Полная версия:

Secret of the Sands

SARA SHERIDAN

Secret of the Sands

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2011

Copyright © Sara Sheridan 2011

Sara Sheridan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9781847561992

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007352524

Version: 2014-07-08

Author’s note about language

I do not speak Arabic and in any case spelling Arabic words with English letters spawns a wide variety of possible combinations that were not standardised until well after Wellsted’s day. I copied Arabic words from contemporary manuscripts and hope that the resulting spelling does not prove too confusing for those whose knowledge of the language is greater than mine.

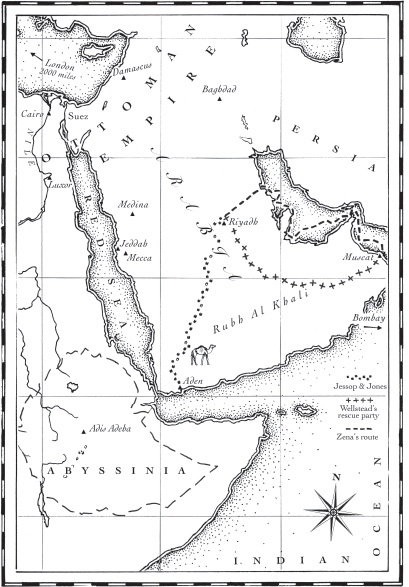

Map

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Author’s note about language

Map

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Part Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Part Three

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Epilogue

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

Historical Note

Questions for Reading Groups

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE

‘Thus in England, where law leaves men comparatively free, they are slaves to a grinding despotism of conventionalities, unknown in the land of tyrannical rule. This explains why many men, accustomed to live under despotic governments, feel fettered and enslaved in the so-called free countries.’

Sir Richard Francis Burton, 1821–1890

Great Arabian Explorer

Chapter One

Fifty miles inland from the coast of Abyssinia, Tuesday, 11 June 1833

It is dark when they come, at about an hour before dawn. Far away in London, pretty housemaids in Marylebone are setting the fires while the more dissolute rakes make their way home through deserted streets now devoid of the night’s sport. The whores are all abed now as are the Honourable Directors of the East India Company, each to a man concerned that the French, despite being routed, surely have it in mind to capture Bombay, Calcutta and Delhi and unfurl England’s grip on its ruby-encrusted prize. In short order, William Wilberforce, hero of The Cause, will rise habitually early despite his failing health, dress in a sober jacket with dark breeches and, discreetly and behind the scenes, preach the rights of these men and women from thousands of miles away. He has been doing so with success, in and out of Parliament, for the best part of fifty years and he will not have too much longer to wait. But here in the village that makes no difference now.

In the clearing surrounded by lush foliage, the silence is broken and the sleepy huts made of rushes and daub are already being ransacked. There is little anyone can do and it makes no odds whether the families rise fighting, iron daggers in hand, or wake slowly, sleepily, only half-conscious to the screams of their children. One or two of the quickest slip into the darkness, a jumble of long, flaying limbs and flashing eyes, young men abandoning their mothers and sisters, one child with the instincts of a seer, fleeing on instinct alone blindly into the dark jungle and away from the torches and the sparking embers of last night’s fire. A pitcher is knocked over in the panic and douses the rising flames, filling the cool, early morning air with a salty cloud of scorched goat curds that were meant to be breakfast.

It takes only seven minutes to capture almost everyone. The slavers are practised at this. They separate the elderly to one side (hardly worth the trouble to transport even as far as Zanzibar) and beat one old man who shouts so furiously and in such a babble that his own wife cannot fully understand him. There is always one would-be hero. He is usually a grandfather. The slaver known as Kasim consigns him to silence.

The broken body quietens the crowd. The villagers shift uneasily and the raiders turn to the task of sorting through the women. This is the most difficult job for mistakes are easily made with these dusky women in the darkness. Abyssinian slave girls are worth a great deal if they are beautiful. Sultans and emirs have been known to take an ebony slave or two to wive – a rich man’s harim is a place of no borders and should include every colour of skin, after all. White, of course, is the most enticing. Most men have never so much as seen white skin – all those who have agree it is strange and unearthly, the skin of a fearsome devil, a soul bleached to the colour of dry bones and shocking to the core, like a spectre. But still, on a woman, desirable enough.

In this village the women are as dark as bitter coffee and their young bodies are lithe. Kasim’s boyhood friend and business partner, Asaf Ibn Mohammed, eyes the pert titties as if they are liquorice. When he comes to Zena, Ibn Mohammed raises the hem of her winding cloth with the tip of his scimitar and glares at her ripe pudenda. He thinks only of the Marie Theresa dollars that this prize is worth shipped on to Muscat, and how easy she will be to sell. Then, dropping the skirt, he reaches out to check her teeth and nods to his fellow, the one with the ropes.

