Полная версия:

Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989

POST WALL

POST SQUARE

Rebuilding the World after 1989

Kristina Spohr

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Kristina Spohr 2019

Cover design by Heike Schüssler

Kristina Spohr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

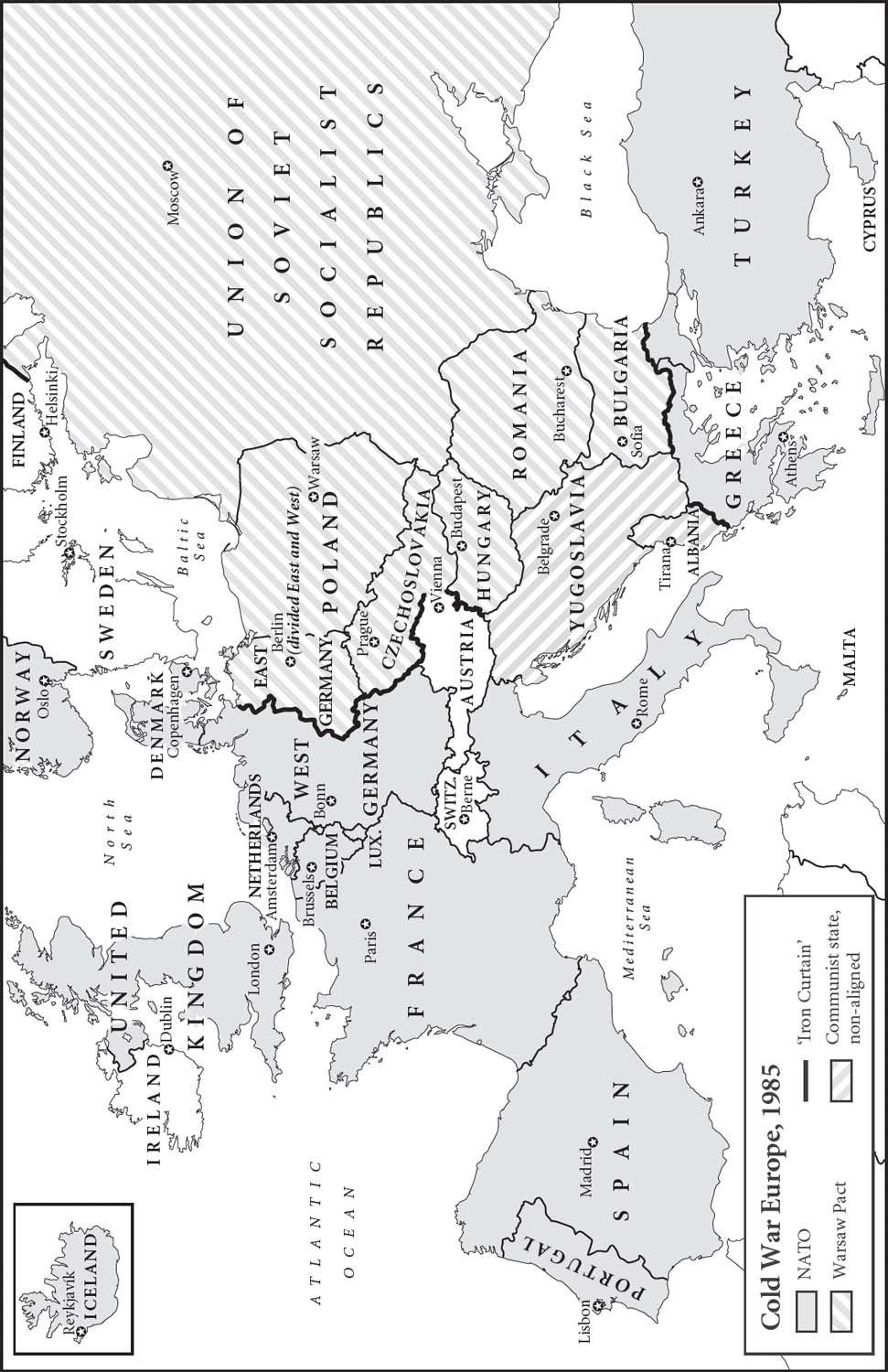

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008280086

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008280109

Version: 2019-09-11

Dedication

For my godchildren

Anna Lisa (*1997)

Daniel (*2004)

James (*2007)

Clio (*2013)

born into the post-Wall world

Epigraph

If 1989 was the year of sweeping away, 1990 must become the year of building anew.

James A. Baker, 1990

We don’t care what others say about us. The only thing we really care about is a good environment for developing ourselves. So long as history eventually proves the superiority of the Chinese socialist system, that’s enough.

Deng Xiaoping, 1989

France is our homeland, Europe is our future.

François Mitterrand, 1987

Peace is not unity in similarity but unity in diversity, in the comparison and conciliation of differences.

Mikhail Gorbachev, 1991

Politics needs a sense of the possible, also of what is acceptable to others.

