Полная версия:

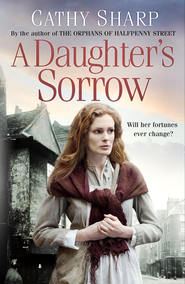

A Daughter’s Sorrow

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published as ‘Bridget’ in Great Britain by Severn House Large Print 2003

Copyright © Linda Sole

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Jeff Cottenden (girl); Heritage Images/Getty Images (background).

Linda Sole asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008168582

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008168599

Version: 2016-12-08

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Cathy Sharp

About the Publisher

One

The sound of a foghorn somewhere out on the river was almost lost in the noise of chucking-out time at the Cock & Feathers, known locally simply as the Feathers. Lying in my bed in the little room at the back of the house, I heard the usual screams, yells and scuffles from the pub at the end of the lane. I was used to it and it was not the petty squabbles of my neighbours that had woken me. No, this was something much closer to home.

‘Can I get into bed with you, Bridget?’

I smiled at the sight of my six-year-old brother dressed in a worn flannel shirt that was three sizes too big for him and reached down to his ankles. Beneath that ridiculous shirt was a painfully thin body; he was hardly more than skin and bone and worried me more than I’d ever let on to him or anyone else.

‘O’ course you can, Tommy. Was it them villains from the pub that woke you?’

‘It’s our mam,’ Tommy whispered, and coughed as he tugged the thin blanket up to his chest and burrowed further down into the lumpy feather bed my sister and I usually shared. ‘She’s having a right old go at Lainie again.’

No sooner had he spoken than there was an almighty crash downstairs in the kitchen. Tommy shivered and I folded my arms about him protectively as our mother suddenly screamed out a torrent of abuse.

‘You’re a slut and a whore – and ’tis after throwing you out of the house, I am.’

The spiteful words could be clearly heard by us as we lay in bed, Tommy shivering against my side as he always did when Mam was in one of her rages.

‘Whatever I am, it’s what you made me, and if I go you’ll be the one to lose by it, Martha O’Rourke. It’s four shillings a week you’ll be missin’ if I leave,’ Lainie shrieked, full of anger. ‘You’re a cold-hearted bitch and I’ll be glad to see the back of this place, but you’ll not take too kindly to going without your drop of the good stuff.’

‘And we all know where the money comes from! You’ve been down the Seamen’s Mission again, selling yourself to them foreigners.’

‘Hans loves me and one day he’ll be wedding me. You know he’s the only one, Mam. I don’t know why you take on so. Our da was working the ships when you met him – and our Jamie was on the way before the wedd—’

There was a scream of rage from downstairs and then more crashing sounds as furniture was sent flying. Our mother and sister were having one of their frequent fights, which always upset Tommy. They weren’t the only ones to indulge – similar fights went on in houses up and down the street, especially on a Friday night – but Martha O’Rourke could be vicious and I was anxious for my sister.

‘If your father was here, he’d take his belt to you!’

‘Give over, Mam …’ Lainie gave a little scream.

I jumped out of bed and hastily pulled on my dress. I was worried about my sister leaving. Lainie wasn’t going to put up with much more. She would walk out, and then where would the rest of us be?

‘Where are you going?’ Tommy said, alarmed.

‘You stop here. I’m going to creep down and see what Mam’s doing to our Lainie. She’ll kill her one of these days if no one stops her.’

Tommy clutched at my hand, his wide, frightened eyes silently begging me not to leave him. He was terrified of Mam when she was in one of her rages, and with good cause. We had all felt the back of Martha O’Rourke’s hand often enough. She was a terrible tyrant when she was in a temper.

Even as I hesitated, I heard Lainie slam the kitchen door and I knew I had to hurry, but Tommy was hanging on for dear life.

‘You’ll be all right here. I shan’t let Mam see me, and I’ll be back before you know it. There’s no need to worry, me darlin’.’

