Полная версия:

Lenin: A biography

LENIN

Life and Legacy

DMITRI VOLKOGONOV

Translated and edited by Harold Shukman

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1994

Copyright © Dmitri Volkogonov 1994

Translation copyright © Harold Shukman 1994

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007291649

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2012 ISBN 9780007392674

Version: 2016-03-21

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Map

List of Abbreviations

Chronological Table

Editor’s Preface

Introduction

1 Distant Sources

Genealogy

Vladimir and Alexander

The Forerunners

The Discovery of Marxism

Nadezhda Krupskaya

Inessa Armand

Financial Secrets

2 Master of the Order

Theorist of Revolution

The Phenomenon of Bolshevism

Lenin and the Mensheviks

The Paradox of Plekhanov

The Tragedy of Martov

3 The Scar of October

Democratic February

Parvus, Ganetsky and the ‘German Key’

Lenin and Kerensky

The July Rehearsal

October and the ‘Conspiracy of Equals’

Commissars and the Constituent Assembly

4 Priests of Terror

The Anatomy of Brest-Litovsk

White Raiments

Regicide

Fanya Kaplan’s Shot

The Guillotine of Terror

5 Lenin’s Entourage

The Most Capable Man in the Central Committee

The Man with Unlimited Power

The Bolshevik Tandem

The Party’s Favourite

The Leninist Politburo

6 The One-Dimensional Society

The Deceived Vanguard

Peasant Predators

The Tragedy of the Intelligentsia

Lenin and the Church

The Prophet of Comintern

7 The Mausoleum of Leninism

The Regime and the Illness

The Long Agony

The Mummy and the Embalming of Ideas

The Inheritance and the Heirs

Lenin as History

Postscript: Defeat in Victory

Keep Reading

Index

About the Author

Notes

About the Publisher

Map

Abbreviations

AMB Archives of the Ministry of Security AMBRF Archives of the Ministry of Security of the Russian Federation APRF Archives of the President of the Russian Federation ECCI Executive Committee of the Communist International GARF State Archives of the Russian Federation GPU State Political Administration KGB Committee of State Security NKGB People’s Commissariat of State Security NKVD People’s Commissariat of the Interior OGPU Combined State Political Administration PSS V.I. Lenin, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii (Complete Works), 5th edition, 55 vols., Moscow, 1970–85 RTsKhIDNI Russian Centre for the Preservation and Study of Recent Historical Documentation TsAKGB Central KGB Archives TsAMBRF Central Interior Ministry Archives of the Russian Federation TsAMO Central Archives of the Ministry of Defence TsGALI Central State Archives of Literature and Art TsGASA Central State Archives of the Soviet Army TsGoA Central State Special Archive TsGVIA Central State Military History Archives TsIK Central Executive Committee TsKhSD Centre for the Preservation of Contemporary Documentation VTsIK All-Russian Central Executive CommitteeChronological Table

