Полная версия:

The Winter’s Tale

There exists a curious paradox when it comes to the life of William Shakespeare. He easily has more words written about him than any other famous English writer, yet we know the least about him. This inevitably means that most of what is written about him is either fabrication or speculation. The reason why so little is known about Shakespeare is that he wasn’t a novelist or a historian or a man of letters. He was a playwright, and playwrights were considered fairly low on the social pecking order in Elizabethan society. Writing plays was about providing entertainment for the masses – the great unwashed. It was the equivalent to being a journalist for a tabloid newspaper.

In fact, we only know of Shakespeare’s work because two of his friends had the foresight to collect his plays together following his death and have them printed. The only reason they did so was apparently because they rated his talent and thought it would be a shame if his words were lost.

Consequently his body of work has ever since been assessed and reassessed as the greatest contribution to English literature. That is despite the fact that we know that different printers took it upon themselves to heavily edit the material they worked from. We also know that Elizabethan plays were worked and reworked frequently, so that they evolved over time until they were honed to perfection, which means that many different hands played their part in the active writing process. It would therefore be fair to say that any play attributed to Shakespeare is unlikely to contain a great deal of original input. Even the plots were based on well known historical events, so it would be hard to know what fragments of any Shakespeare play came from that single mind.

One might draw a comparison with the Christian bible, which remains such a compelling read because it came from the collaboration of many contributors and translators over centuries, who each adjusted the stories until they could no longer be improved. As virtually nothing is known of Shakespeare’s life and even less about his method of working, we shall never know the truth about his plays. They certainly contain some very elegant phrasing, clever plot devices and plenty of words never before seen in print, but as to whether Shakespeare invented them from a unique imagination or whether he simply took them from others around him is anyone’s guess.

The best bet seems to be that Shakespeare probably took the lead role in devising the original drafts of the plays, but was open to collaboration from any source when it came to developing them into workable scripts for effective performances. He would have had to work closely with his fellow actors in rehearsals, thereby finding out where to edit, abridge, alter, reword and so on.

In turn, similar adjustments would have occurred in his absence, so that definitive versions of his plays never really existed. In effect Shakespeare was only responsible for providing the framework of plays, upon which others took liberties over time. This wasn’t helped by the fact that the English language itself was not definitive at that time either. The consequence was that people took it upon themselves to spell words however they pleased or to completely change words and phrasing to suit their own preferences.

It is easy to see then, that Shakespeare’s plays were always going to have lives of their own, mutating and distorting in detail like Chinese whispers. The culture of creative preservation was simply not established in Elizabethan England. Creative ownership of Shakespeare’s plays was lost to him as soon as he released them into the consciousness of others. They saw nothing wrong with taking his ideas and running with them, because no one had ever suggested that one shouldn’t, and Shakespeare probably regarded his work in the same way. His plays weren’t sacrosanct works of art, they were templates for theatre folk to make their livings from, so they had every right to mould them into productions that drew in the crowds as effectively as possible. Shakespeare was like the helmsman of a sailing ship, steering the vessel but wholly reliant on the team work of his crew to arrive at the desired destination.

It seems that Shakespeare certainly had a natural gift, but the genius of his plays may be attributable to the collective efforts of Shakespeare and others. It is a rather satisfying notion to think that his plays might actually be the creative outpourings of the Elizabethan milieu in which Shakespeare immersed himself. That makes them important social documents as well as seminal works of the English language.

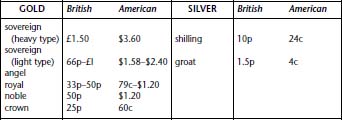

Money in Shakespeare’s Day

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to relate the value of money in our time to its value in another age and to compare prices of commodities today and in the past. Many items are simply not comparable on grounds of quality or serviceability.

There was a bewildering variety of coins in use in Elizabethan England. As nearly all English and European coins were gold or silver, they had intrinsic value apart from their official value. This meant that foreign coins circulated freely in England and were officially recognized, for example the French crown (écu) worth about 30p (72 cents), and the Spanish ducat worth about 33p (79 cents). The following table shows some of the coins mentioned by Shakespeare and their relation to one another.

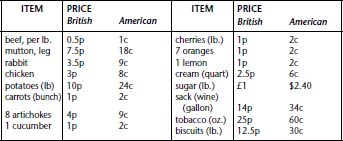

A comparison of the following prices in Shakespeare’s time with the prices of the same items today will give some idea of the change in the value of money.