‘This one,’ he says in Arabic, his tawny eyes cold, the contours of his face caught in the flickering lamplight so it appears he is composed of nothing but long, thin lines. Paler and taller than Kasim, Ibn Mohammed has an elegant air and looks more like a scholar than a man of action. Today nothing has riled him – the raid is going entirely as he expects, so his temper, which often proves deadly, remains in check. ‘Yes, this one will do. Not as skinny as the others and she shows no fear.’

Zena, frozen and so afraid that she is scarcely able to breathe, pretends she cannot understand him. He seems so calm and cold, assured in his right to simply steal her away. Kasim nods silently in agreement though his black eyes sparkle – she can see he is enjoying the process of humiliating the villagers as they are assessed one by one. Something in him feeds off the uneasy atmosphere. The raid isn’t merely a living for this man. In the trade he has found his vocation.

I will run, she thinks. I will run. But her legs do not move. It is probably a blessing – the slavers do not deal kindly when they catch the ones who try to get away. You escape either very quickly or not at all. This is no time for Zena to show her spirit. As the guards pull her out of the line, she stumbles over the corpse of her uncle, the old man she has just watched Kasim murder with his bare hands. Zena does not look at the body. She tries to ignore the outrage that is rising in her belly. Silently, she lets them bind her along with some of the others and then, with the rising sun before them, the slavers drive their spoils, the pick of the village, away from their homes and families forever.

Chapter Two

The principal residence of Sir Charles Malcolm, Head of the Bombay Marine, India

The punkawallah has been on duty for over twelve hours and the wafting fan has slowed to a soporific movement that is having little effect on the soupy air.

‘Feeling better, Pottinger?’ Sir Charles enquires as he pours them each a drop of dry, ruby port from the Douro.

‘Oh yes, sir. The fever is gone. Had to be done, I expect,’ the young man assures his superior brightly, as if he had been serving at the wicket on the village cricket team. For new arrivals, a fever is practically mandatory, though by all accounts Pottinger had a particularly fierce bout and is fortunate to have survived.

‘Go on then, have a look,’ Sir Charles motions.

The captain crosses eagerly to the mahogany table and pores over the new charts of the Red Sea that arrived at the dock only a few hours before. The papers represent the first step in the Bombay Marine’s overall mission in the region, which is twofold. First, to find a way to link Europe to India inside a month by cutting out the African leg of the existing route. If that means developing the market for trade with the Arabs so much the better. Second, to ensure that recent British naval losses on the reefs of the tropical Arabian seas are never repeated. In the scramble for global dominance every scrap of advantage to be had over the French is vital and too many ships have gone down of late due to in adequate maps. For the East India Company these tactics have worked well elsewhere and it is gratifying to Sir Charles that more of the map is coloured pink every year and, in particular, that this victory is in no small measure due to the exploits of his men. It is for this reason that he briefs each of his officers personally at the beginning of their tour of duty. ‘Gives me the measure of them,’ he says.

Pottinger sees immediately that though the newly arrived drawings are detailed in places, there remain gaps. ‘When will our chaps complete it?’ he asks.

‘Another year, at least. And that is with both ships splitting the work. It’s hostile territory and the coastline is complex. We’ve sent a small exploratory party inland to the west of the Arabian Peninsula from the ship Palinurus. Information gathering, that kind of thing. It’s a start.’ Malcolm is glad that Pottinger is getting to grips with the issues. ‘The party comprises a lieutenant and a ship’s doctor, Lieutenant Jones and Doctor Jessop. They’ve gone in south of Mecca with a party of local guides and will travel as far as the camp of a Bedouin emir that we have paid for the privilege. The whole area is desert. The rendezvous is at Aden in four weeks.’

‘They sent in a doctor?’

‘An officer like any other.’ Sir Charles waves his hand blithely. Officers of the Bombay Marine are expected to turn their hand to anything. The corps prides itself on the flexibility of its men – a single officer can make a huge difference, in fact, many of the East India Company’s most startling successes have been instigated by a bright spark who has taken the initiative on the Company’s behalf. ‘Apparently, he was keen,’ Sir Charles says.

‘So, if we can secure Egypt,’ Pottinger muses, ‘we will still have to ferry everything across the land at Suez.’ He points at the most northerly port on the Red Sea.

