Полная версия:

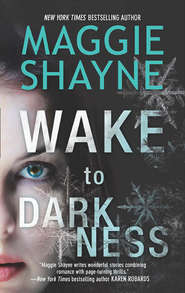

Wake to Darkness

Stranded with a murderer…

Rachel de Luca’s uncanny sense of perception is the key to her success as a self-help celebrity. Even before she regained her sight, she had a gift for seeing people’s most carefully hidden secrets. But the secret she shares with Detective Mason Brown is one she has promised to keep. As for Mason, he sees Rachel more clearly than she’d like to admit.

After a single night of adrenaline-fueled passion, they have agreed to keep their distance—until a string of murders brings them together again. Mason thinks that he can protect everyone he loves, including Rachel, by taking them to a winter hideaway, but danger follows them up the mountain.

As guests disappear from the snowbound resort, the race to find the murderer intensifies. Rachel knows she’s a target. Will acknowledging her feelings for Mason destroy her—or save them both and stop a killer?

Praise for the novels of Maggie Shayne

“Shayne crafts a convincing world, tweaking vampire legends just enough to draw fresh blood.”

—Publishers Weekly on Demon’s Kiss

“This story will have readers on the edge of their seats and begging for more.”

—RT Book Reviews on Twilight Fulfilled

“A tasty, tension-packed read.”

—Publishers Weekly on Thicker Than Water

“Tense…frightening…a page-turner in the best sense.”

—RT Book Reviews on Colder Than Ice

“Suspense, mystery, danger and passion—no one does them better than Maggie Shayne.”

—Romance Reviews Today on Darker Than Midnight

[winner of a Perfect 10 award]

“Maggie Shayne is better than chocolate. She satisfies every wicked craving.”

—New York Times bestselling author Suzanne Forster

“A moving mix of high suspense and romance, this haunting Halloween thriller will propel readers to bolt their doors at night.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Gingerbread Man

“[A] gripping story of small-town secrets. The suspense will keep you guessing. The characters will steal your heart.”

—New York Times bestselling author Lisa Gardner

on The Gingerbread Man

Kiss of the Shadow Man is a “crackerjack novel of romantic suspense.”

—RT Book Reviews

Wake to Darkness

Maggie

Shayne

www.mirabooks.co.uk

This book is dedicated to Eileen Fallon, my literary agent and sister-friend. Her keen eye and experience in the business, her ability to tell me gently and tactfully when I’m off track, and to scream loudly and boisterously with me when I nail it, her support and encouragement for more years than either of us will ever admit to, even under torture, are among the most valuable tools in my writer’s toolkit. And her friendship is one of the most cherished gifts I’ve ever received. Thank you, Eileen.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Prologue

Marissa Siorse’s new lease on life wasn’t supposed to end this way. Lying on her back on the cold ground, unable to move any part of her body. Her mouth was open wide as she tried and tried to breathe, and failed. Her lungs wouldn’t obey her brain’s commands. Her eyes were open just as wide, as the horror of what was happening played out in front of them. She wished she could close them, but she couldn’t, so she tried to focus on the leafless branches of the tree above her, and the sky beyond that. Blue, with soft, puffy clouds.

Then the ski-mask-covered face loomed over her, blocking out the sky. One gloved hand used a scalpel to slice the front of her dress open from hem to collar, laying her bare to the elements. To the cold. To the blade. That same hand had jammed a needle into her neck only minutes earlier, as she’d gotten into her car after a lunch date with her husband. She’d dressed up for him. Things were good between them. Better than ever. They hadn’t been. Life had been nothing but fear and struggle, up until her miracle. Back in August she’d been given a new pancreas. And after that, life had become a dream. She was strong now, maybe back to one hundred percent at this point, and looking forward to spending the rest of her life in the pink of health.

She’d had no idea that would be so short a time.

God, she was cold. Tears blurred her vision as she thought about her two kids. Erin was fourteen, halfway through her freshman year of high school and just now starting to get comfortable there. Cheerleading had been the ticket that got her through. And Mikey... Mikey was only eight. He needed his mother. And Paul. What the hell was Paul going to do without her?

