Полная версия:

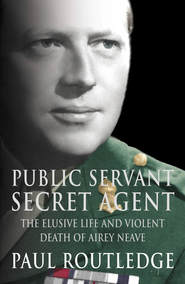

Public Servant, Secret Agent: The elusive life and violent death of Airey Neave

PUBLIC

SERVANT,

SECRET

AGENT

The Elusive Life and Violent Death of Airey Neave

Paul Routledge

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Preface

1 The Price of Liberty

2 Origins

3 King and Country

4 Capture

5 Colditz

6 Escape

7 Operation Ratline

8 Secret Service Beckons

9 Enemy Territory

10 Nuremberg

11 Lawyer Candidate

12 The Greasy Pole

13 Locust Years

14 A Very Spooky Coup

15 In the Shadows

16 Plotting the Kill

17 Pursuit and Retribution

18 The End of the Trail

References

Index

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

A gun lay unobtrusively on the settee beside my polite host, and the heavily-built man sitting on an armchair in the corner wore a tight-fitting black mask with tiny holes for his eyes and mouth. He was on edge and there was a tension in the room. I had come a long way, physically and in time, to see the killers of Airey Neave, and here I was, face to face. Not with the men who planted the bomb on 30 March 1979, almost twenty-two years ago to the day, but with ‘someone connected with the Neave operation’ who belonged to the small but highly dangerous Irish National Liberation Army.

The trail started five years earlier, when I was writing a biography of John Hume, leader of the SDLP, a shrewd nationalist and a rock for thirty years in the maelstrom of Irish – and British – politics. Hume crossed paths with Neave, the Conservatives’ Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary, many times during the late 1970s. It was not a profitable relationship. Hume found Neave’s traditional Tory attitudes towards Ulster Unionism and his militarist stance on the Troubles short-sighted and unsophisticated. Neave probably thought the former trainee priest slippery and threatening. He had, after all, engineered the short-lived exercise in political power-sharing that the Tory spokesman on Ulster utterly rejected.

Neave’s impact on policy towards Northern Ireland during the four years he held the Shadow portfolio was limited, but his death at the hands of terrorist assassins in the precincts of the House of Commons convulsed politics and prompted the question in my mind: ‘Who was this man?’ There was no biography of Airey Neave, yet he had lived an eventful life. Eton, Oxford and the Inns of Court were followed by capture in the siege of Calais, prison camps, escape from Colditz and service in military intelligence. He had served the indictments on Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg and entered Parliament at his third attempt in a by-election. A promising ministerial career was cut short by a heart attack, and he seemed destined to live out his political career in back-bench obscurity until the social upheavals of the 1970s propelled him into history as the man who gave us Margaret Thatcher.

It was a remarkable story, but no one had written it. I therefore resolved to do so and began collecting material. It was clear from the outset that Neave’s family (his daughter Marigold and two sons, Patrick and William) were apprehensive about the project. Neave had not wanted a biography, beyond the books he had written about his life, nor did his widow, Diana, who died in 1992. Other approaches, I knew, had been rebuffed and I was hardly the writer of choice. Yet I persisted and the family finally agreed to cooperate, though not on a lavish scale.

Much more difficult was ‘the other side’ – the perpetrators of the murder. Over the years reporting from Ulster, through a republican contact I will not name, I had learned something of the Irish Republican Socialist Party, the political wing of INLA. After an initial social meeting in a Belfast bar, at which I outlined my intentions, I let the seeds germinate. Then, in the autumn of 2000, I approached the IRSP directly, and arranged to visit the party’s headquarters in the Falls Road, the heart of republican Belfast. The taxi driver who took me there on 17 November advised against going into the pub opposite. ‘Not with your accent [Yorkshire],’ he grinned. Seamus Costello House, a large red-brick villa (allegedly bought with the proceeds of a bank robbery) is protected by steel mesh fortifications. A photographic tableau of the dead hunger strikers stands outside. Inside, the atmosphere is more homely, reminiscent of an old-fashioned trade union branch office, with people asking for advice and children playing about their mothers’ knees. Banners and framed slogans decorate the walls. The furniture is utilitarian. Everyone smokes.

