Полная версия:

Big Fry: Barry Fry: The Autobiography

Copyright

Harper Non-Fiction

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in 2000 by CollinsWillow

First published in paperback 2001

© Barry Fry Promotions Ltd 2001

Barry Fry and Phil Rostron asserts the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780002189491

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2016 ISBN: 9780007483297

Version: 2016-09-09

Dedication

To my wife Kirstine,

and my children Jane, Mark, Adam,

Amber, Frank and Anna-Marie.

Contents

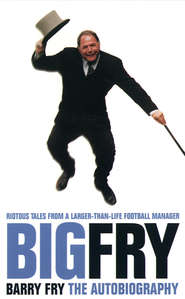

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Sir Alex Ferguson

ONE Who’d be a football manager?

TWO ‘Practice son, practice’

THREE New boy at Old Trafford

FOUR Bankruptcy and on the scrapheap

FIVE Cheeseman and the frilly knickers

SIX Backs to the wall at Barnet

SEVEN Stan the Main Man

EIGHT ‘You won’t be alive to pick the team’

NINE Fry in, Collymore out

TEN Brady blues

ELEVEN ‘How many caps does that woman wear here?’

TWELVE Over to you, Trevor

THIRTEEN Posh but pricey

FOURTEEN A small matter of £3.1 million

FIFTEEN Saved by the Pizzaman

SIXTEEN Play-offs, promotion and ponces

SEVENTEEN Competing with the Big Boys

EIGHTEEN Small Fry

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been possible but for the support of my family. To my late mum Dora and dad Frank, thanks for all the sacrifices you made for me and your encouragement and understanding in trying to help me fulfil my dream. My wife Kirstine has been a rock, my best ever signing, while her mum Gisela and dad Andy have always been there for me.

I was fortunate enough to be at the birth of each of my six children Jane, Mark, Adam, Amber, Frank and Anna-Marie, and I can honestly say that the experience is better than scoring at Wembley! Since the days they were born they have all, in different ways, brought so much pleasure and enjoyment into my life. As have my three grand-children Keeley-Anne, Yasmin and Louis and the best son-in-law anybody could wish for in Steve. I count my lucky stars that I have been surrounded by such a wonderful group of family and friends through my rollercoaster career in football.

Finally, thanks to my publishers HarperCollins and the man who helped me put my thoughts down in writing, Phil Rostron. It’s been a privilege working with such professionals.

FOREWORD

Sir Alex Ferguson

I am privileged to have been asked to write the foreword to the autobiography of a man whom I cannot bring to mind without the thought prompting a smile. This is not because Barry Fry is a figure of fun, but because of his larger-than-life character, happy-go-lucky nature and reliance upon humour to soften the blows which a life in football can inflict with uncomfortable regularity.

Barry is a man for whom football is a blinding passion, displayed in his every thought, word and deed. He is one of the rare birds in the game in that he is highly respected by almost all of his fellow professionals for his vast knowledge, unquenchable enthusiasm and unflinching adherence to the ideals in which he believes.

He is a very popular manager among managers. Barry may not have been at the helm of a Premiership club but that, in itself, is surprising in many ways because he has achieved success in one way or another at each of the many he has managed both in non-league football and in the lower divisions of the Football League.

A staunch member of the League Managers’ Association, he shows as much enthusiasm for its affairs as he does in his day-to-day club involvement. We operate in an industry which all too often does not meet its obligations when there is a parting of the ways between clubs and managers, and there is a real need for voices as powerful as Barry’s to be heard if an equilibrium is to be achieved. Some managers are fortunate enough to walk straight into another job once they have been shown the door, but there are many others who do not enjoy the same fortune for one reason or another. They need protection, with due and full severance pay a priority, and Barry, who knows a thing or two about such matters, works tirelessly towards these goals.

Thoughts for the welfare of others are typical of the man and his self-deprecation is very endearing. Having walked into Old Trafford as a young boy to become one of the original Busby Babes, he says that the only reason Barry Fry did not make it as a player was Barry Fry. He is perhaps being a little hard on himself with this observation. The fact is that the crop of youngsters with whom he was competing for places at the time was exceptional, as has regularly been the case at Manchester United, and it is no disgrace that he failed to break through into the big time.

There is no disputing that he was a smashing little player – you don’t get schoolboy international caps and headhunted by Manchester United if you are no good – but Barry didn’t get the breaks. Simple as that.