Leaving Tommy, I crept along the painted boards of the landing on bare feet and began a careful descent of the stairs. They were uncovered stained wood and creaked if you stepped on the wrong spot, but I had become an expert at avoiding the creaks. This was hardly surprising since I was the one who scrubbed them three times a week from top to bottom.

‘Lainie …’ I whispered as I saw her at the door. ‘Don’t go …’

Either she didn’t hear me or she was too angry to listen as she left the house and banged the door after her with a vengeance. I ran down the rest of the stairs as quickly as I could, forgetting to avoid the creaks in my hurry which brought Mam to the door of the kitchen.

‘And where do you think you’re going at this time of night? Off down the docks to be a whore like your slut of a sister, I suppose?’

‘I’m going after Lainie. You can’t throw her out, Mam. It isn’t fair!’

‘I’ll give you the back of me hand, girl!’ She started forward purposefully but I took a deep breath and dodged past her, knowing that I was risking retribution later. Lainie had to come back, it would be unbearable at home without her. Besides, where would she go at this time of night?

When I reached the street, I saw that she was almost at the end of the lane and I called to her desperately, running to catch up with her. She looked back reluctantly, then slowed her footsteps and finally waited for me at the top of the lane.

‘What do you want?’

‘You’re not really going to leave us, are you? I can’t bear it if you go, Lainie – I can’t!’

The note of desperation in my voice must have got through to her, because her sulky expression suddenly disappeared as she said, ‘Sure, it’s not the end of the world, Bridget darlin’. I’ll only be living a few streets away, leastwise until Hans’ ship gets back. After that, I don’t know where I’ll be – but I’ll be seeing you before then. You can come to me if you want me. If I stay here Mam will kill me – or I’ll do for her. I’m best out of the way. You know it’s true, in your heart.’

‘But we’ll miss you – Tommy and me. You know Jamie can’t stand to be around her …’

Jamie, our elder brother, was going on twenty and seldom in the house. Mam yelled at him if she got the chance, but he was a big-boned lad and she didn’t dare hit him the way she did us. He took after Da, who had a reputation for being handy with his fists, and would have hit her back.

‘I’ll miss both of you, me darlin’,’ Lainie said and her eyes were bright with tears she would not shed. ‘I can’t stay another day, Bridget. Sure, I know ’tis hard for you, darlin’, but you’ve Mr Phillips to help you – and our Jamie if you need him. Until he gets sent down the line, leastwise.’

‘Oh, Lainie!’ I cried fearfully. ‘He’s not in trouble again?’

‘When have you ever known our Jamie not to be in trouble? He’s like Da. He hits out first and thinks after. One of these days he’ll do for someone – and then they’ll hang him.’

‘Please don’t,’ I begged. I stared at Lainie’s pretty face, hoping that she was joking, but there was no sign of a smile in her soft green eyes. ‘I can’t bear it when you talk like that. Ever since Da drowned—’

‘Huh!’ Lainie flicked back her fair hair. She was as fair as I was dark and far prettier than I thought I could ever be. She also smelled of a sweet rose perfume that Hans had given her. ‘Mam has been lying to us, our Bridget. There was no body – no proof he drowned. From the way the old bill haunted us for months, I reckon they know the truth. Jamie says he was away on a ship to America.’

‘Do you think that’s what happened?’ I looked at her anxiously. I’d cried myself to sleep after Mam told us our father had drowned in the docks. I’d had nightmares about him being down there in the river somewhere, his body eaten by fish.

‘I shouldn’t be surprised,’ Lainie said. ‘They’re always looking for someone to take on down the docks. When crew have jumped ship or drunk themselves silly and not signed back on. Hans says it’s likely Da was taken on and no questions asked.’

‘Then he might still be alive?’

‘For all the good it will do any of us,’ Lainie said and pulled a face. ‘If he got away, he’ll not be after coming back. He’d be arrested as soon as they saw him. It was months before the law stopped hunting him. They haunted our Jamie at work, and watched the house. Da knows he’d hang for sure.’

‘Yes, I’m sure you’re right. It was better in the house before he left, that’s all.’

