Полная версия:

The Kitchen Diaries II

Nigel Slater is the author of a collection of bestselling books and presenter of BBC I’s Simple Cooking. He has been food columnist for the Observer for twenty years. His books include the classics Appetite and The Kitchen Diaries and the critically acclaimed two-volume Tender. His award-winning memoir Toast – the story of a boy’s hunger won six major awards and is now a BBC film starring Helena Bonham Carter and Freddie Highmore. His writing has won the National Book Award, the Glenfiddich Trophy, the André Simon Memorial Prize and the British Biography of the Year. He was the winner of a Guild of Food Writers’ Award for his BBC I series Simple Suppers.

Also by Nigel Slater

Tender Volumes I and II

Eating for England

The Kitchen Diaries

Toast – the story of a boy’s hunger

Thirst

Appetite

Nigel Slater’s Real Food

Real Cooking

The 30-Minute Cook

Real Fast Food

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

A few notes on television

A few words of introduction

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

List of recipes by month

Just one more…

Copyright

About the Publisher

For James Thompson

Acknowledgements

Thank you, as always, to Louise Haines, my editor for over twenty years, for your endless encouragement, guidance and patience. Without you there would be no book.

To Jonathan Lovekin for taking beautiful pictures of so much I have cooked over the years. Thanks, Jonnie. I am grateful to Harry Borden for kindly allowing my publishers to use his thoughtful portrait of me.

To James Thompson, producer, kitchen genius and confidant. He who holds it all together. James, thank you for everything, but especially for your sure hand with the recipes, guiding their journey from diary to table, published page and television screen. For your inspiration, enthusiasm, hard work and friendship, I can never thank you enough.

To my literary agent Araminta Whitley and my television agent Rosemary Scoular, to Harry Mann, Sophie Hughes, Wendy Millyard and everyone at LAW, United Agents, Breckman and Company and Mishcon de Reya for dealing with all the really important stuff that I don’t understand.

To everyone at Fourth Estate, especially Victoria Barnsley, Michelle Kane, Georgia Mason and Olly Rowse. To David Pearson for helping to make this second volume of the diaries so beautiful and, as always, my thanks to Jane Middleton and Annie Lee for their eagle eyes and endless patience.

To everyone at the Observer, especially the wonderful Allan Jenkins, Ruaridh Nicoll, Martin Love, Gareth Grundy and John Mulholland. To Leah, Debbie, Helen and Caroline. And to Sarah Randell and Helena Lang. Thank you for your continued support.

To William, Sean and Mark and everyone at Fullers for all your hard work on the kitchen and to Steve Owens and everyone at Benchmark.

To Katie Findlay for helping to keep the garden in great shape; to Rob Watson at Ph9 for looking after www.nigelslater.com; to Dalton Wong and everyone at twentytwotraining for their endless encouragement and support and to Tim and Asako d’Offay and Takahiro Yagi for their wisdom and kindness.

And thank you to all the bookshops and those who work in them for their continued enthusiasm. And to everyone who enters their local booksellers and discovers the magic that lies on those creaking shelves and gets to know that there is nothing so beautiful as the feel and smell of a book in the hand.

A few notes on television

I had no real intention to present a television series. I had enough on my plate with a long-running weekly newspaper column and my books, and, however much I enjoy watching ‘celebrity chefs’, had no wish to be part of that world. The idea of filming a cookery series was suggested to me by Jay Hunt, at the time controller of BBCI. She gently persuaded me that there was room for a series with calm and gentle presentation and understated and simple food.

Not only did the series turn out to be a success beyond our wildest dreams, I ended up rather enjoying myself, and as a result there have now been four of the ‘Simple’ series. I owe a huge debt to Jay and to Ian Blandford, to Alison Kirkham and Tom Edwards and of course to Danny Cohen. To the production team and everyone at BBC Bristol, especially Pete Lawrence, Simon Knight, Jen Fazey, Michelle Crowley, James Thompson and Gary Skipton. And to my awesome crew who have made the shows what they are: Richard Hill, Sarah Myland, Robbie Johnson, Conor Connolly, Cheryl Martin, Simon Kerfoot, Sheree Jewell, Sam Jones and Archie Thomas. And thank you to Rudi Thackeray and his team. A big shout out also to the guys at Kiss My Pixel and to Mark Adderley and Nadia Sawalha. Thank you all.

