Полная версия:

The Friendship: Wordsworth and Coleridge

ADAM SISMAN

Wordsworth and Coleridge: The Friendship

DEDICATION

To George Misiewicz

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

PART I: Strangers

1. Revolution

2. Reaction

3. Idealism

4. Sedition

PART II: Friends

5. Contact

6. Retreat

7. Communion

8. Collaboration

9. Separation

10. Amalgamation

PART III: Acquaintances

11. Subordination

12. Estrangement

P.S. IDEAS, INTERVIEWS & FEATURES …

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Q&A: ADAM SISMAN TALKS TO SARAH O’REILLY

LIFE AT A GLANCE

TOP TEN FAVOURITE BOOKS

A WRITING LIFE

ABOUT THE BOOK

FRIENDSHIP NEGLECTED BY ADAM SISMAN

READ ON

HAVE YOU READ?

FIND OUT MORE

APPENDIX: Coleridge’s Plan for The Recluse

PLATES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NOTES

PRAISE

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ILLUSTRATIONS

The street in Bristol where the Pantisocrats lived for most of 1795. Line drawing by Edmund New.

Racedown Lodge in Dorset, occupied by Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy from 1795 to 1797. Line drawing by Edmund New.

The Nether Stowey cottage, home of the Coleridge family from the end of 1796 until the middle of 1799. Line drawing by Edmund New, 1914.

Alfoxden Park, rented by William and Dorothy Wordsworth in 1797–98. Line drawing by Edmund New, 1914.

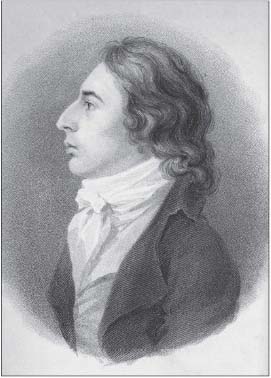

Wordsworth at the age of twenty-eight, by William Shuter. (Courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library)

Wordsworth aged thirty-six. Drawing by Henry Edridge. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Coleridge in 1798, by an unknown German artist. (Mrs Gardner)

Coleridge early in 1804, by James Northcote. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Silhouettes of Dorothy Wordsworth in 1806, and of Sara Hutchinson and Mary Wordsworth in 1827. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Miniatures of Sara Coleridge in 1809 (Getty Images) and of Annette Vallon, date unknown. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Hartley Coleridge, aged ten. (Frontispiece to Vol 1 of Hartley Coleridge’s Poems, 1851)

The Great Track over the top of the Quantocks, photographed in the 1930s. (Kit Houghton)

‘Alfoxton Park’ by Miss Sweeting, from a book of views published in the 1830s.

Greta Hall, illustrated in 1887. Postcard from Souvenir of the English Lakes. (Jeronime Palmer and Scott Ligertwood of Greta Hall, Keswick)

Landscape surrounding Greta Hall. Engraving from W. Westall’s original drawing. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Portrait of Robert Southey by James Sharpies, probably painted in 1795. (Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives)

Self-portrait by William Hazlitt, painted c.1802. (Maidstone Museum and Art Gallery, Kent/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Thomas Poole. (Frontispiece to Thomas Poole and his Friends by Mrs Henry Sandford, 1888)

Charles Lamb, after an original drawing by Robert Hancock, 1798. (From Reminiscences of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey by Joseph Cottle, 1847)

Joseph Cottle. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Leathes Water (Thirlmere), a mezzotint based on a pencil and wash drawing by John Constable made in 1806. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Grasmere in the early nineteenth century, by George Fennel Robson. (Dove Cottage, The Wordsworth Trust)

Ullswater. Engraving by Miller after Allom, c.1830. (Getty Images)

Three contemporary drawings by John Harden of Brathay Hall, not far from Grasmere. (Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Dove Cottage, photographed early in the twentieth century. (Getty Images)

Part-title portraits: Southey (page 1) and Wordsworth (page 121) after original drawings by Robert Hancock, 1796 and 1798 respectively. From Reminiscences of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey by Joseph Cottle (1847). Coleridge (page 327) by Peter Vandyke, 1795. courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

