Полная версия:

Vixen

Epigraph

Love is the longing

for the half of ourselves

we have lost

from The Unbearable Lightness of Being

by Milan Kundera

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

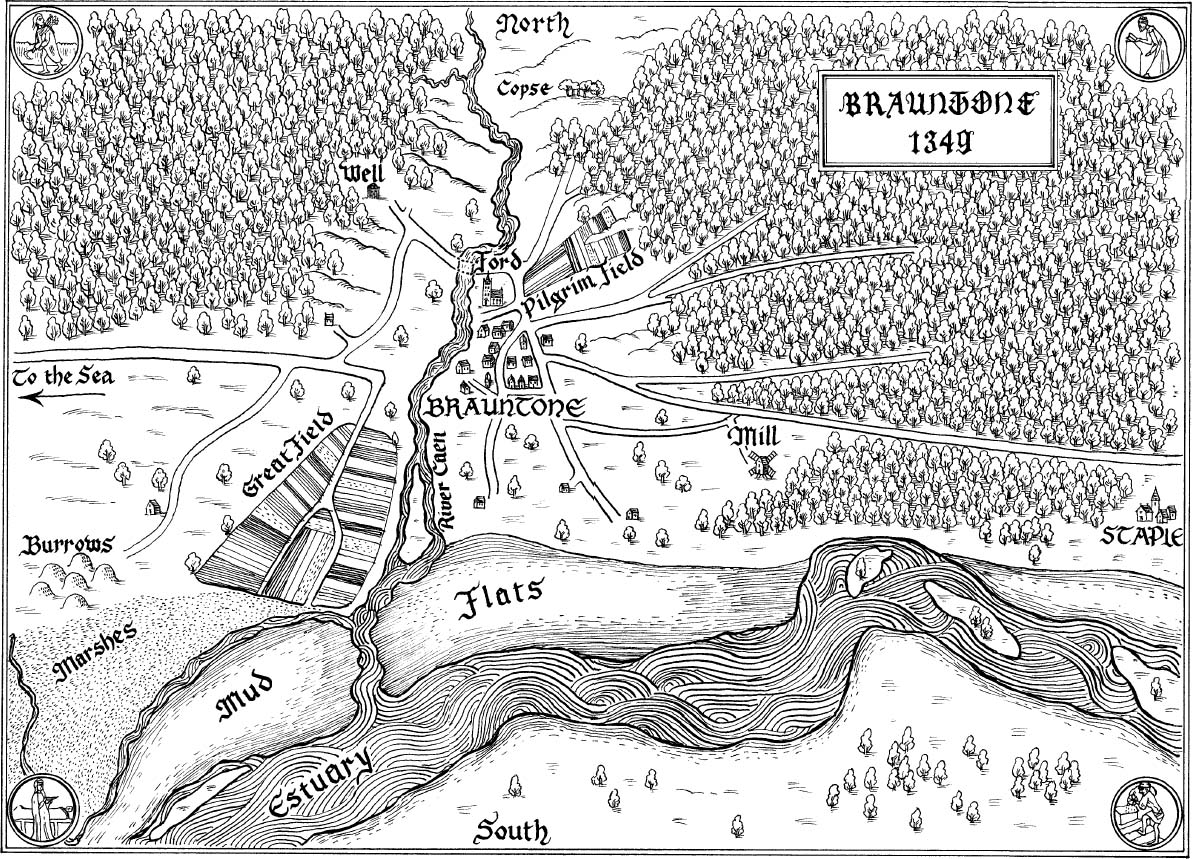

Map

Vigils: 1395

Anne

Advent: 1348

Vixen

Mattins: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Lauds: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Prime: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Terce: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Sext: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

None: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Vespers: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Compline: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Anne

Vixen

Nocturns: 1349

Thomas of Upcote

Vixen

Nunc Dimittis

Anne

About the Author

Also by Rosie Garland

Copyright

About the Publisher

VIGILS 1395

ANNE

I declare at the start that I was muddle-brained and spoilt. There. It is out.

For all that, I shall have my say. I wasted years holding my tongue, and the older I grow, the less I am inclined to wastage of any kind, be it time, or bread, or affection. I have not been a particularly good woman, by the reckoning of men. Nor have I been especially wicked. I have been close enough to Death to rub elbows, and what I saw in His eyes did not affright me.