This book is not a traditional television ‘tie-in’ but versions of many of the recipes in Simple Suppers and Simple Cooking can be found between these pages. (Others are in The Kitchen Diaries volume I and Tender Volumes I and II.) Thank you to the millions of you who watch each programme, and send such heartwarming letters, emails and tweets. I cannot tell you how much the entire team appreciates it.

And to that vibrant, warm and encouraging community at Twitter @realnigelslater. You are a joy.

Nigel Slater, London, September 2012

www.nigelslater.com

Twitter @realnigelslater

www.4thestate.com

A few words of introduction

I cook. I have done so pretty much every day of my life since I was a teenager. Nothing flash or showstopping, just straightforward, everyday stuff. The kind of food you might like to come home to after a busy day. A few weekend recipes, some cakes and baking for fun, the odd pot of preserves or a feast for a celebration. But generally, just simple, understated food, something to be shared rather than looked at in wonder and awe.

Sharing recipes. It is what I do. A small thing, but something I have done for a while now. As a cookery writer, I find there is nothing so encouraging as the sight of one of my books, or one of my columns torn from the newspaper, that has quite clearly been used to cook from. A telltale splatter of olive oil, a swoosh of roasting juices, or a starburst of squashed berries on a page suddenly gives a point to what I do. Those splodges, along with kind emails, letters and tweets, give me a reason to continue doing what I have been doing for the past quarter of a century. Sharing ideas, tips, stories, observations. Or, to put it another way, having a conversation with others who like to eat.

That is why, I suppose, each book feels like a chat with another cook, albeit one-sided (though not as one-sided as you might imagine). It is a simple premise. I make something to eat, everyone, including myself, has a good time, so I decide to share the recipe. To pass on that idea, and with it, hopefully, a good time, to others. For twenty years I have shared many of those ideas each week in my column in the Observer and in my books. They might also come dressed up a little nowadays, in the form of the television series, but it is still the same basic premise.

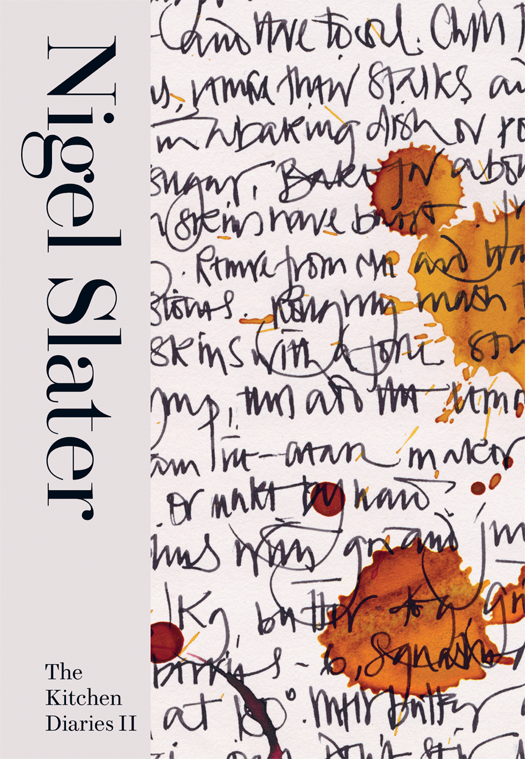

The diaries

For years now I have kept notebooks, with scribbled shopping lists and early drafts of recipes in them. These are not, I hasten to add, a set of exquisitely bound Kitchen Chronicles, but a scruffy hotchpotch, a salmagundi, of anything and everything I need to remember, from shopping lists and baking temperatures to whether it was two or three eggs that went into the cake. The books also contain the endless lists that I have written, almost obsessively, since childhood.

