скачать книгу бесплатно

McQueen: The Biography

Christopher Sandford

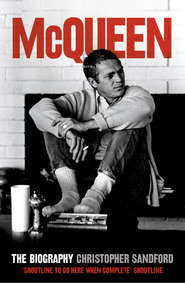

A full and frank portrait of the complex man behind the icon of cool.This edition does not include illustrations.Steve McQueen, one of the first ‘cool’ film stars, remains a cultural icon the world over. His image is used to sell everything from cars, to beer, to a range of dolls. From the Cincinnati Kid to Frank Bullitt, Tom Crown to Papillon, his roles exemplified a certain school of male charm, as well as grit and a hint of menace.McQueen was born in 1930 into a poor Mid-western family to a highly strung mother and truant father. In and out of reform school from a young age, he was eventually made a ward of court and the resulting sense of abandonment never left him. His big break came with the TV Saga Wanted: Dead or Alive and the now cult-classic B-movie The Blob. Just two years later he was one of the leading lights of tinseltown.Sandford goes on to chart McQueen’s phenomenal Hollywood career, starring in some of the world’s best-loved films, in tandem with his turbulent private life: his marriages, his bisexuality, the drink, the fast cars, casual sex and violence. As a close friend has remarked: ‘You couldn’t peg him. He wanted to be memorable as an actor – but in his private life you got the impression he was trying to speed up, to get into the next hour without quite living out the last one.’As Sandford reveals, McQueen’s public demeanour of studied nonchalance hid chronic self-destrutive urges which emerged in his favourite hobbies, including bare-knuckle boxing and porsche-racing, as well as several suicide attempts. His ‘lost’ years at the very height of his fame are illuminated with disclosures of rampant addiction, bizarre health cures, fringe religion and androgyny. McQueen died in 1980 at a ‘wellness’ clinic in New Mexico, having been earlier diagnosed with lung cancer . His last words were ‘Lo hice’ – Spanish for ‘I did it’.Sandford has spoken to a wide range of McQueen’s contemporaries – Hollywood stars, friends and family – and discovered the man behind the myth, the abandoned little boy underneath the movie-god swagger.

McQueen

The Biography

Christopher Sandford

Copyright (#ulink_7c486c2c-21ea-598c-ab0a-3045762c1d5d)

Harper Non-Fiction

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsEntertainment 2001

Copyright © S. E. Sandford 2001

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006532293

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2017 ISBN: 9780007381906

Version: 2017-01-13

For Robin Parish

‘The soul of the thing is the thought;

the charm of the act is the actor;

The soul of the fact is its truth, and the

NOW is its principal factor’

Eugene Fitch Ware

‘I’m a little screwed up, but I’m beautiful’

Steve McQueen

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u04b205e1-19e0-5b1e-8059-ce05a0784885)

Title Page (#uc9327094-3538-5782-b724-0bd22f39948c)

Copyright (#u9b75861b-32eb-5b89-b4f1-274e05fa1310)

Epigraph (#u75864d07-1dca-5713-a0e9-ebe2d08f49d1)

1 The American Dream (#ua13ba9ab-b4ae-571a-9ae5-809c5b1fc45e)

2 War Lover (#uf738c26a-c56c-5f87-a8e9-8c462797bc4e)

3 ‘Should I lay bathrooms, or should I perform?’ (#ubb62b8bf-9549-5fdd-bd7c-2936fc5e3e0a)

4 Candyland (#ueb682037-37fd-5d30-9f04-29f99d9a28c6)

5 Solar Power (#litres_trial_promo)

6 The King of Cool (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Love Story (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Abdication (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Restoration (#litres_trial_promo)

10 The Role of a Lifetime (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix 1 Chronology (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix 2 Filmography (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix 3 Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Sources and Chapter Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also By Christopher Sandford (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 The American Dream (#ulink_aba0e9c5-698a-5da4-b496-9d079c5d7686)

Steve McQueen was dead. It was a strange enough ending for a life that had scaled the heights of fame and plumbed the depths of depravity, laid out in a cold bare-walled room in a Mexican clinic. On this November morning a pale, watery sun came through the barred windows, sending chopped-up light onto the narrow bed. All the grief which marked the last year of McQueen’s life seemed purged by death. His eyes which, oddly, had turned dark grey were blue once more. In his hands was a Bible, turned to McQueen’s favourite verse, ‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.’ A doctor and a nurse both noticed the look that came over him at the end. It was the quizzical half-grin he made his own, that frighteningly unamused smirk at once attractive and not quite welcoming. Steve McQueen was himself again.

