.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Durdil

Galtas

The Blessed One

Durdil

Galtas

Gilda

Dom

Durdil

Corvus

Mace

Durdil

Corvus

Tara

Gilda

Crys

Rillirin

Mace

Rillirin

Galtas

Crys

Galtas

The Blessed One

Durdil

Crys

Durdil

Corvus

Tara

Crys

Mace

Rillirin

Corvus

Dom

Crys

The Blessed One

Tara

Corvus

Tara

Galtas

Corvus

Mace

Crys

Tara

Crys

Dom

The Blessed One

Dom

Crys

Rillirin

Corvus

Mace

Dom

Tara

Mace

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

By Anna Stephens

About the Publisher

DURDIL

Fourth moon, morning, day seventeen of the siege

King’s chamber, the palace, Rilporin, Wheat Lands

The last length of yellowed, crusted bandage came away with a soft sucking sound, and the sickly-sweet, hideous scent of rot plumed into the air. Hallos’s nose wrinkled; Durdil coughed hard and then snorted. It didn’t clear the stink. On the opposite side of the bed, two of the priests faltered in their chanting, and then, halting, retching, caught up with the others.

Durdil peered over Hallos’s shoulder. ‘How …’

‘How is he still alive? Gods only know,’ Hallos grunted. He used a long silver spoon with a slim bowl to poke at the wound and Durdil was reminded, sickeningly, of eating a custard tart. He swallowed, tasting bile. ‘The end’s near though, Durdil. Very near.’

‘And the enemy is clamouring at our gates,’ Durdil fretted. ‘I need to be on the wall. But … what if he wakes?’

Hallos jabbed the spoon against the neatly sutured, red and yellow, weeping flesh of Rastoth’s chest. The dying man moaned but did not stir. ‘He’s not waking up again, my friend,’ he said softly. ‘Not this side of the Light.’

He straightened and faced Durdil, and Durdil gritted his teeth against what he knew was coming. Again. ‘He may be unconscious, but he’s in unspeakable agony in there nonetheless. It’s time we eased his pain.’

‘He’s the king, Hallos. Ending his life would be regicide,’ Durdil said, weariness taking the fervour from his words so they just came out defeated instead. The voice in the back of his head agreed with the physician, pointed out that if it was him, he’d be begging them to do it. He pushed it away and looked to the priests for aid, but the most senior, Erik, gave a slow nod of agreement even as he prayed. No help there.

Hallos’s black eyebrows, flecked with grey these days, drew down and he touched Durdil’s arm. ‘It would be a mercy, Durdil. A mercy for your friend.’ Durdil opened his mouth but Hallos held up a finger. ‘Would you deny a soldier – an officer, even a prince – the grace on the field of battle? No. You’d end their agony and pray them into the Dancer’s embrace. Rastoth was a soldier, campaigned for years to the south and the east. Fought the Krikites, fought the Listrans. Treat him as a soldier one last time. Do him that honour and let us gift him into the Light.’

At his words the priests shifted their chanting and Durdil recognised the song of mourning and of celebration of a life well lived. They were singing as though he was already dead and Durdil’s last choice was taken from him.

His heart was breaking, had been breaking every hour of this endless, desperate siege. He was too tired to think clearly, too exhausted in body and mind to make any decision not immediately related to the preservation of the city for one more day. He had no idea what to do, why this decision had to fall to him. I’m the Commander of the Ranks, not the arbiter of life and death for kings. Not my king, anyway. Not Rastoth.

The king’s face was ashen, except for the hectic spots of red caused by the fever. Black lines ran from the neat tear in his chest and the lips of the wound were red, angry, puckered, straining at their stitches as they swelled. Monstrous and on the point of bursting. Obscene, over-ripe fruit that wanted only a touch, a breath, to split and spill its horror.

Durdil had chewed his lip to ribbons since the siege began and winced as he bit at it now. He scrubbed a hand across the back of his head and down his neck. Erik nodded again when he looked to him for aid. Hallos was waiting, the plea clear on his lips and in his eyes. Give him what he can’t ask for himself. Help him, as you’ve helped him all your life. Serve him.

‘I’ll tell the council he succumbed to his wound,’ Durdil said eventually. ‘They know it’s inevitable, so we’ll let them think it was a natural end. Otherwise, our noble Lords Lorca and Silais are likely stupid enough to accuse us of treason in the midst of this … mess.’

