Полная версия:

Carve the Mark

First published in the US by Katherine Tegen Books in 2017

Katherine Tegen Books is an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

Published in this edition in 2018

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Text copyright © Veronica Roth 2017

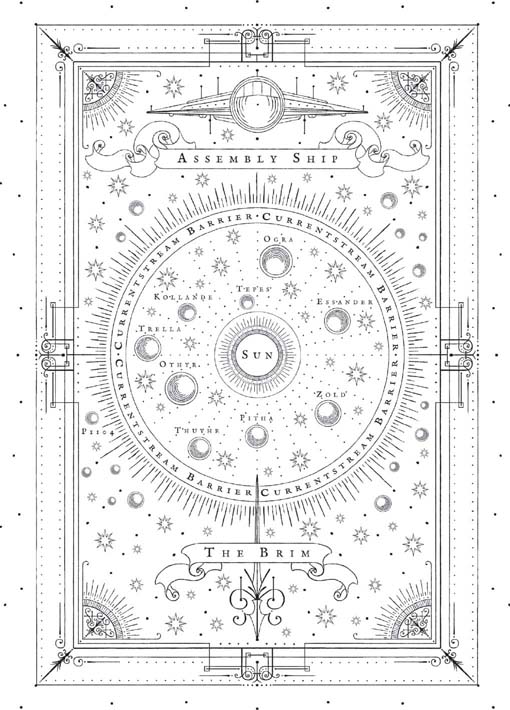

Map copyright © Veronica Roth 2017

Map illustrated by Virginia Allyn

Jacket art ™ & © 2017 by Veronica Roth

Jacket art by Jeff Huang

Jacket design by Joel Tippie

Veronica Roth asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008159498

Ebook Edition © 2018 ISBN: 9780008159504

Version: 2018-01-25

ADDITIONAL PRAISE FOR

CARVE THE MARK

#1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

#1 INDIEBOUND YOUNG ADULT BESTSELLER

#1 PUBLISHERS WEEKLY CHILDREN’S BESTSELLER

WALL STREET JOURNAL BESTSELLER

USA TODAY BESTSELLER

“Roth skillfully weaves the careful world-building and intricate web of characters that distinguished Divergent, with settings that are rich with color, ripe for a cinematographer. Roth fans will cheer this new novel with its power to absorb the reader. Readers will be anxiously awaiting the sequel.”

—VOYA (starred review)

“Brimming with plot twists and highly likely to please Roth’s fans.”

—KIRKUS REVIEWS

“Roth offers a richly imagined, often-brutal world of political intrigue and adventure, with a slow-burning romance at its core. Roth’s fans will be happily on board for the forthcoming sequel.”

—ALA BOOKLIST

“Roth’s world-building is commendable; each nation is distinct, interacting with the current in ways that give insight into her characters’ motivations. Amid political machinations and forays into space, Roth thoughtfully addresses substantial issues, such as the power of self-determination in the face of fate. Readers will eagerly await a second installment.”

—PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“The Divergent author builds out this new world—one reminiscent of Star Wars, with its discussions of ‘the current’ and ‘currentgifts’—while still presenting the stark brutality of the circumstances both protagonists find themselves in.”

—ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY

“This duology offers shades of George Lucas sprawl and influence, Game of Thrones clan intrigue, and a little Romeo and Juliet–style romance. There are cliffhangers aplenty and dangling plot lines to lure us to the next book.”