An incongruity in football is the number of great players who do not aspire to be, nor become, top managers and a corresponding number of distinctly average players who achieve tremendous managerial success. In my own case I was never anything more than a run-of-the-mill player and the same could be said of the likes of Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley, but playing is one thing and managing entirely another. Barry is in the category of people who have done better as the man in charge than he did as the one taking the orders and his feats in winning championships and cup competitions are not to be underestimated. In any walk of life you have to be special to achieve success and there is no doubt that Barry Fry is a very special man.

He takes us here on a roller-coaster ride which reflects his colourful life. Hold on to your hats and enjoy the journey. Then, when you think about Barry Fry in the future, I defy you to do so without a smile on your face.

CHAPTER ONE

Who’d be a football manager?

Raindrops trickled down the window of the prefabricated building that was my office on the winter’s day that a familiar red Lamborghini drew to a halt in the parking bay outside. The magnificent machine was just one of the success symbols flaunted by the highly charismatic Keith Cheeseman, who had recently assumed control of the Southern League club Dunstable Town. This was my first managerial position in football and I felt privileged to be the individual charged with the task of transforming the fortunes of a club which, for eight successive seasons, had finished stone cold bottom of the league. I was in a fairly strong position in that things could hardly have got worse. Or so it seemed.

I was just a few months into the job and the chairman’s arrival on this dank Tuesday was the signal that this was to be no ordinary day. Up until now he had never been near the ground in midweek unless we had a game. And even then he did not come to all the games because he got bored with them.

My first thought as he got out of the car was ‘What the hell is he doing here?’

As he came into my office I offered him a warm greeting.

‘Hello mate, what brings you here?’

He replied that he had come to meet somebody and seemed disappointed when I said that nobody had arrived.

I offered him a cup of tea, which he rejected, and he waved aside my invitation to sit down. He was on edge and started to prowl the room. Even though he was always naturally on the go, there was something different about his demeanour.

After a while a Jaguar pulled up alongside the Lamborghini, giving this dilapidated little outreach in Bedfordshire the incongruous appearance of a classic car showroom. We watched as the driver emerged and walked to my office. His polite knock on the door was answered by Cheeseman.

‘Ah, I’ve been waiting for you.’

‘I’m Keith Cheeseman. Please come in.’

And with that greeting the chairman slammed the door shut. In a lightning-fast move he had his visitor pinned back against the door with his forearm tight against his throat. He hastily frisked this hapless man and, as I recoiled in horror, Cheeseman tried to make light of the situation.

‘Just checking that you aren’t bugged or carrying a gun,’ he laughed.

Now I’m just a silly football manager and I feared something approaching a siege might be developing, but Cheeseman just said: ‘Barry, I’ve got to speak privately to this man. Have you got the keys to the boardroom?’

Confirming that they were in my car, I went to get them as they made their way to the boardroom at the other side of the ground. I caught up with them and as they stood on the halfway line they surveyed an advertising hoarding belonging to a particular finance company.

I was never introduced to the visitor, who boomed at the chairman: ‘You can take that board down straight away. That goes for starters.’

Cheeseman put his arm round him and smiled.

‘My boy, that’s just cost you three quarters of a million. I’d leave it there if I were you.’

And with that I let them into the boardroom where, I presumed, they concluded whatever business they were up to. None of what had happened and been said made any sense to me but I was left with the distinct impression that something was amiss.

A few days later I was given a much bigger indication of the type of man I was working for. We had a home game on the Tuesday night and in the afternoon I took a call from Cheeseman in which he said that he would not be going to the match. I said that was fair enough, but there was more. He said that after the game he wanted me to do him a favour and go to meet him.

‘I’m only in the country for five minutes,’ he said ‘but I want to see you before I go. I’ll ring you when the match is over and let you know the location.’

I didn’t raise an eyebrow because it was not unusual for him to be abroad on business. I often went to his office in Luton before one of these trips for him to hand over some cash or to sign some cheques.

When his telephone call came there was something quite sinister about it.

‘Right,’ he said, ‘I want you to leave and bring with you a case that somebody has dropped at the ground during the game. When you get to the roundabout at Houghton Regis go round it two or three times and make absolutely sure that you are not being followed. Then shoot off all the way down the A5, get on the M1 at the end and come off at Scratchwood Services. I will meet you there.’

‘Keith, what the hell …’

‘I’ll explain it all when you get here,’ he interjected. ‘Just make sure you have got the bag.’

I asked the secretary, Harold Stew, whether someone had dropped off a bag from the chairman’s office and he confirmed that it was in one of the other offices. So I picked up this big bag, a briefcase, and put it in the boot of my car.

