скачать книгу бесплатно

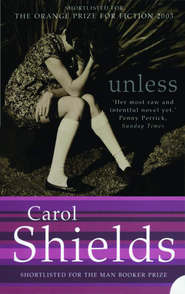

Unless

Carol Shields

Dazzling novel from Carol Shields, author of ‘The Stone Diaries’, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, and ‘Larry’s Party’, winner of the Orange Prize.‘Breathtaking…a masterpiece.’ Geoffrey Wansell, Daily MailReta Winters has a loving family, good friends, and growing success as a writer of light fiction. Then her eldest daughter suddenly withdraws from the world, abandoning university to sit on a street corner, wearing a sign that reads only ‘Goodness’. As Reta seeks the causes of her daughter’s retreat, her enquiry turns into an unflinching, often very funny meditation on society and where we find meaning and hope. ‘Unless’ is a dazzling and daring novel from the undisputed master of extraordinary fictions about so-called ‘ordinary’ lives.

UNLESS

CAROL SHIELDS

Dedication (#ulink_554fe787-6340-566f-8961-e1d891cda3e7)

For Ezra and Jay

Epigraph (#ulink_b7215fef-4e2b-5cc6-9752-9b6b266c45d2)

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.

GEORGE ELIOT

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u5eb3621e-bba8-559b-badc-b2fdcdeea69e)

Dedication (#ulink_2a691b70-80d6-5b56-9250-d6a5cab3bd41)

Epigraph

Here’s (#ud5af4b0d-e336-59d9-869e-d5b81778b22d)

Nearly (#u54294514-670c-5d0f-a9d9-e5a3fcf66ce9)

Once (#ue8a81440-b51a-5dad-91a5-71903eac3136)

Wherein (#ud253faac-97d2-5998-b3db-a1ba484eff5a)

Nevertheless (#u682f225d-ddd8-536b-9ebb-07a1a4882920)

So (#ue9df1e18-dd5c-5f1e-8fe1-fdca4c7e1b66)

Otherwise (#litres_trial_promo)

Instead (#litres_trial_promo)

Thus (#litres_trial_promo)

Yet (#litres_trial_promo)

Insofar As (#litres_trial_promo)

Thereof (#litres_trial_promo)

Every (#litres_trial_promo)

Regarding (#litres_trial_promo)

Hence (#litres_trial_promo)

Next (#litres_trial_promo)

Notwithstanding (#litres_trial_promo)

Thereupon (#litres_trial_promo)

Despite (#litres_trial_promo)

Throughout (#litres_trial_promo)

Following (#litres_trial_promo)

Hardly (#litres_trial_promo)

Since (#litres_trial_promo)

Only (#litres_trial_promo)

Unless (#litres_trial_promo)

Toward (#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever (#litres_trial_promo)

Any (#litres_trial_promo)

Whether (#litres_trial_promo)

Ever (#litres_trial_promo)

Whence (#litres_trial_promo)

Forthwith (#litres_trial_promo)

As (#litres_trial_promo)

Beginning With (#litres_trial_promo)

Already (#litres_trial_promo)

Hitherto (#litres_trial_promo)

Not Yet (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

The Work of Carol Shields (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Here’s (#ulink_79ce1d47-91f4-5808-9d1a-fa38045161e2)

IT HAPPENS THAT I am going through a period of great unhappiness and loss just now. All my life I’ve heard people speak of finding themselves in acute pain, bankrupt in spirit and body, but I’ve never understood what they meant. To lose. To have lost. I believed these visitations of darkness lasted only a few minutes or hours and that these saddened people, in between bouts, were occupied, as we all were, with the useful monotony of happiness. But happiness is not what I thought. Happiness is the lucky pane of glass you carry in your head. It takes all your cunning just to hang on to it, and once it’s smashed you have to move into a different sort of life.