Helmut Kohl, 2009

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

List of Maps

Introduction

1 Reinventing Communism: Russia and China

2 Toppling Communism: Poland and Hungary

3 Reuniting Germany, Dissolving Eastern Europe

4 Securing Germany in the Post-Wall World

5 Building a Europe ‘Whole and Free’

6 ‘A New World Order’

7 Russian Revolution

8 ‘Dawn of a New Era’

9 Glimpsing a ‘Pacific Century’

Epilogue: Post Wall, Post Square: A World Remade?

Abbreviations

Footnotes

Notes

Index

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Kristina Spohr

About the Publisher

Maps

Cold War Europe, 1985

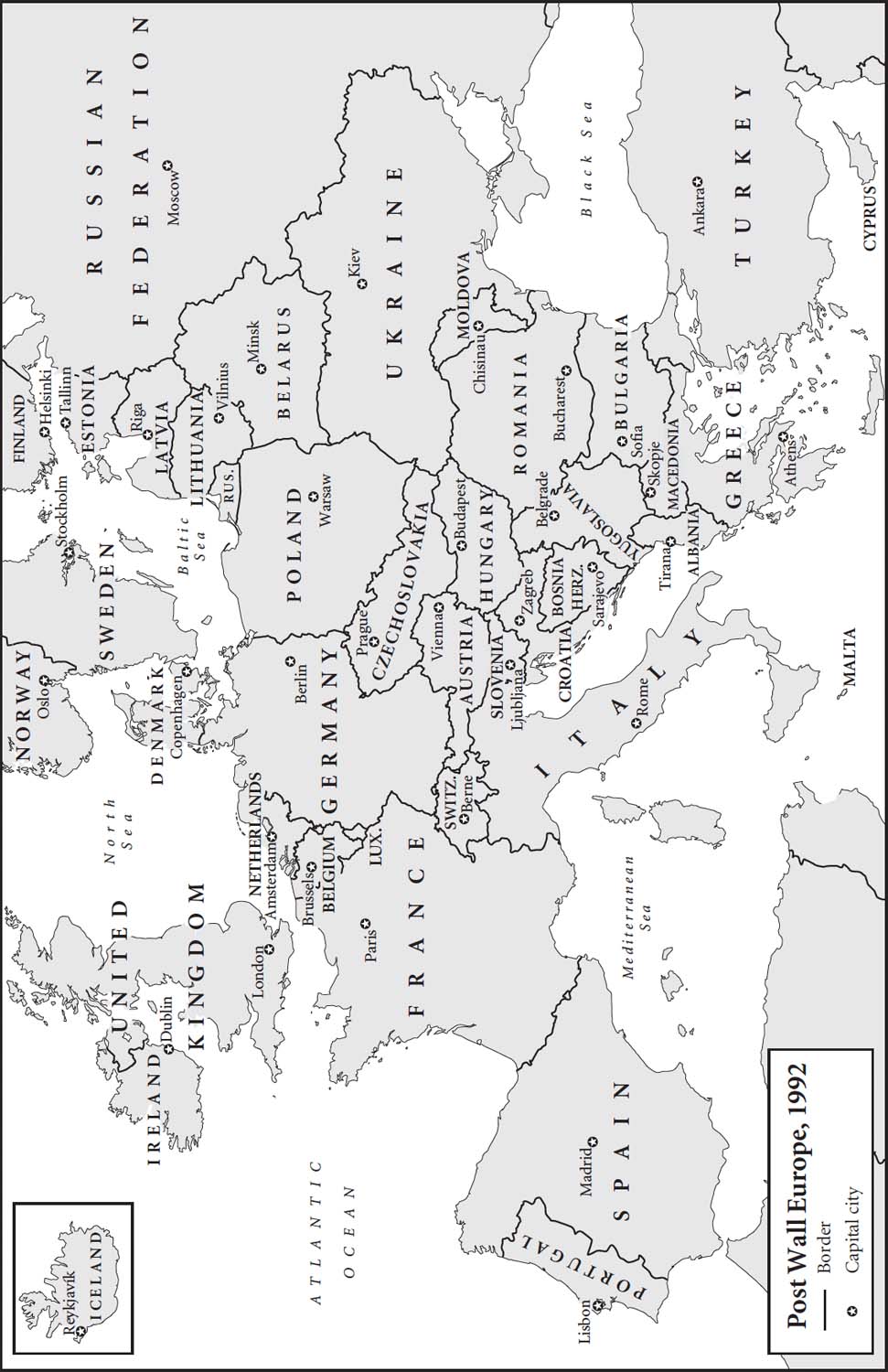