Each of the priests nodded and their voices swelled louder, urging Rastoth’s spirit to begin breaking its anchors to his dying, rotting flesh.

‘Opium?’ Hallos murmured, selecting a small jar with a hand that didn’t – and Durdil felt should – shake.

‘You’ll never get him to swallow it. Will you?’

Hallos’s smile was weary and sad. ‘There are things you will never know of my art, my old friend. Don’t worry. Just … say your goodbyes, yes? We should do it quickly, now the decision has been made. We should spare him any more of this … this sham of life.’

Hallos stepped out of his way and Durdil looked again at his king, his decades-long friend, lying still and pale against the pillows. Rastoth’s breath came in tiny pants, clammy sweat glistening in the gloom. His hands were claws. From the open window came the sound of a dog-boy playing with a litter of puppies, uncaring of the dying king or besieged city.

Durdil fell to one knee by the bed, his armour clattering about his shoulders. ‘Sire, forgive me,’ he whispered, ‘I should have protected you, kept you safe …’ The man might be old and mad, but he was Durdil’s king and Durdil’s friend.

‘I will save Rilporin, Rastoth. I will save our country and our gods, our people. All of it. I swear on my hope of reaching the Light. When we meet again, I …’ He choked back a sob.

Hallos squeezed past him and an involuntary denial sprang to Durdil’s lips, a hand reaching to stop the cup on its way to Rastoth’s lips.

Erik rounded the bed and pulled him gently to his feet. ‘Your last act for your king, Commander, should be the one that brings him peace,’ he murmured. ‘Don’t interfere now. Pray.’

Durdil’s lips began moving in prayer as the priests sang, as Hallos raised Rastoth’s head with pillows and tipped small, patient sips of wine and opium into his mouth, massaging his throat until he swallowed. Rastoth’s breathing slowed as the drug stole his pain, as it relaxed his limbs, as it took his mind far, far away from the ruin of his body and the ashes of his reign.

Durdil crowded close, found Rastoth’s leg beneath the covers and rested his hand there. ‘Marisa’s waiting,’ he said hoarsely. ‘Marisa and Janis both. In the Light. Waiting for you. Tell her I said hello and … and ask her to forgive me. I failed you, all three of you. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.’

Something that might have been a smile, or just the last twitch of dying muscles, crossed his face, and then Rastoth the Kind, Rastoth the Mad, exhaled a last, bubbling breath and died.

Durdil stared in silence at the council gathered in the war room, his fingers steepled before his lips. His eyes were red with fatigue and grief, and he’d delivered the news of Rastoth’s death into a silence that was thick with alliances and churning with calculation. As expected, both Lords Lorca and Silais were clearly vying to win the majority of the council and be the next power in Rilporin. Perhaps even to sit on the throne.

‘My lords, as grievous as this news is, I will not be releasing it to the populace or the Rank. Nor will we be flying the scarlet or declaring a week of official mourning, as is customary. We are at war, my lords, and as of now martial law is in effect. Those of us who live to see the siege’s conclusion can carry out the funeral rites with all pomp and ceremony at that point. For now, we concern ourselves only with the fight.’

‘This is preposterous; you have not the authority,’ Lord Lorca began, his silver tongue momentarily losing its sheen. ‘King Rastoth must be—’

‘King Rastoth is dead. We the living have more important things to worry about than feasting his memory or arguing about interim governments. The state of the wall, for instance. The enemy’s trebuchets have been loosing at it for days now. The Stonemasons’ Guild is inspecting it daily for weaknesses. I’ve asked them to—’

‘You do not ask the stonemasons anything,’ Silais muttered, ‘not if you want them to actually do anything. You order them. Order, I say.’

‘Thank you for your opinion, Lord Silais, but they’re working ceaselessly and providing regular reports,’ Durdil said. ‘There is little more I, or they, can do than that. I have also spoken with the pigeon-master, and it appears that while he was in the city, Prince Rivil—’

‘King Rivil, surely,’ a voice said. Durdil glanced at Questrel Chamberlain. The man simpered and smoothed down his oiled hair. ‘By right and blood, my lords, Commander, the prince is now our king. Surely we should address him as such.’

A babble rose among the nobles, ermine flying as they gesticulated, the volume increasing, the tone becoming angry, strident. Durdil steepled his hands again and leant back in his chair, waiting, the sound of arguing noblemen washing over him.