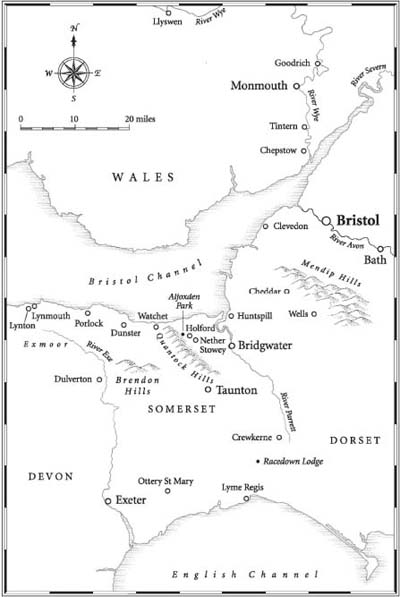

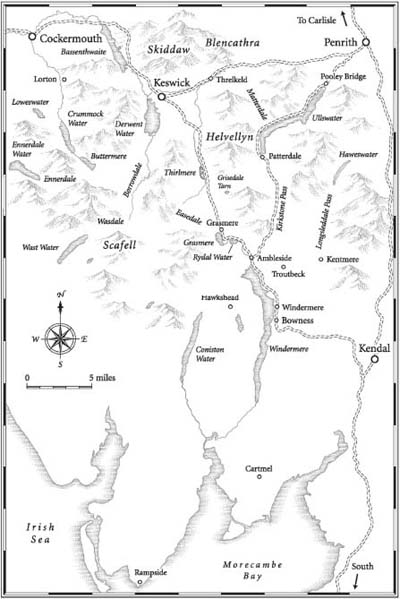

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

One June afternoon, more than two hundred years ago, a young man halted by a field-gate overlooking an isolated Dorset valley. His name was Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and he was twenty-four years old. He had walked forty miles since leaving his cottage in the Quantock Hills early the previous morning.

Beyond the gate, a cornfield stretched downhill towards the side of a substantial house, built in brick and partly covered by grey stucco render. In the kitchen garden two figures, a man and a woman, both about his own age, could be seen working; first one, then the other, paused and looked up towards where he stood.

The lane continued in a wide arc to the front of the house. Too impatient to take this long way round, Coleridge vaulted over the gate and bounded across the field towards the waiting figures, leaping through the corn. The two watchers, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy, retained a distinct memory of this sight almost half a century afterwards.1

Until this moment, Wordsworth and Coleridge had met only a handful of times. Now Coleridge planned to stay several days with his new friend – but they soon found that this was not enough, and he repeatedly postponed his departure. The two had much to say to each other, and after more than three weeks neither wanted to part; so it was rapidly arranged that the Wordsworths would move to the Quantocks. There the poets lived in close proximity, meeting almost daily, composing and developing their work together. This was an intensely creative time for them both. Under the constant stimulus of the other, each man would write some of his finest poetry. Ideas, themes and images would pass back and forth between them, one poem prompting a response from the other in exhilarating succession. And though this miraculously fertile period lasted only sixteen months, it was the seed-time of fruit that would ripen through the subsequent decade. Two years later their association would be renewed in the Lakes, where there would be a brief reprise of their poetic duet.

If Coleridge’s arrival on that June afternoon in 1797 was not the beginning of their acquaintance, it was the beginning of their intimacy. Previously they had exchanged ideas, expressed mutual regard, and offered friendly criticism. Now the relationship became much closer, one of dialogue and collaboration, of sharing plans and dreams.

The names of Wordsworth and Coleridge have been linked ever since. They have passed into legend as a pair, like Boswell and Johnson, or Lennon and McCartney. The myth-making began while they were still living, and has continued uninterrupted. The image of these two young geniuses, the progenitors of English Romanticism, roaming the Quantock Hills in an ecstasy of shared understanding and creative fulfilment, is irresistibly romantic. Their subsequent estrangement, quarrel, and superficial reconciliation complete a story as poignant as any love affair.