Post Wall Europe, 1992

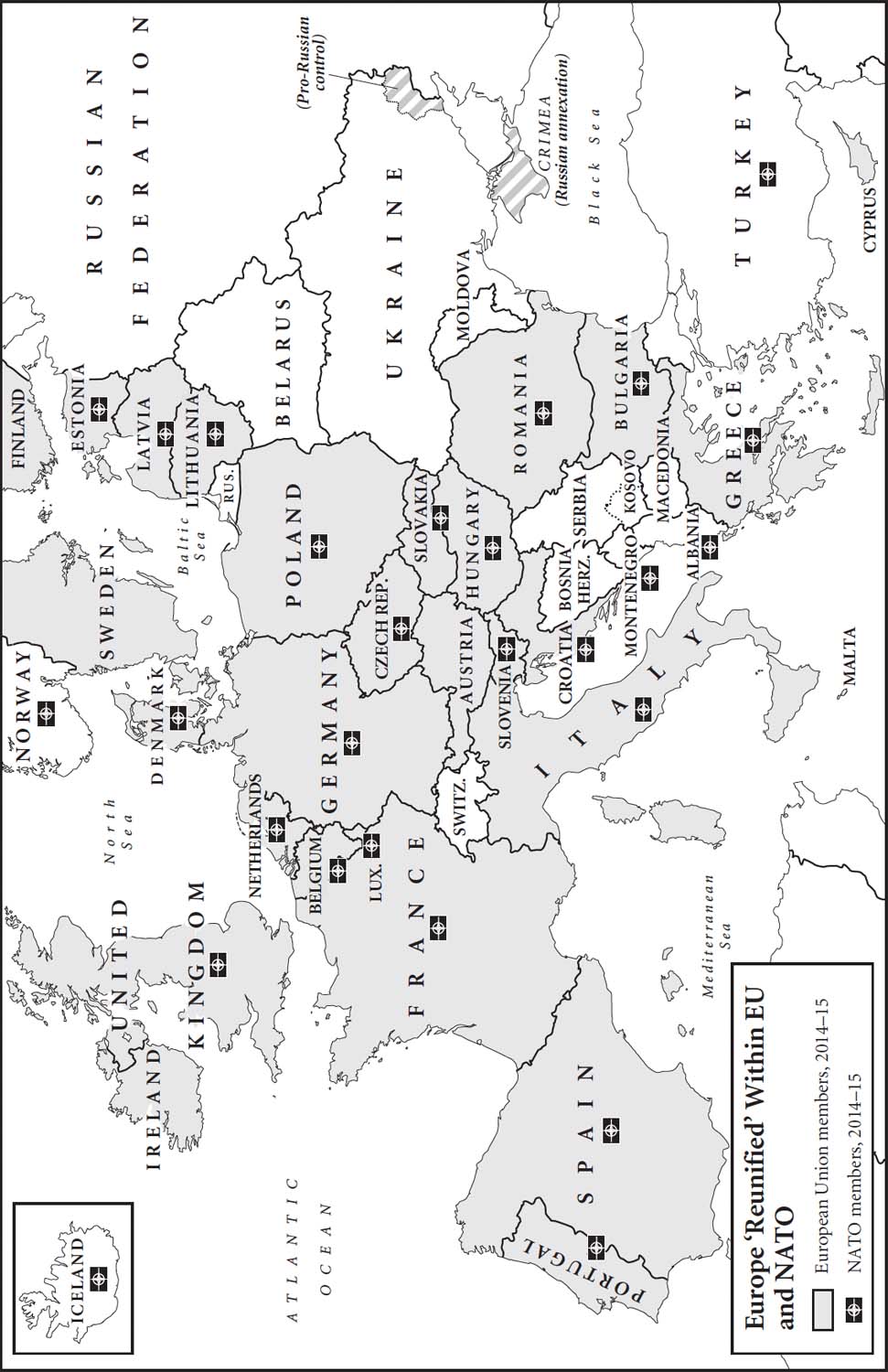

Europe ‘Reunified’ within EU and NATO

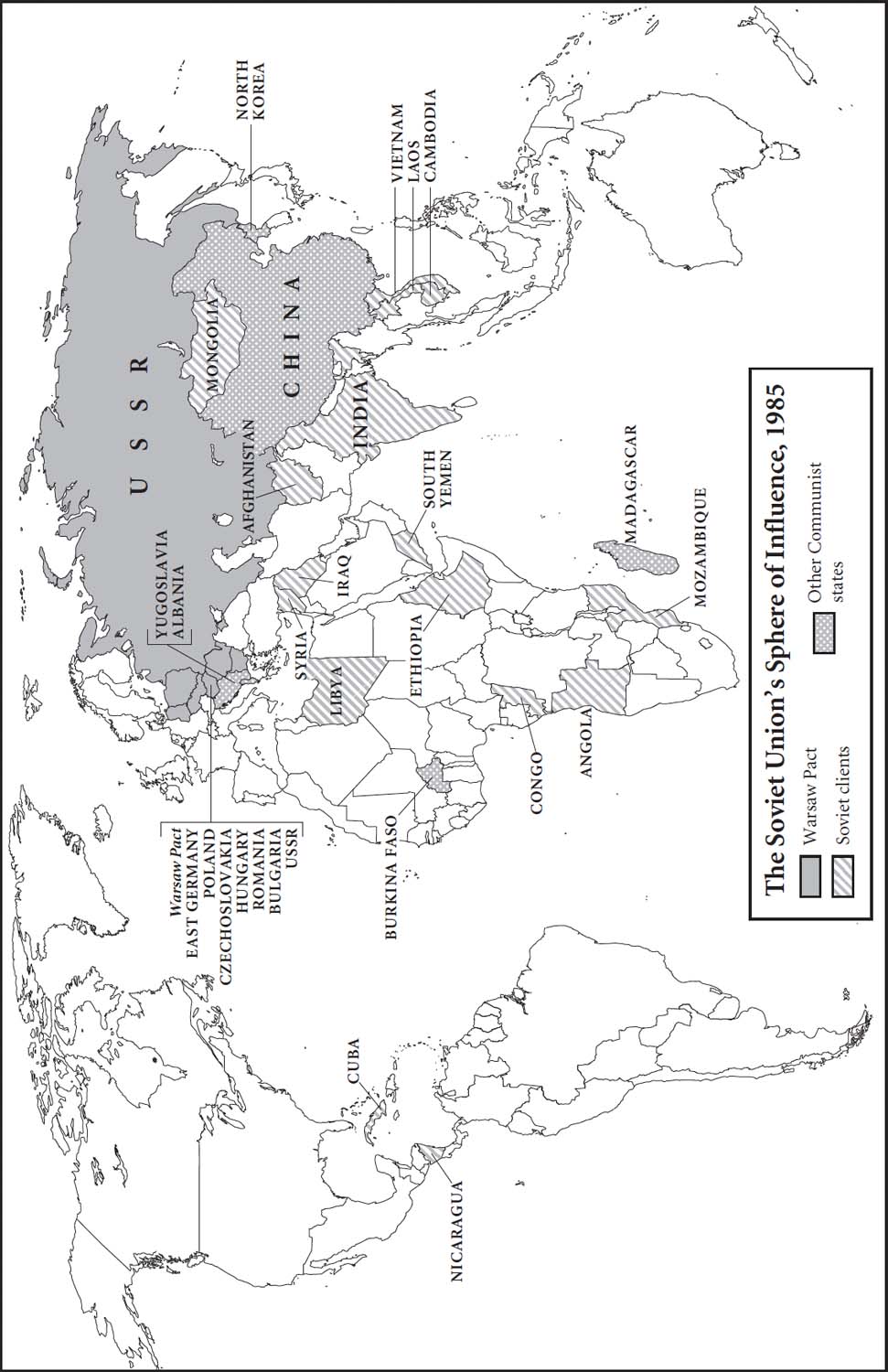

The Soviet Union’s Sphere of Influence, 1985

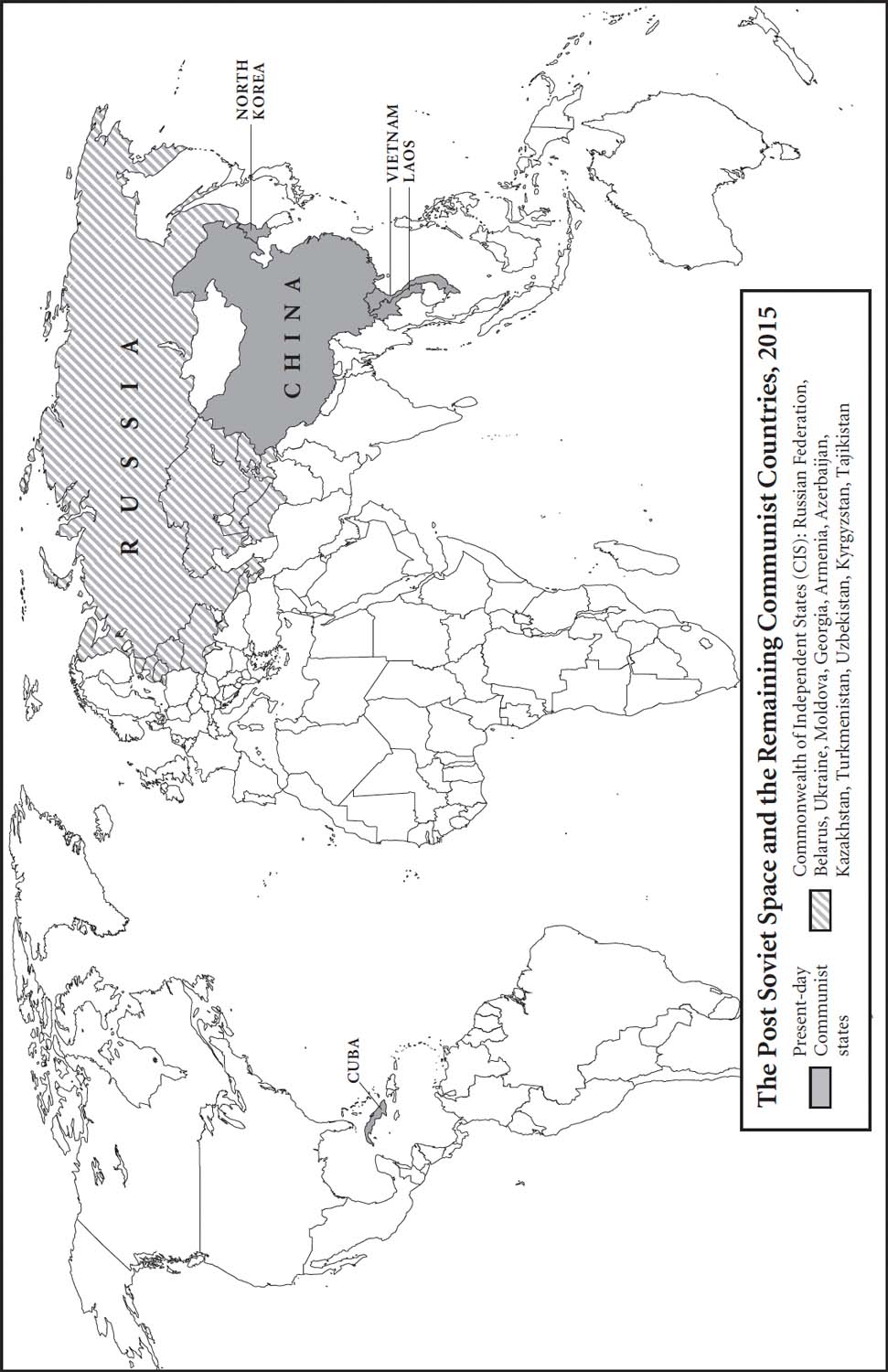

The Post Soviet Space and the Remaining Communist Countries, 2015

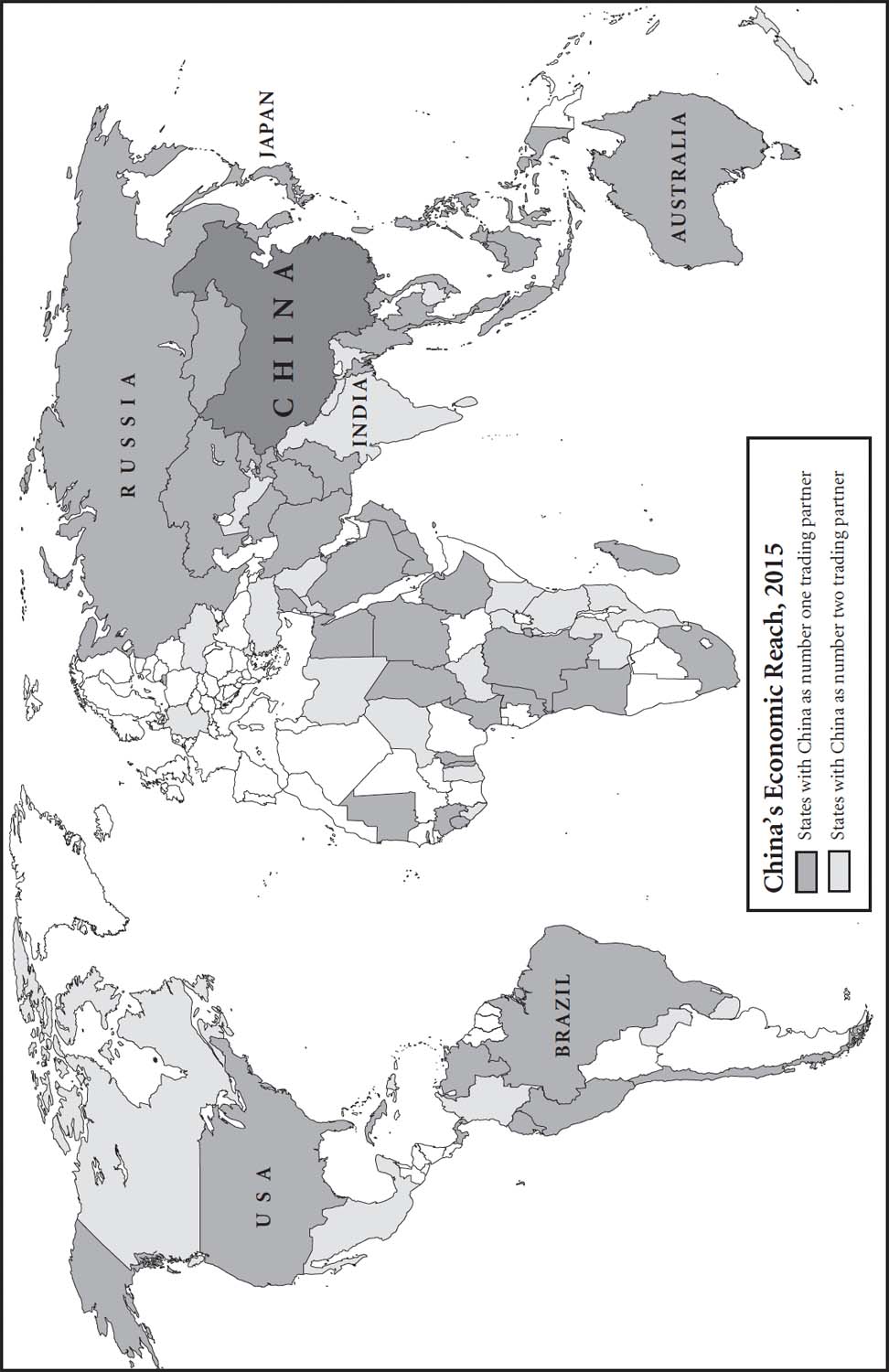

China’s Economic Reach, 2015

Introduction

Economic crisis in the Soviet Union … War in the Gulf … Chaos in Yugoslavia … A Stalinist coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev … Mobilisation across the whole Eastern bloc … Soviet invasion of the Balkans … The West calls up reservists and puts civil defence on highest alert …