‘Only because he put his fist in her mouth if she opened it too wide. Don’t you remember all their rows?’

I remembered well enough, even though Sam O’Rourke had been gone for five years – years that his absence had made much harder for us all – but I also recalled Da giving me a halfpenny for sweets a few times. He had liked to ruffle my hair and call me his ‘darlin’ girl’.

‘Yes, I remember.’ I looked pleadingly at her. ‘You won’t change your mind and stay? Not even until the morning?’

‘I can’t,’ Lainie said and her mouth set into a stubborn, sullen line, which told me there would be no changing her. ‘Hans has begged me to leave home a thousand times. I only stayed as long as this for you and Tommy.’

‘What about your things? What are you going to do, Lainie? You can’t walk about all night—’

‘There isn’t much I want back at the house. I’m going to Bridie Macpherson. She’s asked me to work for her and she’ll provide uniforms. Hans will be back soon; he’ll give me money for what I need and then I shall go away with him. You can have my stuff and if I think of anything I want, I’ll let you know and you can smuggle it out to me.’

‘Will Hans marry you, Lainie?’

‘Yes.’ She smiled confidently. ‘He knows he’s the only one. I’ve never had another feller, Bridget. Mam carries on the way she does because he’s Swedish and not a Catholic, but Hans doesn’t care about that. He says he’ll convert if it’s the only way he can wed me.’

‘I’m glad for you.’ I loved my sister and I was going to miss her like hell, but I couldn’t hold her against her will. ‘Yes, yes, you must go, Lainie. It’s your chance of a better life.’

‘You’ll be all right,’ Lainie replied. ‘You’re clever, Bridget. I think you must take after great grandfather O’Rourke. He came over to England in 1827 when they were clearing the land for St Katherine’s Docks. They say he had a bit o’ money behind him, but he died of the cholera – there used to be a lot of it in the lanes in them days.

‘Grandfather O’Rourke was a lad of six years then, and his mother a widow with five small children. She had to struggle to bring them all up. When our grandfather was old enough to work, he started out as a labourer but ended as a foreman, running a gang under him. He would have done well for himself if he hadn’t taken a virulent fever and died. Leastwise, that’s what Granny always told us. Do you remember her at all?’

I had a vague memory of a white-haired woman in a black dress. ‘Yes, I think so. She used to sit on her doorstep and smoke a long-stemmed clay pipe, didn’t she?’

‘Yes.’ Lainie chuckled. ‘She died when you were about three. She was forever talking about the Old Country – and her brogue was so thick that I couldn’t always understand her.’

I stopped walking and looked back. We had already come a couple of streets and I knew Tommy would be waiting anxiously for my return.

‘I’d better get back then,’ I said and leaned towards her, kissing her cheek once more. ‘Take care of yourself, Lainie.’

‘You take care of yourself too, Bridget – and don’t let Mam bully you too much.’

I nodded, but it was easy for Lainie to say. She was nearly eighteen and she had someone who cared for her. I was almost a year younger and I couldn’t just walk out the way she had – someone had to watch out for Tommy.

Mam would be in a temper when I got back, but I was used to that. I hated to see Lainie go, but there was no point in making a fuss over spilled milk. I supposed Lainie ought to have left home long ago. She would be much happier working for Bridie – even though the hotel owner was a bit mean from all accounts.

I liked Mrs Macpherson, but then I didn’t have to work for her. She was a widow who had come to live near St Katherine’s Docks three years earlier and seemed to be a plump friendly person. When she had taken over the Sailor’s Rest, it had been a run-down hovel, but she had built it into a thriving business.

My thoughts were still with my sister as I walked slowly home, deliberately loitering despite the bitter cold, which was chilling me through to the bone. I knew what was waiting for me when I got back and I wasn’t looking forward to the row with Mam, who would take out her frustrations on me now that Lainie had gone.

