Полная версия:

Emma’s War: Love, Betrayal and Death in the Sudan

Emma’s War

LOVE, BETRAYAL AND DEATH IN THE SUDAN

Deborah Scroggins

For Colin

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

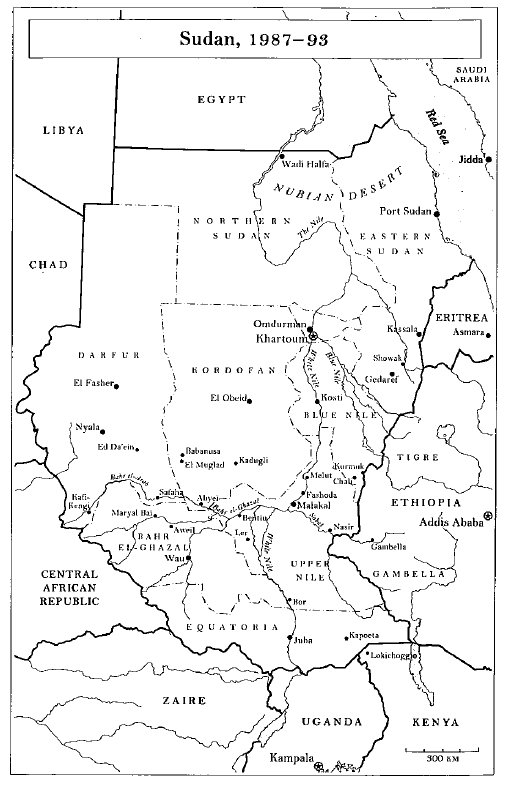

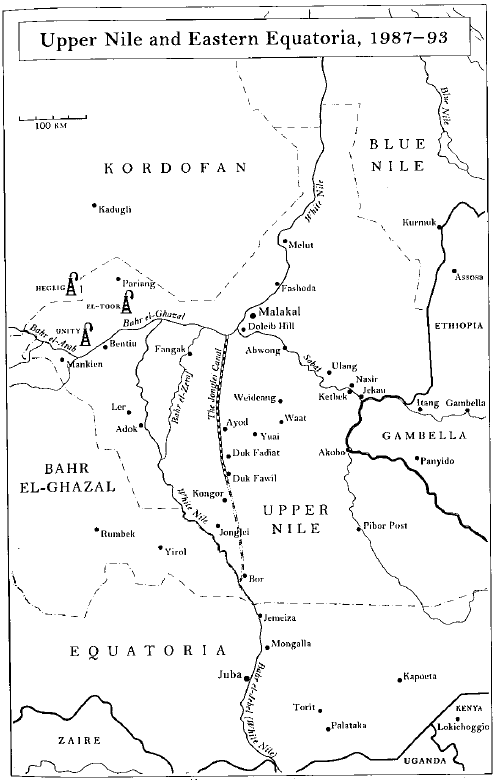

Maps

Prologue

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Part Two

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Part Three

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Part Four

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Part Five

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Epilogue

Images

Source Notes

Select Bibliography

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Author’s Note

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Even now, in the deep sweet busyness of a summer evening on Myrtle Street, I think of them. I’ll be giving my daughters a bath, there will be chatter and commotion and slippery little-girl bodies, and then suddenly I will hear the strange hum of the famine camp at Safaha, the sound of thousands of people coughing and gasping for breath, and I’ll remember how I lay awake listening to it. I will see my husband reading his book, and I will remember the contorted faces of the starving men who crossed the river and came to tell me something in a language I couldn’t understand. I will look out the window at the sun setting over the Atlanta skyline, and instead I will see Africa’s great violet ball of a sun sinking down over the river at Nasir. As the moon floats into view behind the branches of the big oak tree outside my house, I remember how it lit up the encampment outside the feeding centre at Safaha, turning the plain into a field of silver skeletons.