In Sir Charles Malcolm’s experience, these discussions always come back to the same point on the map but it is good the lad has cottoned on so quickly. The thin strip of land in question lies between his territory and that of his brother, Pultney, who is Commander in Chief of the British Navy in the Mediterranean. Between them, the Malcolm brothers rule most of Britannia’s waves and keep an eye on the French for His Majesty. It is acknowledged that Sir Charles has the raw end of the deal. The Gulf is tribal and savage and even if they can oust the French from Egypt, Malcolm is all too aware how difficult it is to move substantial quantities of troops and supplies, to say nothing of trade goods, from one sea to another. There is no obvious place to build a railway to indulge in the relatively new science of steam locomotion. In any case, the land around Suez that is not desert is peppered with saltwater lakes – mixed terrain is, to use Sir Charles’ own parlance, the most tricky of all.

The Malcolm brothers, however, act as a team and by hook or by crook they will fix this problem somehow, so that not only will the sun never set on His Majesty’s empire, but His Majesty’s troops will move as smoothly as possible across it. If Hannibal can cross the Alps, Sir Charles Malcolm will be damned if he can’t get British men and goods across what is essentially a thin land bridge, whether he has to employ elephants to do the job or not.

Malcolm marks the chart carefully to show Pottinger what he’s hoping for.

‘Ooh, the French won’t like that,’ the youngster smiles.

Malcolm makes a sound like a furious camel and a gesture that clearly demonstrates that he couldn’t care less what the French would like. Some of Sir Charles Malcolm’s friends and acquaintances have not yet given up on England winning back her influence in French ports despite an almost four-hundred-year gap since the end of the Hundred Years War. Sir Charles Malcolm is no quitter nor are any of his ilk. He takes another sip of port.

Pottinger puts his finger on the dot that marks Suez. ‘A canal would be the easiest way … But the chart, sir, the chart is everything. We can’t go further without it.’

The boy is sharp. He’ll do.

At this juncture, Sir Charles notices that the punkawallah is lying prone and has dropped the red cord with which he should be operating the fan. The child has fallen fast asleep and, if Sir Charles is not mistaken, is dribbling over the Memsahib’s fancy new carpet.

‘Well, really,’ the Head of the Bombay Marine bellows, ‘no wonder it’s like a bally oven in here, and we are trying to think.’

He launches a pencil across the room. It hits its target admirably, striking the boy squarely on the forehead. The child jerks upright, mortified at his dereliction of duty and starts to babble, apologising frantically in Hindi. Then he recalls that it is an absolute rule that the house staff should remain silent at all times. Sir Charles, now somewhat pink in the cheeks, stops in his fury and laughs at the aghast expression on the boy’s face.

‘Go!’ he motions the child. ‘Away with you! Fetch another punkawallah, for heaven’s sake, or we’ll broil in here. It’s June, for God’s sake.’

The boy bows and disappears instantly as Pottinger pours more port into his glass and passes Sir Charles the decanter. ‘Thank you for showing me, sir,’ he says.

Sir Charles raises his glass. It is unusual for a commanding officer to bother, but Sir Charles always prefers to survey his resources personally. ‘Welcome to the Bombay Marine,’ he says. ‘A toast – to the very good health of His Majesty and, of course, our chaps in the field,’ he says as he reminds himself silently that the chaps in the field are getting there. Slow but sure.

Chapter Three

Rubh Al Khali on the way to the Bedouin encampment

In the desert it is so hot that it comes as a surprise that a human can breathe at all. At first, when he headed into what the Arabs call the Empty Quarter, with the intention of mapping the unknown, Dr Jessop did not expect to survive, but now lethargy has fallen upon him and he has ceased to worry about what the heat may or may not do. It has become clear, at any rate, both that breathing is possible and that there is no measure in moving from the shade of the acacia tree where the small caravan has halted. It is always hot in the desert, but June is one of the worst months. It is simply the way it has worked out.

‘Even in this bloody shade, you could bake a cat,’ he comments, dry mouthed.

He is a scientific man and a surgeon; in all probability he is right. Lieutenant Jones, his blonde hair plastered to his head with sweat, can do little more than gesture in agreement. He does not believe that the loose, Arabic outfit for which he swapped his uniform is any help at all with the heat, but he cannot quite form the words to communicate this or to ask if Jessop is of the same opinion. In any case, he has taken off the kaffiya headdress with its heavy ropes, for he could not bear them – the damn thing is heavier than a top hat and the cloth gets so hot in the sun that it burns the delicate skin at the back of his neck. Now it is after midday, and when the sun goes down they will start moving again. The Arabs have agreed to travel solely at night to accommodate the white men. They would not do so normally, but the infidels are unaccustomed to the conditions and if they die, the men will not be paid.