It was with a very nervous look into my rear mirror that I pulled away from the ground and onto my unscheduled journey. I approached the Houghton Regis roundabout with his words ringing in my ears, but I just thought how ridiculous it would be to keep going round and round it and completed the manoeuvre normally. From there, though, I could hardly keep my eyes on the road ahead because I was looking so many times into the mirrors. It was frightening how often I thought one car, then another, then another was tailing me. Paranoia was sweeping over me.

I was overcome with a sense of relief as I arrived unscathed at Scratchwood, yet there was still a feeling of foreboding about the contents of the case and what kind of situation I might soon be walking in to.

Cheeseman answered my knock at the door and welcomed me into a room inhabited by two other members of the finance company and three other people who acted as legal representatives and advisers.

As well as being a member of the Dunstable Football Club board, one was also the manager of the finance house. I hadn’t seen him for some time and greeted him warmly. But when I asked if he was well he answered: ‘Oh, I’m terrible. I’ve been out to Keith’s place in Spain and all hell has broken loose.’

Cheeseman broke in here and asked me, ‘Have you got the case?’

‘Oh yes, I forgot. It’s in the boot of my car.’ He asked for the keys and off he went to get it.

His exit allowed a resumption of my chat with the pale-faced money manager.

‘We’ve got some problems. I’ve got to get out of the country.’

I pointed out that he had just been abroad.

‘I know,’ he replied, ‘but I’ve got to go again and for longer this time.’

Cheeseman returned with the case, put it on one of the beds and threw it open. Well, I have never seen such money in all my life. It was crammed full of foreign notes amounting to goodness knows how much.

‘What the hell’s going on?’ I asked the chairman nervously.

‘I’ll tell you later. We have just got to look after him now.’

Trying to lift the atmosphere I asked if anyone was having tea or coffee or a beer, but Cheeseman said abruptly: ‘No. You can go back now.’

‘But I thought you wanted to see me?’

‘No, I only wanted this,’ he said pointing to the money.

I left more than a little concerned. I was 28 years old, terribly naive in the ways of the business world, desperate to make an impression in my first job in football management as a player-manager and here I was, witnessing twice within the space of a week, some very suspicious activities involving the very person I should be able to rely upon for all kinds of things, my chairman.

I drove home stony-faced and with my head swimming. I thought about what had gone before with Cheeseman and things slowly began to add up.

There was, for instance, the Jeff Astle fiasco. This man had been a legend in his time at West Bromwich Albion and it was considered a fantastic coup when I signed him for Dunstable. The ultimate professional, he had been working for Cheeseman’s building firm in the Mid-lands and after two months he came to me and said that he didn’t like the situation of living and working such a distance from the club.

Keith urged him to move south, pointing out that he was selling his home in Clophill and moving to a mansion in Houghton Regis. It might be an agreeable solution if Astle were to buy his house.

It was an amicable arrangement for Jeff, too, and he moved in. It was not long, though, before he started to come to see me and say: ‘I still haven’t got the deeds to that house, Baz. What am I going to do?’

At the end of that season and the beginning of the next campaign – Jeff had scored 34 goals for me – I had had my first blazing row with the chairman. Jeff found out that on the property in Clophill there were no fewer than 35 mortgages that had never been paid. He didn’t get the deeds because they were never Cheeseman’s to give. There had been this second mortgage and that second mortgage. How the hell Keith managed it, I don’t know.

Jeff told me this and I said that if that were the case then he could go. Graham Carr, the Weymouth manager, had wanted to buy him and offered £15,000, but I said that if Cheeseman had done him out of any money, then as far as I was concerned he could go for nothing and get himself looked after in terms of a signing-on fee and any other inducements.

The mortgages totalled £200,000 on a house Jeff thought he had bought for £14,000. I let Jeff and his wife Larraine go to Weymouth for talks with the intention of trying to sort out the mortgage situation. But when I mentioned it to Cheeseman he just huffed and puffed and bluffed and blamed it on anybody and everybody else. He told Jeff everything would be all right but the player himself was far from convinced and I sold Jeff to Weymouth so that he could get back at least some of the money that he had forked out. Nowhere near the full amount, but some of it at least.

He went reluctantly because he was happy playing for Dunstable and was a great hero with the fans. No doubt prompted by Jeff’s displeasure at the house situation Cheeseman came to see me one day.

‘This Astle … he ain’t doing this, he ain’t doing that, he ain’t doing f**k all,’ he blasted.

But I stopped him in his tracks.

‘Keith, I’ve sold him.’

‘You’ve what?’ he screamed.

We were on the pitch and he’s a bloody big geezer and we were face-to-face snarling. I’ve never seen a man so consumed with anger. Knowing what I know now, I was bloody lucky to get away with what I said to him next.