A shared ambition dominated the friendship between the two men. Both believed ardently that poetry could occupy a central place in the culture of the age. The visionary Coleridge dreamed of a great poem – perhaps greater than any yet written. It would encompass all human knowledge, and take twenty years to write. It would ensure the poet a place among the immortals; more important, it would hasten in the ‘blessed day’ of Mankind’s redemption, ‘the day fairer than this’: beginning where Milton left off.

Coleridge had scarcely sketched his utopian scheme before deciding that his friend was better suited to realise it. Wordsworth accepted the commission. For many years he struggled heroically to write this impossible poem, until at last he abandoned it, bitterly disappointed. The friendship that had been so productive at the beginning would end in failure.

‘Why do people have to like Wordsworth and hate Coleridge and vice versa?’ asked Edmund Blunden.2 The residual bitterness after their falling out has tended to distort subsequent interpretation of the relations between the poets. As a stimulating scholar who has written recently on relations between the two men has pointed out, understanding of them has been bedevilled by partisanship: ‘The practice of elevating one figure over the other has dominated Coleridge and Wordsworth biography for decades; to some extent because the very closeness of the two writers was later wrecked by savage disagreement. Interpreting one of them sympathetically almost inevitably means showing the other in a bad light.’3

My book is an attempt to escape from this biographical impasse, by concentrating on the friendship itself, at its most intense when both men were young and full of hope. Its core is the period of six and a half years between Coleridge’s exuberant arrival at Racedown Lodge and his sad departure for Malta. This is the story of two marvellously gifted young men, for whom anything seemed possible. At the outset, their friendship was beneficial to both, pushing each to higher aspirations. Overhanging all was their joint mission, to fulfil the hopes of a generation disappointed at the failure of the French Revolution: nothing less than a poem that would change the world.

PROLOGUE

‘How much the greatest event it is that ever happened in the world!’ exclaimed Charles James Fox on hearing of the fall of the Bastille, ‘and how much the best!’ The long struggle between Britain and France that began in 1793 has obscured the fact that most Britons (many of whom subsequently modified or concealed their enthusiasm) welcomed the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. Few then predicted how it would end. Some saw the changes transforming France as overdue, introducing the French to the liberties long enjoyed by Englishmen; others rather more excitedly as a precursor of the millennium, when the brotherhood of man would be established on earth. Half a lifetime afterwards, Robert Southey, though by then a staunch Tory, could still vividly recall the excitement of that time: ‘Few persons but those who lived in it can conceive or comprehend what the memory of the French Revolution was, nor what a visionary world seemed to open upon those who were just entering it. Old things seemed passing away, and nothing was dreamt of but the regeneration of the human race.’1

Even the Prime Minister William Pitt, later the most determined enemy of the French Republic, then looked forward to a reconstructed and free France as ‘one of the most brilliant powers of Europe’. France was arguably the most powerful nation in the world, certainly the centre of European culture and thought. Indeed, the events in France seemed likely to spread a beneficial influence everywhere. ‘The French, Sir, are not only asserting their own rights, but they are advancing the general liberties of mankind,’ declared John Cartwright, the Lincolnshire reformer. Like Cartwright, the nonconformist minister Richard Price was a veteran in the cause of liberty; according to him, the success of the American colonies in winning their independence was ‘one step ordained by providence’ towards the millennium. In a sermon preached to the London Revolution Society on 4 November 1789, Price gave thanks that he had lived to see this ‘eventful period’.* He predicted ‘a general amendment beginning in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priests giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience’.2

In almost every country of pre-Revolutionary Europe, princes ruled without check; their subjects suffered, unprotected by laws; perhaps worst of all, taxes were raised without consulting those who would have to pay them. France had been one of the most lamentable examples. In England, by contrast, the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 had limited the power of the monarchy, and established the rights of its subjects: liberty of conscience, the right to be governed by elected representatives, the freedom to make money and to hold property. Now, at last (a century after the British), the French were catching up. The rest of Europe would surely follow.