Paul Lyttle, the IRSP’s spokesman, listened courteously to my pitch. It was clear from the first that my credentials had already been thoroughly checked. They knew who I was and where I was coming from before I opened my mouth. So, indeed, did the security services. This visit was known in London before I returned the following day. I told Lyttle that I wanted to write an account of Neave’s death that was as authentic as possible. To that end, I wished to meet the killers, if possible; and if that could not be arranged, then to talk to INLA ‘volunteers’ involved in the operation. There had been many accounts of the assassination, mostly conflicting. Was it not now time for the truth?

The door seemed to be ajar. The IRSP man dwelt on the dangers that Neave presented to militant republicanism, being one of the few British politicians who (as an ex-POW) knew just how critical was the morale and organisation of ‘the men behind the wire’. However, those men had virtually all been released under the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and yes, the organisation might be willing to brief me. A decision would have to be taken by ‘the executive’, and this process would take some time. It was also plain that the IRSP/INLA felt that the assassinations of four of their top people in the aftermath of Neave’s death should receive the same kind of public scrutiny currently being given by the Savile Enquiry to the killings on Bloody Sunday in Londonderry in January 1972. I said I had no difficulty in understanding their desire to get to the bottom of these high-profile murders, which were widely laid at the feet of the security services working through loyalist proxies. And I would say as much, though I fear the party’s demands for a similar public enquiry will fall on deaf ears.

Weeks passed, and after Christmas I wrote again to the IRSP, pointing out my approaching deadline for completion of the book. I also telephoned regularly, not a simple procedure. Seamus Costello House is not Millbank or Central Office. Finally, I was given a number to contact in the Irish Republic. It was a mobile, not reachable from London. Further frustrating delays followed before I got through to a man I will refer to as Eoin. He told me to go to Belfast on the weekend of 24 March, and get in touch again on Friday 23rd. On Thursday, I received a message to call him again, and was redirected to Cork, hundreds of miles to the south in the Republic. It was too late to book a direct flight, so I continued via Belfast on the 23rd. Foot and mouth disease had just broken out in County Louth, slowing the train journey to Dublin, but I reached Cork in the early evening.

My instructions were to book into the Silver Springs Hotel, a modern establishment a few miles south of the city, and to await a call the following day. It was a bright, clear morning and the telephone rang at 9.30 a.m. I was to take a taxi to a country pub about five miles away, where I would be met. I waited in the lobby, self-consciously British in a dark suit and university tie. Just after 10.00 a.m., two men entered and motioned me into the bar. One was young, in his twenties, powerfully-built and dressed in waxed jacket and jeans. The other was much older, with white hair. Waxed-jacket said: ‘We will take you in the car. You will not look at the number plate. You will look down at the floor, not where we are going. Understand?’ I did. He then asked if I had a mobile phone, and I fished mine from a travel bag thinking he wished to use it. He confiscated the instrument.

Outside, he stood guard so I could not see the number plate. The older man drove, through various country lanes. It was difficult to obey the injunction to stare at the floor, but since I had no idea where we were it seemed superfluous anyway. We stopped outside an isolated house, quite high up, with hills around. I was escorted into the front room, where the thick curtains were drawn. Eoin, now that I saw him, looked like a schoolteacher in his late thirties: neat, spare and casually but well dressed. He introduced the man in the mask as ‘someone directly involved in the Neave operation’. I asked if I could take a shorthand note and he nodded. ‘You’re not wired?’ he interjected suddenly. ‘Open your shirt.’ I unbuttoned my shirt to the waist to show there was no hidden microphone. He frisked me, arms, back, front and legs. The tension eased somewhat, though I then spotted the handgun next to him. Had I done anything silly, I think it would have been used.