In my new life—the summer of the year 2000—I am attempting to “count my blessings.” Everyone I know advises me to take up this repellent strategy, as though they really believe a dramatic loss can be replaced by the renewed appreciation of all one has been given. I have a husband, Tom, who loves me and is faithful to me and is very decent looking as well, tallish, thin, and losing his hair nicely. We live in a house with a paid-up mortgage, and our house is set in the prosperous rolling hills of Ontario, only an hour’s drive north of Toronto. Two of our three daughters, Natalie, fifteen, and Christine, sixteen, live at home. They are intelligent and lively and attractive and loving, though they too have shared in the loss, as has Tom.

And I have my writing.

“You have your writing!” friends say. A murmuring chorus: But you have your writing, Reta. No one is crude enough to suggest that my sorrow will eventually become material for my writing, but probably they think it.

And it’s true. There is a curious and faintly distasteful comfort, at the age of forty-three, forty-four in September, in contemplating what I have managed to write and publish during those impossibly childish and sunlit days before I understood the meaning of grief. “My Writing”: this is a very small poultice to hold up against my damaged self, but better, I have been persuaded, than no comfort at all.

It’s June, the first year of the new century, and here’s what I’ve written so far in my life. I’m not including my old schoolgirl sonnets from the seventies—Satin-slippered April, you glide through time / And lubricate spring days, de dum, de dum—and my dozen or so fawning book reviews from the early eighties. I am posting this list not on the screen but on my consciousness, a far safer computer tool and easier to access:

I. A translation and introduction to Danielle Westerman’s book of poetry, Isolation, April 1981, one month before our daughter Norah was born, a home birth naturally; a midwife; you could almost hear the guitars plinking in the background, except we did not feast on the placenta as some of our friends were doing at the time. My French came from my Québécoise mother, and my acquaintance with Danielle from the University of Toronto, where she taught French civilization in my student days. She was a poor teacher, hesitant and in awe, I think, of the tanned, healthy students sitting in her classroom, taking notes worshipfully and stretching their small suburban notion of what the word civilization might mean. She was already a recognized writer of kinetic, tough-corded prose, both beguiling and dangerous. Her manner was to take the reader by surprise. In the middle of a flattened rambling paragraph, deceived by warm stretches of reflection, you came upon hard cartilage.

I am a little uneasy about claiming Isolation as my own writing, but Dr. Westerman, doing one of her hurrying, over-the-head gestures, insisted that translation, especially of poetry, is a creative act. Writing and translating are convivial, she said, not oppositional, and not at all hierarchical. Of course, she would say that. My introduction to Isolation was certainly creative, though, since I had no idea what I was talking about.

I hauled it out recently and, while I read it, experienced the Burrowing of the Palpable Worm of Shame, as my friend Lynn Kelly calls it. Pretension is what I see now. The part about art transmuting the despair of life to the “merely frangible,” and poetry’s attempt to “repair the gap between ought and naught”—what on earth did I mean? Too much Derrida might be the problem. I was into all that pretty heavily in the early eighties.

2. After that came “The Brightness of a Star,” a short story that appeared in An Anthology of Young Ontario Voices (Pink Onion Press, 1985). It’s hard to believe that I qualified as “a young voice” in 1985, but, in fact, I was only twenty-nine, mother of Norah, aged four, her sister Christine, aged two, and about to give birth to Natalie—in a hospital this time. Three daughters, and not even thirty. “How did you find the time?” people used to chorus, and in that query I often registered a hint of blame: was I neglecting my darling sprogs for my writing career? Well, no. I never thought in terms of career. I dabbled in writing. It was my macramé, my knitting. Not long after, however, I did start to get serious and joined a local “writers’ workshop” for women, which met every second week, for two hours, where we drank coffee and had a good time and deeply appreciated each other’s company, and that led to:

