Полная версия:

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

The Rational Optimist

How Prosperity Evolves

Matt Ridley

For Matthew and Iris

This division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual, consequence of a certain propensity in human nature which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.

ADAM SMITH

The Wealth of Nations

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

PROLOGUE When ideas have sex

CHAPTER 1 A better today: the unprecedented present

CHAPTER 2 The collective brain: exchange and specialisation after 200,000 years ago

CHAPTER 3 The manufacture of virtue: barter, trust and rules after 50,000 years ago

CHAPTER 4 The feeding of the nine billion: farming after 10,000 years ago

CHAPTER 5 The triumph of cities: trade after 5,000 years ago

CHAPTER 6 Escaping Malthus’s trap: population after 1200

CHAPTER 7 The release of slaves: energy after 1700

CHAPTER 8 The invention of invention: increasing returns after 1800

CHAPTER 9 Turning points: pessimism after 1900

CHAPTER 10 The two great pessimisms of today: Africa and climate after 2010

CHAPTER 11 The catallaxy: rational optimism about 2100

NOTES AND REFERENCES

INDEX

Acknowledgements

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE When ideas have sex

In other classes of animals, the individual advances from infancy to age or maturity; and he attains, in the compass of a single life, to all the perfection his nature can reach: but, in the human kind, the species has a progress as well as the individual; they build in every subsequent age on foundations formerly laid.

ADAM FERGUSON

An Essay on the History of Civil Society

On my desk as I write sit two artefacts of roughly the same size and shape: one is a cordless computer mouse; the other a hand axe from the Middle Stone Age, half a million years old. Both are designed to fit the human hand – to obey the constraints of being used by human beings. But they are vastly different. One is a complex confection of many substances with intricate internal design reflecting multiple strands of knowledge. The other is a single substance reflecting the skill of a single individual. The difference between them shows that the human experience of today is vastly different from the human experience of half a million years ago.

This book is about the rapid, continuous and incessant change that human society experiences in a way that no other animal does. To a biologist this is something that needs explaining. In the past two decades I have written four books about how similar human beings are to other animals. This book is about how different they are from other animals. What is it about human beings that enables them to keep changing their lives in this tumultuous way?

It is not as if human nature changes. Just as the hand that held the hand axe was the same shape as the hand that holds the mouse, so people always have and always will seek food, desire sex, care for offspring, compete for status and avoid pain just like any other animal. Many of the idiosyncrasies of the human species are unchanging, too. You can travel to the farthest corner of the earth and still expect to encounter singing, smiling, speech, sexual jealousy and a sense of humour – none of which you would find to be the same in a chimpanzee. You could travel back in time and empathise easily with the motives of Shakespeare, Homer, Confucius and the Buddha. If I could meet the man who painted exquisite images of rhinos on the wall of the Chauvet Cave in southern France 32,000 years ago, I have no doubt that I would find him fully human in every psychological way. There is a great deal of human life that does not change.

Yet to say that life is the same as it was 32,000 years ago would be absurd. In that time my species has multiplied by 100,000 per cent, from perhaps three million to nearly seven billion people. It has given itself comforts and luxuries to a level that no other species can even imagine. It has colonised every habitable corner of the planet and explored almost every uninhabitable one. It has altered the appearance, the genetics and the chemistry of the world and pinched perhaps 23 per cent of the productivity of all land plants for its own purposes. It has surrounded itself with peculiar, non-random arrangements of atoms called technologies, which it invents, reinvents and discards almost coninuously. This is not true for other creatures, not even brainy ones like chimpanzees, bottlenose dolphins, parrots and octopi. They may occasionally use tools, they may occasionally shift their ecological niche, but they do not ‘raise their standard of living’, or experience ‘economic growth’. They do not encounter ‘poverty’ either. They do not progress from one mode of living to another – nor do they deplore doing so. They do not experience agricultural, urban, commercial, industrial and information revolutions, let alone Renaissances, Reformations, Depressions, Demographic Transitions, civil wars, cold wars, culture wars and credit crunches. As I sit here at my desk, I am surrounded by things – telephones, books, computers, photographs, paper clips, coffee mugs – that no monkey has ever come close to making. I am spilling digital information on to a screen in a way that no dolphin has ever managed. I am aware of abstract concepts – the date, the weather forecast, the second law of thermodynamics – that no parrot could begin to grasp. I am definitely different. What is it that makes me so different?

