Полная версия:

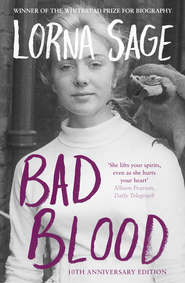

Bad Blood: A Memoir

LORNA SAGE

Bad Blood

Dedication

For Sharon and Olivia

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

PART ONE

I The Old Devil and His Wife

II School

III Grandma at Home

IV The Original Sin

V Original Sin, Again

VI Death

PART TWO

VII Council House

VIII A Proper Marriage

IX Sticks

X Nisi Dominus Frustra

XI Family Life

XII Family Life Continued

PART THREE

XIII All Shook Up

XIV Love – Fifteen

XV Sunnyside

XVI To the Devil a Daughter

XVII Crosshouses

XVIII Eighteen

Afterword

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

When Bad Blood was published a decade ago it made an unlikely star of its author, the 57-year-old academic Lorna Sage. Sage was already well known to the small but important pool of readers who followed her literary criticism in both newspapers and academic publications, but this was something else entirely. Her account of growing up in a grubby Welsh vicarage after the Second World War, getting pregnant at 16, and claiming the education, career and life which no one – family, school or culture – thought should be hers became the surprise hit of late 2000. The book sold hundreds of thousands of copies around the world, won the Whitbread Award for Biography together with the PEN/Ackerley Prize for autobiography and made Sage famous to people who would otherwise never have heard of her. In fact it was all a bit of a fairy tale – ironic when you consider that one of Bad Blood’s chief concerns is to cast a sceptical eye over the stories handed to us in childhood to steer by, regardless of whether they fit or hobble us horribly.

And then, just as the excitement reached a crescendo in the midwinter of 2000–2001, this late-to-the-party princess was gone. She had been felled by a complicated collision of asthma, emphysema and a fierce smoking habit, which made her cruelly short of breath. It had, though, also granted her the privileges of the chronic insomniac to read through the night, a habit begun in her childhood when she had been made restless by the face-ache of severe sinusitis.

Sage had been named after the heroine of one of her clergyman grandfather’s favourite books, R. D. Blackmore’s Lorna Doone, and if her life proves anything, it is that reading can make things happen. Not just in the old clichéd way – scholarship girl grafts her way to a life her parents could never have provided – but in the sense of giving Sage a keen sense of how stories work to shape our knowledge of self and the world. And how, most crucially of all, if a particular story doesn’t make sense, then you must simply make up a better.

The irony of the timing of her death would not have been lost on Lorna Sage. Unusually for a literary academic steeped in the critical theories of the Seventies and Eighties that declared the author dead, she was fascinated by the connections between writers’ lives and their works. And as an expert reader of memoir she would have known that you seldom get the neat double ending of text and life that had so spectacularly occurred with Bad Blood. As a result the book remains eerily intact, because there is no author on hand to expand, provoke or riff on it. We are left, as readers, an extraordinary freedom to make of it whatever we will.

Sage had been working on a memoir about her early life for some time, but it was the discovery of her grandfather’s diaries in the 1990s that suddenly gave shape to the book: it came out quickly, and in such a finished form that virtually no editing was required. These were the diaries, of course, which her grandmother had used to blackmail Revd Meredith-Morris into handing over most of his stipend. Full of details of his joyless philandering, the diaries would have been highly damaging if they’d got into the Bishop’s hands, which was exactly where Sage’s grandmother was threatening to put them unless ‘the old devil’, as she called him, paid up and paid regularly.

Described like this, Bad Blood sounds like a parochial book, in all senses. Yet when it appeared in the early autumn of 2000 it was a national and international hit, as if people had been waiting for it without quite knowing why. Perhaps it was to do with the fact that the world was now embarking on a new millennium. The mid-twentieth century with its watershed war and the unprecedented social changes that followed was about to be left behind for good. Very soon all the detail from that time – ration books, the eleven-plus, council houses, the nascent NHS, rural buses – would slip from living memory. Here was a last chance to see that world at first hand from someone whose intellect was briskly contemporary – mostly, indeed, ahead of the pack – yet whose life and mind had been forged in another age entirely.