3. “Icon,” a short story, rather Jamesian, 1986. Gwen Reidman, the only published author in the workshop group, was our leader. The Glenmar Collective (an acronym of our first names—not very original) was what we called ourselves. One day Gwen said, moving a muffin to her mouth, that she was touched by the “austerity” of my short story—which was based, but only roughly, on my response to the Russian icon show at the Art Gallery of Ontario. My fictional piece was a case of art “embracing/repudiating art,” as Gwen put it, and then she reminded us of the famous “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer” and the whole aesthetic of art begetting art, art worshipping art, which I no longer believe in, by the way. Either you do or you don’t. The seven of us, Gwen, Lorna, Emma Allen, Nan, Marcella, Annette, and I (my name is Reta Winters—pronounced Ree-tah) self-published our pieces in a volume titled Incursions and Interruptions, throwing in fifty dollars each for the printing bill. The five hundred copies sold quickly in the local bookstores, mostly to our friends and families. Publishing was cheap, we discovered. What a surprise. We called ourselves the Stepping Stone Press, and in that name we expressed our mild embarrassment at the idea of self-publishing, but also the hope that we would step along to authentic publishing in the very near future. Except Gwen, of course, who was already there. And Emma, who was beginning to publish op-ed pieces in the Globe and Mail.

4. Alive (Random House, 1987), a translation of Pour Vivre, volume one of Danielle Westerman’s memoirs. I may appear to be claiming translation as an act of originality, but, as I have already said, it was Danielle, in her benign way, wrinkling her disorderly forehead, who had urged me to believe that the act of shuffling elegant French into readable and stable English is an aesthetic performance. The book was well received by the critics and even sold moderately well, a dense but popular book, offered without shame and nary a footnote. The translation itself was slammed in the Toronto Star (“clumsy”) by one Stanley Harold Howard, but Danielle Westerman said never mind, the man was un maquereau, which translates, crudely, as something between a pimp and a prick.

5. I then wrote a commissioned pamphlet for a series put out by a press calling itself Encyclopédie de l’art. The press produced tiny, hold-in-the-hand booklets, each devoted to a single art subject, covering everything from Braque to Calder to Klee to Mondrian to Villon. The editor in New York, operating out of a phone booth it seemed to me, and knowing nothing of my ignorance, had stumbled on my short story “Icon” and believed me to be an expert on the subject. He asked for three thousand words for a volume (volumette, really) to be called Russian Icons, published finally in 1989. It took me a whole year to do, what with Tom and the three girls, and the house and garden and meals and laundry and too much inwardness. They published my “text,” such a cold, jellied word, along with a series of coloured plates, in both English and French (I did the French as well) and paid me four hundred dollars. I learned all about the schools of Suzdal and Vladimir and what went on in Novgorod (a lot) and how images of saints made medieval people quake with fear. To my knowledge, the book was never reviewed, but I can read it today without shame. It is almost impossible to be pseudo when writing about innocent paintings that obey no rules of perspective and that are done on slabs of ordinary wood.

6. I lost a year after this, which I don’t understand, since all three girls had started school, though Natalie was only in morning kindergarten. I think I was too busy thinking about the business of being a writer, about being writerly and fretting over whether Tom’s ego was threatened and being in Danielle’s shadow, never mind Derrida, and needing my own writing space and turning thirty-five and feeling older than I’ve ever felt since. My age—thirty-five—shouted at me all the time, standing tall and wide in my head, and blocking access to what my life afforded. Thirty-five never sat down with its hands folded. Thirty-five had no composure. It was always humming mean, terse tunes on a piece of folded cellophane. (“I am composed,” said John Quincy Adams on his deathbed. How admirable and enviable and beyond belief; I loved him for this.)

This anguish of mine was unnecessary; Tom’s ego was unchallenged by my slender publications. He turned out not to be one of those men we were worried about in the seventies and eighties, who might shrivel in acknowledgment of his own insignificance. Ordinary was what he wanted, to be an ordinary man embedded in a family he loved. We put a skylight in the box room, bought a used office desk, installed a fax and a computer, and I sat down on my straight-from-a-catalogue Freedom Chair and translated Danielle Westerman’s immense Les femmes et le pouvoir, the English version published in 1992, volume two of her memoirs. In English the title was changed to Women Waiting, which only makes sense if you’ve read the book. (Women possess power, but it is power that has yet to be seized, ignited, and released, and so forth.) This time no one grumped about my translation. “Sparkling and full of ease,” the Globe said, and the New York Times went one better and called it “an achievement.”