The king of cool had died at fifty. If the cancer hadn’t done for him, then a human agent had: according to McQueen’s doctor, it is ‘certain’ that a person or persons injected him with a fatal coagulant late on 6 November 1980, his final night alive. His patient was, he says, executed as he lay drugged and immobilised in a hospital bed. But no one should feel pity for Steve McQueen. He was neither broken nor bitter. Sick as he was, the happiest chapter of his life may have been the last one, in the care of Barbara, his third wife, flying his antique planes and slipping anonymously into church. He’d been living first in an aircraft hangar and then in a ranch with a big pot-bellied stove that filled half the room. Behind the house were fields and behind the fields were mountains. Here, in Santa Paula, California reminded Steve of the Missouri heartland he’d fled as a boy but never left. Here, the circle was complete.

A few other circles had been closed, too. McQueen’s first ever appearance on the big screen was as a prowling, knife-wielding punk. For his minuscule role as Fidel in 1956’s Somebody Up There Likes Me he earned $19 a day. Twenty-four years later, The Hunter ended on a poignantly downbeat note with McQueen spark out on a hospital floor. For that picture he made $3 million, plus 15 per cent of the gross. Running as a throughline in between, film audiences met one of the most arresting personalities in American art. Not too many others could hold a candle to McQueen’s striking affirmation of individuality. Far, far from the usual Hollywood pieties, Steve spent his off-duty hours dirt-biking or squatting in the desert with Navajo Indians. As a man, few ever came close to him. As an actor, nobody did. At his worst, McQueen gave off a quietly passionate sense of love and loss, eyes reeling with meaning, which perhaps promised more than it delivered. On peak form, he gave substance to even the thinnest plot. Not since the salad days of Brando had the words ‘movie’ and ‘star’ been in such proximity. Above all, McQueen knew that performance wasn’t a matter of right and wrong but of life and death – of the material. Jim Clavell, who worked up The Great Escape, would say that ‘Steve played suffering perfectly,’ since it chimed so well with his experience.

‘Lo hice – I did it’ were McQueen’s last known words. Towards the end, according to an orderly who was there, he ‘talked a lot about the early days, the farm, growing up and most of all reform school’. His nostalgia for the lost world of 1945 hid a grim truth: Steve had been committed by his own mother and her new husband. The squat bunker of Junior Boys Republic, the burr-cuts and bib overalls, the carbolic smell ground deep into the floor, the reek of the laundry – those were the stinking madeleines of his youth. And as McQueen lay dying, pressing ice cubes to his cheeks, doctors would hear him sob, ‘Three-one-eight-eight,’ over and over, his old school number of thirty-five years earlier echoing his fluttering heartbeat. Steve went out, if not with a whimper, then whey-faced for all the bewildered souls, not for his legendary groupies and least of all for Candyland, but for the ‘real folks’. For those who like their types cast, it was a quite heroic death.

They took him to the mortuary in Juarez, bumping along dusty roads where paparazzi from across the border already cowered behind trees. The Globe and Enquirer stringers squealed like game-show contestants when the car pulled in to the Prado Funerales. On that frenetic morning reporters were attempting to bribe medical staff with $80,000 for a shot of the corpse. In the end it was Paris Match who located McQueen’s body, calmly lifted the undertaker’s sheet and got off a picture for their front page. An orderly took exception and wound up rolling around with the photographer on the morgue floor. Later that afternoon the cortege made its way to the frontier town of El Paso, Texas, where a private jet stood fuelled and ready for the flight to Santa Paula. The sight of more press on the runway even as the plane revved up set off a round of groans and denunciations among McQueen’s friends. It was like the climactic scene from Bullitt. Two hours later they landed in California in thick fog. The plain Mexican coffin, flimsy for even his gaunt body, was loaded on a station wagon and taken to the Chapel of Rest in Ventura for cremation.