INTRODUCTION

As a budding playwright, Shakespeare was attacked by an older writer, Robert Greene, for plagiarism: ‘an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers’. Towards the end of his career, for his next-to-last play to be completed, Shakespeare drew upon a story by this same Greene, and so created The Winter’s Tale.

In Shakespeare’s own period, older playgoers, remembering Greene and seeing this work for the first time, must have thought they knew how it ended. The king, consumed by jealousy, repudiates his queen, who dies. He soon after recognises his error, but it is too late. That, at least, is the story of Greene’s Pandosto. Shakespeare, however, picks up this simple tale and turns it into a myth of resurrection. We all, like the early playgoers, think Hermione to be dead. We see her fall, deadly sick, on stage. News of her death is brought by Paulina, whom we know to be a reliable witness. Sixteen years pass, without any sign of her.

Tragedy lies very close to comedy here. The earlier episodes, the autumn and winter parts of the play, display the imagery of disease and dearth: ‘Why then the world and all that’s in’t is nothing;/The covering sky is nothing; Bohemia nothing;/my wife is nothing; nor nothing have those nothings,/If this be nothing’. But those corrugated rhythms give way to the comedy of Autolycus and his song of spring: ‘When daffodils begin to peer,/With heigh! the doxy over the dale’. There is the daughter who was thought lost, Perdita in her harvest scene, also evoking the spring: ‘daffodils,/That come before the swallow dares, and take/The winds of March with beauty’. This prefigures the restoration of Hermione, which is the key to the play.

The meeting of Perdita with Leontes, her father, which could have been one of Shakespeare’s reconciliation set-pieces, is reported at second hand in order to preserve the grand climax for the restitution of Hermione. There, at the end, is the Statue Scene when Hermione rises, as though from the dead, and joins her repentant husband.

So far from attempting to seem naturalistic, the text drives home the impossibilities: ‘That she is living,/Were it but told you, should be hooted at/Like an old tale’. But Shakespeare has paid the ‘old tale’ of his former enemy, Robert Greene, the supreme compliment of turning it into high drama. Leontes says, ‘I saw her,/As I thought, dead; and have, in vain, said many/A prayer upon her grave’. However, the prayers have not been in vain. The whole scene is an acting out of resurrection.

The extravagance of the plot is matched by that of the structure. Such critics as the Italian, Castelvetro, and the Englishman, Sir Philip Sidney, thought that the Greek philosopher, Aristotle, had imposed rules on the drama that decreed restrictions as to the time a play should encompass in its action, the place – only one – it should represent, and the plot – very simple – that it should deploy. These rules were called ‘unities’, and Shakespeare violated these unities in an exuberant fashion. The action covers sixteen years, and not smoothly: there is a gaping void between Act 3 and Act 4. The scenes swerve between Sicily, the kingdom of Leontes, and Bohemia, the kingdom of his supposed rival, Polixenes. The plot, as we have seen, is far-fetched beyond all decorum. However, the appeal is not to the intricacies of art, but to nature. In the end, what we are shown is nature’s own cycle, represented in the death and restoration of Hermione. She is a kind of earth goddess. We see the earth die, every winter. Yet it revives in the spring. It is an idea similar to that of Jesus’ parable of the Prodigal Son. He ‘was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found’ (Luke 15:24).

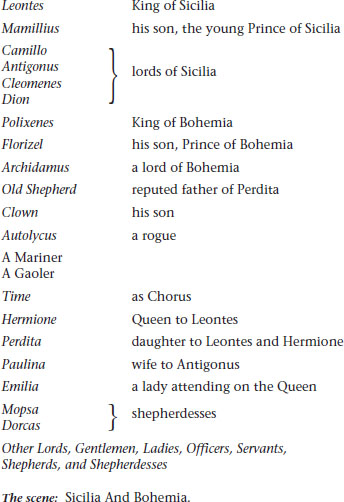

LIST OF CHARACTERS

ACT ONE

Scene I

Sicilia. The palace of Leontes.

[Enter CAMILLO and ARCHIDAMUS.]

Archidamus

If you shall chance, Camillo, to visit Bohemia, on the like occasion whereon my services are now on foot, you shall see, as I have said, great difference betwixt our Bohemia and your Sicilia.