“You are my true sister,” said Danielle Westerman at the time of publication. Ma vraie soeur. I hugged her back. Her craving for physical touch has not slackened even in her eighties, though nowadays it is mostly her doctor who touches her, or me with my weekly embrace, or the manicurist. Dr. Danielle Westerman is the only person I know who has her nails done twice a week, Tuesday and Saturday (just a touch-up), beautiful long nail beds, matching her long quizzing eyes.

7. I was giddy. All at once translation offers were arriving in the mail, but I kept thinking I could maybe write short stories, even though our Glenmar group was dwindling, what with Emma taking a job in Newfoundland, Annette getting her divorce, and Gwen moving to the States. The trouble was, I hated my short stories. I wanted to write about the overheard and the glimpsed, but this kind of evanescence sent me into whimsy mode, and although I believed whimsicality to be a strand of the human personality, I was embarrassed at what I was pumping into my new Apple computer, sitting there under the clean brightness of the skylight. Pernicious, precious, my moments of recognition. Ahah!—and then she realized; I was so fetching with my “Ellen was setting the table and she knew tonight would be different.” A little bug sat in my ear and buzzed: Who cares about Ellen and her woven place-mats and her hopes for the future?

I certainly didn’t care.

Because I had three kids, everyone said I should be writing kiddy lit, but I couldn’t find the voice. Kiddy lit screeched in my brain. Talking ducks and chuckling frogs. I wanted something sterner and more contained as a task, which is how I came to write Shakespeare and Flowers (San Francisco: Cyclone Press, 1994). The contract was negotiated before I wrote one word. Along came a little bundle of cash to start me off, with the rest promised on publication. I thought it was going to be a scholarly endeavour, but I ended up producing a wee “giftie” book. You could send this book to anyone on your list who was maidenly or semi-academic or whom you didn’t know very well. Shakespeare and Flowers was sold in the kind of outlets that stock greeting cards and stuffed bears. I simply scanned the canon and picked up references to, say, the eglantine (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) or the blackberry (Troilus and Cressida) and then I puffed out a little description of the flower, and conferenced on the phone (twice) with the illustrator in Berkeley, and threw in lots of Shakespearean quotes. A sweet little book, excellent slick paper, US$12.95. At sixty-eight pages it fits in a small mailer. Two hundred thousand copies, and still selling, though the royalty rate is scandalous. They’d like me to do something on Shakespeare and animals, and I just might.

8. Eros: Essays, by Danielle Westerman, translation by Reta Winters, hastily translated—everything was hasty in those days, everything still is—and published in 1995. Hugely successful, after a tiny advance. We put the dog in a kennel, and Tom and I and the girls took the first translation payment and went to France for a month, southern Burgundy, a village called La Roche-Vineuse, where Danielle had grown up, halfway between Cluny and Mâcon, red-tiled roofs set in the midst of rolling vineyards, incandescent air. Our rental house was built around a cobbled courtyard full of ancient roses and hydrangeas. “How old is this house?” we asked the neighbours, who invited us in for an aperitif. “Very old” was all we got. The stone walls were two feet thick. The three girls took tennis lessons at l’école d’été. Tom went hacking for trilobites, happy under the French sun, and I sat in a wicker chair in the flower-filled courtyard, shorts and halter and bare feet, a floppy straw hat on my head, reading novels day after day, and thinking: I want to write a novel. About something happening. About characters moving against a “there.” That was what I really wanted to do.