—USA TODAY

To Ingrid and Karl—

because there is no version of you I don’t love

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Part 1

Chapter 1: Akos

Chapter 2: Akos

Part 2

Chapter 3: Cyra

Chapter 4: Cyra

Chapter 5: Cyra

Chapter 6: Cyra

Chapter 7: Cyra

Chapter 8: Cyra

Chapter 9: Cyra

Chapter 10: Cyra

Chapter 11: Cyra

Chapter 12: Cyra

Chapter 13: Cyra

Chapter 14: Cyra

Part 3

Chapter 15: Akos

Chapter 16: Cyra

Chapter 17: Akos

Chapter 18: Cyra

Chapter 19: Akos

Chapter 20: Cyra

Chapter 21: Akos

Chapter 22: Cyra

Chapter 23: Akos

Chapter 24: Cyra

Chapter 25: Cyra

Part 4

Chapter 26: Akos

Chapter 27: Akos

Chapter 28: Akos

Chapter 29: Cyra

Chapter 30: Akos

Chapter 31: Cyra

Chapter 32: Akos

Chapter 33: Cyra

Chapter 34: Akos

Chapter 35: Cyra

Chapter 36: Akos

Chapter 37: Cyra

Chapter 38: Akos

Chapter 39: Cyra

Chapter 40: Akos

Chapter 41: Cyra

Chapter 42: Akos

Glossary

Acknowledgments

Read on for the Divergent Epilogue: We Can Be Mended

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Books by Veronica Roth

About the Publisher

HUSHFLOWERS ALWAYS BLOOMED WHEN the night was longest. The whole city celebrated the day the bundle of petals peeled apart into rich red—partly because hushflowers were their nation’s lifeblood, and partly, Akos thought, to keep them all from going crazy in the cold.

That evening, on the day of the Blooming ritual, he was sweating into his coat as he waited for the rest of the family to be ready, so he went out to the courtyard to cool off. The Kereseth house was built in a circle around a furnace, all the outermost and innermost walls curved. For luck, supposedly.

Frozen air stung his eyes when he opened the door. He yanked his goggles down, and the heat from his skin fogged up the glass right away. He fumbled for the metal poker with his gloved hand and stuck it under the furnace hood. The burnstones under it just looked like black lumps before friction lit them, and then they sparked in different colors, depending on what they were dusted with.

The burnstones scraped together and lit up bright red as blood. They weren’t out here to warm anything, or light anything—they were just supposed to be a reminder of the current. As if the hum in Akos’s body wasn’t enough of a reminder. The current flowed through every living thing, and showed itself in the sky in all different colors. Like the burnstones. Like the lights of the floaters that zoomed overhead on their way to town proper. Off-worlders who thought their planet was blank with snow had never actually set foot on it.

Akos’s older brother, Eijeh, poked his head out. “Eager to freeze, are you? Come on, Mom’s nearly ready.”

It always took their mom longer to get ready when they were going to the temple. After all, she was the oracle. Everybody would be staring right at her.

Akos put the poker down and stepped inside, popping the goggles off his eyes and pulling his face shield down to his throat.

His dad and his older sister, Cisi, were standing by the front door, stuffed into their warmest coats. They were all made of the same material—kutyah fur, which didn’t take dye, so it was always white gray—and hooded.

“All ready then, Akos? Good.” His mom was fastening her own coat closed. She eyed their dad’s old boots. “Somewhere out there, your father’s ashes are collectively shuddering at how dirty your shoes are, Aoseh.”

“I know, that’s why I fussed about dirtying them up,” their dad said with a grin at their mom.

“Good,” she said. Almost chirped it, in fact. “I like them this way.”

“You like anything my father didn’t like.”

“That’s because he didn’t like anything.”

“Can we get into the floater while it’s still warm?” Eijeh said, a little bit of a whine in his voice. “Ori’s waiting for us by the memorial.”

Their mom finished with her coat, and put on her face shield. Down the heated front walk they bobbed, all fur and goggle and mitten. A squat, round ship waited for them, hovering at knee height just above the snowbank. The door opened at their mom’s touch and they piled in. Cisi and Eijeh had to yank Akos in by both arms because he was too small to climb on his own. Nobody bothered with safety belts.

“To the temple!” their dad cried, his fist in the air. He always said that when they went to the temple. Sort of like cheering for a boring lecture or a long line on voting day.

“If only we could bottle that excitement and sell it to all of Thuvhe. Most of them I see just once a year, and then only because there’s food and drink waiting for them,” their mom drawled with a faint smile.

“There’s your solution, then,” Eijeh said. “Entice them with food all season long.”

“The wisdom of children,” their mom said, poking the ignition button with her thumb.

