скачать книгу бесплатно

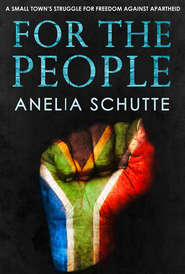

For The People

Anelia Schutte

A true story of small-town apartheidAnelia Schutte grew up in Knysna – a beautiful town on the coast of South Africa, centred around a picturesque lagoon and popular with tourists. But there was another side to Knysna that those tourists never saw. In the hills surrounding the town with its exclusively white population lay the townships and squatter camps where the coloured and black people were forced to live.Most white children would never go to the other side of the hill, but Anelia did. Her earliest memories are of being the only white girl at a crèche for black children that her mother, Owéna, set up in the 1980s as a social worker serving the black community.Thirty years on, Anelia, now living in London, yearns to find out more about her mother’s work, and to understand the political unrest that clouded South Africa at the time. She returns to Knysna to find the truth about the town she grew up in, from the stories and memories of the people who were there.For the People is an exploration of apartheid South Africa through the eyes of Owéna – a white woman who worked tirelessly for the black people of Knysna and found herself swept up in their struggle. They called her Nobantu: ‘for the people'.

A STORY OF SMALL-TOWN APARTHEID

Anelia Schutte grew up in Knysna – a beautiful town on the coast of South Africa, centred around a picturesque lagoon and popular with tourists. But there was another side to Knysna that those tourists never saw. In the hills surrounding the town with its exclusively white population lay the townships and squatter camps where the coloured and black people were forced to live.

Most white children would never go to the other side of the hill, but Anelia did. Her earliest memories are of being the only white girl at a crèche for black children that her mother, Owéna, set up in the 1980s as a social worker serving the black community.

Thirty years on, Anelia, now living in London, yearns to find out more about her mother’s work, and to understand the political unrest that clouded South Africa at the time. She returns to Knysna to find the truth about the town she grew up in, from the stories and memories of the people who were there.

For the People is an exploration of apartheid South Africa through the eyes of Owéna – a white woman who worked tirelessly for the black people of Knysna and found herself swept up in their struggle. They called her Nobantu: ‘for the people’.

For the People

A story of small-town apartheid

Anelia Schutte

www.CarinaUK.com (http://www.CarinaUK.com)

Contents

Cover (#uc88381c7-0b19-59a9-9641-3dace631b2b0)

Blurb (#u468e9c12-e458-5419-86f4-e419ce6daeff)

Title Page (#ua15a1e9c-4744-506a-a3fc-8f0289a013b4)

Author Bio (#u30eb17d4-2873-5cbc-9a89-ac9fa2bcecd8)

Dedication (#uc0b601a8-b598-5f80-a67c-d02b357cbcb9)

Author’s note (#u0209082b-915a-51dc-a03f-b2ec8ec51646)

Prologue 1984

Introduction

Chapter 1 Going home

Chapter 2 Back to my childhood

Chapter 3 1970

Chapter 4 Digging

Chapter 5 1970–1

Chapter 6 Colourful stories

Chapter 7 Xenophobia

Chapter 8 1972

Chapter 9 Jack and Piet

Chapter 10 1972

Chapter 11 1972–8

Chapter 12 Queenie

Chapter 13 The funeral

Chapter 14 1978–82

Chapter 15 1982

Chapter 16 Township tour

Chapter 17 1982

Chapter 18 Mrs Burger

Chapter 19 1983

Chapter 20 Crèche tour

Chapter 21 1983

Chapter 22 1983

Chapter 23 Oupad

Chapter 24 Tembelitsha

Chapter 25 1983

Chapter 26 Theron

Chapter 27 1983

Chapter 28 Memories of apartheid

Chapter 29 1983

Chapter 30 Johnny

Chapter 31 1984

Chapter 32 1986

Chapter 33 Lois Bubb

Chapter 34 1986

Chapter 35 Amy Matungana

Chapter 36 Trouble

Chapter 37 Esther Xokiso

Chapter 38 1986

Chapter 39 David Ngxale

Chapter 40 Lawrence Oliver

Chapter 41 1986

Chapter 42 1986

Chapter 43 Tapped

Chapter 44 1986

Chapter 45 Elizabeth Koti

Chapter 46 1987

Chapter 47 1987–8

Chapter 48 Winile Joyi

Chapter 49 1988

Chapter 50 Goodbyes

Epilogue 1994

Acknowledgements

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ANELIA SCHUTTE

has lived in Cape Town, Durban, London and New York, but she still calls Knysna home.

