Полная версия:

The Complete Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars

THE COMPLETE MARS TRILOGY

Red Mars

Green Mars

Blue Mars

Kim Stanley Robinson

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Red Mars

Previously published in paperback by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993

Published in paperback by HarperVoyager 1996

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1992

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2009

Copyright © Kim Stanley Robinson 1992

Green Mars

Previously published in paperback by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1994

Published in paperback by HarperVoyager 1996

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1992

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2009

Copyright © Kim Stanley Robinson 1994

Blue Mars

Previously published in paperback by Voyager 1996

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 1996

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2009

Copyright © Kim Stanley Robinson 1996

Cover Photographs © Kees Veenenbos/Science Photo Library

Kim Stanley Robinson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBNs: 9780007401703, 9780007402090, 9780007402175

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780008121778

Version: 2017-11-20

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Red Mars

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: Festival Night

Part Two: The Voyage Out

Part Three: The Crucible

Part Four: Homesick

Part Five: Falling Into History

Part Six: Guns Under the Table

Part Seven: Senzeni Na

Part Eight: Shikata Ga Nai

Green Mars

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: Areoformation

Part Two: The Ambassador

Part Three: Long Runout

Part Four: The Scientist As Hero

Part Five: Homeless

Part Six: Tariqat

Part Seven: What Is To Be Done?

Part Eight: Social Engineering

Part Nine: The Spur of the Moment

Part Ten: Phase Change

Blue Mars

Title Page

Dedication

Part One: Peacock Mountain

Part Two: Areophany

Part Three: A New Constitution

Part Four: Green Earth

Part Five: Home at Last

Part Six: Ann in the Outback

Part Seven: Making Things Work

Part Eight: The Green and the White

Part Nine: Natural History

Part Ten: Werteswandel

Part Eleven: Viriditas

Part Twelve: It Goes So Fast

Part Thirteen: Experimental Procedures

Part Fourteen: Phoenix Lake

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also By Kim Stanley Robinson

About the Publisher

RED MARS

Kim Stanley Robinson

Dedication

For Lisa

PART ONE Festival Night

Mars was empty before we came. That’s not to say that nothing had ever happened. The planet had accreted, melted, roiled and cooled, leaving a surface scarred by enormous geological features: craters, canyons, volcanoes. But all of that happened in mineral unconsciousness, and unobserved. There were no witnesses – except for us, looking from the planet next door, and that only in the last moment of its long history. We are all the consciousness that Mars has ever had.

Now everybody knows the history of Mars in the human mind: how for all the generations of prehistory it was one of the chief lights in the sky, because of its redness and fluctuating intensity, and the way it stalled in its wandering course through the stars, and sometimes even reversed direction. It seemed to be saying something with all that. So perhaps it is not surprising that all the oldest names for Mars have a peculiar weight on the tongue – Nirgal, Mangala, Auqàkuh, Harmakhis – they sound as if they were even older than the ancient languages we find them in, as if they were fossil words from the Ice Age or before. Yes, for thousands of years Mars was a sacred power in human affairs; and its color made it a dangerous power, representing blood, anger, war and the heart.

Then the first telescopes gave us a closer look, and we saw the little orange disk, with its white poles and dark patches spreading and shrinking as the long seasons passed. No improvement in the technology of the telescope ever gave us much more than that; but the best Earthbound images gave Lowell enough blurs to inspire a story, the story we all know, of a dying world and a heroic people, desperately building canals to hold off the final deadly encroachment of the desert.

It was a great story. But then Mariner and Viking sent back their photos, and everything changed. Our knowledge of Mars expanded by magnitudes, we literally knew millions of times more about this planet than we had before. And there before us flew a new world, a world unsuspected.

It seemed, however, to be a world without life. People searched for signs of past or present Martian life, anything from microbes to the doomed canal-builders, or even alien visitors. As you know, no evidence for any of these has ever been found. And so stories have naturally blossomed to fill the gap, just as in Lowell’s time, or in Homer’s, or in the caves or on the savannah – stories of microfossils wrecked by our bio-organisms, of ruins found in dust storms and then lost forever, of Big Man and all his adventures, of the elusive little red people, always glimpsed out of the corner of the eye. And all of these tales are told in an attempt to give Mars life, or to bring it to life. Because we are still those animals who survived the Ice Age, and looked up at the night sky in wonder, and told stories. And Mars has never ceased to be what it was to us from our very beginning – a great sign, a great symbol, a great power.