The floater jerked them up and forward, so they all fell into each other. Eijeh punched Akos away from him, laughing.

The lights of Hessa twinkled up ahead. Their city wrapped around a hill, the military base at the bottom, the temple at the top, and all the other buildings in between. The temple, where they were headed, was a big stone structure with a dome—made of hundreds of panes of colored glass—right in the middle of it. When the sun shone on it, Hessa’s peak glowed orange red. Which meant it almost never glowed.

The floater eased up the hill, drifting over stony Hessa, as old as their nation-planet—Thuvhe, as everyone but their enemies called it, a word so slippery off-worlders tended to choke on it. Half the narrow houses were buried in snowdrifts. Nearly all of them were empty. Everybody who was anybody was going to the temple tonight.

“See anything interesting today?” their dad asked their mom as he steered the floater away from a particularly tall windmeter poking up into the sky. It was spinning in circles.

Akos knew by the tone of his dad’s voice that he was asking their mom about her visions. Every planet in the galaxy had three oracles: one rising; one sitting, like their mother; and one falling. Akos didn’t quite understand what it meant, except that the current whispered the future in his mom’s ears, and half the people they came across were in awe of her.

“I may have spotted your sister the other day—” their mom started. “Doubt she’d want to know, though.”

“She just feels the future ought to be handled with the appropriate respect for its weight.”

Their mom’s eyes swept over Akos, Eijeh, and Cisi in turn.

“This is what I get for marrying into a military family, I guess,” she said eventually. “You want everything to be regulated, even my currentgift.”

“You’ll notice that I flew in the face of family expectation and chose to be a farmer, not a military captain,” their dad said. “And my sister doesn’t mean anything by it, she just gets nervous, that’s all.”

“Hmm,” their mom said, like that wasn’t all.

Cisi started humming, a melody Akos had heard before, but couldn’t say from where. His sister was looking out the window, not paying attention to the bickering. And a few ticks later, his parents’ bickering stopped, and the sound of her hum was all that was left. Cisi had a way about her, their dad liked to say. An ease.

The temple was lit up, inside and out, strings of lanterns no bigger than Akos’s fist hanging over the arched entrance. There were floaters everywhere, strips of colored light wrapped around their fat bellies, parked in clusters on the hillside or swarming around the domed roof in search of a space to touch down. Their mom knew all the secret places around the temple, so she pointed their dad toward a shadowed nook next to the refectory, and led them in a sprint to a side door that she had to pry open with both hands.

They went down a dark stone hallway, over rugs so worn you could see right through them, and past the low, candlelit memorial for the Thuvhesits who had died in the Shotet invasion, before Akos was born.

He slowed to look at the flickering candles as he passed the memorial. Eijeh grabbed his shoulders from behind, making Akos gasp, startled. He blushed as soon as he realized who it was, and Eijeh poked his cheek, laughing, “I can tell how red you are even in the dark!”

“Shut up!” Akos said.

“Eijeh,” their mom chided. “Don’t tease.”

She had to say it all the time. Akos felt like he was always blushing about something.

“It was just a joke. …”

They found their way to the middle of the building, where a crowd had formed outside the Hall of Prophecy. Everyone was stomping their way out of their outer boots, shrugging off coats, fluffing hair that had been flattened by hoods, breathing warm air on frozen fingers. The Kereseths piled their coats, goggles, mittens, boots, and face coverings in a dark alcove, right under a purple window with the Thuvhesit character for the current etched into it. Just as they were turning back to the Hall of Prophecy, Akos heard a familiar voice.

“Eij!” Ori Rednalis, Eijeh’s best friend, came barreling down the hallway. She was gangly and clumsy-looking, all knees and elbows and stray hair. Akos had never seen her in a dress before, but she was in one now, made of heavy purple-red fabric and buttoned at the shoulder like a formal military uniform.