Camillo

I think this coming summer the King of Sicilia means to pay Bohemia the visitation which he justly owes him. 5Archidamus

Wherein our entertainment shall shame us we will be justified in our loves; for indeed –

Camillo

Beseech you –

Archidamus

Verily, I speak it in the freedom of my knowledge: we cannot with such magnificence, in so rare – I know not what to say. We will give you sleepy drinks, that your senses, unintelligent of our insufficience, may, though they cannot praise us, as little accuse us. 10Camillo

You pay a great deal too dear for what’s given freely. 15Archidamus

Believe me, I speak as my understanding instructs me and as mine honesty puts it to utterance.

Camillo

Sicilia cannot show himself over-kind to Bohemia. They were train’d together in their childhoods; and there rooted betwixt them then such an affection which cannot choose but branch now. Since their more mature dignities and royal necessities made separation of their society, their encounters, though not personal, have been royally attorneyed with interchange of gifts, letters, loving embassies; that they have seem’d to be together, though absent; shook hands, as over a vast; and embrac’d as it were from the ends of opposed winds. The heavens continue their loves! 20 25Archidamus

I think there is not in the world either malice or matter to alter it. You have an unspeakable comfort of your young Prince Mamillius; it is a gentleman of the greatest promise that ever came into my note. 30Camillo

I very well agree with you in the hopes of him. It is a gallant child; one that indeed physics the subject, makes old hearts fresh; they that went on crutches ere he was born desire yet their life to see him a man. 35Archidamus

Would they else be content to die?

Camillo

Yes; if there were no other excuse why they should desire to live.

Archidamus

If the King had no son, they would desire to live on crutches till he had one. 40[Exeunt.]

Scene II

Sicilia. The palace of Leontes.

[Enter LEONTES, POLIXENES, HERMIONE, MAMILLIUS, CAMILLO, and Attendants.]

Polixenes

Nine changes of the wat’ry star hath been

The shepherd’s note since we have left our throne

Without a burden. Time as long again

Would be fill’d up, my brother, with our thanks;

And yet we should for perpetuity 5Go hence in debt. And therefore, like a cipher,

Yet standing in rich place, I multiply

With one ‘We thank you’ many thousands moe

That go before it.

Leontes

Stay your thanks a while,

And pay them when you part.

Polixenes

Sir, that’s to-morrow. 10I am question’d by my fears of what may chance

Or breed upon our absence, that may blow

No sneaping winds at home, to make us say

‘This is put forth too truly’. Besides, I have stay’d

To tire your royalty.

Leontes

We are tougher, brother, 15Than you can put us to’t.

Polixenes

No longer stays.

Leontes

One sev’night longer.

Polixenes

Very sooth, to-morrow.

Leontes

We’ll part the time between’s then; and in that

I’ll no gainsaying.

Polixenes

Press me not, beseech you, so.

There is no tongue that moves, none, none i’ th’ world, 20So soon as yours could win me. So it should now,

Were there necessity in your request, although

’Twere needful I denied it. My affairs

Do even drag me homeward; which to hinder

Were in your love a whip to me; my stay 25To you a charge and trouble. To save both,

Farewell, our brother.

Leontes

Tongue-tied, our Queen? Speak you.

Hermione

I had thought, sir, to have held my peace until

You had drawn oaths from him not to stay. You, sir,

Charge him too coldly. Tell him you are sure 30All in Bohemia’s well – this satisfaction

The by-gone day proclaim’d. Say this to him,

He’s beat from his best ward.

Leontes

Well said, Hermione.

Hermione

To tell he longs to see his son were strong;

But let him say so then, and let him go; 35But let him swear so, and he shall not stay;

We’ll thwack him hence with distaffs.

[To POLIXENES] Yet of your royal presence I’ll adventure

The borrow of a week. When at Bohemia

You take my lord, I’ll give him my commission 40To let him there a month behind the gest

Prefix’d for’s parting. – Yet, good deed, Leontes,

I love thee not a jar o’ th’ clock behind

What lady she her lord. – You’ll stay?

Polixenes

No, madam.

Hermione

Nay, but you will?

Polixenes

I may not, verily. 45Hermione

Verily!

You put me off with limber vows; but I,

Though you would seek t’ unsphere the stars with oaths,

Should yet say ‘Sir, no going’. Verily,

You shall not go; a lady’s ‘verily’ is

As potent as a lord’s. Will you go yet? 50Force me to keep you as a prisoner,

Not like a guest; so you shall pay your fees

When you depart, and save your thanks. How say you?