And so we came here. It had been a power; now it became a place.

“…And so we came here. But what they didn’t realize was that by the time we got to Mars, we would be so changed by the voyage out that nothing we had been told to do mattered anymore. It wasn’t like submarining or settling the Wild West – it was an entirely new experience, and as the flight of the Ares went on, the Earth finally became so distant that it was nothing but a blue star among all the others, its voices so delayed that they seemed to come from a previous century. We were on our own; and so we became fundamentally different beings.”

All lies, Frank Chalmers thought irritably. He was sitting in a row of dignitaries, watching his old friend John Boone give the usual Boone Inspirational Address. It made Chalmers weary. The truth was, the trip to Mars had been the functional equivalent of a long train ride. Not only had they not become fundamentally different beings, they had actually become more like themselves than ever, stripped of habits until they were left with nothing but the naked raw material of their selves. But John stood up there waving a forefinger at the crowd, saying “We came here to make something new, and when we arrived our earthly differences fell away, irrelevant in this new world!” Yes, he meant it all literally. His vision of Mars was a lens that distorted everything he saw, a kind of religion.

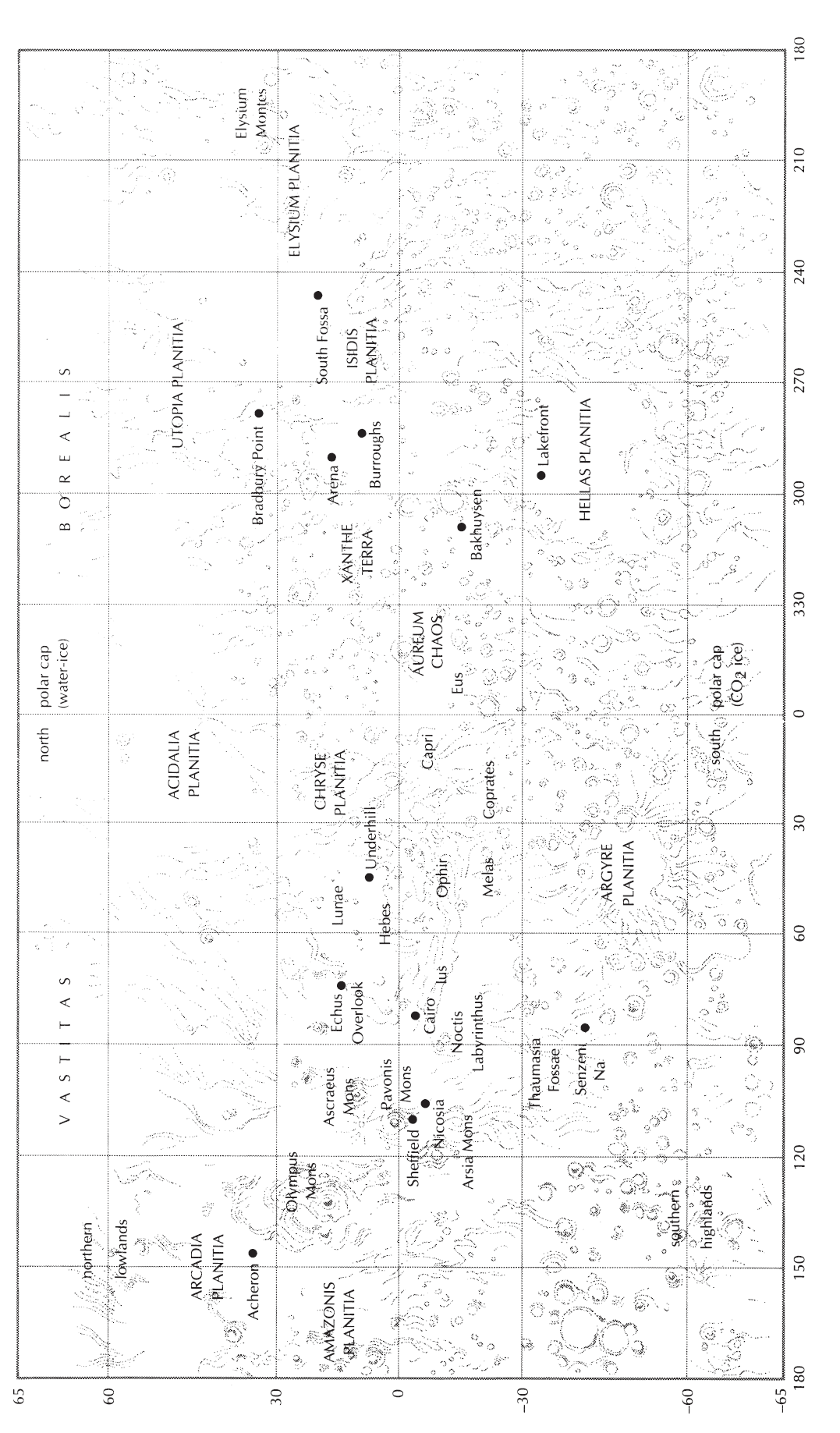

Chalmers stopped listening and let his gaze wander over the new city. They were going to call it Nicosia. It was the first town of any size to be built free-standing on the Martian surface; all the buildings were set inside what was in effect an immense clear tent, supported by a nearly invisible frame, and placed on the rise of Tharsis, west of Noctis Labyrinthus. This location gave it a tremendous view, with a distant western horizon punctuated by the broad peak of Pavonis Mons. For the Mars veterans in the crowd it was giddy stuff: they were on the surface, they were out of the trenches and mesas and craters, they could see forever! Hurrah!

A laugh from the audience drew Frank’s attention back to his old friend. John Boone had a slightly hoarse voice and a friendly Midwestern accent, and he was by turns (and somehow even all at once) relaxed, intense, sincere, self-mocking, modest, confident, serious, and funny. In short, the perfect public speaker. And the audience was rapt; this was the First Man On Mars speaking to them, and judging by the looks on their faces they might as well have been watching Jesus produce