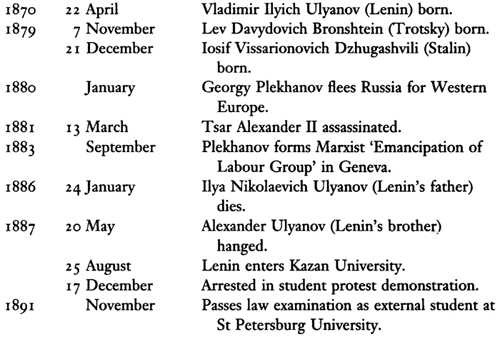

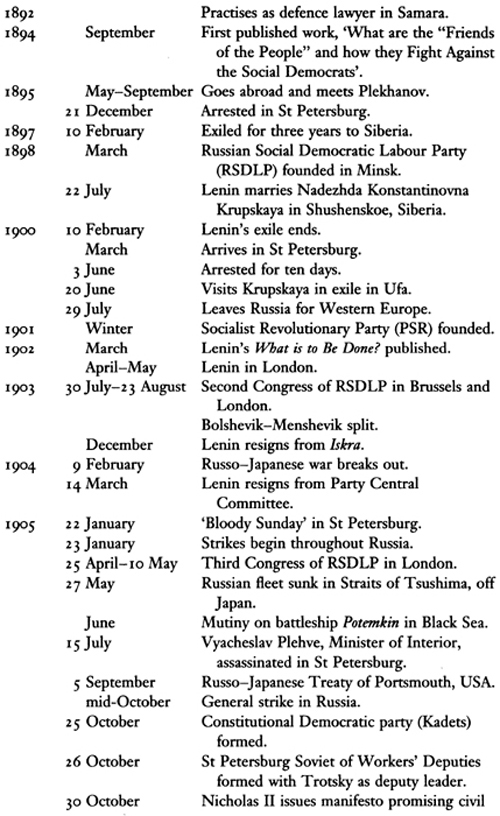

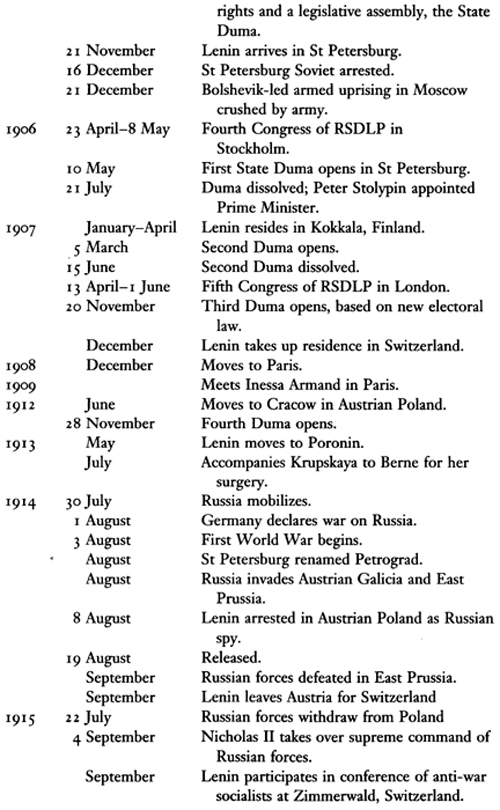

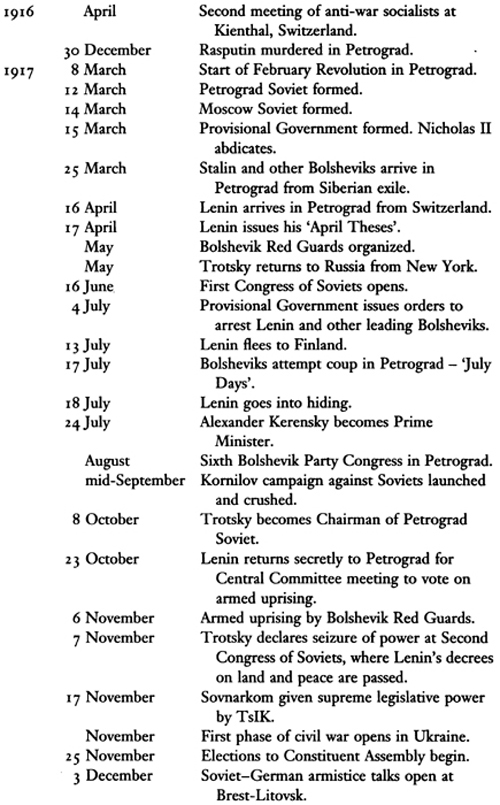

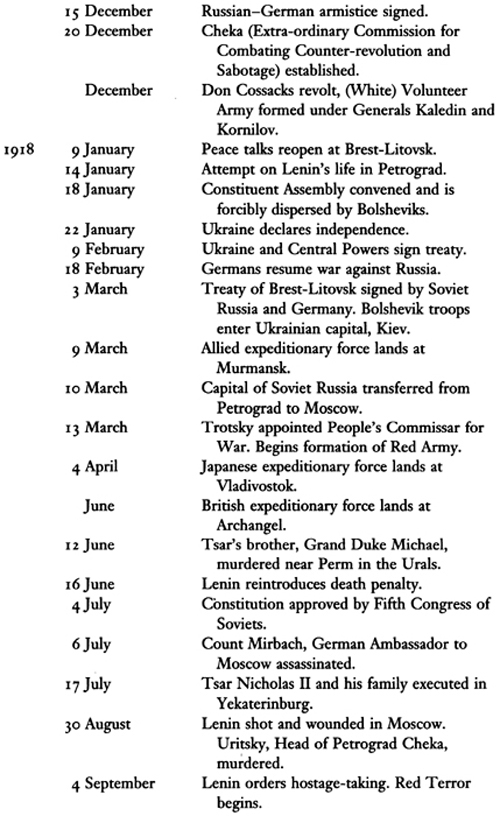

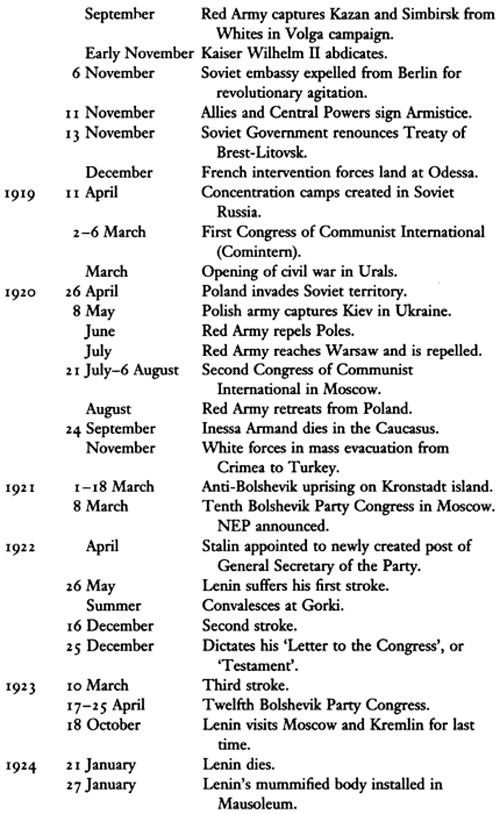

Until February 1918 dates in Russia conformed to the Julian or Old Style Calendar, which by the twentieth century was lagging thirteen days behind the Gregorian Western Calendar, or New Style. Thus, the February Revolution of 1917 took place in March according to the Western calendar and the Bolsheviks seized power on 25 October 1917, when in the West the date was 7 November. In the text we have used New Style dates, adding Old Style where any ambiguity might arise. In the following table, all dates are according to New Style.

Editor’s Preface

With the demise of the Soviet Union an era of Russian history was closed. It was an era that began in 1917 with the seizure of power by the Bolshevik Communist Party and ended with the disgrace and eviction of the same Party in August 1991, followed by the formal termination of the Soviet state itself at the end of the same year. From its inception to its end the Soviet state was identified with Lenin, whether alive or dead. Without him, it is generally accepted, there would have been no October revolution. Following the revolution, his name, his image, his words and his philosophy embellished, informed, exhorted and inspired generations of ordinary Soviet citizens, and especially those raised to positions of authority. He was made into an icon, a totem of ideological purity and guidance beyond questioning. All other Party leaders were found to be fallible in due course, many of the 1917 cohort in the great purge of 1936–38, and most famously Stalin in 1956 when Khrushchev debunked his ‘cult of personality’ at the Twentieth Party Congress. But Lenin remained untouched. As more and more topics of Soviet history were re-examined during Gorbachev’s enlightened leadership, and the Bolshevik old guard, exterminated in the 1930s, were rehabilitated, it became obvious that the spotlight must sooner or later fall on the last dark place on the stage – that occupied by Lenin.