It was only after a few minutes of walking on my own that I realized how late and dark it was in the lane. Most of the houses were shuttered, their lamps extinguished. I had never been out this late alone before. Nervously, I glanced over my shoulder as I sensed someone was watching me … following me even. Chills ran through me, giving me goose pimples all over; I was suddenly frightened.

The East End of London was a harsh dirty place in 1899, its air polluted by the smoke of the industrial revolution that had taken place throughout most of the past century. Crime was rife in the narrow lanes and alleyways that bordered the river and it was far from safe for a young woman to walk alone on a dark night. I began to walk faster, my heart jumping with fright.

The wind was blowing off the river bringing the stench of the oily water and refuse, dumped into the docks by the ships anchored out in the river, into the lanes, which already carried their own smell of decay. The houses here were better than the tenements a few streets away, but nearer to the river several deserted buildings harboured vagrants and rats.

I looked round again, but it was too dark to see anything. The suspicion that someone was following me sent prickles of fear down my spine. Lainie had often warned me about walking alone late at night. She’d told me that Hans always insisted that he walk her back to Farthing Lane after a night out.

When she was with him, Lainie was safe. Hans was a gentle man, but he was a blond giant with feet the size of meat plates and hands to match. One blow from him would knock most men’s heads off their shoulders. I’d met him once and he’d made me laugh with his stories about the days when the Vikings used to raid the English coast.

I wished Hans were here with me now or that my brother Jamie would come whistling down the lane to meet me. There was a man following me, I was certain of it now.

‘Where are you goin’? Bit late for you, ain’t it? Or ’ave you taken to walkin’ the streets for yer livin’?’

The voice was close behind me and made me jump. As I turned, I knew instantly who the voice belonged to and my fear abated slightly.

I lifted my head proudly, meeting that hateful, leering look on his face. Harry Wright had been after me since I was at school. Then he had been a snotty-nosed bully with no shoes and his arse hanging out of his trousers like all the rest of the kids in the lanes. Now he was dressed in a toff’s suit and leather shoes. He had made good and there was only one way to do that round here.

‘Who made it your business? Haven’t they locked you up yet, Harry Wright?’

‘Nah – and they ain’t goin’ ter neither,’ Harry said, eyeing me speculatively. ‘Leavin’ home then? Martha chucked yer out?’ he asked in his broad cockney accent. Harry was a Londoner through and through, but his manner was coarse and unlike most of the friendly people who lived in our lanes.

‘Take yourself off where you’re wanted,’ I retorted angrily.

‘Hoity toighty tonight, ain’t we? Got somewhere to go, ’ave yer? Only I could offer yer a bed fer the night – mine!’

Something in the way he looked at me was beginning to make me uneasy. ‘I’m going home – and I wouldn’t come with you if I wasn’t! I’d rather sleep under the bridge. So just you clear off, Harry Wright! I don’t want anythin’ to do with the likes of you …’

‘You’re too cocky for yer own good, Bridget O’Rourke!’ His eyes narrowed as he looked at me. ‘I bet yer a tart just like that bleedin’ sister of yours. Bin with a bloke down the docks ’ave yer? Yeah, yer a slut just like that Lainie.’

‘My sister isn’t a whore. You’re drunk, that’s what’s the matter with you. Just you leave me alone, Harry Wright! If you try anything I’ll tell Jamie and he’ll give you a thrashing.’

‘Stuck up bitch!’ he snarled and lurched at me, suddenly slamming me into the wall of the nearest house.

I could smell the stink of strong drink on his breath and knew I had guessed right: he was very drunk.

‘You’ve been givin’ it away to anyone who asks. Well, I’m takin’, not askin’. I’ll just ’ave a little taste of what yer’ve bin givin’ away …’

He was so strong and the pressure of his body was holding me pinned to the wall. I screamed once before his hand covered my mouth. Fear whipped through me but I was determined not to give in.

His hand was smothering me, making it difficult to breathe. I bit it as hard as I could and he swore, jerking back in pain and then striking me so hard across the face that I tasted blood in my mouth.

