скачать книгу бесплатно

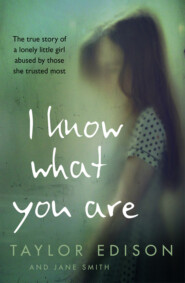

I Know What You Are: The true story of a lonely little girl abused by those she trusted most

Jane Smith

Taylor Edison

The moving true story of a little girl with Asperger syndrome, controlled and abused by the one person she called her friend.Taylor had always struggled to make friends – she felt ‘different’. Taylor never knew her father and her mother wasn’t around much. She just didn’t understand people, and was alone and scared most of the time.That was until, aged just 11, an older married man called Tom befriended her. She loved having someone who would talk to her, listen to her, a protector. But when he moved away a few months later she was easy prey to the gang of drug dealers and petty criminals who groomed and abused her, using her as a form of currency to appease their debtors and amuse their friends.Increasingly isolated and desperate, it began to look as though the pattern of Taylor's life had been set – until she started to fight back, determined to build a safe future for herself, however long it took.

(#u8e3adb8e-bdb6-524d-bda5-7127df3c8be2)

Copyright (#u8e3adb8e-bdb6-524d-bda5-7127df3c8be2)

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2017

FIRST EDITION

© Taylor Edison and Jane Smith 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover photograph © Mark Owen/Trevillion Images (posed by model)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Taylor Edison and Jane Smith assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008148027

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780008157388

Version: 2016-12-20

Contents

Cover (#u2b68b1c6-d742-5005-b8aa-7990ef18b8ce)

Title Page (#u5d4aeea9-d2be-5b93-8037-47b937ed01dc)

Copyright (#uf244c56f-f775-59a4-8d3a-be850a56bc61)

Preface (#ufbdfeb0a-bdce-56d9-9cf0-2e793baa913a)

Chapter 1 (#ue7297c15-c3ec-5293-8e8d-fb3ce8ecebb8)

Chapter 2 (#u7d84c92c-79d4-5da9-8241-90fd21f61eba)

Chapter 3 (#u8ebb5cee-77b2-540c-a16b-b2adc30bc783)

Chapter 4 (#uc9fcde4e-7734-587f-b43a-12da3138ee49)

Chapter 5 (#uc9b017ad-5d0f-5374-bf1d-1d0e00fc9816)

Chapter 6 (#u87931937-5c85-5598-a6fd-43b81c3aac94)

Chapter 7 (#u464430bb-3520-5ece-b223-08059ecf4842)

Chapter 8 (#u9bc75bde-d0f1-5dfe-8f95-ed966224be7d)

Chapter 9 (#u1132f08f-734b-51c8-beea-bb678c9bf0ab)

Chapter 10 (#uff64abfe-83e4-5cfe-a981-71517f732d21)

Chapter 11 (#u3dd04239-ed86-543e-aea4-df545230a5a6)

Chapter 12 (#u4be2d841-b19b-568e-878c-c3c709d80032)

Chapter 13 (#u126f4143-5f0b-5c83-90d8-bf48aa8e7dc2)

Chapter 14 (#u768fe1e4-8aa2-5ef5-be35-8e9b90f25c59)

Poems by Taylor Edison (#u8ffa002b-72fb-5b30-b21c-cdc56f1d4a18)

About the Author (#u9a09ca6c-36da-580e-9b39-16e0c63e7880)

Moved by I Know What You Are? (#uf2bd2a79-a06b-5dad-a157-2b7fe45420cb)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#u74c71723-62ba-5d78-9ba9-d717b2830c82)

About the Publisher (#u8571c1ed-82a9-5113-8c93-3aedc76a8a92)

Preface (#u8e3adb8e-bdb6-524d-bda5-7127df3c8be2)

I used to feel angry with my mum because she didn’t intervene in what was going on when I was a child. But I realise that she’s got problems of her own and I just feel sorry for her now. What made me look at things differently was becoming a mum myself: I try really hard to do what’s best for my child – it’s just a natural instinct; so I think my mum must have been trying hard too.