It was what McQueen had wanted, another perverse triumph. He’d always hated fires. He was nearly killed by one as a boy and in later years often had occasion to head-butt his demons. ‘You lookin’ at me?’ or a tart ‘Fuck you, candyass’ defiantly masked his inner terrors. Steve once ran through hot smoke to rescue his wife and young baby from a brush fire in Laurel Canyon. Drink and dope were balanced, for him, not only by fast cars but by constantly testing how he felt about himself and nature; and McQueen experienced that sense of challenge again in 1966, when he helped fight a three-alarm blaze at the studio. Ironically, the two worlds of fact and fiction finally merged eight years later when, at a routine briefing with the technical adviser on The Towering Inferno, McQueen responded to a real-life emergency by suiting up to save yet another torched stage. On that occasion a fireman looked over his shoulder, started and blurted out, ‘Holy crap! Steve! My wife won’t believe this.’ ‘Neither will mine,’ said McQueen calmly.

The body was burnt, and the ashes placed in a cheap urn. Steve had wanted ‘nothing fancy’ for himself, and he was famous for his spartan tastes – a can of Old Milwaukee was fine by him. Especially towards the end: by then, instead of goons and gofers, McQueen was keeping company with a distinctly rough-hewn crew of local barnstormers and pilots. Together they shared hobbies and traditions that were already old when Steve was born. They had an overriding love of keeping it simple, and many was the night they sat around the hangar, drinking and hugging themselves against the cold, whooping it up at Hollywood. This new McQueen was, above all, ‘real folks’, which is to say much the sort of person done on screen by the old McQueen. He favoured flying the flag in every school, early nights, and affirming the sanctity of marriage. That never ruled out a beer or a smoke. As for protocol, he didn’t overdo it. McQueen’s language was famously earthy. As far as acting went, he felt as if he’d pissed away about twenty years, wondering aloud what the fuck he’d been doing in half his films, although he always cashed the cheques. ‘You know, guys,’ Steve would say, squinting up at the snowy Rafaels, ‘I only really feel horny when I’m flying.’

They took the urn up in McQueen’s favourite antique Stearman, headed for the coast and scattered his ashes over the Pacific. That big bug. He’d loved it almost as much as he loved wheels. Fumes and altitude, the part of the American dream that went high and fast. Up there in the yellow biplane all the lines and wrinkles and what Steve called ‘broken glass’ were dissolved, blown away in the alpine air. They’d watched him, Sammy and Doug and Clete and the other flyboys, as he’d climbed sheer gradients, swooping with wild speed, and, just as fast, pulling back, rushing headlong towards the mountains, then levelling out at last towards the trails that went up into the hills and the clear sharpness of the peaks beyond. He would waggle his wings and it was exciting to him as though he were living, or at least exhaling, for the first time. That and the ranch and the silvered grey of the sagebrush, the quick, clear water of the Santa Clara and the missionary church were the sights and sounds he’d chosen for himself at the end. He’d always had a great imitative style, attitudes and poses associated with other people. But for the last year at least, Steve McQueen was playing himself.

That flight in the Stearman was a defining symbol of McQueen’s real breakthrough: that worldly success, for which he’d fought the System like two ferrets in a sack, was yet more ‘shit’. He was back to basics. Fire, air and sea were the true representation of Steve’s own words echoing down his last year – ‘Keep it elemental.’ His friends said a prayer for him over the water and came back low across the channel to Ventura. On McQueen’s orders, there was no grave or marker of any sort. His widow moved out of the ranch to a remote cabin in Idaho, and the plane and McQueen’s other goods were mainly given away. That, too, chimed with the ‘poor, sick, ragged kid’ who was father to the man.

Even Steve’s latter-day humility wasn’t enough to protect his cherished privacy. They came from all parts looking for clues, fans and paparazzi alike, doorstepping the ranch and swarming round his figure – soon removed by curators – at Hollywood’s wax museum. More than a few straggled back to the clinic, but none pierced the narcotic smog of medical debate, especially on the knotty subject of ‘alternative’ cancer treatment. Certainly nobody seriously floated the idea that McQueen had been murdered.

William Kelley, a one-time Texas dentist who apparently cured himself of cancer and went on to found the impressively styled International Health Institute, first treated a man posing as Don Schoonover in April 1980. ‘I told Schoonover – who turned out to be Steve – what he had to do. Sure enough, he began to get better…Six months later McQueen was in the clinic in Juarez and wanted to have his dead tumours surgically removed. I advised him of the risk, but Steve, being Steve, insisted. “I’m going to blow the lid off of the American cancer-treatment scam,” he told me. The medical establishment was freaked, shit scared of being exposed by a man like that. I was there the last night of his life, and I know what happened.’