Bad Blood, though, is much more than a social history of the war baby generation (Sage was born in January 1943 while her father was still away fighting). It is instead a story of absolute singularity involving one of the great tragi-comic characters of contemporary English literature, the Revd Meredith-Morris of St Chad’s, Hanmer, a rural parish situated in that thick finger of Wales which crooks oddly into Shropshire. The Old Devil is there for less than a hundred pages but he manages to dominate the whole book, with his great gusts of unhappiness, his boozy self-pity and of course his random lusts, which include trysts with the district nurse and his teenage daughter’s best friend. It is the Revd Meredith-Morris’s Bad Blood that circulates through the narrative long after he himself is gone, tainting everything it touches including little Lorna whose growing appetite for boys and books is darkly attributed to her grandfather’s sticky, vicious bequest.

Nor is it just the people in Bad Blood who are particular. Sage locates Hanmer precisely in time and place, giving us a muddy, midgy rebuttal to any expectation that the tale we are about to hear will be a pastoral one. This is Britain in the last gasp of the tenant farming system, before agribusiness rationalised production into huge regional food factories. The mud is Flintshire mud, rich and sucky and good for beef, though bad for stuck wellingtons. There are big dirty labouring families complete with the obligatory daft son and rusty machinery that takes an age to get going. Few of Sage’s readers will have experienced any of this at first hand, yet her extraordinary achievement is to make us feel that this story is somehow ours too. So while you may not have spent your early years living on rations, you know what a sly punch in the playground feels like. You may not have worn the complicated underwear that was de rigueur for older schoolgirls in the 1950s but you know what it is to feel uncomfortable in your own skin. Hanmer may have class gradations that seem as quaint as anything from Jane Austen, but which of us does not recognise that feeling of falling foul of some social tripwire we were too slow to see coming?

Still, the last thing Bad Blood wants is soppy identification on the part of its readers. Indeed, one of the most bracing things about the book is Lorna Sage’s indifference to making us like her. This blonde princess locked up in the gothic vicarage has bugs in her hair not because of some extraordinary drama of neglect or cruelty but because no one can be bothered to do anything about it. Her gaze, she tells us, is shifty and her default state sly. Had you known her as a child she almost certainly would not have wanted to be your friend, nor you hers. There is nothing remotely cosy here. And any idea that Sage is writing a misery memoir or asking for our pity is simply obscene.

The great joy of the book – and it is a joy – remains the way that this comic nightmare is delivered in the cleanest and clearest of language. As Professor of Literature at the University of East Anglia, Sage was sometimes required to be dense in her academic prose but you can really feel her exultation when she writes, as she did in her much-admired reviews in the Observer newspaper, for the Common Reader. She had a huge admiration for those authors such as Anthony Burgess who hacked to pay the bills, and a corresponding determination to reach the widest readership possible. And her talent is gloriously on show here, with that miraculous ability to conjure the Hanmer landscape, tricky turns in Britain’s post-war social development, and the inside of a priapic vicar’s brain, all without boring or baffling the reader for a moment.

Despite her scepticism about the coerciveness of certain kinds of stories, Sage does give us a happy ending of sorts in Bad Blood. She tells us how her life played out in ways that are clearly a matter of quiet pride. The Bad Blood, it seems, had finally been faced down. There was, though, one bit of the story which her sudden death in January 2001 left unfinished. She had been thinking about her memoir for so long. Now here it was, an enormous hit, making her famous around the world. What would she have done next? Another volume of autobiography? A novel even? Or more of that brilliant literary criticism which seemed to crack open the world of contemporary fiction with such deceptive ease? We will never know now and that, perhaps, provides the most tantalising ending of all.