It got louder before it got quieter, but eventually more and more councillors noticed Durdil was taking no part in the debate. They loathed him to a man, but he was Commander of the Ranks and led the defence. The decision, ultimately, was his. Either he opened the gates to Rivil, proclaiming him king … or he didn’t, proclaiming them all traitors to the throne.

A fine choice. I cannot wait to make it.

Durdil waited until there was silence, and then he waited a few moments longer until they were squirming.

‘My lords, Prince Rivil attempted regicide. Before that he was implicated in his own mother’s murder and converted to the bloodthirsty faith of our ancient enemies by way of killing his brother, the rightful heir to the throne. There is no man more unfit to rule our great country than he. As I began to say, the pigeon-master confirms that all birds trained to fly to Highcrop in Listre, the home of the only surviving – and distant – member of the line of succession, were killed by Rivil or the Lord Galtas Morellis. We cannot inform Lord Tresh that Rastoth has fallen, that Rivil is cast out of the succession. Once this siege is lifted, however, I will send an emissary to his lordship with all haste, informing him that he is now our king.’

‘Tresh? Never heard of ’im,’ a voice muttered.

‘Not even a full blood,’ another whispered. ‘More Listran than Rilporian. Listran, I ask you!’

‘Tresh is a bastard, isn’t he?’

‘King Tresh,’ Durdil snapped, his temper wearing ever thinner, ‘is by all accounts a studious man and astute judge of character. He will make a fine king, especially with a council such as this to advise him.’

To hinder him, to kiss his arse and bleed him dry and blind him to all but their wants, their needs, their desires. If only the gods would allow me to put every last bloody one of them in the catapult baskets and send them out to meet their foes.

Durdil bit down on a smile as he imagined the long, drawn-out wail of outrage Lorca would make as he flew skyward. Please, Dancer, just one.

‘Until then, my lords, we remain at war. And martial law is the order of the day.’

‘I support your proposal,’ Lorca said, though they both knew it was no such thing. ‘Take steps to curb the unruly peasantry even now hoarding food from their betters and breathe new strength into our men. A good thing, too. Some of them flag already.’

Already? They’ve been defending this city for over a fortnight. They’ve done more for Rilporin and its people in that time than you have in your entire life. They spend their lives like coppers, without thought, and they do it for the city and the king. They do it, gods love them, for me. And I have to order them to … calm, Durdil. Calm.

Durdil found that his grief and his fatigue combined to make a heady, dangerous, short-tempered brew. He raised his fist to his mouth and bit the knuckle hard, focusing on the pain as the muttering swelled anew.

‘If that is all, my lords, I have a wall to defend,’ he barked, screeching his chair back over the flagstones and cutting the conversation dead.

The council rose and paused; normally this was when they’d bow to the king. A couple dipped their heads in an awkward half-salute. Lorca’s pale eyes studied Durdil for a moment too long, and then he swept from the war room with his cronies hurrying after him.

Silais remained seated, inspecting his perfect fingernails until Lorca had cleared the doorway. It just wouldn’t do for him to be held up by the man. Durdil resisted the urge to spit on the table and stalked from the room, Hallos trailing miserably behind him and Major Vaunt bringing up the rear. In the days since the siege had begun, the hour in the war room was the only time most of his officers got away from the wall or the barracks or the hospital. Durdil had taken to rotating the privilege between them so that each of them had the excuse for a bath and a change of clothes every few days.

And aren’t they already seeing it as a luxury, he thought. How quickly the unbearable becomes normal. And now I have to tell my officers that Rastoth is dead and to keep it secret.

And there’s still no word from the North Rank. Where the bloody fuck are my reinforcements?

GALTAS

Fourth moon, morning, day twenty-two of the siege

East Rank encampment, outside Rilporin, Wheat Lands

‘The siege progresses as expected, Sire.’ Galtas handed him the distance-viewer and waited while he scanned the wall, the men scurrying across its top and around its base like ants. ‘We are making good progress.’

‘Are we?’ Rivil turned a sour look on him, slapping the viewer in the palm of his hand and no doubt shaking the lenses out of alignment. ‘Are we really? Does it feel like that to you? Because it feels to me like we’ve been sitting on our arses for three weeks while our men attempt the wall and fail. Over and shitting over again.’

‘The siege towers are making a difference now,’ Galtas began, ‘and the trebuchets are definitely having an effect. You can see the defacement of the wall to our left of the gatehouse.’