A gutsy pioneer and whistleblower, or a demented nut? When Kelley started his institute, he had no surgical and little enough medical kudos. Even his orthodontist’s licence had been suspended after people complained that he was more interested in treating other health problems than in straightening teeth. A court injunction then briefly stopped publication of his book, One Answer to Cancer. By 1976 Kelley was being investigated by more than a dozen government agencies. For several years he and his wife moved onto an organic farm in Washington state, fantasised as a place of old-fashioned ideals, perfect peace, happiness and wholeness, with good vibes for all. He sold vitamins.

At this stage Kelley expanded his mail-order business and began hawking a ‘nonspecific metabolic therapy’ programme to patients disillusioned, like him, with the American Medical Association. His staggeringly complex nutritional regimen had some striking successes. Nobody knows exactly how many people are alive today because of him. However, after co-leasing the clinic in Mexico, Kelley achieved a series of remissions and apparent cures in even terminal cancer cases, McQueen allegedly among them. Both nurses and surgeons agree that the tumours removed from McQueen’s body were themselves already dead – ‘like cotton candy’, Kelley explains. ‘Steve was cancer-free for the last six months of his life. He died, pure and simple, of an induced blood clot.’ The accusation comes from a man, it has to be said, whose diet- and enema-based remedies landed him on the American Cancer Society’s blacklist. Some of Kelley’s deathbed scenario is also, like his therapy, nonspecific, but when his last doctor says ‘Steve was done in,’ you can be sure it’s because he believes it and not because of some slick dash he’s trying to cut. It would be astonishing if a freelance American celebrity like Kelley were vanity free, and he isn’t. With his treatment of McQueen already on record, he makes sure that people know of his other accomplishments – that he’s survived attacks by the FBI and the CIA, along with the ‘enemy Jew-controlled establishment’, for over thirty years. If Kelley’s racism repels, there’s still another strain in him that attracts as well. He talks fast, with a wheedling energy, but also with a wry humour and a string of wisecracks. Above all, he was there when Steve needed help, almost certainly prolonged his life, and was intimately involved in the events of 6–7 November 1980. Kelley may be a radical; he’s no nut.

Why did McQueen turn to what his first wife, at least, calls the ‘charlatans and exploiters’? The question still fascinates Hollywood’s ruling class who, for the most part, stood in such awe of him. Possibly because he felt so marginal – he never met his father and barely knew his mother – McQueen had the lifelong need to feud, to ‘twist people’s melons’, as he put it. Intrinsic to nearly everything he did was the sense of proving both himself and others. The truculence became part of this pattern, and any attempt to separate it from the gentler, mature Steve would split what’s indivisible. Throughout his life he was a cynic sometimes made credulous by his urge – almost a pathological need – to wing it. And McQueen would have automatically been well disposed towards anyone who, like Kelley, was at war with the world.

Sam Peckinpah, a man whose wit outlived his liver, put it best: Steve was every guy you didn’t fuck with. There are various mysteries about McQueen, shy kid and adult male equivalent of the Statue of Liberty, the chief one being that he seemed to be several different people. He was the insecure boy who didn’t much like being famous. Mostly he liked being alone, driving a straight ribbon of blacktop through the canyon dirt and past the lemon groves and orchards down into the desert. He loved the open spaces. Animals he usually tolerated but didn’t trust. People were ‘bad shit’. If there was any fellow-feeling, it was towards those he saw as other loners. There was the pill-popping and grog-quaffing McQueen who worked out three hours daily in the gym. There was the loving husband who boasted of ‘more pussy than Frank Sinatra’ on the side. There was the dumb hick (his phrase) who fought the studio system to a draw. The charismatic man who brought oxygen into a room. The last true superstar. The great reactor.

McQueen was the character who revels in his rebelliousness, the larger-than-life stud and free spirit who was actually a martyr to self-hate. During the periods when he wasn’t working Steve would get monumentally wasted, one of his typical pranks being when he stopped exercising and drank or snorted himself into oblivion. The pattern became a familiar one. While there was a suicidal component in some of these binges, McQueen didn’t actually want to die – the need for revenge was still too powerful for that. But he depended for his survival on a small but fanatically loyal gang of old friends; and his rude health. When most of those went south, and he made a genuine if tardy conversion to God, it’s not surprising McQueen pondered his options with Bill Kelley.