Looking back, I can scarcely believe in such innocence. I didn’t think about our girls growing older and leaving home and falling away from us. Norah had been a good, docile baby and then she became a good, obedient little girl. Now, at nineteen, she’s so brimming with goodness that she sits on a Toronto street corner, which has its own textual archaeology, though Norah probably doesn’t know about that. She sits beneath the lamppost where the poet Ed Lewinski hanged himself in 1955 and where Margherita Tolles burst out of the subway exit into the sunshine of her adopted country and decided to write a great play. Norah sits cross-legged with a begging bowl in her lap and asks nothing of the world. Nine-tenths of what she gathers she distributes at the end of the day to other street people. She wears a cardboard sign on her chest: a single word printed in black marker—GOODNESS.

I don’t know what that word really means, though words are my business. The Old English word wearth, I discovered the other day on the Internet, means outcast; the other English word, its twin, its cancellation, is worth—we know what that means and know to distrust it. It is the word wearth that Norah has swallowed. This is the place she’s claimed, a whole world constructed on stillness. An easy stance, says the condemning, grieving mother, easy to find and maintain, given enough practice. A sharper focus could be achieved by tossing in an astringent fluid, a peppery sauce, irony, rebellion, tattoos and pierced tongue and spiked purple hair, but no. Norah embodies invisibility and goodness, or at least she is on the path–so she said in our last conversation, which was eight weeks ago, the eleventh of April. She wore torn jeans that day and a rough plaid shawl that was almost certainly a car blanket. Her long pale hair was matted. She refused to look us in the eye, but she did blink in acknowledgement–I’m sure of it–when I handed her a sack of cheese sandwiches and Tom dropped a roll of twenty-dollar bills in her lap. Then she spoke, in her own voice, but emptied of connection. She could not come home. She was on the path to goodness. At that moment I, her mother, was more absent from myself than she; I felt that. She was steadfast. She could not be diverted. She could not “be” with us.

How did this part of the narrative happen? We know it didn’t rise out of the ordinary plot lines of a life story. An intelligent and beautiful girl from a loving family grows up in Orangetown, Ontario, her mother’s a writer, her father’s a doctor, and then she goes off the track. There’s nothing natural about her efflorescence of goodness. It’s abrupt and brutal. It’s killing us. What will really kill us, though, is the day we don’t find her sitting on her chosen square of pavement.

But I didn’t know any of this when I sat in that Burgundy garden dreaming about writing a novel. I thought I understood something of a novel’s architecture, the lovely slope of predicament, the tendrils of surface detail, the calculated curving upward into inevitability, yet allowing spells of incorrigibility, and then the ending, a corruption of cause and effect and the gathering together of all the characters into a framed operatic circle of consolation and ecstasy, backlit with fibre-optic gold, just for a moment on the second-to-last page, just for an atomic particle of time.

I had an idea for my novel, a seed, and nothing more. Two appealing characters had suggested themselves, a woman and a man, Alicia and Roman, who live in Wychwood, which is a city the size of Toronto, who clamour and romp and cling to the island that is their life’s predicament—they long for love, but selfishly strive for self-preservation. Roman is proud to be choleric in temperament. Alicia thinks of herself as being reflective, but her job as assistant editor on a fashion magazine keeps her too occupied to reflect.

9. And I had a title, My Thyme Is Up. It was a pun, of course, from an old family joke, and I meant to write a jokey novel. A light novel. A novel for summertime, a book to read while seated in an Ikea wicker chair with the sun falling on the pages as faintly and evenly as human breath. Naturally the novel would have a happy ending. I never doubted but that I could write this novel, and I did, in 1997—in a swoop, alone, during three dark winter months when the girls were away all day at school.