their evening meal out of the loaves and fishes. And in fact John almost deserved their adoration, for performing a similar miracle on another plane, transforming their tin can existence into an astounding spiritual voyage. “On Mars we will come to care for each other more than ever before,” John said, which really meant, Chalmers thought, an alarming incidence of the kind of behavior seen in rat overpopulation experiments; “Mars is a sublime, exotic and dangerous place,” said John – meaning a frozen ball of oxidized rock on which they were exposed to about fifteen rem a year; “And with our work,” John continued, “we are carving out a new social order and the next step in the human story” – i.e. the latest variant in primate dominance dynamics.

John finished with this flourish, and there was, of course, a huge roar of applause. Maya Toitovna then went to the podium to introduce Chalmers. Frank gave her a private look which meant he was in no mood for any of her jokes; she saw it and said, “Our next speaker has been the fuel in our little rocket ship,” which somehow got a laugh. “His vision and energy are what got us to Mars in the first place, so save any complaints you may have for our next speaker, my old friend Frank Chalmers.”

At the podium he found himself surprised by how big the town appeared. It covered a long triangle, and they were gathered at its highest point, a park occupying the western apex. Seven paths rayed down through the park to become wide, tree-lined, grassy boulevards. Between the boulevards stood low trapezoidal buildings, each faced with polished stone of a different color. The size and architecture of the buildings gave things a faintly Parisian look, Paris as seen by a drunk Fauvist in spring, sidewalk cafes and all. Four or five kilometers downslope the end of the city was marked by three slender skyscrapers, beyond which lay the low greenery of the farm. The skyscrapers were part of the tent framework, which overhead was an arched network of sky-colored lines. The tent fabric itself was invisible, and so taken all in all, it appeared that they stood in the open air. That was gold. Nicosia was going to be a popular city.

Chalmers said as much to the audience, and enthusiastically they agreed. Apparently he had the crowd, fickle souls that they were, about as securely as John. Chalmers was bulky and dark, and he knew he presented quite a contrast to John’s blond good looks; but he knew as well that he had his own rough charisma, and as he warmed up he drew on it, falling into a selection of his own stock phrases.