Before I go into His great sleep, I should like to see the village once again: walk along Silver Street, turn west at the crossroads on to Church Street, lift my skirts and paddle through the ford where the Caen runs shallow, pass the church and arrive at the house. There shall I pause, hand on the gatepost, and look up the path to the door. Memory preserves things as they were, not as they are: I see the windows shuttered, more oilcloth than glass in the panes; the thatch half-rotten; the raw patch on the door where the Maid picked at the wood. Therein I saw out my fifteenth and came into my sixteenth year. Such a scant number of months, yet they encompassed a lifetime.

I think of the child I was. I think of Margret, my beloved friend. What she had in prettiness I possessed in plainness, although no mirror could persuade me of that fact. I was queen of my hearth, and carried that conviction into our games. I envied her and she bore the burden of my contrary nature with great meekness. I wish I had been a kinder companion. For does not Paul declare that the first shall be last and the last first?

I wish I could have seen where my feet were carrying me, the dangers of that path. If I had my time again – but here I go, twittering pointless wishes and dreams.

Perhaps my greatest foolishness was to think a grander fate awaited me: better than my sister Cat and her snot-nosed hatchling; better than my dam, planting turnips to feed us through hungry winters; at the very least, better than my brother Adam, gutted for some lord’s whim on a battlefield far from home.

Adam was an oak given breath: as tall, as strong, as gentle. When I wept he was my comfort. He strove to make me laugh, made me his special pet, bore me on his shoulders in games of horse and rider where I was his little lady fair and he my sturdy palfrey. He brought me pretty morsels: a roasted pigeon’s heart, marchpane from the Staple fair, a ribbon so blue I thought the sky should hang its head for being outdone in blueness.

He rose each morning, the sun of my life. The light he cast warmed the mud of my childish heart and I bloomed. I spent many an hour squeezing the muscles of his arm, transformed into rock by the rigours of drawing back the bowstring until the fletchings tickled his ear. How I cheered him at village contests, although he never carried off the prize. I could not understand, in my mind he was the best archer, the best brother, the best man at every task. He was my first love, my best love. I adored him with the innocent and all-consuming passion of a child, before she eats the apple and knows evil in the world.

Then, one spring, just after Candlemas, he was called to fight in France and we did not see him again. We lacked his body to grieve over, and mourned an emptiness that was without solace. I howled fit to tear the sky in half. I wanted God to tumble through the rift and fall to our patch of earth so that I could stick out my lip and demand, face to face, that He bring Adam back from dust. I was greedy with misery and believed none other felt it but me. No one slapped me out of my selfishness, not even Cat. I wept and wept until, just as suddenly, I stopped.

I woke that morning and watched my soul quit my body, slipping across the sea to join Adam. I became a girl without a shadow, a half-girl. I ate, I slept, I crouched over the bucket and squeezed myself empty, but was as lacking of life as the wooden saints in the church. My hands made gestures, my feet moved when commanded, but I was stiff, carved from some tough material that was no longer flesh.

When I placed myself in the path of the new priest, Father Thomas, I reasoned that it was out of desire and affection, rather than a hunger for possessions to fill the empty place in my soul. I thought to find consolation. Not raising up to an estate I had no right to, but some peace. I wanted a mild man who lifted his hand only to bless me; a modest house to call my home; a son who toddled on fat legs to bury his face in his mother’s lap. I did not start making sense of the world until much later.

I lost the better part of myself when Adam died and did not get any of it back until the Maid came to the village. My Maid, if I may make so bold – and I do, for I have grown courageous. Of all the folk who have burnished my life, she is the one I wish to see the most. She was flint to my iron. Dull as I was, she struck fire and I have burned bright since that first spark.

I think of her always; yet she comes rarely to my mind. It is a conundrum and I apologise. She was never fenced in, not with words and certainly not by any effort of man. I fear I will not capture her, either. But that part of my tale must wait a short while. There is more to tell, and there is time.

ADVENT 1348

VIXEN

Must I speak?

Must I stand here, say my piece? Make my words dance to the cramped tune of quill and ink? Must I squeeze myself onto the scored lines stretched tight across this page of parchment? I have no time for books – not that the likes of me can read them. Wear out my eyes squinting at scribbles when I could be lying on my back looking up at the clouds? I’d rather read their restless journey from lands where no man has set foot, and what they saw there.

I need no one, I want no one and no one wants me. That is the finest way to pass through this world, running so swiftly even the air cannot stick. I shake off everything as a fox sheds its tail when the hounds take hold. I’ll skip through this world tailless rather than not at all.