At dawn on 24 February 1989, thousands of Warsaw Pact tanks begin rolling into West Germany, from the Baltic right down to the border with Czechoslovakia. The main attack comes across the North German Plain, with a secondary strike toward Frankfurt. At first Western armoured forces manage to keep the enemy in check, despite a tidal wave of refugees. But then the Kremlin resorts to the use of poison gas against Great Britain and northern Germany. On 5 March, Allied forces start to break and NATO authorises the first use of tactical nuclear weapons. Undeterred, the Soviets press home their attacks, so NATO moves to a second and this time massive nuclear strike on 9 March with twenty-five nuclear bombs and missiles, a third of which are launched from West Germany. The Soviet leadership reciprocates in kind. An atomic firestorm engulfs most of West and East Germany. The radiation spreads across Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary …[1]

Of course this was not what really happened. It was the storyline for NATO’s biennial ‘Wintex’ war game. In the 1989 scenario Germany became the theatre of a ‘limited nuclear war’, which meant instant obliteration for hundreds of thousands of Germans, and radioactive contamination across the historic heartland of Europe condemning millions more to a lingering, agonising death. Worse, the spectre loomed that localised nuclear conflict might ignite the Third World War.

Even before the war game had begun, the Wintex 89 drill narrative had been leaked to the press and then sensationalised in the German and Soviet media. So appalling was the prospect sketched out in the simulation that Waldemar Schreckenberger – the man from the Chancellery chosen to play commander-in-chief (Bundeskanzler übungshalber) during the exercise while the real chancellor was busy conducting West Germany’s normal government business – refused to launch the second strike in an effort to curtail the human tragedy. As a result, Wintex 89 was prematurely aborted. There would be no more NATO Wintex drills in the future.

At the beginning of 1989 the Western defence establishment still took seriously the prospect that the long superpower confrontation might climax in a global nuclear holocaust. Only a few months later, however, the European future looked radically different. The Cold War did indeed come to an end in a rapid and unexpected fashion – but not with the nuclear ‘big bang’ for which the two armed camps had spent so much time, money and ingenuity rehearsing.

The war between East and West never did take place; the Cold War denouement was a largely peaceful process, out of which a new global order was created through international agreements negotiated in an unprecedented spirit of cooperation. The two chief catalysts of change were a new Russian leader, with a new political vision, and popular protest in the streets of Eastern Europe. People power was explosive, but not in the military sense – the demonstrators of 1989 demanded democracy and reform, they disarmed governments that had seemed impregnable and, in a human tide of travellers and migrants, they broke open the once-impenetrable Iron Curtain. The symbolic moment that captured the drama of those months was the fall of the Berlin Wall on the night of 9 November.

In 1989, everything seemed in flux. Currents of revolutionary change surged up from below, while the wielders of power attempted political reform at the top.[2] The Marxist–Leninist ideology of Soviet communism, once the mental architecture of the Soviet bloc, haemorrhaged credibility and rapidly lost grip. Liberal capitalist democracy now seemed like the wave of the future: while the ‘East’ embarked on a ‘catch-up’ transformation in Western Europe’s image, the world appeared set on a path of convergence around American values. There was talk of ‘the end of history’.[3]

Nothing had prepared international leaders for such swift and all-encompassing change. For decades they had played war games like Wintex 89. They had never formulated a scenario for a peaceful exit from the Cold War; at worst they just had a fictive military strategy for surviving nuclear Armageddon or, at best, diplomatic tactics for managing a muddled competitive coexistence between two adversarial blocs. They could scarcely have been less prepared for the actual ending that came in 1989–91. This book explores why a durable and apparently stable world order collapsed in 1989 and then examines the process by which a new order was improvised out of its ruins.[4]

In order to understand the paths they took and the decisions they made, I peer over the shoulders of key statesmen, watching them struggle to understand and control the new forces at work in their world. These men (and one woman) explored a range of often-conflicting options in an effort to manage events, impose stability and avoid war. Lacking road maps or shared blueprints for a future world order, they adopted an essentially cautious approach to the challenge of radical change – using and adapting principles and institutions that had proved successful in the West during the Cold War. This was undoubtedly a diplomatic revolution, but conducted – paradoxically perhaps – in a conservative manner.

The leaders involved were a small, interconnected group. In Europe, the triangle that particularly mattered was formed by the Soviet Union, the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany: on one level, the political leaders – Mikhail Gorbachev, George H. W. Bush and Helmut Kohl;[5] on another their foreign ministers – Eduard Shevardnadze, James Baker and Hans-Dietrich Genscher.[6] It was within these fields of force that post-Cold War Europe was shaped. On the margins were two potent but increasingly isolated figures: Margaret Thatcher in Britain, who opposed the rapid unification of Germany, and the French president François Mitterrand, who reluctantly participated on the condition that a united Germany must be deeply embedded in Europe.[7] Their interactions with Kohl, especially over the project of European integration, formed a further power-political triangle.[8]