The notes, sometimes carefully annotated, sometimes not, vary from neat essays in longhand in black fountain pen to a series of almost illegible scribbles on any bit of paper that was handy at the time. The notebooks have recently been replaced, unromantically, by notes typed on an iPad. A decision I now rather regret. These notes form the basis of this second volume of The Kitchen Diaries. More than a diary, this is a collection of small kitchen celebrations, be it a casual, beer-fuelled supper of warm flatbreads with pieces of grilled lamb scattered with toasted pine kernels and bloodred pomegranate seeds or a quiet moment contemplating a bowl of soup and a loaf of bread. We can either treat food as nothing more than fuel or relish its every quality. We can think of preparing it as something to get done as quickly and effortlessly as possible or as something to find pleasure in, something to enrich our everyday life, to have fun with.

I have always written about the minute details of cookery, the small pleasures that can make it enjoyable and worth our time. (The bigger picture, the science and politics of food, its nutrition, provenance and chemistry, I leave to others who can do it better.) What intrigues me about making something to eat is the intimate details, the small, human moments that make cooking interesting. Whilst I never forget that most cooking is about getting something on the table at the end of a working day, I see no reason why it can’t be something to celebrate. The craft of making something with our hands, something for ourselves and others.

Between the pages of this book there are those days, hours and moments spent in the kitchen that I enjoyed enough to make notes about. The dish of quinces baking in the oven on a winter’s day; a hastily assembled salad of chicken, fresh peas and their new shoots; a bowl of brilliant-orange sweet potato soup for a frosty evening; a steak tossed with chilli sauce and Chinese greens; little cakes of crab and fresh coriander to eat with a friend, straight from the frying pan. It is also a collection of jottings about kitchen kit, a shout-out to the pieces of equipment that have become old friends: the favourite knife for peeling vegetables, the wooden spatula or spoon that feels more comfortable in the hand than any other. The bits and pieces we gather together over the years for our kitchen tasks that have become a pleasure to use. Their place in my life, like the most comfortable trainers that have seen better days, or the pullover with holes in it that you can’t bear to get rid of, is something I felt needed celebrating. These small pieces of equipment are part of my kitchen life.

The recipes

I am not a chef and never have been. I am a home cook who writes about food. Not even a passionate cook (whatever one of those is), just a quietly enthusiastic and slightly greedy one. But, I like to think, a thoughtful one. Someone who cares about what they feed themselves and others, where the ingredients come from, when and why they are at their best, and how to use them to give everyone, including the cook, the most pleasure. Whilst a bit of cookery is simply magic (some of the food being produced by professional chefs at the moment is extraordinary, exciting and wonderful), most of it is essentially craft, a subject that holds great interest for me. The art of crafting something by hand – a sandwich even – for others to enjoy is something I can always find time for. Making a dish over and over again till it is how you want it, whether a loaf of bread or a pasta supper for friends, gives me a great deal of pleasure. As does making an economical one-off dish from the ‘bits in the fridge’.

I’m neither slapdash nor particularly pedantic in the kitchen (I haven’t much time for uptight foodies; they seem to have so little fun). Neither am I someone who tries to dictate how something should be done, and I am never happier than when a reader simply uses my recipe as an inspiration for their own. If we follow a recipe word for word we don’t really learn anything, we just end up with a finished dish. Fine, if that’s all you want. Does it really matter how you get somewhere? I don’t think it does. Short cuts are fine, rule breaking is fine. What matters is that the food we end up with is lick-the-plate delicious.

I have never held the idea that a recipe should merely be a set of instructions (if that is what you want, there is plenty of it out there). I want more. The cookbooks dearest to me are those where the author has been more generous, adding notes and observations from their own kitchen. I like more than just an author’s fingerprint on a recipe.

What can be of particular value is when a previous reader’s notes come alongside those of the author. In a secondhand bookshop opposite Kew Gardens, I once came across a baking book by a well-known cookery writer. There were notes pencilled in the margin, alterations and occasional exclamation marks. A chocolate cake got three stars, the author’s ‘Moist Fruit Cake’ had the terse note, ‘No it isn’t’, scribbled across it.