Ori’s knuckles were red with cold. She jumped to a stop in front of Eijeh. “There you are. I’ve had to listen to two of my aunt’s rants about the Assembly already and I’m about to explode.” Akos had heard one of Ori’s aunt’s rants before, about the Assembly—the governing body of the galaxy—valuing Thuvhe only for its iceflower production, and downplaying the Shotet attacks, calling them “civil disputes.” She had a point, but Akos always felt squirmy around ranting adults. He never knew what to say.

Ori continued, “Hello, Aoseh, Sifa, Cisi, Akos. Happy Blooming. Come on, let’s go, Eij.” She said all this in one go, hardly taking the time to breathe.

Eijeh looked to their dad, who flapped his hand. “Go on, then. We’ll see you later.”

“And if we catch you with a pipe in your mouth, as we did last year,” their mom said, “we will make you eat what’s inside it.”

Eijeh quirked his eyebrows. He never got embarrassed about anything, never flushed. Not even when the kids at school teased him for his voice—higher than most boys’—or for being rich, not something that made a person popular here in Hessa. He didn’t snap back, either. Just had a gift for shutting things out and letting them back in only when he wanted to.

He grabbed Akos by the elbow and pulled him after Ori. Cisi stayed behind, with their parents, like always. Eijeh and Akos chased Ori’s heels all the way into the Hall of Prophecy.

Ori gasped, and when Akos saw inside the hall, he almost echoed her. Somebody had strung hundreds of lanterns—each one dusted with hushflower to make it red—from the apex of the dome down to the outermost walls, in every direction, so a canopy of light hung over them. Even Eijeh’s teeth glowed red, when he grinned at Akos. In the middle of the room, which was usually empty, was a sheet of ice about as wide as a man was tall. Growing inside it were dozens of closed-up hushflowers on the verge of blooming.

More burnstone lanterns, about as big as Akos’s thumb, lined the sheet of ice where the hushflowers waited to bloom. These glowed white, probably so everyone could see the hushflowers’ true color, a richer red than any lantern. As rich as blood, some said.

There were a lot of people milling about, dressed in their finery: loose gowns that covered all but the hands and head, fastened with elaborate glass buttons in all different colors; knee-length waistcoats lined with supple elte skin, and twice-wrapped scarves. All in dark, rich colors, anything but gray or white, in contrast to their coats. Akos’s jacket was dark green, one of Eijeh’s old ones, still too big in the shoulders for him, and Eijeh’s was brown.

Ori led the way straight to the food. Her sour-faced aunt was there, offering plates to passersby, but she didn’t look at Ori. Akos got the feeling Ori didn’t like her aunt and uncle, which was why she pretty much lived at the Kereseth house, but he didn’t know what had happened to her parents.

Eijeh stuffed a roll in his mouth, practically choking on the crumbs.

“Careful,” Akos said to him. “Death by bread isn’t a dignified way to go.”

“At least I’ll die doing what I love,” Eijeh said, around all the bread.

Akos laughed.

Ori hooked her elbow around Eijeh’s neck, tugging his head in close. “Don’t look now. Stares coming in from the left.”

“So?” Eijeh said, spraying crumbs. But Akos already felt heat creeping into his neck. He chanced a look over at Eijeh’s left. A little group of adults stood there, quiet, eyes following them.

“You’d think you’d be a little more used to it, Akos,” Eijeh said to him. “Happens all the time, after all.”

“You’d think they would be used to us,” Akos said. “We’ve lived here all our lives, and we’ve had fates all our lives, what’s there to stare at?”

Everyone had a future, but not everyone had a fate—at least, that was what their mom liked to say. Only parts of certain “favored” families got fates, witnessed at the moment of their births by every oracle on every planet. In unison. When those visions came, their mom said, they could wake her from a sound sleep, they were so forceful.

Eijeh, Cisi, and Akos had fates. Only they didn’t know what they were, even though their mom was one of the people who had Seen them. She always said she didn’t need to tell them; the world would do it for her.

The fates were supposed to determine the movements of the worlds. If Akos thought about that too long, he got nauseous.

Ori shrugged. “My aunt says the Assembly’s been critical of the oracles on the news feed lately, so it’s probably just on everyone’s minds.”

“Critical?” Akos said. “Why?”