I think of them, and I remember Emma. I met her more than a decade ago in Nasir, a place that has been shrouded in ambiguity and irony from its beginning. An Arab slave-hunter hired by an Englishman to end slavery founded the town. A hundred miles east of the White Nile and eighty miles west of Ethiopia, it lies on the eastern edge of the seasonal swamp that makes up the better part of southern Sudan. Early in the twentieth century, the British established a command post there over the local people, a tribe of exceptionally tall and fearless cattle-keepers called the Nuer. By the time I reached it, Sudan’s civil war had destroyed most of the old town. The United Nations was delivering food at a crude airstrip made from the rubble of destroyed buildings. The rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) had located its provincial headquarters in a mud compound a few miles up the Sobat River from the ruins.

This was in December 1990, well before Emma McCune scandalized the region’s aid workers and diplomats by marrying the local warlord and going to live with him and his gunmen in that weapon-studded compound. But even then there was something unsettling about her. I was in Nasir working for the Atlanta newspaper. A photographer and I had been there for about ten days, reporting on the war between the Islamic government in the north and the Christian and pagan rebels in the south. I had been interviewing teenage soldiers and starving children. Since the war began in 1983, perhaps a million people had died, a quarter of them during the famine of 1988, which I had covered closely. Still there was an eerie beauty to this part of Sudan. The years of fighting had sealed it off from development, turning the blue-green wetlands between the White Nile and the Blue Nile into a vast wilderness refuge, whose silence was interrupted only by bombings, gunfire and the haunting songs of the local people.

The photographer, whose name was Frank Niemeir, and I had been waiting for several days for a UN plane to fly us back to Kenya. The plane had been delayed for the usual obscure reasons. Perhaps the government had banned flights to rebel-held areas; perhaps the UN was punishing the rebels for threatening to shoot down UN planes. No one knew. Or if they knew, they weren’t telling. Each day we walked up and down the banks of the Sobat, watching lyre-horned cattle roam through the ruins of what had once been a marketplace. We had seen a blue heron roosting on the wreck of an ancient steamer and marabou storks floating down the river on lily pads. In the evenings we had returned to the UN house, a derelict concrete structure of two rooms attached to a mouldering compound that had housed the American Presbyterian mission in Nasir. The missionaries had been expelled from Sudan nearly thirty years earlier, in 1964, but their houses were still the best Nasir had to offer. At night we played cards by the light of a paraffin lantern until we fell asleep on metal beds swathed in mists of purple mosquito netting we had brought from Nairobi.

At last an SPLA officer with bloodshot eyes and a T-shirt that bore the legend ‘Martin’s Restaurant, St Paul, Minn.’, came to tell us that the UN had radioed and a plane would be arriving shortly. We gathered up our backpacks and carried them through the ruined town to the edge of the airstrip, where we sat on top of them. The morning sun seemed to be looking down on us like a giant white eye. A couple of rebel soldiers stood around in flip-flops, listening for the plane. The first thing over the horizon wasn’t a plane but a man. He came out from behind the rusted hulk of a bus that lay on its side near the airstrip. He was a middle-aged Nuer with loose skin and the six parallel marks of manhood across his forehead. He wore a bunch of pink flowers in each ear, brass armbands and a pair of navy blue cotton underpants. His hair was dressed in cornrows, and he was singing and dancing his way towards us. Our rebel escorts stirred uneasily.

‘Who’s this?’ I asked.

‘He is no one,’ one of the rebels answered shortly. The soldier’s face was a mass of scars in the intricate dot patterns with which the southern Sudanese decorate their bodies; slung over his right shoulder was an AK-47.

The man with the flowers was only a few feet away now, gesticulating wildly, hopping up and down and pointing at us, singing at the top of his lungs.

‘What’s he saying?’ I asked.

‘He thinks he is a prophet,’ the first soldier said. ‘He says he has had enough now. You have been coming and going, but you don’t bring anything.’

‘He is a madman,’ the other soldier declared.