I scratch my scars: the ones on my back, the ones between my legs, the ones between my ears. They itch, particularly when the wind has a mind to change. This year is such a wild turnabout that the earth creaks with the upside-down, pitch-and-toss of it all. What’s at the end I know not, but a topsy-turvy world suits me. It opens new doors to slide through and leap out onto a different side.

Through it all I sing and dance and keep a step or two ahead of Death. Of course He is always there, but for the most part keeps His distance: playing His pipe on the roof-ridge of the next church but one, supping ale in the tavern I was in yesterday, banging on my neighbour’s door all night. The rat-tat-tat keeps me awake but I do not care, for it is not my door.

This year He draws too close for comfort.

I’m the first to see Him. I’m on the quayside, watching ships come in. He stands on the prow of the largest, waving. I’m the only one to wave back. Even from this distance I can hear Him piping out the mortal tune that is playing across the world, from Jerusalem to Rome and all the way to this slack lump of muck.

A woman at my elbow, head bundled up against the winter, says, ‘Who do you see? Who’s there?’

‘Don’t you see Him?’ I say.

‘Who?’

‘The pestilence!’ I cry.

‘Don’t say that!’ she hisses. ‘What are you trying to do; bring it down upon us?’ I laugh until she twists away, making the sign of horns with her fingers.

The moment the ships tie up, it begins.

I see three ships come sailing in with wine and glass, bolts of cloth and spices, things I may name but never dream of owning. Mooring ropes are thrown out: hands catch them, loop them tight, sew the hulks to the hem of the harbour. Rats skitter down the ropes and into town. The gangplank sticks out its tongue and the hold breathes out. I smell what’s on the air. These ships are spewing out the taste of Death.

I know the truth as I know the lines on my hand: this is the Great Mortality come at last. I see Him: strolling down the walkway, trailing rotten robes, worms tumbling in his wake. He steps on to the quayside, licking His lips, for He loves the savour of man and woman, old and young, rich and poor. I look Him in the eye and He grins.

‘Aren’t you afraid of me?’ He growls, and only I am shrewd enough to hear. ‘Aren’t you fearful of my bony fingers, ready to snatch and snuff you out? Of the smile that stretches to my ears? My wormy guts, the sores and scars and scabs I’m studded with? Doesn’t it make you want to piss yourself and run?’

Of course I’m terrified. Only a simpleton would not be. But I fix His hollow eye with mine and shrug. I’ve seen worse painted on church walls: seen bloodier, blacker, harsher.

‘Let others run, and scream, and fall,’ I say. ‘If it’s really you, I’d rather dance.’ I smile. ‘I’ve heard so much about you. About the fever you bring this year.’

Oh, how He picks up his heels and rattles them along the street! Elbows clattering in and out, knees up, knees down, fingers snapping, clapping His great jaws together, arms a frantic windmill.

‘All fall down!’ He sings.

There’s never been anything so fit to make you roar: we two capering fools, skipping along the harbour wall. I laugh until I ache. Of course, He falls in love with me and I have to dodge His kisses.

‘Marry me!’ He croons. ‘I’ll give you such a dowry as will snatch your breath away! Make you the richest bride in seven kingdoms!’ He promises. ‘I’ll furnish a feast that goes on seven days and seven nights! Silk for your sheets! Wine till you burst!’

But dancing is all I want. So I dance, and watch others die.

The harbour-dwellers are first to sicken. They say it’s foul air brought by the ships. The breath of a latrine may make me gag, but cannot kill me. I’ve cleaned up rich men’s shit for long enough to know.

I see men die, and beasts live. Especially the horses: Death hates their odour, which makes me love it, purely to annoy Him. Then there are the rats, too small for men to notice. What is a rat? Of no more consequence than a girl. A girl who does not know her letters, but can read men. Who does not know her prayers, but knows what they are for. Who is tired of waiting for a saviour to turn stones into loaves.

I hear tales about punishment for sins, the wrath of the Lord. As for God’s anger, I’ll say nothing: not for fear of Heaven striking me down, but for the anger of men, who fear the fragility of their faith so keenly they would burn a child who spoke one small word against it.

I dance down the coast, from village to village. The first time, I tell the truth and say I am come from Bristol. They smell trouble and I escape with my skin, racing from hurled rocks and cudgels, only stopping when I am in the forest and they will not follow. I spit on the path that leads back.