A new reading of Lenin was made possible not only because Dmitri Volkogonov was granted access to the archives in the 1980s, but also, indeed chiefly, because Leninism itself had totally collapsed in the former Soviet Union. As the author of this book himself confesses, even after he had spent years collecting the incriminating evidence for his major study of Stalin, mostly written before 1985 and published in 1988, Lenin was the ‘last bastion’ in his mind to fall. Lenin has at last passed into history. No longer is he the prop of a powerful regime, the object of an ideology, or the central myth of a political culture. To engage in debate about Lenin and to assess his actions is no longer to challenge the legitimacy of an existing political system. Like him, it too has become history.

Books about Lenin have been coming out in the West almost from the moment the world first became aware of him in 1917. Even more abundantly, Soviet historians pumped out publications on allegedly every aspect of his life, and eye-witnesses of every degree added their own testimony in books with such titles as ‘They Knew Lenin’, ‘Lenin Knew Them’, ‘They Saw Lenin’, ‘Lenin Saw Them’, and so on, with variations on the theme effected by altering Lenin’s name: ‘They Knew Ilyich’, ‘Ilyich Knew Them’, etc., etc. Yet another book on Vladimir Ilyich Lenin therefore requires a word of justification.

Western books (including two by the undersigned) have largely been based on the published sources, many of them of Soviet origin. On the other hand, Soviet books from the outset have been apologist and ideological in content and purpose. From the end of the 1920s, when Stalin’s authority was complete, Soviet historians (like authors of creative literature, playwrights and film-makers) were strictly forbidden to write ‘objectively’, that is, from any other point of view than that laid down by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Now that the Central Committee has evaporated together with the Party, there are virtually no taboos on historical research left; Russian historians may if they wish differ in their assessment of any events they choose to analyse, but access to a widening pool of hitherto concealed data will at least ensure that their interpretations are based on the full facts. Areas which have been closed to them, and only partially known to Western scholars, and which have now been opened up in this book, include the complete documentation of Lenin’s genealogy, his financial operations – German involvement in the funding of Bolshevik activity during the First World War and Soviet funding of foreign Communist Parties after it – the nature of his friendship with Inessa Armand, and the effects of his illness on his political judgment, to mention a few.

The opening of the Party and other archives of Soviet history has been a gradual and intermittent process. Numerous efforts made to publish inventories and collections of documents have met with varied success, and so far it is fair to say the process is still at an early stage. Although with the failure of the attempted coup in August 1991 the Russian state took over from the Communist Party control of all the archival collections within its boundaries, the new state has barely formulated rules on the release of documents for publication, and the picture remains unclear. Nevertheless, even the minutes of the Politburo for the 1930s have been seen by Western and Russian scholars alike, and much valuable material is now appearing in two new journals devoted to the publication of extracts from the archives, Istoricheskii arkhiv and Istochnik, and a new series of miscellanies called ‘Unknown Russia’ (Neizvestnaya Rossiya), as well as an increasing amount of similar material in journals which have survived from the Soviet era. Subject to the rules and regulations of the Russian Archive Commission (Rosarkhiv), all the documents cited in this book can be seen at the various locations indicated. Documents from the Archives of the President of the Russian Federation (APRF) have been transferred from the Kremlin to the archives of the former Central Committee (RTsKhIDNI) and TsKhSD).

The first researcher to gain access to the most secret archives was Dmitri Volkogonov. As the Director of the Institute of Military History and a serving Colonel-General, he had for years collected material for his biography of Stalin. Its publication in 1988 made him a pariah among his fellow senior officers, whose patience with him finally ran out in June 1991, when the draft of a new history of the Second World War, edited under his aegis, was discussed at his Institute and condemned. Accused of blackening the name of the army, as well as that of the Communist Party and the Soviet state, and personally attacked by Minister of Defence Yazov, Volkogonov resigned. When the attempted coup followed two months later, Volkogonov was the government’s natural choice to supervise the control and declassification of the Party and State archives.