‘You don’t f***ing treat my players like that. You’d better treat my players right because if you f**k them up like that, mate, I’m no longer with you. My loyalty is to my players. I’ve sold him, he’s gone and there’s f**k all you can do about it.’

I was sure he would sack me after this tirade, but he didn’t. Yet Jeff had gone, which was heartbreaking. This episode had brought on further inclinations that things were not quite right at the club. Yet Keith was never around. He was always in Australia, America, Tenerife, London, the West Midlands. So rarely in his office in Luton and even more infrequently at the club.

From another perspective, it was great. He would ring every now and then but, by and large, he didn’t bother me. As long as the club was ticking over he remained in the background. He just paid the bills and if I saw him and needed money he would leave me readies, otherwise he would leave a sheaf of cheques, sign the lot and leave it to me to pay what had to be paid. This, at least, was on the playing side. All the other bills went to Betty and Harold in the general office and I never saw them.

It was a deeply worrying time and what I was considering more and more to be the inevitable happened one day when the police arrived on the scene.

I was full time on my own at Dunstable, even running the lotteries. Jeff used to help me sell the tickets and he became a great PR man for the club, but I faced the police alone as one officer began to ask questions like ‘Have you got a second mortgage on your property?’ and ‘Have you ever dealt with this finance company?’

As their line of questioning unfolded I began to put two and two together.

I remembered the last Christmas party. Cheeseman had the generosity to invite not only the players, but their wives, girlfriends, parents, family, Uncle Tom Cobley and all. I could not fathom this, nor his wanting all their names and addresses. It was almost on the scale of the party he threw at Caesar’s Palace, Luton – for the entire Southern League!

All the players had loans. All their parents had loans. The names and addresses were not to be invited to a party, they were to be the subjects of loans. It was a genius idea. Brilliant. A great scam, and it would have worked. Keith had all the money coming in, but he was greedy, always wanting to go off at tangents and bring in this, that and the other. He wanted to go out and buy a nightclub with George Best, for instance. All hell broke loose and he was arrested. I couldn’t find him. Nobody could find him. We didn’t know what was going on, but then everything came out of the woodwork. Every five minutes it seemed there was a knock at the club door.

‘You owe me ten grand.’

‘You owe me fifteen grand …’

‘I did that building work and I haven’t been paid.’

‘I did the floodlight work. You haven’t paid me.’

‘You owe Caesar’s Palace for that big party.’

All of a sudden, a club going along nicely, top of the Southern League, are in deep trouble. Our man, whom we can’t find, owns the club lock, stock and barrel. The only thing I can do is to sell players. I had to sell Lou Adams, George Cleary, Terry Mortimer; Astle had already gone. I had to sell anybody I could. The lads didn’t have any wages and we didn’t have a penny in the bank. Cheeseman always paid us in readies. So in my second year as a manager I had gone from top of the tree to an absolute nightmare. I started with a crowd of 34 people – we used to announce the crowd changes to the team – but with Cheeseman’s arrival in the summer and putting up the money to buy players and us getting promotion, the average gate went up to 1,000. Now we were facing disaster. The taxman was after us, the VAT man was after us, everybody was after us …

All the players and I had to give statements to the police. Cheeseman said to me once: ‘Barry, this was a good thing gone wrong. We were just unlucky. I’ll get out of it, no problem. The finance manager did nothing wrong, he couldn’t get out of it. I blackmailed him. I had him by the bollocks.’

When he got arrested he changed his story. He said that he knew nothing about it. It was the finance manager’s idea and it was down to him. The police came to see me and told me that and I said I had to go with the finance manager because I was once in a room with Cheeseman and he admitted he had done it all. I told them that he wasn’t turning it round like that and I would go to court and say that.

I was in court and Keith came in. It was the first time I had seen him for six months and he threw his arms around me.

‘Hello Basil,’ he greeted me affectionately. ‘How are you doing?’

I told him I was there to give evidence against him.

‘You’ve got to do what you’ve got to do in this world, ain’t you boy!’

He was unbelievable. Never ever down, the geezer.

The police, when interviewing me, had said: ‘Well, you took these loans out and unless you confess you’re in big trouble.’ I said: ‘I can’t confess. I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

And I really didn’t, but because everybody thought Keith and I were so close, it appeared to them that I was in on the whole scam. Socially we saw each other now and then at big functions and that’s all. There was never a one-to-one. We were not close – I hardly ever saw him. He was always running down the stairs to jump in his car to go to the airport.