Black spots started popping in and out of her vision. She wasn’t getting any oxygen to her brain. She was suffocating.

And then the hand brought the scalpel sharply across her skin, leaving a path of fiery pain just below her rib cage. Inside her mind, Marissa’s screams drowned out every other thought. But on the outside, she just lay there, still and silent. Until she died.

1

Friday, December 15

If the bullshit I wrote was true, I wouldn’t have been standing with my back to the man I’d most love to bone, saying “No.” Because if the bullshit I wrote was true, the question he’d just asked me would have been an entirely different one, instead of the one he’d asked, which had been, “Will you help me investigate another creepy fucking case that might get us both killed?”

Okay, those weren’t his exact words, but they might as well have been.

I was in Manhattan, in a TV station greenroom, getting ready for my live segment, and having him there was throwing me way off my game. Way off. I was tingling in places I shouldn’t be tingling, and remembering our one-night stand two months ago.

I should be remembering what happened after. The serial killer who damn near offed us both.

Mason Brown moved his oughtta-be-illegal bod around in front of me so I couldn’t not look at him. I knew he knew that. “I shouldn’t have sprung it on you like that. Should have started with hello. You look great, Rachel. Really great.”

“It’s the makeup. They overdo it for TV.”

“It’s not the makeup.” He tried his killer smile on me. A fucking saint would steam up at those dimples. “I’ve missed you. What’s it been, a month?”

Three weeks since I’ve seen him. Thanksgiving. Two months, nineteen days and around twenty hours since we’d had sex, last time I checked, but I’ll be damned if I’ll say that out loud. “Something like that.”

“Too long, any way you count it.”

“We agreed that we—” I waved my hand between us “—would be a bad idea.”

“Yeah, but I thought that meant we wouldn’t date.” And by date he meant screw. “Not that we wouldn’t ever see each other again.”

Except that seeing him made me want to jump his bones. Hence the not-seeing-each-other part. But I couldn’t tell him that, either.

“Look, Mason, I have five minutes before I have to be on that stage, in front of a live studio audience, hawking my new book, and you’re really throwing me off my Zen.”

“You have Zen?”

I closed my eyes. “No, but I fake it beautifully when I’m not...” Don’t finish that sentence. “What makes you think I’d be any help, anyway? I only connected with the Wraith because he had your brother’s heart, along with his penchant for murder, and I have your brother’s eyes, and we connected in some woo-woo way I’m still not sure I believe. It was a fluke, and it’s over. I’m no crime fighter.”

He put both hands on my shoulders. Yeah, that’s right, touch me and make it even harder for me not to rip your shirt off, you clever SOB. “Just give me a chance to tell you about the case. Come on, please?”

I closed my eyes, sighed hard and dropped my head to one side. When I opened my eyes again, he was flashing those damned dimples. He knew he had me. Hell, he’d had me at hello. The bastard.

“Buy me lunch after I finish up here and I’ll let you bend my ear, but that’s it, Mason.”

The door opened. “Two minutes, Ms. de Luca,” said the curly head that poked through.

I nodded and looked at Mason. His hands were still on my shoulders, and his smile had faded into an “I want to kiss your face off” sort of look.

I licked my lips, then wished I hadn’t. I reminded myself of all the reasons we’d decided not to “date.” I’d been blind for twenty years. Now I wanted to live my life as a sighted adult for a while before sharing it with anyone else. That made sense, didn’t it?

I couldn’t look at him. “I’ve gotta go.”

“Okay.”

“Fine.” I turned away from him and tried to school my face into that of a spiritually enlightened guru who could change every viewer’s life for a mere $17.99 in hardcover or $22.99 for the audiobook, plus tax where applicable. Only a fool would wait for the paperback or ebook versions, though they would be cheaper.

Mason sighed. Maybe in disappointment that I didn’t seem as glad to see him as he’d seemed to see me. A lot he knew. My inner idiot was doing cartwheels.

The door opened again. Polly-Production-Assistant came all the way in this time. “Ready?”