Encouraging as it is when I find a well-used copy of one of my books in the kitchen, I am just as happy when readers tell me my book spends as much time on the bedside table. (‘There are three of us in this marriage, Nigel,’ is a sentiment I have heard more than once.) A good cookbook should be a good read, too. And that is what I hope this book will be to you. Recipes, yes, but also a collection of notes, suggestions and tips (though never, ever instructions or diktats) that I would like to pass on to others. All I want to do is share a good time through the medium of a recipe.

Let us never forget that we are only making something to eat. And yet, it can be so much more than that too. So very much more.

A note on the chronology

The first volume of The Kitchen Diaries was a chronological record of what I had cooked and eaten over the course of a single year. This second volume is slightly different in that it is compiled from a collection of my notes taken over several years, so a piece dated June 3 or November 5 could be from one of two or even three years.

The specific dates are relevant because they give a clear and essential link between what I cook and the seasons, a way of eating that has long been dear to my heart, but also because of the structure they bring to the disparate and somewhat chaotic form in which the jottings in my kitchen diaries tend to appear.

January

JANUARY 1

A humble loaf and a soup of roots

The mistletoe – magical, pagan, sacred to Norsemen and the Druids – is still hanging over the low doorway to the kitchen. Part of the bough I dragged back from the market the Sunday before Christmas, my hands numb from the cold. Its leaves are dull now, the last few golden-white berries scattered over the stone floor. Like the holly in the hearth, its presence was a peace offering to the new kitchen that still awaits its work surface, cupboards, sink, taps.

There is an English mistletoe fair at the market in Tenbury Wells each Saturday throughout December. Vast, cloud-like bunches are cut from local cider-apple orchards and sold along with holly and skeins of ivy. Mine came from an oak tree in Hereford, though nowadays much of the folklore-laden evergreen arrives by less-than-romantic truck from northern France. It is only the mistletoe grown on oak that is imbued with magical powers.

Empty glasses are scattered around the room, perched on shelves and window ledges from where we toasted the new, albeit unfinished kitchen. And there is just enough Champagne left in a bottle in the fridge for me to celebrate, in secret, the first morning of the New Year.

This January 1st is no different from all the others, in that I will make soup and a loaf in what is now an annual ritual. Kneading is a good way to start the year. Tactile, peaceful, creative, there is something grounding about baking a loaf on New Year’s Day. We have baked bread since the New Stone Age.

There has been a decade of New Year’s loaves in this house: a simple white bun, its surface softened with a bloom of flour; a dimpled foccacia that left our fingers damp with olive oil; a less than successful baguette, as thin as a wand; a brown, seeded loaf we ate for days like fruit cake; a flatbread; a crispbread; and once a craggy cottage loaf, its top slid to one side like a drunk in a top hat. I forget the others.

This year’s bread is the simplest of them all, a single, hand-worked loaf of strong white flour and spelt – the ancient cousin of wheat that is currently enjoying a renaissance. (This is less considered than it sounds: they are simply the flours I happen to have left in the cupboard after making mince pies.) Modern spelt is a hybrid of the emmer wheat and goat grass grown since the Iron Age, and has found favour with those who consider modern, commercial wheat heavy on the gut. I like it for the faintly nutty quality it brings to the party.

Making a loaf is cooking at its most basic – a bag of flour and a pinch of salt, some warm water and something to make it rise (baking powder, yeast, a home-made leaven). Yet there is more to it than that. There is something therapeutic about kneading live, warm dough. We do it in order to make the dough softer and more elastic, but the feel of dough in the hand makes you consider yourself a craftsman of some sort, which of course you are. I often knead my bread dough every twenty minutes or so, rather than the customary twice. Each kneading only lasts for about a minute. I do it gently too, without bumping or slapping. I am not sure any good can come from treating our food like a punch-bag.