However, coffee and biscuits were served, as though we were discussing details of the Easter holidays rather than the brutal murder of a British politician two decades earlier. We spoke for two and a half hours, a mixture of questions and volunteered statements. The man in the mask, who displayed a very detailed knowledge of bomb-making and the modus operandi of the assassination, occasionally tugged at his uncomfortable camouflage. Eoin, the more intellectual of the two, ranged across the whole subject of INLA, the armed struggle and prospects for the future. It was a fascinating, if eerie, dialogue. What follows in Chapter 18 is a distillation of that briefing. I believe it to be the most authentic account yet of the circumstances of Airey Neave’s death. I expect that others may contest this assessment, but I am convinced that the IRSP/INLA deliberately gave this briefing to ensure that the truth is established, not least because they want the truth about the killing of their own.

At the close of the meeting, my mobile phone was returned, with the SIM card disabled so I could not be traced. The white-haired driver took me to a shopping centre, where I took a taxi back into Cork city to take the train to Dublin and Belfast. I drank a pint of Guinness at the station and pondered my experience. Instead of a reporter’s elation at finding my quarry, I felt a curious unease, as though I had discovered something I would rather not have known. Yet there was no going back, and I turned for home with a determination to get all this out. I hope the succeeding pages will demonstrate the virtue of seeking the truth, unpalatable though it may be. The Irish Question is never going to be solved by meek acceptance of the official line.

It should be added that this biography is not authorised, nor did I seek authorisation. Neave had written much about his own life, but his widow Diana rejected writers’ advances to sanction a biography of her husband. Patrick Cosgrave, a family friend, said she had asked him ‘to spread the word among the writing classes that she would, in no circumstances, countenance such a project’. Plainly, we do not move among the same writing classes because no such word reached these quarters.

However, I was able to speak to Neave’s children, Marigold, Patrick and William, for which I am grateful. I would also like to thank his cousin Julius Neave, of Mill Green House, Ingatestone. My gratitude also goes to Toni Luteyn, Neave’s co-escaper from Colditz, still alive and well in The Hague; to Frau Lipmann, curator of Colditz Museum; to the dedicated staff at the unrivalled political history collection at the Linen Hall Library for their help and advice; to the librarians at Eton College and Merton College, Oxford; to my colleagues in Westminster, especially Desmond McCartan, formerly of the Belfast Telegraph and David Healy of Bloomberg Agency; to Colin Wallace, Brian Crozier, Gerald James, Michael Elliott, Kevin Cahill, Roger Bolton, Richard Dumbreck, Sir Edward du Cann, Sir William Shelton, Tam Dalyell, Lord Lawton, Lord Campbell of Alloway, Ken Lockwood of the Colditz Association, Steven Norris, Kevin Macnamara MP, and those in London and Belfast who would be embarrassed (or worse) if identified; to Clive Priddle, Mitzi Angel and Kate Balmforth at Fourth Estate for their patience, and Richard Collins for his professional copy-editing; to my agent Jane Bradish-Ellames and finally to my wife Lynne for living with a political murder for too many years.

Walworth, south London

November 2001

1 The Price of Liberty

At 2.58 p.m. on 30 March 1979 an enormous explosion shook New Palace Yard in the precincts of the Palace of Westminster. Seconds later, smoke was seen billowing from the wreckage of a saloon car on the ramp leading up from the MPs’ car park into the cobbled courtyard just below Big Ben.

The blast was heard in the Commons chamber, where parliament was about to be dissolved for a General Election that would sweep Margaret Thatcher into Downing Street. Policemen and parliamentary journalists rushed to the scene and found an unidentifiable man, dressed in the black coat and striped trousers of an old-fashioned style still worn by Conservative MPs. David Healy, political correspondent of the Press Association news agency, was in the third-floor Press Gallery bar, whose back windows look down on New Palace Yard. A veteran reporter of the Irish Troubles, Healy recognised the familiar noise. ‘I knew it was a bomb,’ he said. ‘I looked out of the window and saw smoke, and rushed downstairs. The car was burning, the windows all broken. And this guy was almost blown into a standing position behind the wheel. A cop shouted, “He’s still alive! Clear the area!” I didn’t think there was much life left in him. I couldn’t tell who it was, though I had been having a drink with him only two nights earlier.’1 Another Westminster lobby correspondent, Desmond McCartan of the Belfast Telegraph, who knew the victim well, wrote: ‘The blackened, bleeding features amid the tangled wreckage of his Vauxhall car concealed his identity, but the pain of his dying was clear.’2