I The Old Devil and His Wife

Grandfather’s skirts would flap in the wind along the churchyard path and I would hang on. He often found things to do in the vestry, excuses for getting out of the vicarage (kicking the swollen door, cursing) and so long as he took me he couldn’t get up to much. I was a sort of hobble; he was my minder and I was his. He’d have liked to get further away, but petrol was rationed. The church was at least safe. My grandmother never went near it – except feet first in her coffin, but that was years later, when she was buried in the same grave with him. Rotting together for eternity, one flesh at the last after a lifetime’s mutual loathing. In life, though, she never invaded his patch; once inside the churchyard gate he was on his own ground, in his element. He was good at funerals, being gaunt and lined, marked with mortality. He had a scar down his hollow cheek too, which Grandma had done with the carving knife one of the many times when he came home pissed and incapable.

That, though, was when they were still ‘speaking’, before my time. Now they mostly monologued and swore at each other’s backs, and he (and I) would slam out of the house and go off between the graves, past the yew tree with a hollow where the cat had her litters and the various vaults that were supposed to account for the smell in the vicarage cellars in wet weather. On our right was the church; off to our left the graves stretched away, bisected by a grander gravel path leading down from the church porch to a bit of green with a war memorial, then – across the road – the mere. The church was popular for weddings because of this impressive approach, but he wasn’t at all keen on the marriage ceremony, naturally enough. Burials he relished, perhaps because he saw himself as buried alive.

One day we stopped to watch the gravedigger, who unearthed a skull – it was an old churchyard, on its second or third time around – and grandfather dusted off the soil and declaimed: ‘Alas poor Yorick, I knew him well …’ I thought he was making it up as he went along. When I grew up a bit and saw Hamlet and found him out, I wondered what had been going through his mind. I suppose the scene struck him as an image of his condition – exiled to a remote, illiterate rural parish, his talents wasted and so on. On the other hand his position afforded him a lot of opportunities for indulging secret, bitter jokes, hamming up the act and cherishing his ironies, so in a way he was enjoying himself. Back then, I thought that was what a vicar was, simply: someone bony and eloquent and smelly (tobacco, candle grease, sour claret), who talked into space. His disappointments were just part of the act for me, along with his dog-collar and cassock. I was like a baby goose imprinted by the first mother-figure it sees – he was my black marker.

It was certainly easy to spot him at a distance too. But this was a village where it seemed everybody was their vocation. They didn’t just ‘know their place’, it was as though the place occupied them, so that they all knew what they were going to be from the beginning. People’s names conspired to colour in this picture. The gravedigger was actually called Mr Downward. The blacksmith who lived by the mere was called Bywater. Even more decisively, the family who owned the village were called Hanmer, and so was the village. The Hanmers had come over with the Conqueror, got as far as the Welsh border and stayed ever since in this little rounded isthmus of North Wales sticking out into England, the detached portion of Flintshire (Flintshire Maelor) as it was called then, surrounded by Shropshire, Cheshire and – on the Welsh side – Denbighshire. There was no town in the Maelor district, only villages and hamlets; Flintshire proper was some way off; and (then) industrial, which made it in practice a world away from these pastoral parishes, which had become resigned to being handed a Labour MP at every election. People in Hanmer well understood, in almost a prideful way, that we weren’t part of all that. The kind of choice represented by voting didn’t figure large on the local map and you only really counted places you could get to on foot or by bike.

The war had changed this to some extent, but not as much as it might have because farming was a reserved occupation and sons hadn’t been called up unless there were a lot of them, or their families were smallholders with little land. So Hanmer in the 1940s in many ways resembled Hanmer in the 1920s, or even the late 1800s except that it was more depressed, less populous and more out of step – more and more islanded in time as the years had gone by. We didn’t speak Welsh either, so that there was little national feeling, rather a sense of stubbornly being where you were and that was that. Also very un-Welsh was the fact that Hanmer had no chapel to rival Grandfather’s church: the Hanmers would never lease land to Nonconformists and there was no tradition of Dissent, except in the form of not going to church at all. Many people did attend, though, partly because he was locally famous for his sermons, and because he was High Church and went in for dressing up and altar boys and frequent communions. Not frequent enough to explain the amount of wine he got through, however. Eventually the Church stopped his supply and after that communicants got watered-down Sanatogen from Boots the chemist in Whitchurch, over the Shropshire border.