Frank took the man’s picture. I had been keeping a sort of diary of our trip in a small pink notebook I’d picked up in Nairobi. I took it out and wrote on the cheap brown paper:

Madman

flowers in his ears

feather in hair

shells on right arm

piece of notebook tied to left

like a mime

ring in nose

Those are the last words in that Nasir notebook, for just then we heard a high-pitched whine. For a moment I wondered what it was, still transfixed by the prophet. Then we saw the shadow of the plane’s wings. It was coming down in the tight corkscrew the pilots always performed in case someone started shooting at them. It landed, the engine sputtered into stillness, the rebels ran to open the door, and out jumped Emma. Frank and I stared. She was almost six feet tall, pale, dark-haired and slender as a model. She was wearing a red mini-skirt. An SPLA officer climbed out behind her; she and the officer were laughing about something. Emma threw her head back. She had large white healthy teeth. It was hard to believe she was flying in on an emergency relief mission. She looked as if she ought to be stepping out of a limousine to go to a party.

In a way, I was not surprised. I had heard about Emma. Young, glamorous and idealistic, she had sent a ripple of excitement through the social circles of the aid business when she went to work for a Canadian aid group called Street Kids International. In Nairobi, headquarters for East Africa’s burgeoning humanitarian industry, she had gained a reputation for wildness: adventures in the bush, all-night revels in the city. She was an Englishwoman with entrée to the city’s most exclusive expatriate circles, yet she was said to feel most at home with Africans. Some admired her nerve; others considered her dangerously naïve. I’d caught sight of her myself a few weeks earlier at the mess tent in Lokichoggio, or Loki, as we called it, the staging ground inside Kenya for the UN relief operations into southern Sudan. She had been drinking beer with a table full of African men, and she was talking with great animation. I couldn’t hear what she was saying, but I could tell that the men did not want her to stop.

Now in Nasir I thought I understood the current of disapproval that followed the stories about Emma. That gorgeous splash of a mini-skirt seemed almost indecent in a place filled with sick, hungry people catching their breath between bouts of vicious killing and mass starvation. To look happy seemed tactless - a flaunting of one’s good fortune. It occurred to me that the modest T-shirts and khaki shorts or blue jeans that were a kind of unofficial uniform for most of us expats were in some way an attempt to make ourselves sexless, at least in our own minds. We imagined that it announced, ‘We are not here to have a good time.’ It was like a surgeon’s scrub suit or perhaps a modern version of sackcloth and ashes: an unspoken signal that we thought we were wiser and more virtuous than the Sudanese and were in a kind of mourning for them. Not that the Sudanese were fooled. In truth the average aid worker or journalist lived for the buzz, the intensity of life in the war zone, the heightened sensations brought on by the nearness of death and the determination to do good. We wanted to be here, we were being paid good money to be here, and the Sudanese knew it.

On second thoughts, Emma’s mini-skirt seemed to me a refreshing departure from the usual pieties. It suggested that she was more honest than the rest of us, that she wasn’t afraid to admit she was here because she wanted to be here. She and I exchanged pleasantries, nothing more, and when I turned around to pick up my backpack, the man with the pink flowers in his ears had disappeared. I never saw him again, and I didn’t see Emma again for a long time. Frank didn’t take her picture, and I didn’t write about her in my notebook. But as the plane took off, I began to think about her for another reason that had nothing to do with clothes. I knew that she had been working closely with the SPLA’s ‘education coordinator’, a man called Lul Kuar Duek, to reopen Nasir’s schools. I myself had spent days in Nasir interviewing Lul about his plans for the schools. He had claimed to be a great friend of Emma’s. He was the kind of man the Nuer used to call a black Turuk, a name they took from Ottoman Turks who first introduced the Nuer to modernity when they invaded a century and a half earlier and that now extended to anyone who could read and write and wore clothes. Like most Nuer, Lul was dark as a panther, tall and thin with a narrow head and a loping walk. He was a former schoolmaster and an elder in the local Presbyterian church. He was also a bore and a bully. In the afternoons, he would drink Ethiopian gin out of a bottle and lecture me in his straw shack about the martyred American president John F. Kennedy and why southern Sudan was so backward and anything else that came into his mind. ‘The stage we are at now is the stage of the European in the stone age. We are in the age of stones,’ he would say, pointing his finger at me. ‘And you! You be careful. You should know you are talking to someone who knows everything.’