Yet it is a central assertion of my book that we cannot understand post-Wall Europe without taking account of what happened in 1989 on the other side of the world. Under Deng Xiaoping, the People’s Republic of China experienced a dramatically different exit from the Cold War – forever synonymous with the bloodshed in Tiananmen Square on 4 June.[9] China’s gradual entry into the global capitalist economy was therefore counterbalanced by Deng’s determination to maintain the dominance of the Communist Party. This balancing act – so different from Gorbachev’s complete loss of control – moved his country into another orbit. The people power that had played such a central role in Eastern Europe had no analogue here. Deng’s ‘success’ in suppressing it had vast implications that are still being played out in today’s world. So, the European story has to be framed within another, global triangle – itself a continuation of the Sino-Soviet-American ‘tripolarity’ that was emerging in the later stages of the Cold War.[10]

Taken as a whole, these managers of change formed a cohort largely from the same generation, born between 1924 and 1931, with the exceptions of Mitterrand (b.1916) and Deng (b.1904). All of them were marked by the memory of a world at war between 1937 and 1945 and thus shared an acute awareness of the fragility of peace. It is noteworthy that most of them (Kohl and Mitterrand were exceptions) also lost power in 1990–2, so they were never obliged to confront in a sustained way – as political leaders – with the fallout from their actions.

My first three chapters deal with the headline-grabbing upheavals of 1989 – the cutting of Hungary’s Iron Curtain with Austria, the bloodbath in Tiananmen Square, the accidental fall of the Berlin Wall. But the main focus is on what happened in the exhilarating yet alarming era that followed: the era of the post-Wall and the post-Square. The hope that humankind was entering a new age of freedom and sustained peace competed with the dawning recognition that the bipolar stability of the Cold War era was already giving way to something less binary and more dangerous.[11]

The core of the book traces the story of how in 1990–1 the world was reshaped by conservative diplomacy – adapting the institutions of the Cold War to a new era. Although this was led by the West, and particularly by US president George Bush, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was also willing to buy into the process as part of an effort to reorient the Soviet Union’s official ideology towards the ‘common’ values Soviet citizens shared with the West.[12] The resulting rapprochement culminated in a brief era of unprecedented cooperation between the US and the USSR. Their collaborative approach to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 was to serve as the centrepiece of what the American president described as the ‘new world order’. Confrontational bipolarity appeared to be metamorphosing into a two-pillar approach to global security, rooted in superpower cooperation within the United Nations and guided by international law.[13]

Both Bush and Gorbachev hoped that this new modus vivendi could serve as the foundation for post-Cold War international relations. America was clearly the senior partner but the cooperation was real. The partnership worked, but it was fragile, precisely because it was overly focused on the relationship between the two men at the apex of their respective states. Bush, Kohl and other Western leaders all clung to Mikhail Gorbachev rather than engaging with the deeper problems of the unravelling Soviet Union. At the end of 1991, the USSR totally disintegrated, forcing Bush to take seriously the man at the helm of post-Soviet Russia, Boris Yeltsin – who was struggling to confront the immense challenge of his country’s transition to capitalist democracy.[14] This new upheaval in global geopolitics, affecting not only Europe but also Asia, obliged Bush to rethink his two-pillar approach.

With the Soviet Union gone and bipolarity a thing of the past, the United States was now pressing with fresh urgency for a truly global US-led free-trading system. Intended to replace the almost moribund 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) which no longer seemed adequate to the dynamics of an increasingly globalised world economy, a new World Trade Organisation should embrace the big players Russia and China as they moved out of their respective command economies or ‘Plans’, and offer more support to the developing countries. Yet the US was not alone in seeking to reposition itself in the global economic power play. Japan, with its prodigious economy, was touted as the coming hegemon of the ‘Pacific Century’, whose economic weight would fill the geopolitical vacuum created by the collapse of the Soviet Union. The leadership of communist China had its own ambitions. The Chinese regime survived ‘the Tiananmen Incident’, consolidated its hold on the country and prospered post-Square; over time this would prove far more important, both economically and geo-strategically, than the false dawn of the Rising Sun.[15]

In Europe, too, the peace and stability of the post-war era were starting to fray in 1991 when Yugoslavia became engulfed by a genocidal war. A once firm Balkan polity fractured into warring statelets, triggering massive movements of refugees. These new Balkan wars did not ignite a European or global conflagration, as in 1914, but international leaders struggled to put out the flames.[16]

The splintering of Yugoslavia also raised fears of what Gorbachev himself called the ‘Balkanisation’ of the Soviet Union in 1991.[17] For a while Moscow’s power struggle with Kiev over territory in Ukraine and Crimea seemed even to teeter on the edge of war. Disputes and clashes erupted during 1992 about ownership of the Black Sea Fleet and strategic ports, Russian basing rights and the use of Ukrainian military facilities. And Washington was particularly anxious about the fate of the Soviet nuclear arsenal – now scattered between Russia and three other newly independent post-Soviet republics.