Then a shaft of sunlight lanced down between the clouds, striking the upturned faces of the crowd, and he felt an odd tightening in his stomach. So many people there, so many strangers! People in the mass were a frightening thing – all those wet ceramic eyes encased in pink blobs, looking at him … it was nearly too much. Five thousand people in a single Martian town. After all the years in Underhill it was hard to grasp.

Foolishly he tried to tell the audience something of this. “Looking,” he said. “Looking around – the strangeness of our presence here is – accentuated.”

He was losing the crowd. How to say it? How to say that they alone in all that rocky world were alive, their faces glowing like paper lanterns in the light? How to say that even if living creatures were no more than carriers for ruthless genes, this was still, somehow, better than the blank mineral nothingness of everything else?

Of course he could never say it. Not at any time, perhaps, and certainly not in a speech. So he collected himself. “In the Martian desolation,” he said, “the human presence is, well, a remarkable thing” (they would care for each other more than ever before, a voice in his mind repeated sardonically). “The planet, taken in itself, is a dead frozen nightmare” (therefore exotic and sublime), “and so thrown on our own, we of necessity are in the process of – reorganizing a bit” (or forming a new social order) – so that yes, yes, yes, he found himself proclaiming exactly the same lies they had just heard from John!

Thus at the end of his speech he too got a big roar of applause. Irritated, he announced it was time to eat, depriving Maya of her chance for a final remark. Although probably she had known he would do that and so hadn’t bothered to think of any. Frank Chalmers liked to have the last word.

People crowded onto the temporary platform to mingle with the celebrities. It was rare to get this many of the first hundred in one spot anymore, and people crowded around John and Maya, Samantha Hoyle, Sax Russell and Chalmers.

Frank looked over the crowd at John and Maya. He didn’t recognize the group of Terrans surrounding them, which made him curious. He made his way across the platform, and as he approached he saw Maya and John give each other a look. “There’s no reason this place shouldn’t function under normal law,” one of the Terrans was saying.

Maya said to him, “Did Olympus Mons really remind you of Mauna Loa?”

“Sure,” the man said. “Shield volcanoes all look alike.”

Frank stared over this idiot’s head at Maya. She didn’t acknowledge the look. John was pretending not to have noticed Frank’s arrival. Samantha Hoyle was speaking to another man in an undertone, explaining something; he nodded, then glanced involuntarily at Frank. Samantha kept her back turned to him. But it was John who mattered, John and Maya. And both were pretending that nothing was out of the ordinary; but the topic of conversation, whatever it had been, had gone away.

Chalmers left the platform. People were still trooping down through the park, toward tables that had been set in the upper ends of the seven boulevards. Chalmers followed them, walking under young transplanted sycamores; their khaki leaves colored the afternoon light, making the park look like the bottom of an aquarium.

At the banquet tables construction workers were knocking back vodka, getting rowdy, obscurely aware that with the construction finished, the heroic age of Nicosia was ended. Perhaps that was true for all of Mars.

The air filled with overlapping conversations. Frank sank beneath the turbulence, wandered out to the northern perimeter. He stopped at a waist-high concrete coping: the city wall. Out of the metal stripping on its top rose four layers of clear plastic. A Swiss man was explaining things to a group of visitors, pointing happily.

“An outer membrane of piezoelectric plastic generates electricity from wind. Then two sheets hold a layer of airgel insulation. Then the inner layer is a radiation-capturing membrane, which turns purple and must be replaced. More clear than a window, isn’t it?”

The visitors agreed. Frank reached out and pushed at the inner membrane. It stretched until his fingers were buried to the knuckles. Slightly cool. There was faint white lettering printed on the plastic: Isidis Planitia Polymers. Through the sycamores over his shoulder he could still see the platform at the apex. John and Maya and their cluster of Terran admirers were still there, talking animatedly. Conducting the business of the planet. Deciding the fate of Mars.

He stopped breathing. He felt the pressure of his molars squeezing together. He poked the tent wall so hard that he pushed out the outermost membrane, which meant that some of his anger would be captured and stored as electricity in the town’s grid. It was a special polymer in that respect; carbon atoms were linked to hydrogen and fluorine atoms in such a way that the resulting substance was even more piezoelectric than quartz. Change one element of the three, however, and everything shifted; substitute chlorine for fluorine, for instance, and you had saran wrap.