In the meantime, one of the bearers, a Dhofari, is making coffee. He grinds the beans and adds a fragrant pinch of cardamom to spice it. The Dhofaris carry spice pouches; their very bodies seem to secrete frankincense and their robes smell musky like powdered cumin. They bring a hint of Africa, a spice indeed, to the Arabian Peninsula. Amazingly, these men can work in the heat without breaking a sweat. Even now, the man’s brother is trying to milk one of the camels that Jessop bought in the market at Sur for the trip, but the beast, bare skin and bone, will not comply. It is a serious business. You cannot carry enough food and water in the desert, and what you can carry either spoils quickly or requires moisture to cook it. Camel’s milk is vital. The men have been hungry and thirsty for days and without enough camel’s milk to supplement supplies, the skins of water are running dangerously low. The Dhofari tethers the beast securely with a thick rope, hobbling the animal’s legs in the same fashion they do to stop the camels wandering off when the caravan breaks its journey and the men are sleeping. The beast nonchalantly chews on a sparse plant with tiny leaves growing in a bare patch of sweet grass and euphorbia, while the Dhofari guide disappears into his baggage. Jessop strains to see what he is doing. Quite apart from the prospect of fresh milk, which is enticing enough, these Arab customs are important. He is here to find out what is acceptable, how to trade with these people, how to supply British ships and protect them from attack. It is his job to understand this harsh country and to find out if it is possible for Britain to make a profit here. The doctor is looking forward to returning home to Northumberland and diverting society with his stories of the Ancient Sea and her Savages. He already has the title of his book planned, you see. And this is just the kind of thing, he is sure, that will entertain the chaps at home next winter.

As a vision of Northumberland – a hillside swathed in snow and puddles glassed over with chill sheets of ice – flashes across the doctor’s brain like a cool breeze, he reaches automatically for the coffee that is handed to him. ‘Thank you,’ he says. Shukran.

Jones only manages a nod though quickly the bitter taste revives him. He wishes he had not come to the desert. Aboard the Palinurus there was at least the prospect of a breeze. They will be back at the coast in perhaps ten days and will rendezvous with the ship a fortnight after that. This seems an interminable period to bear the baking, desiccated hellhole through which they are travelling, though the men surely will endure it – they are determined.

The Dhofari squats and sips alongside the white men. ‘Tonight we will have milk, in sh’allah,’ he says.

If Allah wills it.

‘We will reach the Bedu soon?’ Jones checks.

The man bristles. ‘Tomorrow, perhaps.’

The Bedouin encampment is the halfway mark – as far as they will venture this trip. Though the arrangement had been made for them and a price agreed, the timescale had been, of necessity, fuzzy. However, now they are embarked, the Bedu will be expecting their arrival, for news travels quickly in the desert – far more quickly, the white men are coming to realise, than in London where at least a fellow has a chance of keeping a secret. An adept guide can tell an enormous amount from a few blunt scratches in the sand. These men recognise one camel’s tracks from another, how many are in the party and who is injured or ill. The tribesmen have a keen memory for the precise pattern each camel makes on the shifting landscape – the beast’s hoofmarks and its individual gait. Out on the sands a mere line out of place tells them there is a foreigner riding a camel. While a desiccated turd robs an entire, long-gone caravan of all its secrets. They are like fortune tellers.

Jones is not interested in the native population and remains unimpressed by their tracking skills. The lieutenant has it in mind to find out more about transporting Arabian horses back to Europe – his own private concern rather than that of the Marine. Thoroughbreds are the only civilised international currency the Peninsula has to offer. Now they cannot send slaves home to London, that is, and it looks likely that the Empire will soon close its doors to human traffic besides and there will be no trade westwards either. Jones had hoped for jewels in Arabia. He had daydreamed of pearls as round as muscat grapes and plentiful as if on the vine, of emeralds big enough to fill a handmaiden’s belly button and diamonds bright and copious, like desert stars. His dreams have been quickly shattered. While there are occasional treasures, most of the people on the Peninsula are poor and, like everywhere else in the world, riches are hard to come by. A tenant farmer at home probably owns more in the way of material goods than the average emir. Jones is coming to accept there is little either His Majesty or himself is likely to profit from this expedition. No wonder the whole damn country is full of beggars. Paupers to a man, the Arabs. Jones empties his cup and once more curses his misfortune to be sent here of all places after the high society of Bombay where he hobnobbed with senior officers’ daughters and gambled copiously in the mess. The cellar in India was much finer than he expected and due to the large amount of Jocks in almost every regiment, the whisky, in particular, was excellent. By contrast, Arabia is an unforgiving country and although some of the officers seem almost to enjoy the hardship, Jones is not one of them. He is merely getting on with what he has to and hoping to get away with as much for himself as he can.