The author’s original Russian version of this book is considerably longer than this English rendition, and the two main principles that I applied in editing it deserve a mention. As a Russian historian suddenly able to write freely about this subject, Volkogonov ranged far beyond the history of his subject, particularly into philosophical reflection and into the backgrounds of topics which, while of special interest to his Russian readers, tended either to be excessively familiar to a Western reader, or to slow down the general chronological drift underlying the shifting narrative. I felt an English reader might become impatient at times for a return to the book’s central theme. My first rule was therefore to try to preserve as much as possible of the material – published as well as unpublished – either emanating from or pertaining to Lenin himself. My second principle was to preserve material demonstrating Volkogonov’s own thesis, namely that Stalin, his system and his successors, all derived directly from Lenin, his theories and practices.

Among the questions Russian historians have yet to confront is that of continuity. For many years, Western scholars have debated the extent to which the Soviet system inherited features of the tsarist empire. Some have argued that strong, centralized government by a self-appointed oligarchy was a Russian tradition, that a passive population, inclined towards collective rather than individualistic action and fed on myths of a special destiny and of rewards to come only in the distant future (if not only after death), was also characteristically Russian. Others, especially those closest in time to the events of 1917, have suggested that the liberal and democratic aspirations of the February 1917 revolution, when Nicholas II abdicated, had viable if shallow roots that would have become strong and stable, but for the intervention of the Bolsheviks.

Whatever their differences of emphasis, all schools, whether Western or Soviet, have agreed that the Bolshevik seizure of power, and the period of turmoil that immediately followed it, diverted the country irredeemably from any previously supposed path of development. The destruction of the liberal political intelligentsia by Lenin meant that the constitutional option was a dead letter; the decimation of the peasants’ political leadership left them exposed to the Bolsheviks’ violent exploitation of their economic potential; heavy-handed Bolshevik management of the trade unions prefigured their reduction to obedient servants of the regime; Lenin’s suppression of the free press set the scene for the censorship of information by the Communist Party that is erroneously taken to be the hallmark of Stalinism; Lenin’s immediate resort to the prison, the concentration camp, exile, the firing squad, hostages and blackmail, and his creation of an entire system of punishment to replace that of the tsars, set the new order on a path of violence and universal suspicion that was to become typical of twentieth-century tyrannies thereafter.

In the view of Dmitri Volkogonov, the question of whether or not Soviet history was a continuation in any sense of Russian history is of less importance than the question of whether Soviet history is itself a continuum. In this book, he shows that between Lenin and Stalin there was neither an ideological discontinuity, nor a difference of method. And, indeed, it is his contention that, while the methods employed by Stalin’s successors were much more moderate, they were just as motivated by the impulses of their legendary founder as their monstrous predecessor had been.

Among writers on the history of the Soviet Union – whether Westerners or Russian émigrés – it was not uncommon to trace events back and to seek a point at which ‘things might have gone differently’. Many have wondered whether, had Lenin not died so early in the life of the regime, the country might have developed along less militaristic and politically sterile lines. Perhaps the New Economic Policy, allowing peasants – more or less – to work for themselves, and permitting a degree of latitude in cultural life, would have continued and led to a more tolerant order of things. In the early years of glasnost this idea was widely debated by Russian as well as Western scholars. Among the latter were many who could not accept that any good could have come from Lenin and his creations, while some still retained a lingering doubt that such an intelligent man as Lenin could possibly have initiated and carried through the inhuman collectivization and the great terror of the 1930s. In Russia, as long as the Soviet state continued to exist, Lenin remained a virtually unblemished icon.

Dmitri Volkogonov has now demolished the icon, and he has firmly committed himself to the view that Russia’s only hope in 1917 lay in the liberal and social democratic coalition that emerged in the February revolution. He has, in other words, concluded that there was no salvation to be found in any of the policies practised by Lenin, and he has taken his account further to show how Lenin’s malign influence was imbibed by all subsequent Soviet leaders. Indeed, the Party leaders, he shows, quoted Lenin and referred to his teaching, not just when mouthing their pious platitudes for the populace, but even when they were closeted in the privacy of the Politburo. Having absorbed a philosophy that had failed almost before it was put into practice, it should have caused little surprise that the practitioners of Leninism in the modern age would ultimately share a similar fate.