My prisoner or my guest? By your dread ‘verily’,

One of them you shall be.

Polixenes

Your guest, then, madam: 55To be your prisoner should import offending;

Which is for me less easy to commit

Than you to punish.

Hermione

Not your gaoler then,

But your kind hostess. Come, I’ll question you

Of my lord’s tricks and yours when you were boys. 60You were pretty lordings then!

Polixenes

We were, fair Queen,

Two lads that thought there was no more behind

But such a day to-morrow as to-day,

And to be boy eternal.

Hermione

Was not my lord

The verier wag o’ th’ two? 65Polixenes

We were as twinn’d lambs that did frisk i’ th’ sun

And bleat the one at th’ other. What we chang’d

Was innocence for innocence; we knew not

The doctrine of ill-doing, nor dream’d

That any did. Had we pursu’d that life, 70And our weak spirits ne’er been higher rear’d

With stronger blood, we should have answer’d heaven

Boldly ‘Not guilty’, the imposition clear’d

Hereditary ours.

Hermione

By this we gather

You have tripp’d since.

Polixenes

O my most sacred lady, 75Temptations have since then been born to ’s, for

In those unfledg’d days was my wife a girl;

Your precious self had then not cross’d the eyes

Of my young playfellow.

Hermione

Grace to boot!

Of this make no conclusion, lest you say 80Your queen and I are devils. Yet, go on;

Th’ offences we have made you do we’ll answer,

If you first sinn’d with us, and that with us

You did continue fault, and that you slipp’d not

With any but with us.

Leontes

Is he won yet? 85Hermione

He’ll stay, my lord.

Leontes

At my request he would not.

Hermione, my dearest, thou never spok’st

To better purpose.

Hermione

Never?

Leontes

Never but once.

Hermione

What! Have I twice said well? When was’t before?

I prithee tell me; cram’s with praise, and make’s 90As fat as tame things. One good deed dying tongueless

Slaughters a thousand waiting upon that.

Our praises are our wages; you may ride’s

With one soft kiss a thousand furlongs ere

With spur we heat an acre. But to th’ goal: 95My last good deed was to entreat his stay;

What was my first? It has an elder sister,

Or I mistake you. O, would her name were Grace!

But once before I spoke to th’ purpose – When?

Nay, let me have’t; I long. 100Leontes

Why, that was when

Three crabbed months had sour’d themselves to death,

Ere I could make thee open thy white hand

And clap thyself my love; then didst thou utter

‘I am yours for ever’.

Hermione

’Tis Grace indeed. 105Why, lo you now, I have spoke to th’ purpose twice:

The one for ever earn’d a royal husband;

Th’ other for some while a friend.

[Giving her hand to POLIXENES.]

Leontes

[Aside] Too hot, too hot!

To mingle friendship far is mingling bloods.

I have tremor cordis on me; my heart dances, 110But not for joy, not joy. This entertainment

May a free face put on; derive a liberty

From heartiness, from bounty, fertile bosom,

And well become the agent. ’T may, I grant;

But to be paddling palms and pinching fingers, 115As now they are, and making practis’d smiles

As in a looking-glass; and then to sigh, as ’twere

The mort o’ th’ deer. O, that is entertainment

My bosom likes not, nor my brows! Mamillius,

Art thou my boy?

Mamillius

Ay, my good lord.

Leontes

I’ fecks! 120Why, that’s my bawcock. What! hast smutch’d thy nose?

They say it is a copy out of mine. Come, Captain,

We must be neat – not neat, but cleanly, Captain.

And yet the steer, the heifer, and the calf,

Are all call’d neat. – Still virginalling 125Upon his palm? – How now, you wanton calf,

Art thou my calf?

Mamillius

Yes, if you will, my lord.

Leontes

Thou want’st a rough pash and the shoots that I have,

To be full like me; yet they say we are

Almost as like as eggs. Women say so, 130That will say any thing. But were they false

As o’er-dy’d blacks, as wind, as waters – false

As dice are to be wish’d by one that fixes

No bourn ’twixt his and mine; yet were it true

To say this boy were like me. Come, sir page, 135Look on me with your welkin eye. Sweet villain!

Most dear’st! my collop! Can thy dam? – may’t be?

Affection! thy intention stabs the centre.