In the late 1960s, when Steve reached adulthood and suddenly realised he didn’t want to be there, the inverted world of movies was a wonderfully soothing place. McQueen’s personal myth, what he called his mud, ran to the bitter end. Many of the actual parts played were laughably weak, but McQueen was better than his scripts. Character counted with him, because in the end character was all there was. More than anyone, he knew that films exist in a kind of delicate balance with their moment. They can, sometimes mysteriously, either catch or miss their time. His own defining eloquence – a combination of the tough and the goofy – spoke directly to the embattled, mixed-up spirit of a war-torn republic. No one did the Sixties better than McQueen. He was, said Frank Sinatra, who would have known, ‘absolutely the greatest Zeitgeist guy. Ever.’

The designation was hard won. Obviously he wasn’t someone, like a De Niro, who physically aped his characters. The question of full-scale possession remains. All the fear and doubt and past experience McQueen brought to bear only heightened the surface dazzle of his cool under-playing. He didn’t call it a method: it was a policy, a life-plan of realism that was simply a part of him. It was also a good way for him to ‘twist melons’.

Karl Maiden remembers a scene he did with McQueen in The Cincinnati Kid. ‘Steve came on, in character, to confront me about whether I was double-dealing cards. He sprang at me like an animal. McQueen was prowling around the room where we were shooting, and he was absolutely terrifying. His fiery blue eyes were covered with an electric glaze and he was whipping about like a loose power line. He was so tense, I felt like I was gonna see an actor blow up for real…I mean, I was in awe of him.’ And this was a tough guy himself, who’d worked with Brando.

His aggression! People who knew and even loved Steve still marvel at it. It consumed him. The actor Biff McGuire remembers an odd and touching instance of it on The Thomas Crown Affair. This particular take called for McQueen to chip a golf ball out of a bunker, something that could have been done in a minute using a double or some other trick. ‘Steve toiled away at the shot most of the day, trying to hit the ball – going off to rest after a while, but then drawn back to it, totally focused on the job. He’d swing over and over and the ball would dribble up just a few inches and roll back in the pit again. Sometimes the director and crew would encourage him, but mostly I remember him alone, with that blinkered “Don’t fuck with me” expression of his, the club poised, then down, and the little shower of sand would spurt up. But everyone knew Steve would get the ball on the green, and in the end he did.’

He must have holed out just in time for his next – and best – picture, Bullitt. McQueen’s long-time friend (and sidekick in the film) Don Gordon was on location with him in San Francisco. ‘As well as kicking against the producers and suits generally, Steve applied his monster talent for competitiveness every night. First, he had both our motorbikes secretly shipped up from LA – secretly because the studio would’ve thrown a fit. He stowed them somewhere in a private lock-up. Around five every evening, just as the spring light was softening, Steve would yawn and announce he was turning in early. An hour later we’d meet at the garage and zip up into the hills, just the world’s biggest movie star and me, Steve thrilled like a kid breaking curfew but his edge immediately taking over.’ Gordon would good-naturedly watch McQueen put the throttle on and roar off into the dark. He ‘took it hard and fast because he was damn good, but also because he was stoked by knowing someone else was right behind him. I mean, Steve had to win.’

When McQueen died, more than twenty years ago, there was still a mythical America; an individual could still wrap himself in that myth. A large part of the legend had already gone Hollywood – not least in the lens of a John Ford or Frank Capra – before McQueen, but he also created his own. Vulnerability, decency and a real sense of menace all combined to fix him as the ‘new Bogie’, although Steve’s on-screen chemistry with women was the more toxic of the two. Some are put in mind of the ‘torn shirt’ school epitomised by Montgomery Clift and Brando, though McQueen’s reputation was always based on rather more than a few grunts and stylised nasal tics. With rare exceptions, he kept upping the risk, enlarging the dimensions of his own performance both on screen and off. Each of Steve’s roles was a grander and more precariously improvised adventure of the mind. His tragedy was that he could neither change the world nor ignore its creation of him. But it made for a life.

McQueen was able, out of his arrogance, to do something which was selfless. Of course he cashed the cheques, but in the best roles he created the walk, the look and the presence of the truly universal. Steve McQueen’s is the story of our time.