Such was the British view. There was a widespread complacency about the British way of doing things. How could the status quo be at fault when the nation was so rich? The struggles of the seventeenth century had been absorbed into the political culture, and were no longer threatening; on the contrary, they were a source of pride, evidence of superiority. However absurd this might seem to Americans, and indeed to peoples still subject to British rule, Britons were generally united in seeing their country as a lighthouse of liberty and prosperity on the edge of a benighted continent.

Even so, the unreformed House of Commons was hard to defend. Many MPs held sinecures granted by the Crown, which ensured that they would support the King’s government, right or wrong. Men went into Parliament expressly to obtain such posts. Elections were flagrantly corrupt; with only a small number of electors, who were easily bought, often by the simple expedient of providing free drink. Some seats had a mere handful of voters, and in one notorious example, none at all. In rural constituencies, a large proportion of the electorate owed their livelihoods to powerful landowners, who as a result virtually controlled elections. Such abuses, distressing in themselves, were (in the view of many) symptomatic of a deeper problem: as constituted, the House of Commons failed to represent the nation as a whole. Parliament was controlled by a self-perpetuating oligarchy, one that left significant sections of society without a voice. Pitt introduced a Bill to reform some of the more obvious abuses, only to have it thrown out by a suspicious House of Commons. Radicals called for bolder constitutional reforms, including secret ballots, regular elections, extension of the franchise, and restrictions on the power of the Crown to make appointments. Yet there was little popular pressure for change. A great many Britons agreed with Dr Johnson when he remarked that most schemes of political improvement were very laughable things.

The apparent success of the French Revolution encouraged British radicals. The dormant Society for Constitutional Information revived; a group of well-meaning young aristocrats designated themselves the Society of Friends of the People; and at the other end of the social scale a London shoemaker founded a Corresponding Society for the encouragement of constitutional discussion, which in time gave birth to similar societies around the country. Messages of solidarity were sent to France at each revolutionary development. The presses ran hot with political pamphlets. In dissenting circles, where many of the radicals were to be found, there was a strong hope that the laws barring from public office those who refused to conform to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England might be abolished, or at least relaxed. Dissenters in England were traditionally progressive; and increasingly discontented with an established order from which they were to a large extent excluded. Toleration was not enough; participation was what they wanted. Unitarians, who formed the intellectual elite of the dissenting movement, were rational Christians, preaching science, enlightenment and tolerance, and rejecting the mysticism of the Trinity. Not content with eventual salvation, they hoped for a better life on earth. For a Unitarian like the philosopher-chemist Joseph Priestley, the need for reform was self-evident; the system was clearly rotten.

Of course there were differences between these radicals: while some harked back to 1688, to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, others looked back further, to 1649, and the foundation of a republic. Another strand of radical opinion daringly discarded historical precedent, and asserted instead the natural and inalienable rights of man. Such differences, not always obvious at first, would become more distinct as the Revolution developed.

Even those John Bulls (and there were plenty of them) who believed that the British constitution could not be bettered had cause to welcome the news from France. For the century that preceded the Revolution, France had been Britain’s principal enemy in wartime and chief rival for empire. With a population almost three times that of Britain and a comparable overseas trade, plus revenues twenty-five times those of the new United States, France possessed resources unmatched by any country in the world. She had been contained only by heroic effort; she remained a dangerous Catholic power, a permanent menace to British security and Protestant freedoms. Now, perhaps, the long struggle was over. Until 1789, French strength had been concentrated in the hands of the French king. Within a matter of months, the French monarchy had been weakened; French despotism overthrown; the French threat seemingly diminished.

To the young, the tumultuous events in Paris – the gathering of the Estates-General, the tennis court oath, the formation of the National Assembly, the jostling crowds in the streets, the passionate rhetoric, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the sweeping reforms, the sudden collapse of the ancien régime – seemed irresistibly dramatic. The solemn ceremonies that took place throughout France promised an end to the abuses of the past. Above all, the storming of the Bastille, and the release of prisoners arbitrarily detained there, symbolised the liberation of the people as a whole. This inspiring moment was commemorated by the teenage Samuel Taylor Coleridge in one his earliest poems, ‘The Destruction of the Bastille’:

I see, I see! glad Liberty succeed With

every patriot* Virtue in her train!

