скачать книгу бесплатно

I think of the mums in the school playground, of how the news will spread in hushed tones. I think of how they will fuss around Matt, eyes full of pity, of how they will never understand what I have done. I think of how he will have to excuse me, talk of grief, and how they will say that six years of grief is excessive.

And I know that they are right.

I think of Molly’s pink sandwich box, of routine, of her tastes, her quirks. I think of Matt struggling to find clean uniform, to dress, to juggle his work and his Molly. I know that he will be late for work if he waits for her to be clapped into school from the playground.

My thoughts are confused, jumbled, whirling.

I can still hear her sobbing.

I hope that Matt keeps her from school today, just today. He will need to go in to see the Headmistress, or telephone her, or both. The teachers will have to be told what an evil mother I am, of how I have abandoned my daughter and run away to a foreign country with my only son. But I know that any words exchanged will be missing the purpose, the point, that they will never fully understand why. I know, I appreciate, that people will be quick to judge me. I would hate me too. But, still, leaving my Molly, leaving my beautiful girl is dissolving any remnants of my remaining heart.

I think of her.

And then, suddenly, I am missing her, too much.

My sobbing vibrates through my body; it causes me to snort snot from my nose. My sobbing causes tears to stream.

and my shoulders shudder.

~shud – der.

~shud – der.

~shud – der.

beyond control.

I am out of control.

I pull my large shawl tighter around my shoulders. I bring the two ends together, up to my face, again. I bring the smooth material onto my face, until it covers my eyes, my nose, my being.

I breathe into my shawl.

I wonder if my Lord is laughing at me.

She wakes me.

‘Would you like any food or drink?’

I forget; for a moment, I am unsure where I am.

‘Would you like any food or drink?’ she repeats.

I look at her trolley. I see tiny bottles in a drawer.

‘Two whiskies, please,’ I say.

‘Ice?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘A mixer?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Anything else?’

I look to Christopher, he is absorbing the film; I wonder if he is reading lips, if I should buy him a headset. He seems to be on another planet, not really with me today, an outline.

‘Do you want a coke?’ I ask him.

Christopher looks at me then shakes his head.

‘Nothing else,’ I turn, I tell her.

‘Sorry?’ She is confused.

‘Nothing else,’ I repeat, louder, almost a shout. She nods, takes the drinks from the metal drawer; she does not question me any further.

‘That’ll be five pounds.’ I hand her Matt’s money, as she pulls down the table clipped onto the chair in front and places the drinks before me.

The whisky burns my throat but at least I feel something.

I stare out through the oval window, watching, waiting.

I see the sea, the deep blue sea.

The seatbelt sign goes on.

within minutes the click.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick – ing.

of metal is heard.

‘Cabin crew, ten minutes till landing,’ he says but we all hear.

And then, the plane is descending, rocking, bowing, dipping, shaking, swaying.

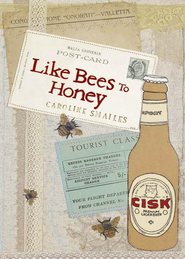

And then, I see Malta.

I see my Malta.

The island looks so tiny. I look through the small oval window. I see white, grey, green, blue. The natural colours dance before my eyes, they swirl and twirl and blend.

And as the plane dips, the colours form into outlines, then buildings, looking as if they have been carved into rock, into a mountain that never was. A labyrinth of underground, on ground, overground secrets have formed and twisted into an island that breathes dust. An island surrounded in, protected by a rich and powerful blue. I know that there is so much more than the tourist eye can see.

Quickly, the plane bows to my country, the honeypot of the Mediterranean.

And then, the wheels hit tarmac.

Mer

ba.

~welcome.

I am home.

Tlieta (#ulink_873b9344-33f4-5057-9119-5eb52dd47d93)

~three

Malta’s top 5: About Malta

* 3. Location

The Republic of Malta is a small, heavily peopled, island nation. Situated in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, south of Sicily and north of Tunisia, the islands benefit from the sunny Mediterranean climate.