2 War Lover (#ulink_a559083a-8a8e-5636-900a-d7df6159844c)

Many of Steve’s first memories were of machines; they seemed to exert a pull on him from the start. They stood out, conspicuous against the human world, notable for their tireless, solid qualities, their efficiency, their resilience and power. They seemed responsive to his touch, and they were rational. He quickly found his place.

His time, early spring of 1930, was one of uneventful peace brooding over Europe. Britain grappled with its perennial labour and sterling crises and the worldwide trade slump, both cause and result of the Depression. The sovereign people of the US still lumped it under President Hoover, Advisory Boards on everything from Reconstruction Finance to Illiteracy marking the real beginning, three years pre-Roosevelt, of the New Deal. Yet, if lacking in surface drama, 1930 was still a turning-point, with two or three events of real long-term significance. In Germany the first Nazis took public office; on the sub-continent Gandhi began his civil disobedience campaign, with all the dislocation that entailed; and in the American rust-belt Steve McQueen was born.

It was a grim enough time, an icy 24 March, and a grim enough spot, the Indianapolis suburb of Beech Grove. He was delivered at ten that morning in the branch hospital, hard by the Conrail depot, where shabby passenger cars came to be fixed. Among the first sounds he would have heard were of engines. Everywhere more and more machinery was grinding: the city mills were still running at full bore and coal was being quarried in record weight. The factories blasted night and day; the clang of iron plates made a thought-annihilating thunder. The stockyards sent up a thick reek, wooden shacks standing beside animal swamps which bubbled and stank like stewing tripe. Dirty snow hillocks formed along the kerbs and sewage water ran raw and braided in the gutters. The inner slums, like Beech Grove, were already long since pauperised. Even the leprous hospital block was half-enveloped in weeds. This was the place, full of blood, stench and the sulphurous glare of the railyard, that fixed itself in the young boy’s imagination.

It’s often said that McQueen lived five lives, the juvenile and late years and one time around with each of his three wives. Like many people he used to wonder whether, in the last resort, those mewling early days weren’t the happiest and best. ‘I remember running in the hog yards…My people had this big field. And I’d come lighting out from school and play [there] and I remember how buzzed I felt.’ In later life Steve was skilled at softening hard memories with happy stories. His nostalgia for the 1930s and 1940s masked the grim truth that he was odds-on illegitimate, very probably abused and certainly unwanted. The experience left McQueen with the unshakable conviction that he was ‘a dork’, a friend explains. ‘He always described himself exactly that way. Steve was very sold on his being damaged goods.’

His mother, Julia Ann Crawford, known as Julian, was a nineteen-year-old runaway and drunk. In 1927 she’d taken off from the family farm for the city. Julian was blonde and pert, an apparently stylish and independent woman, if not the model of sanity. On closer inspection her very face was demented. Julian’s eyes, small and dark, suggested a substitute set of nostrils at the wrong end of her nose. At moments of excitement her head would loll wildly. She soon made a whole lifestyle out of being fractious. For a while it was only semi-prostitution, but before long Julian was dancing the hoochy-koochy and swigging ‘tea’, which she fortified from a silver flask in her handbag. Lipstick smudged across her pasty cheeks, face drawn, arms frail, black dress cinched round her thighs, stockings rolled down, she lurched from partner to partner, half gone but occasionally soaring into a shrill, manic high. The city authorities often called for her. Long before bi-polarity had a name, Julian was screwing herself in and out of madness.

In June 1929 she met and bedded an ex-flyboy named Bill McQueen. Steve’s mysterious father was one of those old-time rowdies who bent iron bars, pulled trains with their teeth or barnstormed at county fairs. All that’s known of his early days is that he flew in the navy and later toured North America with an aerobatic circus. Aside from drink, his two major loves in life were of planes and gambling. On his twenty-first birthday Bill came into a windfall of $2000. He took the cash and opened an illegal casino called Wild Will’s below a brothel on Indianapolis’s Illinois Street. After the club folded he became a drifter and an alcoholic. Around 1928 he began to suffer so badly from liver attacks and heart trouble that his doctor had to dull the pain with morphine. That set up yet another vicious circle of addiction. By the time Bill met Julian Crawford he was a sick man, in his late twenties but prematurely aged, with death all over him. They lived for a while in a rooming house, riding the trolley down to Schnull’s Block, the commercial zone, looking for work. None ever came. When Steve McQueen was born the following March, his parents had to apply for funds under the Poor Law. Julian took Bill’s surname, though there is no evidence they ever married. The father took off one night six months later, leaving the mother and son in a dismal hotel downtown. Bill came back once, a few weeks later, asking to be forgiven. Julian kicked him out.