It cannot just be that I have a bigger brain than other animals. After all, late Neanderthals had on average bigger brains than I do, yet did not experience this headlong cultural change. Moreover, big though my brain may be compared with another animal species, I have barely the foggiest inkling how to make coffee cups and paper clips, let alone weather forecasts. The psychologist Daniel Gilbert likes to joke that every member of his profession lives under the obligation at some time in his career to complete a sentence which begins: ‘The human being is the only animal that…’ Language, cognitive reasoning, fire, cooking, tool making, self-awareness, deception, imitation, art, religion, opposable thumbs, throwing weapons, upright stance, grandparental care – the list of features suggested as unique to human beings is long indeed. But then the list of features unique to aardvarks or bare-faced go-away birds is also fairly long. All of these features are indeed uniquely human and are indeed very helpful in enabling modern life. But I will contend that, with the possible exception of language, none of them arrived at the right time, or had the right impact in human history to explain the sudden change from a merely successful ape-man to an ever-expanding progressive moderniser. Most of them came much too early in the story and had no such ecological effect. Having sufficient consciousness to want to paint your body or to reason the answer to a problem is nice, but it does not lead to ecological world conquest.

Clearly, big brains and language may be necessary for human beings to cope with a life of technological modernity. Clearly, human beings are very good at social learning, indeed compared with even chimpanzees humans are almost obsessively interested in faithful imitation. But big brains and imitation and language are not themselves the explanation of prosperity and progress and poverty. They do not themselves deliver a changing standard of living. Neanderthals had all of these: huge brains, probably complex languages, lots of technology. But they never burst out of their niche. It is my contention that in looking inside our heads, we would be looking in the wrong place to explain this extraordinary capacity for change in the species. It was not something that happened within a brain. It was something that happened between brains. It was a collective phenomenon.

Look again at the hand axe and the mouse. They are both ‘man-made’, but one was made by a single person, the other by hundreds of people, maybe even millions. That is what I mean by collective intelligence. No single person knows how to make a computer mouse. The person who assembled it in the factory did not know how to drill the oil well from which the plastic came, or vice versa. At some point, human intelligence became collective and cumulative in a way that happened to no other animal.

Mating minds

To argue that human nature has not changed, but human culture has, does not mean rejecting evolution – quite the reverse. Humanity is experiencing an extraordinary burst of evolutionary change, driven by good old-fashioned Darwinian natural selection. But it is selection among ideas, not among genes. The habitat in which these ideas reside consists of human brains. This notion has been trying to surface in the social sciences for a long time. The French sociologist Gabriel Tarde wrote in 1888: ‘We may call it social evolution when an invention quietly spreads through imitation.’ The Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek wrote in the 1960s that in social evolution the decisive factor is ‘selection by imitation of successful institutions and habits’. The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in 1976 coined the term ‘meme’ for a unit of cultural imitation. The economist Richard Nelson in the 1980s proposed that whole economies evolve by natural selection.

This is what I mean when I talk of cultural evolution: at some point before 100,000 years ago culture itself began to evolve in a way that it never did in any other species – that is, to replicate, mutate, compete, select and accumulate – somewhat as genes had been doing for billions of years. Just like natural selection cumulatively building an eye bit by bit, so cultural evolution in human beings could cumulatively build a culture or a camera. Chimpanzees may teach each other how to spear bushbabies with sharpened sticks, and killer whales may teach each other how to snatch sea lions off beaches, but only human beings have the cumulative culture that goes into the design of a loaf of bread or a concerto.

Yes, but why? Why us and not killer whales? To say that people have cultural evolution is neither very original nor very helpful. Imitation and learning are not themselves enough, however richly and ingeniously they are practised, to explain why human beings began changing in this unique way. Something else is necessary; something that human beings have and killer whales do not. The answer, I believe, is that at some point in human history, ideas began to meet and mate, to have sex with each other.

Let me explain. Sex is what makes biological evolution cumulative, because it brings together the genes of different individuals. A mutation that occurs in one creature can therefore join forces with a mutation that occurs in another. The analogy is most explicit in bacteria, which trade genes without replicating at the same time – hence their ability to acquire immunity to antibiotics from other species. If microbes had not begun swapping genes a few billion years ago, and animals had not continued doing so through sex, all the genes that make eyes could never have got together in one animal; nor the genes to make legs or nerves or brains. Each mutation would have remained isolated in its own lineage, unable to discover the joys of synergy. Think, in cartoon terms, of one fish evolving a nascent lung, another nascent limbs and neither getting out on land. Evolution can happen without sex; but it is far, far slower.

And so it is with culture. If culture consisted simply of learning habits from others, it would soon stagnate. For culture to turn cumulative, ideas needed to meet and mate. The ‘cross-fertilisation of ideas’ is a cliché, but one with unintentional fecundity. ‘To create is to recombine’ said the molecular biologist François Jacob. Imagine if the man who invented the railway and the man who invented the locomotive could never meet or speak to each other, even through third parties. Paper and the printing press, the internet and the mobile phone, coal and turbines, copper and tin, the wheel and steel, software and hardware. I shall argue that there was a point in human prehistory when big-brained, cultural, learning people for the first time began to exchange things with each other, and that once they started doing so, culture suddenly became cumulative, and the great headlong experiment of human economic ‘progress’ began. Exchange is to cultural evolution as sex is to biological evolution.