10. The Middle Years, the translation of volume three of Westerman’s memoirs, is coming out this fall. Volume three explores Westerman’s numerous love affairs with both men and women, and none of this will be shocking or even surprising to her readers. What is new is the suppleness and strength of her sentences. Always an artist of concision and selflessness, she has arrived in her old age at a gorgeous fluidity and expansion of phrase. My translation doesn’t begin to express what she has accomplished. The book is stark; it’s also sentimental; one balances and rescues the other, strangely enough. I can only imagine that those endless calcium pills Danielle chokes down every morning and the vitamin E and the emu oil capsules have fed directly into her vein of language so that what lands on the page is larger, more rapturous, more self- forgetful than anything she’s written before, and all of it sprouting short, swift digressions that pretend to be just careless asides, little swoons of surrender to her own experience, inviting us, her readers, to believe in the totality of her abandonment.

Either that or she’s gone senile to good effect, a grand loosening of language in her old age. The thought has more than once occurred to me.

Another thought has drifted by, silken as a breeze against a lattice. There’s something missing in these memoirs, or so I think in my solipsistic view. Danielle Westerman suffers, she feels the pangs of existential loneliness, the absence of sexual love, the treason of her own woman’s body. She has no partner, no one for whom she is the first person in the world order, no one to depend on as I do on Tom. She does not have a child, or any surviving blood connection for that matter, and perhaps it’s this that makes the memoirs themselves childlike. They go down like good milk, foaming, swirling in the glass.

II. I shouldn’t mention Book Number Eleven since it is not a fait accompli, but I will. I’m going to write a second novel, a sequel to My Thyme Is Up. Today is the day I intend to begin. The first sentence is already tapped into my computer: “Alicia was not as happy as she deserved to be.”

I have no idea what will happen in this book. It is a mere abstraction at the moment, something that’s popped out of the ground like the rounded snout of a crocus on a cold lawn. I’ve stumbled up against this idea in my clumsy manner, and now the urge to write it won’t go away. This will be a book about lost children, about goodness, and going home and being happy and trying to keep the poison of the printed page in perspective. I’m desperate to know how the story will turn out.

Nearly (#ulink_bc948f65-df9a-5538-a7cf-854cfb24bd85)

WE ARE MORE THAN halfway through the year 2000. Toward the beginning of August, Tom’s old friend Colin Glass came to dinner one night, driving out from Toronto. Over coffee he attempted to explain the theory of relativity to me.

I was the one who invited him to launch into the subject. Relativity is a piece of knowledge I’ve always longed to understand, a big piece, but the explainers tend to go too fast or else they skip over a step they assume their audience has already absorbed. Apparently, there was once a time when only one person in the world understood relativity (Einstein), then two people, then three or four, and now most of the high-school kids who take physics have at least an inkling, or so I’m told. How hard can it be? And it’s passed, according to Colin, from crazy speculation to confirmed fact, which makes it even more important to understand. I’ve tried, but my grasp feels tenuous. So, the speed of light is constant. Is that all?

Ordinarily, I love these long August evenings, the splash of amber light that falls on the white dining-room walls just before the separate shades of twilight take over. The medallion leaves that flutter their round ghost shadows. All day I’d listened to the white-throated sparrows in the woods behind our house; their song resembles the Canadian national anthem, at least the opening bars. Summer was dying, but in pieces. We’d be eating outside if it weren’t for the wasps. Good food, the company of a good friend, what more could anyone desire? But I kept thinking of Norah sitting on her square of pavement and holding up the piece of cardboard with the word GOODNESS, and then I lost track of what Colin was saying.

E=mc

. Energy equals mass times the speed of light, squared. The tidiness of the equation raised my immediate suspicion. How can mass—this solid oak dining table, for instance—have any connection with how fast light travels? They’re two different things. Colin, who is a physicist, was patient with my objections. He took the linen napkin from his lap and stretched it taut across the top of his coffee cup. Then he took a cherry from the fruit bowl and placed it on the napkin, creating a small dimple. He tipped the cup slightly so that the cherry rotated around the surface of the napkin. He spoke of energy and mass, but already I had lost a critical filament of the argument. I worried slightly about his coffee sloshing up onto the napkin and staining it, and thought how seldom in the last few years I had bothered with cloth napkins. Nobody, except maybe Danielle Westerman, does real napkins anymore; it was understood that modern professional women had better things to do with their time than launder linen.