I would have liked to have told my story without mentioning Mum at all, and especially without saying anything negative about her. But because most of it deals with abuse that occurred during my childhood, that would have made it seem as though she wasn’t there while I was growing up. And that isn’t true. So I’m just going to tell it the way it happened.

There are lots of reasons why people fall victim to abusers. In my case, it was partly because I have a type of autism called Asperger syndrome, which means that I have ‘significant difficulties in social interaction and non-verbal communication’. In other words, if someone tells me they’re my friend, for example, I believe them, even though the way they’re treating me is anything but friendly.

Friends have been a significant factor in my life – because I desperately wanted them as a child, because I didn’t know how to make them, and because my ‘social interaction and non-verbal communication’ problems meant that, for a long time, I wasn’t able to distinguish between my friends and my enemies.

I can’t change what happened to me from the age of 11. I know that some of it will continue to have an effect on me for the rest of my life. But I do try really hard to remember that I am not the bad person I believed I was when I was a little girl.

What’s crucially important when you have experienced abuse is to try not to define yourself in terms of ‘bad things happened to me as a child because I was a bad child’. That’s why I want to tell my story, because I hope it will help other people to realise that what is done to you isn’t what you are.

Chapter 1 (#u8e3adb8e-bdb6-524d-bda5-7127df3c8be2)

I was two years old when Mum and I moved into the flat that quickly became a doss-house for an assortment of her weed-smoking friends. I didn’t have a bedroom of my own in that flat; my bed was wherever I happened to fall asleep each night, which was usually on the sofa or floor in the living room. Fortunately, Mum’s friends were nice to me and there was always someone who was willing (and able) to feed me when I was hungry or put me in the bath when I needed a wash. So I was perfectly happy, as far as I remember. Until I started school.

Because I had assumed – as children tend to do without even thinking about it – that what happened in my own home was ‘normal’, school came as a complete shock to me, for many reasons. As I hadn’t really mixed with other kids before I started school, I didn’t know how to make friends or even how to play with other children. And I wasn’t used to being shouted at the way my teacher shouted at me on my very first day when I didn’t do something she had told me to do.

I wasn’t being deliberately disobedient or naughty. I just didn’t understand what she meant. I was used to being given simple directions by my mum and her friends – ‘Stop it’, ‘Eat it’, ‘Go to sleep’ – and I was bewildered by the teacher’s collective instructions to the class, which became even more incomprehensible to me when she said things like, ‘Unfortunately, we won’t be able to go outside at playtime today as it’s still raining cats and dogs.’

It didn’t matter how hard I tried to understand what I was supposed to be doing, I invariably seemed to get it wrong. So I was always either already in trouble or feeling sick with apprehension, which meant that school was pretty much ruined for me right from the start.

Another thing I hated about school was that it meant being away from my mum, which was something I wasn’t used to, although that was true for most of the other children too, I suppose. I don’t have many specific memories of my mum when I was a young child, but I know she was almost always there – in body, if not in spirit – and that I never spent a single night away from home when I was a little girl. In fact, Mum and I had a very close relationship at that time, and even though it might have been odd and dysfunctional in some ways, at least it was familiar and comprehensible to me. I could tell when she was angry, for example, and I usually knew why; while she knew how to talk to me in a way that I could understand and that didn’t trigger a meltdown in my weirdly wired brain.

But I didn’t understand my teachers, and because the lack of comprehension was mutual, they would often back me into a corner, literally as well as figuratively, so that I felt trapped and panicked. As a result, it wasn’t long before a hostile relationship began to develop between me and my teachers, which, far from trying to rectify, Mum sometimes seemed actively to encourage. After being happy to let other people take care of me since we’d moved into the flat that was always full of her drunk and drug-addicted friends, I think the time when I started school coincided with a phase when she wanted it to be just her and me against the rest of the world. So maybe she resented the influence she thought my teachers would have on me, or perhaps it simply felt as though she was getting her own back on all the teachers she used to tell me about who she hadn’t liked when she was a child.