‘Having an effect. Defacement,’ Rivil sneered. ‘You realise we’re destroying my fucking city in order to conquer it, don’t you? Or at least, we’re attempting to.’ He threw up his hands. ‘Why did I ever let you talk me into this mad scheme?’

Because you didn’t have a plan and your military mind consists of how many wagonloads of luxuries you can take on campaign rather than soldiers or weapons. Because you’re a spoilt little shit who’s never done a day’s work in your life and couldn’t plan a siege if your life depended on it. Oh wait, it does.

So does mine.

‘General Skerris approaches,’ Galtas said instead of voicing any of the thoughts hurtling around his brain.

The fat general of the East Rank wobbled to attention and saluted. ‘Prince Rivil, Lord Galtas,’ Skerris wheezed, ‘we’re about ready for another push, if you’d like to give the order? The Mireces are readying their new tower after the … mishap with the first. Trebuchets will keep up the bombardment until the troops are within range, then cease fire to avoid casualties. Our target is Second Last—’ he pointed a fat finger at Second Tower and Last Bastion, the section of wall to their left of the gatehouse. ‘The Mireces will assault Double First.’ He indicated First Bastion and First Tower to their right.

Skerris’s words conjured a vivid image of the Mireces’ first siege tower bright with flame as the defenders’ fire arrows lodged in the unprotected wood. It’d burnt fast and hard, killing several of the Raiders inside it. A fucking shambles.

‘Defenders’ll have to split their forces again. If we can establish a decent bridgehead this time …’ Skerris trailed off as Rivil’s scowl returned.

‘How many men have we lost so far?’ he snapped.

‘Some hundreds, Sire.’

‘It’s too slow, Skerris. All of this is too slow. We might have destroyed the West and North Ranks, but that incompetence at the harbour two weeks ago allowed fucking thousands of South Rankers into the city to reinforce the defenders. What if they’ve sent for the rest?’

‘Sire, we are doing all that we can. Progress is steady. Yesterday we held a bridgehead for the better part of three hours,’ Skerris added.

‘What do you want, a fucking medal?’ Rivil shouted. ‘We’re running out of artillery for the trebs and a bridgehead is not a bridgehead unless it accomplishes something other than the deaths of our men.’

‘Standard divide and conquer, Sire, and the same tactics will apply if the remainder of the South Rank does come. It may not look like it, but we’re doing well. We’re winning.’

It was probably the worst thing Skerris could have said. Rivil’s face purpled and saliva flew. ‘Winning? Does this look like fucking winning to you, fat man? We’re living in tents and shitting in fields while they live off the provisions of an entire city. They have months of supplies in there, hospitals, armouries, inns and cooks and clean clothes …’

Rivil stopped talking, and neither Galtas nor Skerris moved to fill the silence. Rivil’s temper had been shortening by the hour this last week. He faced the city again just as the lead trebuchet unloaded its stone at the wall. The ground in front was littered with spent boulders and giant slabs of rock that had been cracked off the outer face, all of which further hindered the ladder teams and siege towers.

‘Skerris, send the men, ours and the Mireces. Full assault. Galtas, you’re going with them.’

Galtas sputtered a laugh. Go into the city? As part of a ladder assault? ‘Sire, I’m not Rank-trained. I’ll be too slow up the ladder. I could better serve—’

‘The gods will watch over you,’ Rivil interrupted. ‘So you need not be afraid. If the Mireces have the balls for it, I’m sure you do too. I want you in Rilporin and I want definitive proof that my father is dead. These bastards are too motivated for my liking; the king clinging to life might be enough for them. Then I want you to do something to get us in, either frontal assault or a quiet infiltration. Either will suit.’

‘Do something?’ Galtas echoed. ‘Such as?’

Rivil snarled at him: ‘Improvise.’

Galtas’s face was wooden, unresponsive, but he managed a bow and plastered an insincere smile across his mouth. ‘As you command, Sire,’ he said stiffly. ‘I’ll see to the orders immediately. General, shall we?’

He stalked across the field towards the half of the Third Thousand whose turn it was to die today, his ears straining behind him for Rivil’s voice telling him he was joking. It didn’t come. Galtas would be running up the inside of a siege tower and out across a gangplank on to the wall while archers loosed shaft after shaft at him, or he’d be scaling a ladder along with the Rankers, up into enemy territory with arrows, rocks and boiling oil being poured down on his head, to roll on to the allure and face a thousand defenders.

Galtas was going to die.