Bill headed for the hills.

Steve’s claim that ‘my life was screwed up before I was born’ might be mawkish, but there’s no denying the shadow cast by this earliest ‘shit’, as he called it. Right to the end, he often quoted The Merchant of Venice, ‘The sins of the father are to be laid on the children’, sometimes substituting ‘of the mother’. The rich, famous and fulfilled man the world saw still considered himself a freak maimed for life by that early catastrophic shock.

In both manner and matter, McQueen was firmly tied to the fate of a bastard child of the 1930s. He rarely or never trusted anyone, and knew the value of a dollar as well as a crippling sense of doubt throughout years that were gritty and filled with struggle. It was a new world he grew up in, unique to the place, peculiar to the time; and, his friend confirms, ‘always, to Steve, something of a cross’. On the very morning he was born the weather broke in a filthy shawl of snow. Back in the rooming house the pipes had to be thawed with blow-torches while Bill brooded over his bottles. By day thick fog descended, leaving spectacular rime deposits on Market Street. At night the White river froze solid and the cold seemed to have the pygmy’s power of shrinking skin. Even in early spring, few of the locals ventured beyond the narrow confines of the city canal. Trains would haul freight and animals east, but rarely people. Some did claim they liked to travel, but they meant to Chicago perhaps, 130 miles north, or that they once visited St Louis. Indianapolis had few illusions about ever becoming world class. It was the typical submerged existence of the poor; people accepted it, hardly realising that their destiny could ever have been different. In short, it was the kind of place that teaches a boy to be practical while it forces him to dream of other, headier realities.

The past slowly faded: Civil War veterans, though a few still held court in Military Park; Indians, first as names and then as faces; even the great Jazz Age of the twenties. Culture in the Midwest was a marginal enterprise. The news that March Monday in the Hoosier Star was of Hitler, Gandhi and Stalin, and closer to home of Indianapolis itself, where the talk was of unemployment, foreclosures and the Ku Klux Klan. On the 24th fiery crosses burned on Mars Hill and the downs around Beech Grove, and the Catholic cathedral was pipe-bombed. Thugs terrorised Jewish shopkeepers. That long winter’s gloom wasn’t just climatic; it acted on the streets and the houses, but also on character, mood and outlook. It was a powerful depressant.

Nineteen-thirty was also, on another level, a time of mass escapism. The old music halls had gone, but the dramatic heart of the nation started up again in the movies. Sixty million men, women and children paid at the box office weekly. Mummified ‘flickers’ were fast giving way to modern production values: widescreen action in general and the Grandeur process in particular were blazed in 1930’s The Big Trail, starring John Wayne. The Depression would prove to be Hollywood’s finest hour. Disraeli, The Blue Angel and All Quiet on the Western Front were all soon playing amid a relentless diet of Dracula and primitive adult and slasher films. That same March Al Jolson opened in Mammy, while Garbo’s first talkie, Anna Christie, started out as an epic and soon mutated into something more, a picture Julian herself saw every night for a week. Between times, she would trudge with Steve to the downtown Roxy or sneak into the Crescent ‘colored house’, full of smoke, chrome and low-budget flickers which faded away to reveal the main visual drama – punch-ups and, in not a few cases, lynchings in the surrounding ghetto dealt out by the Klan. It was here that McQueen first made the acquaintance of sex and violence.

Meanwhile, more and more concerned women’s groups said that children could not be trusted around a cinema.

And yet the Daughters of the American Revolution probably weren’t unhappy. They had one cause of never-failing interest, and that was censorship. That same year Hoover established the Motion Picture Production Code, the so-called Hays Office, to police a growing trend towards blasphemy or crude Scandinavian naturism. Later in 1930 Loew’s on Meridian Street was actually raided during a live illustration of ‘civic hygiene’ involving two women, a tub and their silk smalls in a striking combination. According to the deadpan police report, ‘The sexual parts, around which the pubic hairs seem[ed] to have been shaved off, [were] clearly visible and so imperfectly covered by the wash cloth, that the lips bulge[d] out to the left and right of the towel…The glands were uncovered.’ Mae West’s celebrated trial on a similar morals rap opened in New York. This early, seminal association of the lively arts with sex and rowdyism was one Steve soon learnt and never forgot. Play-acting would give him the licence to be dirty, sweaty and lewd, the licence to get even, to make the real world vanish – and, eventually, to blow town. Once he started emulating the hoary two-reelers from Hollywood, it was only a matter of time for him and the rust-belt.