For him, as for so many Britons, the French were simply following where Englishmen had gone before:

And still, as erst, let favour’d Britain be

First ever of the first and freest of the free!

* He was sixty-six, and died two years later.

* In the eighteenth century, a ‘patriot’ was one prepared to put duty to ones country above personal or sectional interest. During the Revolution, the term came to have a more specific meaning: one willing to defend the Republic against foreign invasion.

PART I Strangers

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!1

1 REVOLUTION

In the summer of 1790, William Wordsworth, then twenty years old and a commoner at St John’s College, Cambridge, together with Robert Jones, another Cambridge undergraduate, made a vacation walking tour across Europe. They set out from Calais on 14 July, the first anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. This was the climax of the week-long Fête de la Fédération, culminating in a tremendous spectacle in the capital, attended by 400,000 delegates from all over the country, and celebrated throughout France. The two undergraduates walked through towns and villages decorated with triumphal arcs and window-garlands; the whole nation seemed ‘mad with joy’.1 Wordsworth was a self-confessedly stiff young man, proud and prickly, but even he found it hard to resist the intoxicating mood:

…’twas a time when Europe was rejoiced,

France standing on the top of golden hours,

And human nature seeming born again.2

The thoroughfares of France were crowded with fédérés returning home from the festivities in Paris. Wordsworth and his companion fell in with a ‘merry crowd’ of these; after supper on a riverbank they danced around the table, hand in hand with the celebrants:

All hearts were open, every tongue was loud

With amity and glee. We bore a name

Honoured in France, the name of Englishmen,

And hospitably did they give us hail

As their forerunners in a glorious course;

And round and round the Board they danced again.3

At such a moment it was easy to assume that the Revolution had run its course, that a healthy France had purged itself, that monarch and people were united in a delightful new equilibrium. Had not the King sworn to uphold the decrees of the Assembly in front of a vast crowd at the Champ de Mars? Had he and his family not decamped from the magnificent Palace of Versailles to the Tuileries, in the very heart of Paris (albeit under duress)? Had he not appeared in public to greet the Mayor at the Hôtel de Ville, his hat adorned with the Revolutionary red-and-blue cockade?

‘It was a most interesting period to be in France,’ Wordsworth wrote to his sister from the shores of Lake Constance.4 But not that interesting: he and his friend Jones bypassed Paris, even though their route took them close to the capital, where all the most interesting events were happening. The Revolution was not their affair; they were headed for the Alps, then a sacred destination in the cult of the sublime. The young Englishmen joined in the Revolutionary festivities as guests, rather than participants. In his great autobiographical poem The Prelude, most of which was written a decade or more after the events described, Wordsworth admitted that

… I looked upon these things

As from a distance – heard, and saw, and felt,

Was touched, but with no intimate concern –5

(At this point a cautionary note is appropriate. On the one hand, The Prelude dramatises what Wordsworth called ‘spots in time’ – moments of special significance from his inner life. It is the principal source for the biography of his youth, particularly some obscure years of his young manhood for which the poem provides almost the only illumination. On the other hand, it cannot be wholly relied upon, and in at least some aspects is misleading. The emotional and psychological aspects of the poem may be more trustworthy than the merely factual and chronological – though perhaps not entirely so. In The Prelude, Wordsworth plots the growth of a poet’s mind’, from his infancy until he came into contact with Coleridge in his late twenties. But Wordsworth was writing in retrospect, trying to make sense of his past from the perspective of his mid-thirties. He had become a different man from the youth he was writing about. Not only was his memory fallible; there was a tendency in him, as in all of us, to manipulate the past in order to explain the present. Wordsworth’s biographers cannot avoid using The Prelude, but they need to do so cautiously, and to seek for confirmatory evidence elsewhere.)