I didn’t want to be in conflict with anyone though, and as well as trying – and usually failing – not to annoy my teachers, I longed to be like the other kids, who seemed to be able to follow instructions that, to me, seemed impossibly complicated and indecipherable. I hadn’t been at school for very long before I realised that there must be something wrong with me, which I assumed was the fact that I was ‘retarded’, as Mum often told me I was. And that made me even more anxious to learn to behave the way the other kids did, because I really didn’t want to have to go to a ‘special school’ like the one Mum described to me, where they sent children who weren’t ‘normal’.

Even when I was diagnosed as having Asperger syndrome, which was something that apparently couldn’t be ‘cured’, I think Mum still preferred to believe I was ‘retarded’, because that was something she thought I could recover from, if only I tried hard enough. Perhaps her intentions were basically good, in that she was hoping to push me towards normality by refusing to accept that I had a problem. Or maybe she was just hoping that, whatever the problem was, it would go away if we ignored it.

It didn’t go away though. It just got worse, until, eventually, I was so confused, lonely and unhappy I would have done almost anything to feel that my mother loved and approved of me, or that I had just one real friend. And then that became the real problem, because being desperate for affection puts any child in a potentially dangerous situation, particularly a child like me, who was already vulnerable for other reasons.

It wasn’t until I started school that I realised I didn’t have a dad. Even then, it didn’t seem like a huge deal, because I wasn’t the only child whose dad wasn’t around, although I think most of the others at least knew who their fathers were, whereas I didn’t know anything about mine.

I’ve never met my dad and Mum has never talked about him, except to say that he left before I was born. Perhaps he didn’t even know Mum was pregnant and so has no idea that he has been a father for the last 21 years. I sometimes wonder if things might have been better – for Mum and for me – if he had stuck around while I was growing up. I don’t wish he had though, because he might have made things worse, especially if he was an alcoholic or a drug addict, like most of Mum’s friends when I was a child. And, in my experience, getting the thing you wish for doesn’t always turn out well.

Mum was living with someone else when she met my dad, and when she got pregnant he threw her out. So she moved in with her mum, and that’s where I lived, too, from the time I was born until I was two years old.

Grandma was in her forties when she had Mum, and Mum was in her thirties when she had me. So Grandma was well over 70 by the time I was born, and was already suffering from whatever it was that killed her when I was five. I don’t have any clear memories of my grandma. I don’t think she played a very active role in the first few years of my life, because she was ill and because she and my mum didn’t get on.

My only other close relative is Mum’s cousin, Cora, who lived in a flat in the house next door to Grandma. Cora suffers from depression and often finds life a bit of a struggle. But she has always worked hard and has done quite well for herself – which was fortunate for Mum and me, because when Grandma threw Mum out, Cora let us live in another property she owned. I don’t know where we would have gone if she hadn’t helped us, because, unlike her cousin, Mum has never worked or owned anything.

We are the sort of family that doesn’t talk about anything important. So I don’t know what caused Cora’s mental-health problems, or why Grandma and Mum didn’t get on, or why Mum was only able to deal with life at all when she was separated from reality by a haze of cannabis smoke. I do know that I was very difficult as a child. At least, that’s what Mum always told me, and I have to assume it was true, because I was certainly ‘difficult’ a few years later. Even so, maybe it’s something no child needs to be told, and certainly not repeatedly.

Growing up knowing that your mum is having a horrible time and hating every minute of her life is bad enough. Believing that it’s all your fault can provide the momentum that keeps the vicious circle of stress and bad behaviour spinning. It didn’t do much for my confidence or self-esteem either. What made it even worse was the fact that I can’t read or interpret people’s expressions and body language, which meant that, as a child, I simply accepted whatever I was told as fact. Taking everything literally can be confusing at any age, but particularly when you’re a child trying to make sense of the world for the first time. So, as far as I was concerned, I was difficult and I was the sole cause of all Mum’s frustrations, disappointments and anger. Otherwise, why would she have said I was?