The pre-war decade was also a great flying era. Stunt pilots, barnstormers and wing-walkers attracted crowds undreamed of in the 1920s. Air displays sold out. In the same three-month period Charles Lindbergh and his wife set a transcontinental speed record, Amy Johnson made the haul from London to Sydney and Francis Chichester brought off the first solo crossing by seaplane from New Zealand to Australia. Bill’s intense devotion to this world reflected the same recklessness his son later experienced in drinking, drug-taking and dirt-biking. Like his father, Steve put himself on the line, on-screen and off; he dared all and he ‘went for it’ until self-destruction, or a sense of parody, kicked in. His whole career was the celluloid equivalent of the Barrell Roll. Long before he went aloft in his own vintage Stearman, McQueen had already flaunted his patronymic DNA – what Julian called the ‘butch, brawling, ballsy’ school of life. The winging it.

Born to poverty and bred to insecurity, Steve soon thrived on loneliness. He could never pinpoint how old he was when he first began to feel wretched in his own skin, but the critical scene haunted him the rest of his life. Running upstairs to the dive he shared with Julian, he suddenly heard her screaming, ‘hollering and howling [like] she was bein’ done in’ but accompanied, curiously, by gales of mirth from the neighbours’ stoop. His mother was in bed there with a sailor. ‘We ragged him,’ says a childhood friend, Toni Gahl. ‘Steve was very sort of geeky in those days. He was dirt poor, wore britches and Julian was no more than a prize slut. The other kids were down on him.’

So, suddenly, life became bewildering, and before he could even read or write McQueen was a reformatory case. His fate to always be the outsider was blazed early on. He was old enough to know he was ‘trash’, and young enough to dream about being part of a fantasy world in the movies. An imaginative, hyperactive child who would always rather be elsewhere, doing something else, Steve came to hate his mother even more than his runaway father. Every night he wandered among the drunks and rat-infested garbage while Julian turned tricks in their bedroom.

McQueen’s later binges were also a legacy of Bill’s – and Julian’s – world. What went into his movies was part of what went into his monumental craving for sex and drugs. The plethoric screwing, in particular, wasn’t normally for fun or pleasure; nor, says a well-placed source, was it ‘likely to thrill the girl. Steve was very much a wham, bam guy, not the kind to pour sap about love in your ear.’ That, too, echoed his father (motto: ‘They’re all grey in the night’), whose mark was in the boy’s marrow. His very names, Terrence Steven, were in honour of a figuratively legless, literally one-armed punter at Wild Will’s. The ‘McQueen’, from the Gaelic suibhne, meant ‘son of the good or quiet man’. As a derivative it was strictly out of the ironic-name school, and in fact, two choicer words could hardly be used to describe Bill. His own father had been a soldier, from a family of soldiers or sailors, who had moved from Scotland around 1750. By the early nineteenth century the McQueens were living in North and South Carolina before fanning out west at the time of the Civil War. An Arian (the ‘me’ sign), Steve was by a neat twist, within a few weeks’ age of both Sean Connery and Clint Eastwood, the three great ball-clanking icons of their era. The 24th of March was also celebrated in ancient Rome as the Day of Blood. Any child born that day was likely to be punished by an early death.

Julian’s people were devout Catholics and tradesmen in Slater, Missouri, gently rolling farm country midway between Columbia and Kansas City. For most of the 1930s she and Steve would shuttle from Indianapolis to the heartland and back, boarding with her parents and fostering an arbitrary highway persona, equal parts brief, ad hoc arrangements and cyclical transience, which he never broke. Much of McQueen’s on-screen insight came from the highly imaginative and disturbed five-year-old who once clutched his mother’s hand in genuine perplexity:

‘What’s wrong with us?’

Julian remained mute.

‘I’m starving, Ma.’

Julian was unaware of it at the time, but he was consumed with envy when he compared life even to that of the other slum kids in the city. Most of his peers were living in semi-comfort, while he had to content himself with cast-off clothes and meagre, wolfed-down meals. Toni Gahl remembers that Steve ‘didn’t say a lot. Basically he was pretty much of a clenched fist.’