Eijeh ignored them both. “Come on, let’s find a good spot.”

Ori brightened. “Yeah, let’s. I don’t want to get stuck staring at other people’s butts like last year.”

“I think you’ve grown past butt height this year,” Eijeh said. “Now you’re at mid-back, maybe.”

“Oh good, because I definitely put on this dress for my aunt so I could stare at a bunch of backs.” Ori rolled her eyes.

This time Akos slipped into the crowd in the Hall of Prophecy first, ducking under glasses of wine and swooping gestures until he got to the front, right by the ice sheet and the closed-up hushflowers. They were right on time, too—their mom was up by the ice sheet, and she had taken off her shoes, though it was chilly in here. She said she was better at being an oracle when she was closer to the ground.

A few ticks ago he’d been laughing with Eijeh, but as the crowd went quiet, everything in Akos went quiet, too.

Eijeh leaned in close to him and whispered in his ear, “Do you feel that? The current’s humming like crazy in here. It’s like my chest is vibrating.”

Akos hadn’t noticed it, but Eijeh was right—he did feel like his chest was vibrating, like his blood was singing. Before he could answer, though, their mom started talking. Not loud, but she didn’t have to be, because they all knew the words by heart.

“The current flows through every planet in the galaxy, giving us its light as a reminder of its power.” As if on cue, they all looked up at the currentstream, its light showing in the sky through the red glass of the dome. At this time of year, it was almost always dark red, just like the hushflowers, like the glass itself. The currentstream was the visible sign of the current that flowed through all of them, and every living thing. It wound across the galaxy, binding all the planets together like beads on a single string.

“The current flows through everything that has life,” Sifa went on, “creating a space for it to thrive. The current flows through every person who breathes breath, and emerges differently through each mind’s sieve. The current flows through every flower that blooms in the ice.”

They scrunched together—not just Akos and Eijeh and Ori, but everyone in the whole room, standing shoulder to shoulder, so they could all see what was happening to the hushflowers in the ice sheet.

“The current flows through every flower that blooms in the ice,” Sifa repeated, “giving them the strength to bloom in the deepest dark. The current gives the most strength to the hushflower, our marker of time, our death-giving and peace-giving blossom.”

For a while there was silence, and it didn’t feel odd, like it should have. It was as if they were all hum-buzz-singing together, feeling the strange force that powered their universe, just like friction between particles powered the burnstones.

And then—movement. A shifting petal. A creaking stem. A shudder went through the small field of hushflowers growing among them. No one made a sound.

Akos glanced up at the red glass, the canopy of lanterns, just once, and he almost missed it—all the flowers bursting open. Red petals unfurling all at once, showing their bright centers, draping over their stems. The ice sheet teemed with color.

Everyone gasped, and applauded. Akos clapped with the rest of them, until his palms itched. Their dad came up to take their mom’s hands and plant a kiss on her. To everyone else she was untouchable: Sifa Kereseth, the oracle, the one whose currentgift gave her visions of the future. But their dad was always touching her, pressing the tip of his finger into her dimple when she smiled, tucking strays back into the knot she wore her hair in, leaving yellow flour fingerprints on her shoulders when he was done kneading the bread.

Their dad couldn’t see the future, but he could mend things with his fingers, like broken plates or the crack in the wall screen or the frayed hem of an old shirt. Sometimes he made you feel like he could put people back together, too, if they got themselves into trouble. So when he walked over to Akos, swung him into his arms, Akos didn’t even get embarrassed.

“Smallest Child!” his dad cried, tossing Akos over his shoulder. “Ooh—not so small, actually. Almost can’t do this anymore.”

“That’s not because I’m big, it’s because you’re old,” Akos replied.

“Such words! From my own son,” his dad said. “What punishment does a sharp tongue like that deserve, I wonder?”

“Don’t—”

But it was too late; his dad had already pitched him back and let him slide so he was holding both of Akos’s ankles. Hanging upside down, Akos pressed his shirt and jacket to his body, but he couldn’t help laughing. Aoseh lowered him down, only letting go when Akos was safe on the ground.