Fortunately, after we moved out of Grandma’s place and into Cora’s other property, Mum made friends with a couple who lived in the flat downstairs and who enjoyed smoking weed almost as much as she did. The fortunate bit about it, for me, was the fact that they were happy to help her look after me. Someone who’s pretty much stoned from shortly after her first cup of tea in the morning until she falls asleep at night does need some help taking care of a two-year-old child and, as it turned out, three pot-heads are better than one.

It wasn’t long, though, before our flat had become a doss-house for numerous alcoholics, drug addicts and petty thieves. Having grown up in the 1960s and 1970s, Mum saw it as a sort of hippy commune, which, to her, was something positive. And it did have some positive aspects. But, even taking those into account, it wasn’t a good environment for any child to grow up in, for lots of reasons.

Despite all the pitfalls and potential dangers, however, everyone was very nice to me and I was never abused or neglected while we lived there. Mum’s friends might have been doing irrevocable damage to their own lives and mental health, but they were mostly more ‘peace and love’ than intent on kicking anyone’s head in. So the atmosphere was usually quite relaxed and there was rarely any aggression – as there might easily have been with so many dysfunctional, ultimately self-destructive people living together in one room.

Having so many people dossing in the flat also meant that on the many occasions when Mum was too stoned to remember she even had a child, there was always someone who was clear-headed enough to be able to put me in the bath, get me a drink from the kitchen or take me out to McDonald’s and buy me something to eat.

From the little I know about Mum’s life before I was old enough to understand things myself, I think she was already quite heavily involved with drugs by the time I was born. She told me once that she stopped taking speed and ecstasy when she was pregnant, but that she still smoked a lot of weed. I remembered that recently, when I read something about smoking weed in pregnancy possibly having a negative effect on the development of the baby’s brain and behaviour. I wonder what my life would be like now if I hadn’t grown up believing that all my behavioural problems – and the frustration and distress they caused Mum – were my fault.

After we had been living at the flat for a while, some of Mum’s friends started getting addicted to more serious drugs. I think it was because they were stealing to feed their habit and then got involved with petty criminals and drug dealers who had their own, financial, reasons for wanting to get them hooked on something harder than cannabis. I think that was why things began to take a darker turn at the flat. There was certainly a period Mum has never wanted to talk about. Although I was very young, I have a clear memory that must have been during that time of climbing up on to a man’s knee and not being able to wake him up, then hearing Mum telling someone later that he had overdosed and was actually dead in the chair.

I was too young to understand any of it. So I am not consciously aware of any bad memories associated with that time. Maybe I wasn’t always happy there though, because I tried to run away on at least one occasion. Apparently, I managed to drag my bicycle down the steps at the front of the house and on to the pavement without anyone noticing. Then I cycled to the corner shop and sat with the shopkeeper for a whole hour before he realised no one was coming for me and took me home.

The flat had one bedroom and a high-ceilinged living room that was always full of people sleeping, smoking and drinking. Everyone made a mess and no one ever cleaned it up, except to wash a plate or a cup on a strictly as-needed basis or to scrape up the occasional congealed mess of vomit after someone had been sick in a corner of the room. I didn’t have a bed of my own, so I slept in a drawer until I got too big for it, then in Mum’s bed or on the sofa in the living room, or wherever else I happened to be when I fell asleep amongst all the prostrate bodies.

I thought everyone lived like we did and just accepted it all as normal. I didn’t know anything else, and as none of Mum’s friends had children of their own, I didn’t have any other child’s life to compare with mine. In fact, I had just one friend at that time, a little girl called Judy, who lived a few doors away and was probably 11 years old when I was four. But as her mum was a serious drug addict, my life seemed pretty good compared with hers. Despite never having been looked after in any practical or emotional way herself, Judy took care of her little sister almost from the day she was born, and often fed and played with me too.

Eventually, when I was five, Cora got fed up with her flat being used as a doss-house and told Mum she would have to find somewhere else to live. And as Mum had recently started seeing a guy called Dan, we moved in with him.