The delinquencies that had denied him preferment seemed to do him little harm with his parishioners. Perhaps the vicar was expected to be an expert in sin. At all events he was ‘a character’. To my childish eyes people in Hanmer were divided between characters and the rest, the ones and the many. Higher up the social scale there was only one of you: one vicar, one solicitor, each farmer identified by the name of his farm and so sui generis. True, there were two doctors, but they were brothers and shared the practice. Then there was one policeman, one publican, one district nurse, one butcher, one baker … Smallholders and farm labourers were the many and often had large families too. They were irretrievably plural and supposed to be interchangeable (feckless all), nameable only as tribes. The virtues and vices of the singular people turned into characteristics. They were picturesque. They had no common denominator and you never judged them in relation to a norm. Coming to consciousness in Hanmer was oddly blissful at the beginning: the grown-ups all played their parts to the manner born. You knew where you were.

Which was a hole, according to Grandma. A dead-alive dump. A muck heap. She’d shake a trembling fist at the people going past the vicarage to church each Sunday, although they probably couldn’t see her from behind the bars and dirty glass. She didn’t upset my version of pastoral. She lived in a different dimension, she said as much herself. In her world there were streets with pavements, shop windows, trams, trains, teashops and cinemas. She never went out except to visit this paradise lost, by taxi to the station in Whitchurch, then by train to Shrewsbury or Chester. This was life. Scented soap and chocolates would stand in for it the rest of the time – most of the time, in fact, since there was never any money. She’d evolved a way of living that resolutely defied her lot. He might play the vicar, she wouldn’t be the vicar’s wife. Their rooms were at opposite ends of the house and she spent much of the day in bed. She had asthma, and even the smell of him and his tobacco made her sick. She’d stay up late in the evening, alone, reading about scandals and murders in the News of the World by lamplight among the mice and silverfish in the kitchen (she’d hoard coal for the fire up in her room and sticks to relight it if necessary). She never answered the door, never saw anyone, did no housework. She cared only for her sister and her girlhood friends back in South Wales and – perhaps – for me, since I had blue eyes and blonde hair and was a girl, so just possibly belonged to her family line. She thought men and women belonged to different races and any getting together was worse than folly. The ‘old devil’, my grandfather, had talked her into marriage and the agony of bearing two children, and he should never be forgiven for it. She would quiver with rage whenever she remembered her fall. She was short (about four foot ten) and as fat and soft-fleshed as he was thin and leathery, so her theory of separate races looked quite plausible. The rhyme about Jack Sprat (‘Jack Sprat would eat no fat, / His wife would eat no lean, / And so between the two of them / They licked the platter clean’) struck me, when I learned it, as somehow about them. Looking back, I can see that she must have been a factor – along with the booze (and the womanising) – in keeping him back in the Church. She got her revenge, but at the cost of living in the muck heap herself.

Between the two of them my grandparents created an atmosphere in the vicarage so pungent and all-pervading that they accounted for everything. In fact, it wasn’t so. My mother, their daughter, was there; I only remember her, though, at the beginning, as a shy, slender wraith kneeling on the stairs with a brush and dustpan, or washing things in the scullery. They’d made her into a domestic drudge after her marriage – my father was away in the army and she had no separate life. It was she who answered the door and tried to keep up appearances, a battle long lost. She wore her fair hair in a victory roll and she was pretty but didn’t like to smile. Her front teeth were false – crowned, a bit clumsily – because in her teens, running to intervene in one of their murderous rows, she’d fallen down the stairs and snapped off her own. During these years she probably didn’t feel much like smiling anyway. She doesn’t come into the picture properly yet, nor does my father. My only early memory of him is being picked up by a man in uniform and being sick down his back. He wasn’t popular in the vicarage, although it must have been his army pay that eked out Grandfather’s exiguous stipend.