She’s been writing ever since she could hold a pencil: essays for school, poetry for fun, and eventually copywriting for a living. Her short story, The Unkindness of Ravens, was published in From Here to Here: stories inspired by London’s Circle Line in 2005. Somewhere in a drawer she also has an unpublished children’s story about a bullied dung beetle.

Now based in New York, Anelia is a creative director at language consultancy The Writer. The rest of the time she runs along rivers and over bridges, makes bobotie and rusks for her American friends and spends hours on the phone to her mother.

For the People is her first book.

For my mother and father,

for everything

Black South Africans:descendants of the many African tribes in South Africa, each with its own culture, language and traditions going back several thousand years. The most prominent of these are the Xhosa and Zulu people.

White South Africans: descendants of the Europeans who settled in South Africa from the mid-seventeenth century, notably the Dutch and the British. White South Africans fall primarily into two groups based on their native language: English or Afrikaans.

Coloured South Africans: people of mixed race with some African ancestry, usually combined with one or more lineages including European, Indonesian, Madagascan and Malay. Mainly Afrikaans-speaking, they’re also known as ‘bruinmense’ (‘brown people’).

Prologue (#u43cfd927-13f9-5d66-883a-364c6a4019c7)

1984 (#u43cfd927-13f9-5d66-883a-364c6a4019c7)

They call her Nobantu, but that wasn’t always her name.

While it is true that she was given that name in a church, it was far from a traditional christening. The church in question was little more than a shack; no spire, no bell, no stained-glass windows. Just a simple room with walls of corrugated iron. On the outside, those walls were painted red, the earthy terracotta of Klein Karoo dust. And so it was known as the Rooi Kerk – the Red Church – in the township called Flenterlokasie: location in tatters.

There were twenty-two women in the church that day. Twenty-two black faces under colourful headscarves, twenty-two bosoms squeezed into their smartest dresses (mostly hand-me-downs from their white madams). Strapped onto some of their backs were babies whose innocent faces peered out from under tightly knotted shawls, unaware of the hardship they’d been born into.

There were men, too, four of them, dressed respectfully in worn but neat suits.

They were the township committees, those men and women. Representing the townships to the west of Knysna was the Thembalethu committee, Thembalethu meaning ‘our trust’. And from the other side of town came the committee called Vulindlela, meaning ‘open the road’.

And that was how they arranged themselves in the Red Church that day: Thembalethu on the one side, Vulindlela on the other, twenty-two women and four men sitting on plastic chairs in their place of worship.

But they were not there to worship their God, not that day. They were there to honour a white woman.

For two years, that woman had been coming to their homes and changing their lives. She was the one who helped to start a crèche when she realised their children hadn’t held a pencil by the time they went to school. She was the one who took those children to the beach for the first time in their lives. She was the one who taught the local women to sew, when their only skill until then had been cleaning white people’s houses. She was the one who fought for their right to have more than one water tap serving an entire community.

For all of that they were honouring her that day, in a way reserved only for those who earned the respect and the love of the people. They were to give her a Xhosa name: a name they could use to greet her, to welcome her, and to call to her when they needed her.

The two committees had each chosen a name, which they wrote on a scrap of paper and placed on a table at the front of the church.

On the left, ‘Nobantu’: for the people. On the right, ‘Noluthandu’: the one with the love.

And then they began to sing.

They sang songs of joy and songs of hope, and as they sang the twenty-two women and four men formed a line and danced, single file, shuffling towards the tables.

And they reached into their pockets and into their bosoms, and on the name they felt most worthy of the woman, they placed their crumpled notes and sweaty coins – one rand, two rand, five rand, even ten. However much they had to give, they gave.