“Sure am.” Not even close.

She took my arm and led me out the door and through a maze of hallways. Mason was following right along behind us.

I turned to shoot him down over my shoulder. “I thought you were gonna wait in the greenroom?”

“I want to watch the taping. That’s all right, isn’t it?”

“Oh, sure, it’s fine,” said Polly or whatever the hell her real name was. “We’re in a commercial break, on in thirty seconds.”

She dragged me through a set of big double doors, and then we high-stepped over masses of writhing cables onto the set, stopping along the way so someone could run a mike up my back, under my dressy black jacket, over my shoulder and clip it to my flouncy lapel.

“Say something.”

“Mike check,” I said, looking through the window to where the sound guys wore headsets suitable for a firing range. “How’s it sound?”

They gave me unanimous thumbs-up, and I headed for the sofa. The show’s host, failed comedienne Mindy Becker, got up to shake my hand, then I sat down in the most flattering manner, uncomfortably on the edge of the sofa, legs crossed at the ankles, one hand resting lightly atop the other on my thigh. I wet my lips and plastered a great big smile on my face. I tried with everything in me to forget that Detective Mason Brown was standing a few yards away, watching my every move and hopefully wanting me as much as I was wanting him. He’d better be.

He knew my deepest secret, too, I thought. The secret only those closest to me knew. That I didn’t really believe in what I wrote. That I was a skeptic, feeding the gullible a steady diet of what they most wanted to hear—that the power to change their lives was in their hands—and laughing all the way to the bank.

And then the director said, “In three, two...” and pointed a finger at us.

“We’re back!” Mindy told the camera. “Joining us now is the bestselling author of Wish Yourself Rich, the book that’s sweeping the nation and changing lives, while spending its fifth week on the New York Times bestseller list. After going blind at the age of twelve, Rachel de Luca, the author who’s been teaching us how to make our own miracles for five years now, experienced one of her own when her eyesight was restored by a cornea transplant this past August.” She swung her head my way. “Welcome to the show, Rachel. I’m so glad to have you.”

“Thanks, Mindy. It’s great to be here.”

“I want you to know that I have read this...” Mindy picked up a copy from the arm of her chair. “...this gem,” she said, “from cover to cover, and I loved it so much I got copies for every single member of today’s studio audience as an early Christmas present.”

Applause, applause.

“I can’t tell you how deeply this book touched me.”

“Thanks, and thanks for saying that.”

“While the title is Wish Yourself Rich, this book is about so much more. About creating our own experiences, and actually having the lives we dream of. A lot of spiritual leaders today are saying many of the same things that you say in these pages, but, Rachel, you are the only one who is living, breathing, undeniable proof that it’s true.”

More applause.

“Why don’t we start at the beginning? You went blind at the age of twelve.”

I nodded. “It was a gradual process, but yes, eventually, I woke up one morning completely unable to see.”

“What was the last thing you remember seeing?”

Oh, good question. “It was my brother Tommy’s face.”

She made a sympathetic sound. “This is the brother you lost earlier this year?”

“Yes, just before I got my transplant. He was the victim of a serial killer.”

She set the book on her lap and, frowning, put her hands over mine. “How do you manage to have something like that happen and not let it rock your faith? You are so positive, so certain that we create what we focus on. How did you come to terms with your brother’s murder?”

It was not the first time I’d had this question. Thankfully, I was prepared for it. I wrote this crap for a living, after all. “Tommy’s journey was his own. I can’t know what his higher self intended for him, or why his life had to end the way it did. I only know that I have two choices. I can be at peace with knowing that he is at peace, trusting that everything happens for a reason and that I will know what those reasons are when my own time comes to cross to the other side, or I can wallow in misery and ask ‘why me’ and ‘why him’ and resent the universe for being so cruel. My brother is going to be just as dead, either way.”

“That is so deep,” Mindy said, shaking her head slowly. “So deep.”