Ambulancemen who arrived within minutes found the still unidentified figure slumped over the driving wheel, his face blackened, his hair and clothing charred from the blast. His right leg was blown off below the knee, and his left leg was almost completely severed. One ambulanceman, Brian Craggs, tried to give him oxygen: ‘He was still breathing, but was very badly injured. He never regained consciousness.’ A doctor and nurse also attended, before he was freed after half an hour of frantic effort by firefighters.

Others had also recognised the noise. In Margaret Thatcher’s office, Chris Patten, a future Northern Ireland minister, exclaimed ‘That was a bomb!’ Thatcher’s entourage witnessed the grim scene from an upstairs window and Guinevere Tilney, wife of a former Tory MP and adviser to the Conservative leader, was the first to discover the identity of the victim. In the car, dying, lay Airey Neave, Conservative MP for Abingdon, war hero and habitué of the murky world where the politics of democracy and the secret state intertwine, the man who had engineered Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power. Mrs Tilney immediately went to the Neave family flat in Marsham Street to tell his wife Diana, and took her to Westminster Hospital where Neave was undergoing emergency surgery. The surgeons could do little. His heart stopped on the operating table and he died eight minutes after arriving at the hospital. His devoted wife was too late to see him alive.

It was a bloody end to a long career in public life, one marked in turn by disappointment and triumph ultimately crowned by Neave’s brilliant campaign to secure the Conservative Party leadership for Margaret Thatcher, an event that would radically change British – and international – politics. For his key role in that crusade, Neave was rewarded with the Shadow Cabinet portfolio that he coveted: Northern Ireland. It was a strange post to covet. Ulster has traditionally been regarded by pundits as a graveyard for political ambition, and Neave was fifty-nine when he took on the job in February 1975, having hitherto shown no serious public interest in the issue.

Nor did Neave look the part. Usually described as a slightly-built, red-faced man, with thinning hair, sharp features and a broad smile that rarely gave way to laughter, he moved with an almost feline grace, seeming to drift along rather than walk. He listened much, said little and when he did speak, he did so quietly. At a party given by Alan Clark, Thatcherite minister and diarist, George Gardiner, a right-wing Tory MP of the 1974 intake, listened to Neave ‘gently sounding out opinions in a voice you had to strain to hear’. Ian Aitken, political editor of the Guardian, found him ‘slightly sinister’. He was not particularly clubbable at Westminster though he was a member of the Special Services Club, tucked away in a side street behind Harrods where former and serving ‘spooks’ debated the follies of the world over cocktails.

The Troubles had been in full spate for several years by the time of his appointment, and showed no sign of abating. Shootings and bombings in the province were commonplace, and by taking Shadow Cabinet responsibility for British government policy he placed himself in the front line. It was almost as if the decorated war hero was inviting the bomb that prematurely ended his life. He told the journalist Patrick Cosgrave: ‘If they come for me, the one thing we can be sure of is that they will not face me. They’re not soldier enough for that.’3 His parliamentary agent Les Brown also claimed that Neave always knew he was on a death list, but realised it went with the territory. The writer Rebecca West had many years previously observed: ‘It is, I think, against his principles to care much about danger.’

Margaret Thatcher had no doubt that Neave was the right man for the job. ‘His intelligence contacts, proven physical courage and shrewdness amply qualified him for this testing and largely thankless task,’ she calculated.4 Her choice of priorities in this assessment is illuminating. She thought of him first as an expert in the field of military intelligence and only then as a man of nerve and astuteness. She did not immediately identify him as a politician with an agenda for bringing peace to the benighted province, where more than 247 people had died in the first year he was responsible for Opposition policy on Ulster. Her judgement was shared by Sir John Tilney, author of Neave’s entry in The Dictionary of National Biography. Working from ‘private information’, Tilney pointedly describes Neave as an ‘intelligence officer and politician’.