Lul’s baby son slept in a hammock next to his father’s automatic rifle during these conversations, and Lul would frequently offer to give him up for the cause of liberating Sudan from the domination of the Islamic government in the north. ‘Even this boy, he shall fight! Even if he should die! Even if it should take a hundred years…’ He recited the SPLA’s slogans with noisy fervour, insisting that the south would never settle for secession but would fight until the whole country had a new, secular government, though he was to be equally enthusiastic less than a year later when his fellow Nuer commander led a mutiny against SPLA leader John Garang on the grounds that the south ought to give up trying to change the north and start fighting for southern independence.

Like everyone else in Nasir, Lul was obsessed with a prophecy from the Book of Isaiah that he and the others believed foretold the future of southern Sudan. Whenever he had got about halfway through one of his gin bottles, he would wipe his hands on his red polyester trousers, take out the Bible from the crate beside his bed and start banging his hand on it. ‘It is all here - it is written!’ he would announce. Frank and I would exchange weary glances. ‘Isaiah eighteen. God will punish Sudan. People will go to the border with Ethiopia. “The beasts of the earth and the fowls shall summer upon them and all the beasts of the earth shall winter upon them.” I have seen all this come to pass. But it says that in the end we shall have a new Sudan.’

Lul was talking about the years in which hundreds of people had starved to death or been killed in the fighting around the town before the SPLA captured it from the government in 1989. Even then I wondered how Emma could stand it, handing out pencils to Nasir’s surviving children, while Lul raved on about fighting for another hundred years to make a new Sudan out of that blinding emptiness. I always made sure that Frank was with me before I went to visit Lul in his grass hut. But according to Lul, he and Emma got along famously. In fact, Lul was more interested in telling me about Emma than about the schools he was supposed to be running. ‘You know, Em-Maa’ - he pronounced her name with a satisfied smack - ‘is just like one of us. She walks everywhere without getting tired. She is bringing us so many things we need, like papers and chalks and schoolbooks. You people should know, our commander likes Em-Maa very much. Very much! And she likes him! She has been here, looking for him.’ Underneath the praise, there was something leering in his voice.

It was hard to imagine why my newspaper would want to know about an SPLA commander’s feelings towards a low-level British aid worker, and so I paid very little attention to Lul’s lewd suggestions. But when I learned, six months later, that in fact Emma McCune had married Lul’s commander, Riek Machar, the one who had ‘liked Em-Maa very much’, I remembered the mingling of lust and envy and contempt in Lul’s voice, and I felt obscurely frightened. Naturally I knew of ‘Dr Riek’, as the southern Sudanese called him. He was another black Turuk, but with a PhD from Bradford Polytechnic in England that made him the best-educated Nuer within the ranks of the SPLA. Westerners found him unusually smooth and affable, but we also knew that he was part of a violent and secretive guerrilla movement that was capable of the most ruthless cruelty. The news of Emma’s marriage provoked a surprising jumble of emotions in me. At twenty-seven she was just two years younger than I. I knew her only slightly, but the world of the khawaja - the Sudanese Arabic term for white people - is a small one, and she and I shared many friends and acquaintances among the aid workers, journalists and diplomats in Sudan. The same interesting British couple who had helped Emma get her job with Street Kids International, Alastair and Patta Scott-Villiers, had given me the tip two years earlier that led to my first big story in Sudan. A few days after I returned to Nairobi from Nasir in 1990, the Scott-Villierses had invited me to join Emma and a bunch of other people who were spending Christmas at Mombasa on the Kenyan coast (an invitation I had to decline, as I spent the holidays working in Khartoum that year). I had been writing about Sudan, off and on, for three years: it was the deepest and furthest part of my experience. Now here was Emma going deeper and further than I had ever dreamed of going, crossing over from the khawaja world into a liberation army led by men like Lul and the scarred gunmen at the airport, men responsible for some of the horrors she had been trying to alleviate as an aid worker. What, I wondered, had driven her to take such an extreme step? Later, after it was all over, I got the idea that her story might shed some light on the entire humanitarian experiment in Africa. Or at least on the experiences of people like me, people who went there dreaming they might help and came back numb with disillusionment, yet forever marked.

Part One

My first impressions of Sudan were rather blurred and uncertain; I was so much more interested in myself than I was in my surroundings.