Introduction

The massive steel door swung open and I was ushered into a large lobby, from which a similar reinforced door led to the Communist holy of holies, Lenin’s archives. The former Central Committee building on Staraya Square in central Moscow is a vast grey edifice the size of an entire city block. Along its endless corridors are the identical wood-panelled offices where the Party hierarchs once sat, dozens of meeting rooms of all sizes, a great reading room lined with catalogues and indexes to the Party’s meticulously preserved records. And deep in its basement, reminiscent of a nuclear bomb-shelter, on special shelves in special metal boxes, I was shown all the written traces to be found of the man still regarded by some as a genius, by others as the scourge of the century.

Despite the fact that there have been five editions of his collected works in Russian (the fourth of which was translated into many foreign languages), these are Lenin’s unpublished documents, numbering 3724 in all. Another 3000 or so were merely signed by him. Why were they hidden away? Could it be that his halo would have been tarnished by publishing, for instance, his instructions in November 1922 to punish Latvia and Estonia for supporting the Whites by such means as ‘catching them out’ with more and more evidence, by penetrating their borders ‘in hot pursuit’ and ‘then hanging 100–1000 of their officials and rich folk …’?1 Perhaps such documents were concealed because there was no one left who could explain them. As the Anarchist veteran Prince Kropotkin wrote to Lenin in December 1920, when the Bolsheviks had seized a large group of hostages whom they would ‘destroy mercilessly’ (in the words of Pravda) should an attempt be made on the life of any of the Soviet leaders: ‘Is there none among you to remind his comrades and to persuade them that such measures are a return to the worst times of the Middle Ages and the religious wars, and that they are not worthy of people who have undertaken to create the future society?’2 Lenin read the letter and marked it ‘For the archives.’

Of course, our view of Lenin has changed not only because we have found there is more than the stories that inspired us for decades. We began to doubt his infallibility above all because the ‘cause’, which he launched and for which millions paid with their lives, has suffered a major historical defeat. It is hard to write this. As a former Stalinist who has made the painful transition to a total rejection of Bolshevik totalitarianism, I confess that Leninism was the last bastion to fall in my mind. As I saw more and more closed Soviet archives, as well as the large Western collections at Harvard University and the Hoover Institution in California, Lenin’s profile altered in my estimation: gradually the creator and prophet was edged out by the Russian Jacobin. I realised that none of us knew Lenin; he had always stood before us in the death-mask of the earthly god he had never been.

After my books on Stalin and Trotsky,3 I set about the final part of the trilogy with the aim of rethinking Lenin. He had always been multi-faceted, but after his death his image was channelled into the single dimension of a saint, and the more we saw him as such, the more we distanced ourselves from the historical Lenin who was still, I think, the greatest revolutionary of the century.

The intellectual diet of Leninism was as compulsory for every Soviet citizen as the Koran is for an observing Muslim. On 1 January 1990 in the Soviet Union there were more than 653 million copies of Lenin’s writings in 125 languages – perhaps the only area of abundance achieved by Communist effort. Thus were millions of people educated in Soviet dogmatics, and we are still not fully aware how impoverished and absurd our idol-worship will look to the twenty-first century.

To write about Lenin is above all to express one’s view of Leninism. In 1926, two years after Lenin’s death, Stalin produced a collection called The Foundations of Leninism. Leninism, we were told, came down to making possible the revolutionary destruction of the old world and the creation on its ruins of a new and radiant civilization. How? By what means? By means of unlimited dictatorship. It was here that the original sin of Marxism in its Leninist version was committed – not that Marx, to give him his due, was much taken with the idea of dictatorship. Lenin, however, regarded it as Marxism’s chief contribution on the question of the state. In fact, according to him, the dictatorship of the proletariat constituted the basic content of the socialist revolution. His assertion that ‘only by struggle and war’ can the ‘great questions of humanity’ be resolved gave priority to the destructive tendency.4