The grandparents weren’t grateful. They both felt so cheated by life, they had their histories of grievance so well worked out, that they were owed service, handouts, anything that was going. My mother and her brother they’d used as hostages in their wars and otherwise neglected, being too absorbed in each other, in their way, to spare much feeling. With me it was different: since they no longer really fought they had time on their hands and I got the best of them. Did they love me? The question is beside the point, somehow. Certainly they each spoiled me, mainly by giving me the false impression that I was entitled to attention nearly all the time. They played. They were like children, if you consider that one of the things about being a child is that you are a parasite of sorts and have to brazen it out self-righteously. I want. They were good at wanting and I shared much more common ground with them than with my mother when I was three or four years old. Also, they measured up to the magical monsters in the story books. Grandma’s idea of expressing affection to small children was to smack her lips and say, ‘You’re so sweet, I’m going to eat you all up!’ It was not difficult to believe her, either, given her passion for sugar. Or at least I believed her enough to experience a pleasant thrill of fear. She liked to pinch, too, and she sometimes spat with hatred when she ran out of words.

Domestic life in the vicarage had a Gothic flavour at odds with the house, which was a modest eighteenth-century building of mellowed brick, with low ceilings, and attics and back stairs for help we didn’t have. At the front it looked on to a small square traversed only by visitors and churchgoers. The barred kitchen window faced this way, but in no friendly fashion, and the parlour on the other side of the front door was empty and unused, so that the house was turned in on itself, against its nature. A knock at the door produced a flurry of hiding-and-tidying (my grandmother must be given time to retreat, if she was up, and I’d have my face scrubbed with a washcloth) in case the visitor was someone who’d have to be invited in and shown to the sitting-room at the back which – although a bit damp and neglected – was always ‘kept nice in case’.

If the caller was on strictly Church business, he’d be shown upstairs to Grandfather’s study, lined with bookcases in which the books all had the authors’ names and titles on their spines blacked out as a precaution against would-be borrowers who’d suddenly take a fancy to Dickens or Marie Corelli. His bedroom led off his study and was dark, under the yew tree’s shadow, and smelled like him. Across the landing was my mother’s room, where I slept too when I was small, and round a turn to the right my grandmother’s, with coal and sticks piled under the bed, redolent of Pond’s face cream, powder, scent, smelling salts and her town clothes in mothballs, along with a litter of underwear and stockings.

On this floor, too, was a stately lavatory, wallpapered in a perching peacock design, all intertwined feathers and branches you could contemplate for hours – which I did, legs dangling from the high wooden seat. When the chain was pulled the water tanks on the attic floor gurgled and sang. In the other attics there were apples laid out on newspaper on the floors, gently mummifying. It just wasn’t a spooky house, despite the suggestive cellars, and the fact that we relied on lamps and candles. All of Hanmer did that, in any case, except for farmers who had their own generators. In the kitchen the teapot sat on the hob all day and everyone ate at different times.

There was a word that belonged to the house: ‘dilapidations’. It was one of the first long words I knew, for it was repeated like a mantra. The Church charged incumbents a kind of levy for propping up its crumbling real estate and those five syllables were the key. If only Grandfather could cut down on the dilapidations there’d be a new dawn of amenity and comfort, and possibly some change left over. Leaks, dry rot, broken panes and crazy hinges (of which we had plenty) were, looked at rightly, a potential source of income. Whether he ever succeeded I don’t know. Since the word went on and on, he can’t have got more than a small rebate and no one ever plugged the leaks. What’s certain is that we were frequently penniless and there were always embarrassments about credit. Food rationing and clothes coupons must have been a godsend since they provided a cover for our indigence. As long as austerity lasted, the vicarage could maintain its shaky claims to gentility. There was virtue in shabbiness. Grandfather had his rusty cassock, Grandmother her mothballed wardrobe and my mother had one or two pre-war outfits that just about served. Underwear was yellowed and full of holes, minus elastic. Indoors, our top layers were ragged too: matted jumpers, socks and stockings laddered and in wrinkles round the ankles, safety pins galore. Outside we could pass muster, even if my overcoat was at first too big (I would grow into it), then all at once too small, without ever for a moment being the right size.