The fact that Dan was an alcoholic would have been enough to make him an unsuitable stepfather for any child. But he took the place of the dad I didn’t have and was always good to me. (I always called him my stepdad, although he didn’t actually marry my mum.) Despite his drinking, he was still managing to hold down a job – as a sort of cowboy builder – when we moved in with him. So at least someone was bringing money into the household.

At Dan’s house, I had my own bed at last, in the basement. More importantly though, I had stepsiblings. Dan had two daughters, aged seven and eight, and three sons in their teens, although only the two younger ones ever stayed overnight. Even with my problems interpreting social interaction, it was clear to me right from the start that Dan’s children didn’t like me. Looking back on it now, I suppose they had enough troubles of their own, having to cope with being dumped at irregular intervals by one alcoholic parent on the other. So I must have seemed like a cuckoo in their already overcrowded nest. But I was too young to understand that at the time. I thought it was for purely personal reasons that they would push me down the stairs or wrap me in a blanket and sit on my head until I became hysterical with breathless panic. They may have disliked me too, of course. But, whatever their reasons for bullying and teasing me, I know I was easy prey.

When Dan was at work, Mum usually went out as well, leaving me in the house to be looked after by the other kids, who, when they weren’t tormenting me, took me shoplifting. I imagine all children want to be liked; I was the sort of child who wanted it desperately. And, like any other desperate need, that made me vulnerable. Add to that the fact that I was gullible, naive and totally lacking in social awareness, and you can understand why I was like putty in their hands.

When the adults were out and my stepbrothers took me into town, it was my job to distract the shop assistant in whichever shop they chose as their target for the day. Having been well instructed and rehearsed, I would peer over the counter and say, in my sweetest, most innocent-sounding voice, ‘Excuse me. Can you help me, please? I want to buy a present for my mum.’ Then, while the shop assistant’s attention was focused on helping me, my stepbrothers would be helping themselves to whatever they wanted off the shelves. Surprisingly, perhaps, we didn’t ever get caught, although our success might have been due to the fact that we were taking advantage of the kindness of decent people who didn’t expect to be conned by a five-year-old child, rather than to any great skill on our behalf.

My stepsiblings were supposed to live most of the time with their mum, but she often dropped them off at their dad’s house when she got tired of looking after them or had better things to do. Dan’s eldest son used to visit us sometimes too. I always liked it when he came because, unlike his siblings, he was really nice to me and would spend ages styling my hair and putting varnish on my fingernails. Then, one day, his dad found out he was gay and beat the crap out of him, and he didn’t ever come again.

The only other time I remember my stepdad being as angry as he was that day was when I was six and one of my stepbrothers tried to touch me ‘down there’. Mum thought it was funny – the only time she ever really got angry was when something or someone threatened to disrupt her own life. But my stepdad went ballistic. The next thing I remember is sitting in the car outside a house with a white fence, watching anxiously while he and a woman screamed and shouted at each other. I thought it was all my fault, for some reason I didn’t understand. So, although I was frightened by the row he was having with the woman – who turned out to be his ex-wife – I was a bit relieved too, because Dan seemed to be blaming her for what happened.

Although I think, in that instance at least, both parents were probably equally to blame, Dan’s ex-wife did often push her luck with him in a way that I don’t think my mum would have dared to do. For example, she would sometimes drop the four younger children at our house to stay with their dad for the weekend, then turn off her phone and go missing for a couple of weeks. When I think about it now, it’s hardly surprising my stepsiblings all had behavioural problems: no child should be treated like the prize in a game of pass the parcel that neither of their parents wants to win.

After living in Dan’s place for a while, we all moved into a larger house. I think Dan might have had some connection with the landlord, maybe through his work as a builder, because the house was very old and in such a terrible state that it probably shouldn’t have been rented out at all. It was demolished not long after we lived there, torn down along with a lot of other houses in the area to make way for brand new homes. So I suspect its fate had already been sealed before we moved in.