The next place I am wiser, but still am chased off. I run: not only from their fists but also from the fever I smell on their breath, the roses blooming in their throats. I avoid villages, sniff out the stink of men and keep away. I use their fields for my larder; learn to move quickly. And all the while I keep one step ahead of the fearsome dancing partner whose breath rots the road behind.

We make a good pair, Death and I. As long as I can pique His interest, amuse Him with a merry expression and fancy riddles, He does not bid me stop. As long as I am more valuable alive than dead, He does not draw me into His most intimate and final of embraces. Each morning I devise a fresh amusement and play it out, ear cocked for His approving chuckle. Poised for dangerous silence.

I point to a man and say, This one?

He nods, and I start my game: steal a string of sausages from under the butcher’s nose, piss on the blacksmith’s fire, throw sand between the miller’s stones, spit on my lady’s poached halibut. I watch them fume and shake their fists, so consumed with anger they do not see the towering darkness behind them till He taps on their shoulder and there’s no time for hand-wringing and pleas for mercy.

I boast, hoping he cannot hear my desperation.

See how light I can make your labour?

Did you ever have such fun before?

What diversions. What amusements! Do I not garland your workaday world with wonders?

It’s a thin path to tread: I must not get so close that He gathers me into His arms and presses His stinking lips to mine. I must not strike a bargain, their lives for mine; nothing so dangerous as spare me and I will make you laugh. I am not so stupid as to spit on my palm and shake Death’s hand. I’ll keep myself well clear of His claw.

I am a jolly-man, a wooden-head; not everyman, but every-fool. I dance, I sing, turn cartwheels and weave my body into knots. For Him I flit between boy and girl, between dog and vixen; so fast that I lose sight of what I am, submerged in the swirling, glittering soup of my creations.

I am exhausted. So very tired of all this labour, this hanging on to life.

MATTINS 1349

The Feast of Saint Brannoc

THOMAS OF UPCOTE

Because I could not hear the voice of God, I went to the fields.

I woke early, hoping to find a small corner of quiet in my church, but there was none. Before dawn I knelt at the altar, straining to hear the Lord but instead heard some farmer bawling for his cow. By first light this solitary cry had swelled into a wild congregation of yawning and farting and belching and pissing and wailing and sneezing and hawking and cracking of stretched limbs and banging of doors and no chance to hear the boldest cock crow over the dreadful racket.

So I went into the meadow. The morning was brisk: crisp bracken, brown as crumbled horse-bread, curled into itself as though trying to keep warm. Holly thickened the hedgerow, beside thorn bushes and grey-skinned ash with its black fists of buds. Small birds fluttered alongside, keeping pace with my steps.

I strode to the centre of the field. The earth spread its cloak beneath my feet, prickly with barley stalks cut close as stubble on a man’s chin. The breath of the dawn rose in a mist. Drops of water hung at the tips of the grass stems, catching the new light. Rooks splashed in the rutted puddles that lay athwart the fields. Over the sea to the west the sky was dark; the brightness of coming day showed itself to the east.

I shook my head of these distractions, pressed on, dropped to my knees. The dew came straightway through my hose and chilled me awake. I listened: nothing but my own happy breath. I pressed my palms together and spoke the beautiful words of the Office under the roof of God’s sky. No one bothered me with, Father Thomas, are you sick? I did not have to snap, No; I am at prayer. I am your priest. I pray. It is what we do. It was delightful.

For a moment only. A crow cawed, emptying its throat of sand. Its fellow answered from three fields away, echoed by the clattering of magpies. A cow mourned for her calf, taken at the last harvest. Bullocks steamed, sheep coughed at the sparse winter grass. All I asked was a little peace. If Hell was unimaginable pain and Heaven was unimaginable bliss, then the bliss I sought was humble silence. I shook my head, tried to retrieve the silence I tasted when I first knelt.

But here was a fox crying with the voice of a whipped boy, the dit-dit-swee of the titmouse, the rattling chatter of robins, the twee-twee of dunnocks, the bubbling of blackbirds. Seagulls cackled at some private joke. I pushed away the thought that it was myself they found so amusing.

I prostrated myself upon the earth and inhaled the reek of its dark breath, rolled over and lay on my back, stared upwards into the bowl of the heavens: the half-darkness unrippled by clouds, the stars closing their bright eyes one by one as the approaching daylight spread itself across the sky.

Can you not pray, my son? Am I so difficult a master?

I groaned. My disobedient senses were drawing me away from God. I shut my eyes tight, shoved my fingers into my ears till all I could hear was the hissing of the fire in my head.