I screamed again, clawing at his face with my nails. My head was reeling and I hardly knew what I did as I struggled desperately to save myself. He was dragging my skirts up, clawing at me down there, where no man had touched me. I gave another cry of fear and pushed hard against him. For a moment I was able to wrench free of him, but he grabbed me and swung me round. I kicked out at him and then he hit me so hard my head went spinning. I gave a moan of pain and he punched me again, sending me crashing to the pavement. I hit my head hard as I fell, and then I knew no more.

‘What’s happening … don’t touch me!’ I screamed as the man bent over me and I stared wildly into the face of a stranger. ‘What are you doing to me? Leave me alone … leave me alone …’ I was almost sobbing now, hysterical. ‘Please leave me alone …’

‘Are you all right, lass?’ The man’s gentle voice was concerned as he knelt over me, helping me to sit up. ‘Someone attacked you. I think he was trying to – well, I believe I got here in time. You hit your head as you fell – does it hurt badly?’ He was touching my head as he spoke, feeling for the wound. ‘You’re bleeding. You must have fallen hard. It’s a wonder the bastard didn’t kill you! You should get your mother to bathe it for you. Where do you live – near here?’

‘Just down the road …’ I took a sobbing breath. I was beginning to remember. It wasn’t this man who had attacked me, in fact he had probably saved me from Harry Wright’s attempt to rape me. Shame swept over me and I hardly dared to look at him. ‘I’m all right … thank you for helping me. Are you sure he didn’t … you know?’

‘He was certainly attempting it,’ the man said. ‘I had been visiting a friend of mine, Fred Pearce, and I came out just as you fell.’ He smiled at me, a flicker of amusement in his greenish-brown eyes. ‘I think you can be sure that he didn’t manage it. He ran off when I yelled at him or I’d have thrashed the bugger for you!’

‘Thank you,’ I said again and blushed. I was overcome with shame as I realized that Harry Wright would have succeeded if it had not been for this stranger. I also wondered what I must look like with my clothes all over the place. ‘He … he frightened me. I was walking home and he followed me …’

‘Do you know him?’

I hesitated, then shook my head. If I told anyone that it was Harry Wright who had attacked me, Jamie would go wild. He would go after him and when he caught him, he would kill him. I didn’t care what happened to Harry Wright, but I couldn’t risk my brother getting into trouble over this.

‘No, I’d never seen him before in my life …’ I gave a cry of distress as I looked down at myself and saw that my dress had been torn and was stained with dirt from the road. ‘Mam will half kill me!’ I said and scrambled to my feet. ‘I’ve got to go …’

‘I’ll come with you,’ he said, steadying me as I nearly lost my balance. ‘Just in case that bastard is still hanging around. Besides, you look as if you need a hand.’

He was being kind but all I wanted to do was get away. My head hurt and I felt sick and dizzy and worst of all I thought that he must be thinking the worst of me – a common tart who’d fallen out with one of her clients.

‘No, thanks all the same. I’ll be all right in a moment. Mam will kill me for sure if she sees me with a feller. You can watch me until I get to me door, if you like?’

‘All right,’ he said and grinned as I dared to look at him again. He had a friendly smile, though he wasn’t a real looker; his hair was short and wiry and a sandy colour in the light of the gas lamp from Farthing Lane, but he had a nice manner and I knew I was lucky that he’d happened along when he did. ‘Cut along home then, lass. You’d best not keep your Mam waiting too long.’

‘Thank you for helping me. I’m Bridget O’Rourke. I don’t know your name …?’

‘I’m Joe Robinson,’ he said. ‘Take care of yourself. I’ll wait here and see as no one tries anything until you get home.’

I sent him an awkward smile and started to run, my heart pounding as my feelings rose up to overcome me. Inside, I was shaking, my mouth dry and my stomach riled. My head was sore where I’d banged it, but it was the feeling of shame that was so unbearable.

I had been attacked and almost raped! Things like that didn’t happen to decent girls, and I was certain Mam would go for me when I got in. She was already in a bad mood and when she saw the state I was in, she would lose her temper.