Frank stared at his wrapped hand, then up again at the other two elements, still bonded to each other. But without him they were nothing!

Angrily he walked into the narrow streets of the city.

Clustered in a plaza like mussels on a rock were a group of Arabs, drinking coffee. Arabs had arrived on Mars only ten years before, but already they were a force to be reckoned with. They had a lot of money, and they had teamed up with the Swiss to build a number of towns, including this one. And they liked it on Mars. “It’s like a cold day in the Empty Quarter,” as the Saudis said. The similarity was such that Arabic words were slipping quickly into English, because Arabic had a larger vocabulary for this landscape: akaba for the steep final slopes around volcanoes, badia for the great world dunes, nefuds for deep sand, seyl for the billion year-old dry river beds … people were saying they might as well switch over to Arabic and have done with it.

Frank had spent a fair bit of time with Arabs, and the men in the plaza were pleased to see him. “Salaam aleykl” they said to him, and he replied, “Marhabba!” White teeth flashed under black moustaches. Only men present, as usual. Some youths led him to a central table where the older men sat, including his friend Zeyk. Zeyk said, “We are going to call this square Hajr el-kra Meshab, ‘the red granite open place in town.’” He gestured at the rust-colored flagstones. Frank nodded and asked what kind of stone it was. He spoke Arabic for as long as he could, pushing the edges of his ability and getting some good laughs in response. Then he sat at the central table and relaxed, feeling like he could have been on a street in Damascus or Cairo, comfortable in the wash of Arabic and expensive cologne.

He studied the men’s faces as they talked. An alien culture, no doubt about it. They weren’t going to change just because they were on Mars, they put the lie to John’s vision. Their thinking clashed radically with Western thought; for instance the separation of church and state was wrong to them, making it impossible for them to agree with Westerners on the very basis of government. And they were so patriarchal that some of their women were said to be illiterate – illiterates, on Mars! That was a sign. And indeed these men had the dangerous look that Frank associated with machismo, the look of men who oppressed their women so cruelly that naturally the women struck back where they could, terrorizing sons who then terrorized wives who terrorized sons and so on and so on, in an endless death spiral of twisted love and sex hatred. So that in that sense they were all madmen.

Which was one reason Frank liked them. And certainly they would come in useful to him, acting as a new locus of power. Defend a weak new neighbor to weaken the old powerful ones, as Machiavelli had said. So he drank coffee, and gradually, politely, they shifted to English.

“How did you like the speeches?” he asked, looking into the black mud at the bottom of his demitasse.

“John Boone is the same as ever,” old Zeyk replied. The others laughed angrily. “When he says we will make an indigenous Martian culture, he only means some of the Terran cultures here will be promoted, and others attacked. Those perceived as regressive will be singled out for destruction. It is a form of Ataturkism.”

“He thinks everyone on Mars should become American,” said a man named Nejm.

“Why not?” Zeyk said, smiling. “It’s already happened on Earth.”

“No,” Frank said. “You shouldn’t misunderstand Boone. People say he’s self-absorbed, but—”

“He is self-absorbed!” Nejm cried. “He lives in a hall of mirrors! He thinks that we have come to Mars to establish a good old American superculture, and that everyone will agree to it because it is the John Boone plan.”

Zeyk said, “He doesn’t understand that other people have other opinions.”

“It’s not that,” Frank said. “It’s just that he knows they don’t make as much sense as his.”

They laughed at that, but the younger men’s hoots had a bitter edge. They all believed that before their arrival Boone had argued in secret against UN approval for Arab settlements. Frank encouraged this belief, which was almost true – John disliked any ideology that might get in his way. He wanted the slate as blank as possible in everybody who came up.

The Arabs, however, believed that John disliked them in particular. Young Selim el-Hayil opened his mouth to speak, and Frank gave him a swift warning glance. Selim froze, then pursed his mouth angrily. Frank said, “Well, he’s not as bad as all that. Although to tell the truth I’ve heard him say it would have been better if the Americans and Russians had been able to claim the planet when they arrived, like explorers in the old days.”

Their laughter was brief and grim. Selim’s shoulders hunched as if struck. Frank shrugged and smiled, spread his hands wide. “But it’s pointless! I mean, what can he do?”