The collapse of Soviet power allowed former clients around the world to assert themselves as ‘renegade’ states. Even after the Kuwait War of 1990–1, the problem of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq remained unresolved, and Kim Il-sung’s North Korea, with its secret nuclear weapons programme, now became a particular headache.[18] This is why the last two chapters of Post Wall, Post Square are devoted to global events in 1992 – a year largely ignored in most accounts of the end of the Cold War, in which problems were spawned that are still with us in the twenty-first century. Notwithstanding the premature triumphalism of some commentators, the Cold War did not end with the simple victory of the United States over the Soviet Union, and the world was not remade in America’s image.[19]

Nowhere did international diplomacy produce swifter and more impressive results than in the unification of Germany. The German question posed a huge challenge because of the country’s problematic place in Europe, its centrality to the origins of two world wars and its subsequent position as the cockpit of the Cold War. In the process of managing German unification, two key alliances of the West during the Cold War – NATO and the European Community – were conserved, modified and eventually enlarged to encompass the states of Central and Eastern Europe.[20]

The measures adopted to stabilise post-Wall Europe were thus essentially conservative in character, in the sense that they made use of pre-existing, Western institutions and structures, rather than custom-designing new ones to meet the exigencies of a new era. Despite the efforts of some European statesmen – notably Genscher, Gorbachev and Mitterrand – in 1989–91, no new pan-European architecture was created to embrace the two halves of the continent and incorporate Russia into a shared security structure. The Helsinki 1975 Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) possessed the potential to become such a structure, but it was never converted into an operative security organisation. The post-Wall political reality – with America set to remain a ‘European power’ – conspired against such pan-European paths. And the attractions of a Europe reunified under the aegis of an ever-closer European Union and secured by a reinvented NATO were simply too strong.[21]

Consequently, the West–East asymmetry increased over time, as the jumbled fragments of what had been the Cold War order were re-formed within an ever-larger Western-dominated framework. The resulting imbalance would become intolerable for Gorbachev’s successors, Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin. A marginalised – though still powerful and status-conscious Russian rump state – was left to lick its wounds on the periphery of the new Europe. We are still grappling with the consequences.[22]

This rereading of the period 1989–92 draws on archival material in various languages from both sides of the former Iron Curtain. Post Wall, Post Square relies heavily on recently declassified or neglected documents – ranging from memoranda to memcons, from personal letters to intelligence reports – in the national, presidential and Foreign Ministry archives of the United States, the Soviet Union (Russia), Germany, Britain, France and Estonia. Other important resources include the National Security Archive, the Woodrow Wilson Center Digital Archive and the associated Cold War International History Project in Washington DC – with their abundance of electronic briefing books and published documentary collections from the West, Eastern Europe, Russia and China (including party and Politburo materials). Further primary sources include diaries and private papers by the leaders and their advisers and numerous memoirs by the major actors.[23]

Post Wall, Post Square combines the granular reconstruction of key episodes with the synoptic study of macro-historical change. To comprehend properly this era of transitions requires us to adopt an artificial vantage point ‘above’ the confusion of events. But a successful analysis must also find space for the narratives with which leading protagonists made sense of their world and justified their actions. After all, the story of what happened in those years was ‘co-written’ by the chief actors. They were never just players in someone else’s tale, but powerful, if flawed, makers of history in their own right.

In 1995 German president Roman Herzog characterised his era as ‘a time that as yet has no name’.[24] Twenty-five years later, his aphorism has lost little of its poignancy, because the distinguishing features of the post-Cold War era remain difficult to discern or understand. Some may say, as 1989 recedes into the past, that the overarching narrative must be economic – taking us from the collapse of the Bretton Woods financial system in the 1970s to the financial crash of 2008.[25] But I argue that a deeper analysis of these crucial ‘hinge years’ of 1989–92 helps to make sense of the underlying geopolitical order in which the upheavals of global capitalism take their place. And it is this order that is now under threat.

The achievements of the conservative managers were impressive: above all, they stabilised Central Europe during a period of rapid geopolitical change. But the (mainly American) confidence that the world would henceforth converge towards US values in an increasingly Washington-centred global order has not stood the test of time. The notion that an aggrieved but resurgent Russia[26] or the People’s Republic of China – always following its own compass[27] – would accept subordinate status in a unipolar world now appears hopelessly naive.[28] And the Europe of the Maastricht Treaty failed to generate the vision and energy to create a continent that was whole, free and dynamic. It was cramped by its adherence to dogmas forged after 1945 and hobbled by its chronic lack of independent political and military power.

This new European Union of 1992 co-opted the logic of the West German state’s post-war trajectory. The Federal Republic had long renounced Germany’s historical pretensions as a military power. European integration was conceived in the 1950s as a German–French peace project built around economic prosperity and social welfare. As the EU sought to reap the post-Cold War peace dividend in the 1990s, it saw itself in German mode as a beacon of ‘civilian power’[29] – not of military might.

This represented a linear reading of the post-Wall future, extrapolating the peaceful unification of Germany onto the European plane. But the plausibility of this eirenic dream has been called into question by the rise in the 2010s of populism, nationalism and illiberalism – with ‘Brexit’ shaking the core belief that the European integration project is irreversible and US President Donald Trump undermining the presumed indestructibility of the transatlantic alliance. The American vision of a ‘global community of nations’[30] – an order based on international law, liberal values, the limited use of force and a legitimate international arbitrating authority – now looks utopian.[31] The old great power rivalry is back with a vengeance and the traditional Western verities of democracy and free trade are being challenged around the world – especially by Russia and China, but also by America itself.