I was born Maltese, in 1971, into a family that had been united through ages, through generations. Malta had first crumbled under the sun, then under siege, bombardment, invasion and yet each time it grew stronger. The dust, the ashes, it all formed into the labyrinths, secret passages that connect, divide, protect. The islanders have resilience, a determination, an acceptance of sorts. It is said that if you have been stripped to nothing, when you mend you alter, your aura changes, your purpose becomes clear.

My mother once told me, ‘In-nies ji

u Malta biex ifiequ.’

~people come to Malta to heal.

I left. I do not know what that means.

In Malta, my people speak the language Malti.

~Maltese.

We have a Semitic tongue that developed from the language spoken during Arabic invasion and occupation. Later came French-speaking Normans, the Knights of St John with their Italian and Latin, then British occupation. And so Malti became a combination of all the languages that drove through the island, of all those who came and left. It was born a rich, a breathing tongue, one that voiced our history, our invasions, our identity. When Malta later gained independence, both English and Maltese tongues were offered official status and Malti became the national language of my island, of Malta. It is known that my people can speak with one tongue, with two tongues, some speak with three or even four.

I was born into the home that was shared by my parents, by my grandparents, by my sisters and by my oldest aunt. It was the way, then. Our family was sealed, a unit that leaked noise, anger, laughter, excitement, wild gesturing with arms and hands.

There were no quiet moments. We liked it that way.

I was the third, the youngest daughter to be honoured upon Joseph and Melita. I was the favoured daughter of Melita. She called me qalbi.

~my heart.

My mother used to tell all that I was a kind, a loving, a quick-witted child. She would describe how my eyes carried a mischievous sparkle that warmed her. When I was a child, I could do no wrong.

But from an early age my feet would shuffle. I wanted to know more.

My mother would tell me that from the moment I could I would toddle out of the front door and down the steep slope that led to the harbour. My mother would tell me about frantic searches and screaming relatives dashing around the city. My mother would say that soon they learned to run to the harbour, that I would always be found standing on the same bench, waving at the boats.

And as I grew, my fascination with the atlas, the globe, the sphere, with the wide spaces and exotic names, grew too. No one could tell me of life off the island, no one had ever travelled to the distant, the bizarre-sounding shores.

I was restless to roam.

I longed for further than my island could give.

And so, as soon as an opportunity arose, I asked.

I asked my father if I could be educated away from the island, in England. Eventually, because I drilled and drained, my father agreed that I would travel, that I would be educated in the UK, but then I would return and marry a Maltese boy. I promised my father and then my mother that I would return. I promised them that they could choose my partner, I would agree to anything, to everything.

I promised.

My mother wept for twenty-eight nights.

One month before my nineteenth birthday, I flew to Manchester airport, and then climbed into a taxi to Liverpool University.

Four days later, I had found Matt.

I can, without any hesitation, avow that within four days on English soil I had met the man whom I was convinced I would spend the rest of my life in love with. Within four days, I knew that I would not keep my pact with my father, with my mother and that in doing so, I would break my mother’s heart.

As I was falling into Matt, my mother wrote to me. She said that when I left the island that ‘naqta’ qalbi’.

~I cut my heart, I lost hope.

She knew.

It was as if she could always see into my spirit and then into my mind. My mother gave up hope because she knew, just knew, that when I fell it would be totally, all or nothing. And so when I left Malta, my mother lost hope and now I realise that without hope, there is nothing.

I lost my virginity to Matt. I lost my family too.

I remember.

‘You make me lovesick,’ Matt said; he turned his naked back, away.

‘Is that bad?’ My fingers brushed his shoulder.

‘My heart is sick,’ he spoke and his shoulders began to quiver.

‘I don’t understand. What have I done?’ I feared the end of us. I remember that Matt turned to face me. We were squashed into a single bed, his student room, naked skin on skin.

I had known him for five days.

His fingers, his face, were covered in my scent.

I remember.