“We get hung up when we think our happiness is dependent on circumstances outside ourselves. I’d be happy if only this would happen, we say, or if only that hadn’t happened. We have to let go of that and realize that happiness is a choice. When we can choose to be happy in spite of what’s going on outside us rather than because of it, when we can stop letting circumstances dictate how we feel, that is true empowerment.”

“That’s amazing. ‘Happiness is a choice.’ That’s so good.”

I smiled humbly. It really was one of my best nuggets of manure, that one. I rearranged this particular piece of...wisdom slightly after every interview, so it sounded fresh. Hell, I knew a thousand ways to say it by now. It was the core message of seven bestsellers.

“So did you always know you would get your eyesight back one day?”

“Not at all,” I said. “In fact, I’d pretty much given up on it. I’d had cornea transplants before, but I was one of those rare individuals who rejected them every time. And I rejected them violently. My doctor had to convince me that it was worth trying again with a new procedure.” That, at least, was true.

“And it worked.” Mindy clapped her hands to emphasize the words. “What was the first thing you saw after the bandages came off?”

“My sister’s face,” I said, again speaking the truth.

“Oh, that’s beautiful,” Mindy said in an emotional falsetto, blinking rapidly.

“So is she.”

Applause, applause.

Note to self, use that line again.

“So if we create our own experiences according to where we put our focus, how do you think you attracted your blindness?”

Because life sometimes sucks, and I drew the short straw. Because bad shit happens, and it doesn’t make any sense at all and it never will.

I nodded sagely while I pulled the appropriate well-rehearsed reply from my archives. I had them for all the tough questions. “Until we know that our thoughts and focus create our lives,” I said, “we sort of create by default. Our higher selves guide us toward the life we’re supposed to lead, and we either go with the flow or fight tooth and nail. I believe this was simply a part of my journey in this lifetime. I think I had agreed to it before I ever incarnated.”

“Really?” she said. “You really think all those years of blindness happened to you for a reason?”

“Absolutely.” Because I had shitty luck.

“And have you reached any conclusions about what that reason might have been?”

“I think I’ve pieced together some of it, but not all. I don’t think I’ll know all of it until I’m on the other side, looking back, reviewing my life and the lessons it taught me. But I do know that being blind led me to my career of writing self-help (bullshit) books like the ones my family used to (push on me) get for me when I was going through hard times. It led me to dear friends I might not have made otherwise, people in my transplant support group, the best friend I ever had in my life, Mott Killian, who’s since passed over himself, and my dog, of course.”

And Mason Brown. It led me to him. When he hit me with his car because I stormed into a crosswalk, blind as a bat and too mad to be careful. Helluva coincidence that he ended up donating his brother’s corneas to me later that same day. Helluva coincidence.

A big smile split Mindy’s face, and she lifted the book again, opened the back cover and turned it toward the camera, which caught a close-up of Myrtle sitting in the passenger seat of my precious inspiration-yellow T-Bird with the top down, wearing her goggles and yellow scarf, and “smiling” at the camera as only a bulldog could do, bottom teeth sticking up over her upper lip.

The audience laughed, then applauded again.

“Myrtle is blind, too,” I said. “I might not have taken in a blind old dog if I hadn’t been through what I had.” Odd, that was sappy as hell, and yet it was the absolute truth. Just like the bit I’d been thinking about the way Mason and I met. I should really be using this stuff more. But it made me uncomfortable to point to true things in order to prove my false claims. Muddied the waters. I liked clear lines between real life and my fictional nonfiction.

“That’s beautiful,” Mindy said. “That’s just beautiful. Thank you so much, Rachel. It’s been a pleasure having you. I hope you’ll come back.”

“Thank you, Mindy. I’d love to.”

She faced the camera again, holding up the book. “Grab a copy of Rachel de Luca’s Wish Yourself Rich, available now in hardcover and audio wherever books are sold.”

Applause, applause, applause.

“And we’re clear!” called the director.

I relaxed and automatically turned to see if Mason was still there.

He was. But he was looking at me with his head tipped slightly to one side, like Myrtle when I say the word food. Or the word eat or the word hungry or any word remotely related to a meal.