— Edward Fothergill, Five Years in the Sudan, 1911

Chapter One

AID MAKES ITSELF out to be a practical enterprise, but in Africa at least it’s romantics who do most of the work - incongruously, because Africa outside of books and films is hard and unromantic. In Africa the metaphor is always the belly. ‘He is eating from that,’ Africans will say, and what they mean is that is how he gets his living. African politics, says the French scholar Jean-François Bayart, is ‘the politics of the belly’, The power of the proverbial African big man depends on his ability to feed his followers; his girth advertises the wealth he has to share. In Africa the first obligation of kinship is to share food; and yet, as the Nuer say, ‘eating is warring’. They tell this story: Once upon a time Stomach lived by itself in the bush, eating small insects roasted in brush fire, for Man was created apart from Stomach. Then one day Man was walking in the bush and came across Stomach. Man put Stomach in its present place that it might feed there. When it lived by itself, Stomach was satisfied with small morsels of food, but now that Stomach is part of man, it craves more no matter how much it eats. That is why Stomach is the enemy of Man.

In Europe and North America, we have to look in the mirror to see Stomach. ‘Get in touch with your hunger,’ American diet counsellors urge their clients. Hunger is an option. Like so much else in the West, it has become a question of vanity. That is why some in the West ask: Is it Stomach or Mirror that is the enemy of Man? And Africa - Africa is a mirror in which the West sees its big belly. The story of Western aid to Sudan is the story of the intersection of the politics of the belly and the politics of the mirror.

It’s a story that began in the nineteenth century much as it seems to be ending in the twenty-first, with a handful of humanitarians driven by urges often half hidden even from themselves. The post-Enlightenment triumph of reason and science gave impetus to the Western conviction that it is our duty to show the planet’s less fortunate how to live. But even in the heyday of colonialism, when Western idealists had a lot more firepower at their disposal, Africa’s most memorable empire-builders tended to be those romantics and eccentrics whose openness to the irrational - to the emotions, to mysticism, to ecstasy - made them misfits in their own societies. And the colonials were riding the crest of a wave of Victorian enthusiasm to remake Africa in our own image. If the rhetoric of today’s aid workers is equally grand, they in fact are engaged in a far less ambitious enterprise. With little money and no force backing them up, they are a kind of imperial rearguard, foot soldiers covering the retreat of a West worn down by the continent’s stubborn and opaque vitality. They may be animated by many of the old impulses, idealistic and otherwise, but they have less confidence in their ability to see them through. It takes more than an ideal, even an unselfish belief in an ideal, to keep today’s aid workers in place. Emma had some ideals, but it was romance that lured her to Africa.

Chapter Two

SHE WAS BORN in India, where her parents, Maggie and Julian McCune, had met and married in 1962, and the direction of her life, like theirs, was pounded and shaped by the ebbing tide of the British Empire. Maggie, a trim and crisp former secretary, still calls herself an ex-colonial, though the sun was already setting on colonialism when she was born in 1942 in Assam. She published a memoir in 1999 called Til the Sun Grows Cold about her relationship with Emma. The child of a loveless marriage between a British tea planter and an Australian showgirl who met on board a wartime ship, Maggie spent a lonely colonial childhood as a paying guest at various English homes and boarding schools. Emma’s father, Julian - or ‘Bunny’, as Maggie called him - was an Anglo-Irish engineer who had knocked around Britain’s colonies for at least a decade before he and Maggie settled down in Assam.

Theirs was an unfortunate match from the start. Maggie, shy and wounded, was only twenty-one when she was introduced to Julian on a visit to her father in India. She married him, she admits in her book, mainly to escape England and the hard-drinking mother whose theatrics she despised. With depths of neediness her husband never seems to have fathomed, she wanted nothing more than to bring up lots of children in the safe and conventional family she felt she had been denied as a child. Julian, fourteen years older, was a charming sportsman who thrived on admiration. He also liked his whisky. He seems to have been unprepared to bear any responsibilities beyond excelling at shirkar, the hunting and fishing beloved of British colonial administrators in India. Perhaps their marriage might have survived if they had been able to stay in India, where Julian, simply by virtue of being an Englishman who had attended some well-known public schools, was able to provide the luxurious lifestyle they had both come to expect.