I will attempt to achieve the yeasty sourness I want by using a glass of cider in place of some of the usual water and will get the crust crisp by punching the oven up to almost its highest setting. I want a crackling crust that shatters over the table when you break it, and a soft wholemeal crumb within. A good plain loaf that smells slightly sour and faintly lactic, yeasty, with a subtle fruitiness to it – a quiet and humble loaf with which to start a new year.

A cider loaf

Makes one medium-sized round loaf that will keep for two days and is still good for toast after four.

wholemeal spelt flour: 250g

strong white bread flour: 250g

sea salt: a lightly heaped teaspoon

whole milk: 150ml

honey: a teaspoon

fresh yeast: 35g

dry cider: 250ml

Warm a large, wide mixing bowl (I pour in water from the kettle or hot tap, leave for a minute, then drain and dry). Weigh the flours into the bowl – there is no point in sifting – then stir in the salt. Warm the milk in a small saucepan. It should be no hotter than your little finger can stand. Stir in the honey until it dissolves. Cream the yeast with a teaspoon in a small bowl, slowly pouring in the warm milk and honey. When it is smooth and latte coloured, pour it on to the flours together with the cider and mix thoroughly. I use my hands, though the mixture can be sticky at this point, but a wooden spoon will work too. When the dough has formed a rough ball, tip it out on to a lightly oiled or floured surface. Knead gently for one minute by firmly but tenderly pushing and stretching the dough with the heel of your hand, turning it round and repeating. Lightly flour the bowl you mixed the dough in and place the kneaded dough in it. Cover with a clean, preferably warm cloth and leave in a warm, draught-free place for an hour. Close proximity to a radiator will do, though not actually on it, as will the back of an Aga, a shelf in the airing cupboard or indeed anywhere the yeast can work.

Remove the dough, scraping off any that has stuck to the bowl, and knead lightly for one minute. Return to the bowl, cover and replace in the warm for twenty-five to thirty minutes, until the dough has risen once again.

Set the oven at 240°C/Gas 9. Knead the dough once more, this time forming it into a ball, then place it on a floured baking sheet and dust it generously with flour. Cover with a cloth and keep warm for a further fifteen to twenty minutes.

Put the dough in the oven and bake for twenty-five minutes. If it is nut-brown and crisp, remove it from the oven, turn it upside down and tap the bottom. Does it sound hollow, like banging a drum? Then it is cooked. Cool on a wire rack.

A soup of bacon and celeriac

Celeriac has long been part of the European kitchen, most notably in celeriac remoulade – a classic accompaniment to thinly sliced meats (a few slivers of air-dried ham, a couple of gherkins and a mound of mustardy remoulade is often a winter lunch in our house). The knobbly, ivory root has taken longer to find friends in this country, and we still have no classic British recipe that exploits its clean, mineral qualities. I use it for cold-weather soups, setting it up with bacon, mustard and either thyme or rosemary. The result is deceptively creamy.

medium onions: 2

butter: a thick slice, about 25g

smoked bacon: 120g

celeriac: 800g (1 large root)

thyme: the leaves from 3 small sprigs

chicken or vegetable stock: 500ml

water: 1 litre

grain mustard: 4 teaspoons

parsley: a small bunch

Peel the onions and roughly chop them. Melt the butter in a large, heavy-based saucepan and add the onions. Let them cook for ten to fifteen minutes or so, till translucent. As they cook, cut the bacon into short strips or dice and add them to the pan. Leave over a moderate heat, stirring occasionally, till the bacon fat is pale gold and the onions are soft.

While the onions and bacon are cooking, peel and coarsely grate the celeriac. Stir it into the onions, add the thyme leaves and a little salt, then pour in the stock and water. Bring to the boil, lower the heat and cover with a lid. Leave to simmer for thirty minutes, then stir in the mustard. Chop the parsley and add it to the soup with a seasoning of salt and black pepper. Simmer for five minutes, then remove from the heat.

Remove half the soup and blitz in a blender or food processor till almost smooth. You may need to do this in several batches, so as not to overfill the blender jug. Return the liquidised soup to the remaining soup in the saucepan. You will probably find the result is creamy enough, but if you wish to add some cream, then this is the point at which to do it. Check the seasoning and serve.