He’d just seen a Rachel de Luca he’d probably never met before. The public one. And now he was going to berate me for it throughout an entire lunch. This should be pleasant. Not.

* * *

Mason had never seen the side of Rachel he’d witnessed on that stage. He had read her books—the last three, anyway—and he’d skimmed the others. They were pretty much all the same—all about positive thinking and creative visualization and everything happening for a reason. He would probably have read more, because the message was so uplifting and empowering, if he hadn’t known that she didn’t believe it herself. Not a word of it.

It was the one thing he’d never liked about her. God knew he liked everything else about her a little too much. But that she was selling this spiel to the masses when she didn’t believe in it felt a little too cold, too calculating. It was a side of her that he found hard to take.

But today, just now, he’d seen a hint of something else. She might say she didn’t believe the stuff she wrote about. She might even think she didn’t believe it. But she wanted to. She had practically emanated a glow on that soundstage when she was going on about her positive thinking message. He was beginning to think it might not be an act at all.

Or maybe that was just wishful thinking on his part.

She’d kept the mask in place as she’d said her goodbyes to her hostess, and the entire time she’d signed autographs for the respectable-sized group who’d gathered outside on the sidewalk, despite the fact that it was cold and starting to snow. Then the crowd fell away as they walked up the sidewalk to find a place for lunch.

“It’s a great time of year to be in the city,” he said.

She nodded. The Rockefeller Center Christmas tree was all lit up, and every store window was decked to the nines. “I wish I could stay, but I’ve gotta get home to the kids.”

“Kids? Don’t tell me you got another dog.”

“No, Myrtle’s plenty. My niece Misty is dog-sitting, though.”

“At your place?”

She nodded.

“You’re a brave woman, leaving a seventeen-year-old alone in your home overnight.”

“Amy’s staying over, too.”

He grinned. “I don’t think your assistant is going to be much help, unless it’s to buy the booze for the inevitable party.”

“Don’t judge a book by its cover,” she quipped. “Amy may be all Goth-chick on the outside, but she’s super responsible, and besides, she hasn’t forgotten that I saved her ass a month ago.”

“We saved her ass a month ago.”

“Well, yeah. You helped.”

He laughed and meant it. It had been a while since that had happened. “Why only one twin with the dog-sitting? Is your other niece a cat person?”

“My sister and Jim took Christy with them for a two-week Christmas vacation in the Bahamas. She got the time off school but had to take her assignments along and promise to bring them back finished.”

“And Misty didn’t go?”

“Misty had the flu. Or at least she convinced my gullible sister that’s what it was. Frankly, I think it was more a case of not wanting to leave her latest boyfriend behind. The priorities of love-struck teens never fail to make me gag.” She did the finger-down-the-throat thing to make her point.

“I’ve missed the hell outta you,” he said, smiling at her gross gesture as if she were a supermodel posing in front of a wind machine. Then he added, “And your little dog, too.”

“She’s missed you, too.”

But he noticed that she didn’t say she had.

“Corner Deli?” she asked.

She’d stopped walking, and it took him a beat to realize she was suggesting that they should eat at the establishment whose wreath-and-bell-bedecked door they were currently blocking. He opened it. It jingled, and she preceded him in. They joined the line to the counter, ordered, and then she picked out a table to wait for their food. She headed for the quietest table in the crowded, noisy place. “Ahh, New York,” she said. “The only place where you can order a twenty-five-dollar sandwich that will arrive with a pound of meat and two square inches of bread.”

“And it’ll be worth every nickel.”

“Hell, yes, it will.” She was sparkling. Her eyes, her smile, told him she was as glad to see him again as he was to see her, whether she was willing to say it out loud or not. “So how are the nephews? I’ll bet this is a hard time for them.”

“It’s rough. Their first Christmas without their dad. It’s hard on all of us.”

She nodded slowly. “It’s my first holiday without my brother, too. I think that’s probably why Sandra wanted to get away. It’s too hard.”

“It’s rough. Sometimes I wonder if it would be easier if they knew the truth about Eric.” He looked at her as he said that. It was one of about a million things he’d been dying to talk to her about.