By now I had forgotten completely what the cherry (more than four dollars a pound) represented and what the little dimple was supposed to be. Colin talked on and on, and Tom, who is a family physician and has a broad scientific background, seemed to be following; at least he was nodding his head appropriately. My mother-in-law, Lois, had politely excused herself and returned to her house next door; she would never miss the ten-o’clock news; her watching of the ten-o’clock news helps the country of Canada to go forward. Christine and Natalie had long since drifted from the table, and I could hear the buzz and burst of TV noises in the den.

Pet, our golden retriever, parked his shaggy self under the table, his whole dog body humming away against my foot. Sometimes, in his dreams, he groans and sometimes he chortles with happiness. I found myself thinking about Marietta, Colin’s wife, who had packed her bags a few months ago and moved to Calgary to be with another man. She claimed Colin was too wrapped up in his research and teaching to be a true partner. A beautiful woman with a neck like a plant stem, she hinted that there had been a collapse of passion in their marriage. She had left suddenly, coldly; he had been shocked; he had had no idea, he told us in the early days, that she had been unhappy all these years, but he found her diaries in a desk drawer and read them, sick with realization that a gulf of misunderstanding separated them.

Why would a woman leave such personal diaries behind? To punish, to hurt, of course. Colin, for the most part a decent, kind-hearted man, used to address her in a dry, admonitory way, as though she were a graduate student instead of his wife. “Don’t tell me this is processed cheese,” he asked her once when we were having dinner at their house. Another time: “This coffee is undrinkable.” He loved pleasure—he was that kind of man—and took it for granted and couldn’t help his little yelps of outrage when pleasure failed. You could call him an innocent in his expectations, almost naive on this particular August evening. It was as though he were alone in a vaulted chamber echoing with immensities, while Tom and I stood attendance just outside the door, catching the overflow, the odd glimpse of his skewed but calm brilliance. Even the little pockets under his eyes were phlegmatic. He was not a shallow person, but perhaps he suspected that we were. I had to stop myself interrupting with a joke. I often do this, I’m afraid: ask for an explanation and then drift off into my own thoughts.

How could he now be sitting at our table so calmly, toying with cherries and coffee cups and rolling the edge of his straw placemat, and pressing this heft of information on us? It was close to midnight; he had an hour’s drive ahead of him. What did the theory of relativity really matter to his ongoing life? Colin, with his small specs and trim moustache, was at ease with big ideas like relativity. As a theory, relativity worked, it held all sorts of important “concepts” together with its precision and elegance. Think of glue lavishly applied, he said helpfully about relativity; think of the power of the shrewd guess. Such a sweeping perspective had been visionary at the beginning, but had been assessed and reinforced, and it was, moreover, Colin was now insisting, useful. In the face of life’s uncertainties, relativity’s weight could be assumed and then set aside, part of the package of consciousness.

He finished awkwardly, sat back in his chair with his two long arms extended. “So!” That’s it, he seemed to say, or that’s as much as I can do to simplify and explain so brilliant an idea. He glanced at his watch, then sat back again, exhausted, pleased with himself. He wore a well-pressed cotton shirt with blue and yellow stripes, neatly tucked into his black jeans. He has no interest in clothes. This shirt must go back to his married days, chosen for him, ironed for him by Marietta herself and put on a hanger, perhaps a summer ago.

The theory of relativity would not bring Colin’s wife hurrying back to the old stone house on Oriole Parkway. It would not bring my daughter Norah home from the corner of Bathurst and Bloor, or the Promise Hostel where she beds at night. Tom and I followed her one day; we had to know how she managed, whether she was safe. The weather would be turning cold soon. How does she bear it? Cold concrete. Dirt. Uncombed hair.

“Would you say,” I asked Colin—I had not spoken for several minutes—“that the theory of relativity has reduced the weight of goodness and depravity in the world?”