One of the worst things about the house we lived in with Dan was the bathroom. It was downstairs, next to the kitchen, and its floor was made of bare concrete that stopped short of the bath, so that the legs of the bathtub were resting on soil. Every time it rained, water seeped up through the ground and flooded the room with evil-smelling mud. It would spread to the kitchen too, where the dank spaces under the cupboards were home to an assortment of snails, slugs and woodlice.

It was odd that Mum didn’t seem to mind living like that, particularly in view of the fact that later, when we moved again, she became obsessed with keeping our house clean. Perhaps it was just that a flooded bathroom was the least of her worries, compared to having been landed with four children she didn’t want in addition to the one she already had.

I don’t have many specific memories of Mum either being there or not being there during that period of my childhood. I know she was still smoking a lot of weed, so perhaps she was there more than I remember, but in the background somewhere, unnoticed in the noisy chaos of all the lives being lived around her. What I do remember is that Mum didn’t cook and I was always hungry. She didn’t enjoy cooking, so she simply refused to do it, even when Dan was out at work all day and there were five children who needed to be fed. When Dan was at home, he made just two things: porridge and spaghetti Bolognese. But mostly we ate takeaways.

After we had lived for a few months in the house with the muddy bathroom floor, Dan’s alcoholism began to get really bad. Even when he was working, he must have struggled to pay the bills for all of us, plus whatever he spent on alcohol for himself and weed for him and Mum. Things got even tighter when he started turning up at building jobs drunk at 9 o’clock in the morning and getting sent home. Eventually, when he stopped working altogether, he would sit around in the park all day, drinking with the other alcoholics who went there to while away their jobless hours.

Then, one day, Dan’s kids simply disappeared. I didn’t know what had happened to them: one minute they were there, teasing or tolerating me; the next minute they had gone. It wasn’t until much later that I found out they had been taken into care. Apparently, after moving on from using me as a decoy for their shoplifting exploits, the two boys had begun to get involved in more serious forms of petty crime. Then one of my stepsisters got an infection and was taken to hospital, where she was flagged up as ‘at risk’.

There were lots of things that didn’t make sense to me at that time – and there are many things that still don’t. But although I might not have understood what being taken into care meant, it would have been better if someone had given me some kind of explanation rather than none at all. As it was, the sudden, mystifying disappearance of my four stepsiblings was just one more of the many incidents that occurred during my young life that made me feel anxious and insecure.

Fortunately – perhaps – I always managed to escape the attention of social services as a child. I think there were two reasons for that: because Mum always kept me away from hospitals and because I was always clean and reasonably well dressed in clothes that were shabby but appropriate for my age. The reason for the first explanation was that Mum had been in care herself as a child and didn’t want me to experience whatever it was that had happened to her. The reason for the second seems to have been that as long as I wasn’t dirty, obviously malnourished or underweight, the social workers who never quite became involved in my childhood assumed I was being adequately looked after.

You can’t really blame the social workers for being fooled and for just scratching the surface. They must have seen lots of children who were more obviously at risk and more in need of their attention. And I think, particularly as I got older, they sympathised with Mum for having to cope with such an exhaustingly difficult child.

Eventually, and inevitably, the drink consumed Dan and he and Mum split up. When he moved out of the house with the muddy bathroom floor, I moved into the small bedroom in the attic, although, as it didn’t have a bed, I actually slept with Mum in her room. Then, after a while, Mum rented out the third bedroom to a series of lodgers, who seemed to come and go without incident, providing Mum with a small income for the minimum amount of hassle.

It was the first time it had been just Mum and me, but she was often too busy doing whatever it was she did to have time to bother with me. And as I hated being on my own, I was more or less forced into trying to make friends with some of the local kids. The problem was, even though I had started school by that time, I had absolutely no idea how to go about it. The way I had been brought up until then was almost feral: as long as I didn’t cause Mum any trouble, I was pretty much left to do whatever I wanted. Now, all I really wanted was to have a friend. But it’s hard to make friends when you don’t have a clue how to socialise.