‘Oh God!’ I bellowed, to drown out the world around me.

My heart slowed. Oh Lord, behold Your servant. That was the sum and total of my prayer, for the hour of the Office was done. It was time for me to spit upon my hands and labour for God. The pilgrims would come today and I would be ready.

I hitched my cassock and splashed through the ford into the village, slapping warmth into the cold meat of my thighs. Rain slanted down onto the thatch, gathering itself together for another busy day. There had been no frost all winter, only this steady river falling from the sky and making the fields swim. But the rain must stop soon: it was almost spring.

William stood at the lychgate collecting donations from the gathered pilgrims. He was a fine steward, and I could not fault him for the wholehearted way he displayed his stave of office with its clubbed head of brass. He stopped short of affrighting people, as a rule. Lukas stood at his side, arms folded, eyeing the crowd keenly for anyone who might try to slip in without payment. He grinned, tying up a sack of candles ready to be hauled away to the treasury.

‘It is a good take today, Father,’ he said, squeezing rain from his beard. ‘There’s two bags of tapers put by already and we’re barely past breakfast.’

‘The people turn to the Lord in earnest,’ I replied soberly. ‘That is what matters.’

‘Numbers are up,’ said William, gloating.

I would speak with him, another time. ‘The Saint’s intercession is most powerful,’ I said. ‘He has never failed us.’

‘Indeed, Father,’ he said. ‘Very good to us, he is. And don’t these folk know it,’ he roared, sweeping his arm in a gesture encompassing the company. ‘Come for a piece of his goodness, every one of them.’

‘It’s a fine thing he’s so generous,’ added Lukas.

Aline bawled a greeting and pushed a wooden mug into my hands.

‘There you go, Father! The Saint’s ale itself. Fresh this morning and I never brewed a better, if I say so myself.’

Her face was red. I decided to take it for hard work rather than hard drinking. I sniffed the pot, not discourteously, and took a mouthful.

‘It is good, mistress.’

She grinned. ‘Bless you, Father!’ She turned round, took a deep breath and bellowed, ‘He likes it! Good enough for the Saint’s man, more than good enough for us, so it is!’

There was an answering cheer from the multitude, many a cup raised. I picked my way through the field of folk, spread thick as daisies upon the grass. They regaled me with tales of how the Saint saved them from drowning, healed broken arms and broken hearts, planted healthy sons in barren wombs, cured this sickness and that sickness till my head spun and my arm wearied from pumping up and down in blessing.

A man laid on the ground stretched out his arm and grasped my ankle. Though his shoulders were broad and muscular, his legs were so thin they could not bear his weight. The bones of his knees were as big as cabbages.

‘Father,’ he croaked. ‘Can your Saint save us from the pestilence?’

With the speed of a bucket of water hurled onto a fire, the pilgrims fell silent. The burden of their glances heaped on my shoulders.

‘My son,’ I said, making the sign of the Cross upon his brow. ‘Pray to the most holy Brannoc. God have mercy upon you.’

The man shook his head petulantly. ‘The pestilence, Father. Are his relics proof against the Great Dying?’

The crowd hissed through their teeth at the dangerous words. Inch by inch they drew back, clearing a circle of mud around him. One old female muttered under her breath and made the sign of horns with her fingers. I glared at her for indulging in such heathen tomfoolery. She ignored me and spat at my feet. I closed my eyes and called upon the Lord to plant the right words into my mouth.

‘Only God knows the workings of His will.’ There was a groan, and not a little sucking of teeth. ‘The pestilence is His will. It is punishment for our sins,’ I continued, gathering strength.

‘God forgive me!’ sobbed a man from somewhere in the mob.

He was hushed swiftly, and for once all ears turned to me with full attention.

‘But,’ I cried. ‘But,’ I repeated, for it was a good word and had captured them. ‘The Saint is a strong protector. Not one goodman or goodwife of this village has perished since the Great Mortality came to this land.’

My words stirred up a hubbub of excitement: they hung on to my coat, pawing at my arms, heaping thanks upon my head and calling down the blessings of the Saint for some miracle they thought had taken place. I wriggled free of their clinging and hurried to the church, its hulk looming out of the drizzle like a monstrous bull. I patted its flank and let myself in by the small north door; laid my back to the wood, closed my eyes, stretched out my hand and brushed the plaster of the wall, warm and soft as a child’s cheek. Oh Lord, behold Your servant.