That Thatcher and Tilney should independently have come to the same conclusion should surprise no one, for Airey Neave was an intelligence officer who became a public servant. Like many who have trodden the same path, he did not slough off his first persona when he entered public life. The values of what has become known as ‘the secret state’, as well as the lessons of his wartime experiences, informed his outlook as a politician. He had many contacts among former security service officers and high-ranking army officers, and sympathised with the aims of the ultra-right groups that prepared for ‘civil breakdown’ in the 1970s. He was a public servant who never really stopped being a secret agent.

Neave’s background helped. His was a conformist, upper middle-class upbringing – prep school, Eton and Oxford, with a career at the Bar beckoning as the Second World War broke out. The son of a prominent entomologist and scion of an Essex county family whose lineage stretched back several hundred years (and included a Governor of the Bank of England), it was only to be expected that he would possess a relatively orthodox outlook on life. In Neave’s case, that sense of being British and right so endemic in his class was reinforced in his mid-teens when he was sent to Germany in 1933 to live with a local family and learn the language. He saw Fascism in practice, and formed a lifelong antipathy, amounting to an obsession, towards authoritarianism. Some of that feeling came from his pre-war and wartime adventures and filtered through a pessimistic fear of the spread of Communism that would harden during the Cold War and the civil unrest in Britain.

His initial links with the military were conventional enough, beginning when he enlisted in the Territorial Army as an undergraduate at Merton College. If Neave was swimming against the prevailing intellectual tide of leftism at university. His interest in the secretive world of Tory clubland politics also began at this period. He was a member of the Castlereagh Club, a political dining club that met in St James’s, Piccadilly, usually once a fortnight, to hear the views of a Tory dignitary. Donald Hamilton-Hill, later second in command of Special Operations Executive (SOE), the wartime resistance organisation, was also a member. In pre-war days he was chairman of public relations and head of recruiting for the Young Conservatives’ Union, and shared with Neave a predilection for the social contacts which ultimately led them into ‘politically informative circles’. Confidentiality, if not mystery, was the order of the day. Hamilton-Hill recorded that members of the Castlereagh Club held ‘off the record and interesting discussions – with no reporters present and members sworn to secrecy’. After a ‘splendid dinner’ they formed an easy and appreciative friendship over port, brandy and cigars.5 For the young Neave, it was heady and exciting stuff, and plainly a taste for secrecy and subterfuge was being acquired early. One of their mentors was Ronnie Cartland, a Tory MP who would be killed at Dunkirk; Peter Wilkinson, who went on to General de Wiart’s staff of the British Military Mission to Poland in 1939, was also a member. He later became Chief of Administration of the Diplomatic Service, and retired in 1976 as Coordinator of Intelligence and Security in the Cabinet Office. Val Duncan, subsequently knighted and chairman of the Rio Tinto Zinc Corporation, was also to be found at the Castlereagh table. In the late sixties, he would head an enquiry into the Foreign Office at Wilkinson’s behest.

Quite why the enthusiastic diners chose an Irish grandee as the club’s eponymous hero is unclear, but in Neave’s case it was prophetic. Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, was born in Dublin in 1769 and became Tory MP for County Down at the end of the eighteenth century. He was appointed Irish Secretary in 1797 and his name became a byword for cruelty, although he was venerated as a great British statesman. In ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ of 1819, Shelley was prompted to write: ‘I met Murder on the Way / He had a mask like Castlereagh’. Almost two hundred years later, his name was remembered in the British government’s Castlereagh interrogation centre in Belfast, itself the subject of an enquiry into Royal Ulster Constabulary brutality during Neave’s time as Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary. Thus was Neave drawn early on into the demi-monde of clubland, where politics meets the secret state. Security and intelligence expert Stephen Dorril argues its relevance: ‘This is the key to the way these people operate. Their dining clubs go on for a long time. They are the networks of political power and advancement. They bring all the elements of the secret state together.’6