By exchanging, human beings discovered ‘the division of labour’, the specialisation of efforts and talents for mutual gain. It would at first have seemed an insignificant thing, missed by passing primatologists had they driven their time machines to the moment when it was just starting. It would have seemed much less interesting than the ecology, hierarchy and superstitions of the species. But some ape-men had begun exchanging food or tools with others in such a way that both partners to the exchange were better off, and both were becoming more specialised.

Specialisation encouraged innovation, because it encouraged the investment of time in a tool-making tool. That saved time, and prosperity is simply time saved, which is proportional to the division of labour. The more human beings diversified as consumers and specialised as producers, and the more they then exchanged, the better off they have been, are and will be. And the good news is that there is no inevitable end to this process. The more people are drawn into the global division of labour, the more people can specialise and exchange, the wealthier we will all be. Moreover, along the way there is no reason we cannot solve the problems that beset us, of economic crashes, population explosions, climate change and terrorism, of poverty, AIDS, depression and obesity. It will not be easy, but it is perfectly possible, indeed probable, that in the year 2110, a century after this book is published, humanity will be much, much better off than it is today, and so will the ecology of the planet it inhabits. This book dares the human race to embrace change, to be rationally optimistic and thereby to strive for the betterment of humankind and the world it inhabits.

Some will say that I am merely restating what Adam Smith said in 1776. But much has happened since Adam Smith to change, challenge, adjust and amplify his insight. He did not realise, for instance, that he was living through the early stages of an industrial revolution. I cannot hope to match Smith’s genius as an individual, but I have one great advantage over him – I can read his book. Smith’s own insight has mated with others since his day.

Moreover, I find myself continually surprised by how few people think about the problem of tumultuous cultural change. I find the world is full of people who think that their dependence on others is decreasing, or that they would be better off if they were more self-sufficient, or that technological progress has brought no improvement in the standard of living, or that the world is steadily deteriorating, or that the exchange of things and ideas is a superfluous irrelevance. And I find a deep incuriosity among trained economists – of which I am not one – about defining what prosperity is and why it happened to their species. So I thought I would satisfy my own curiosity by writing this book.

I am writing in times of unprecedented economic pessimism. The world banking system has lurched to the brink of collapse; an enormous bubble of debt has burst; world trade has contracted; unemployment is rising sharply all around the world as output falls. The immediate future looks bleak indeed, and some governments are planning further enormous public debt expansions that could hurt the next generation’s ability to prosper. To my intense regret I played a part in one phase of this disaster as non-executive chairman of Northern Rock, one of many banks that ran short of liquidity during the crisis. This is not a book about that experience (under the terms of my employment there I am not at liberty to write about it). The experience has left me mistrustful of markets in capital and assets, yet passionately in favour of markets in goods and services. Had I only known it, experiments in laboratories by the economist Vernon Smith and his colleagues have long confirmed that markets in goods and services for immediate consumption – haircuts and hamburgers – work so well that it is hard to design them so they fail to deliver efficiency and innovation; while markets in assets are so automatically prone to bubbles and crashes that it is hard to design them so they work at all. Speculation, herd exuberance, irrational optimism, rent-seeking and the temptation of fraud drive asset markets to overshoot and plunge – which is why they need careful regulation, something I always supported. (Markets in goods and services need less regulation.) But what made the bubble of the 2000s so much worse than most was government housing and monetary policy, especially in the United States, which sluiced artificially cheap money towards bad risks as a matter of policy and thus also towards the middlemen of the capital markets. The crisis has at least as much political as economic causation, which is why I also mistrust too much government.

(In the interests of full disclosure, I here note that as well as banking I have over the years worked in or profited directly from scientific research, species conservation, journalism, farming, coal mining, venture capital and commercial property, among other things: experience may have influenced, and has certainly informed, my views of these sectors in the pages that follow. But I have never been paid to promulgate a particular view.)

Rational optimism holds that the world will pull out of the current crisis because of the way that markets in goods, services and ideas allow human beings to exchange and specialise honestly for the betterment of all. So this is not a book of unthinking praise or condemnation of all markets, but it is an inquiry into how the market process of exchange and specialisation is older and fairer than many think and gives a vast reason for optimism about the future of the human race. Above all, it is a book about the benefits of change. I find that my disagreement is mostly with reactionaries of all political colours: blue ones who dislike cultural change, red ones who dislike economic change and green ones who dislike technological change.

I am a rational optimist: rational, because I have arrived at optimism not through temperament or instinct, but by looking at the evidence. In the pages that follow I hope to make you a rational optimist too. First, I need to convince you that human progress has, on balance, been a good thing, and that, despite the constant temptation to moan, the world is as good a place to live as it has ever been for the average human being – even now in a deep recession. That it is richer, healthier, and kinder too, as much because of commerce as despite it. Then I intend to explain why and how it got that way. And finally, I intend to see whether it can go on getting better.

CHAPTER 1 A better today: the unprecedented present

On what principle is it, that when we see nothing but improvement behind us, we are to expect nothing but deterioration before us?

THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY

Review of Southey’s Colloquies on Society

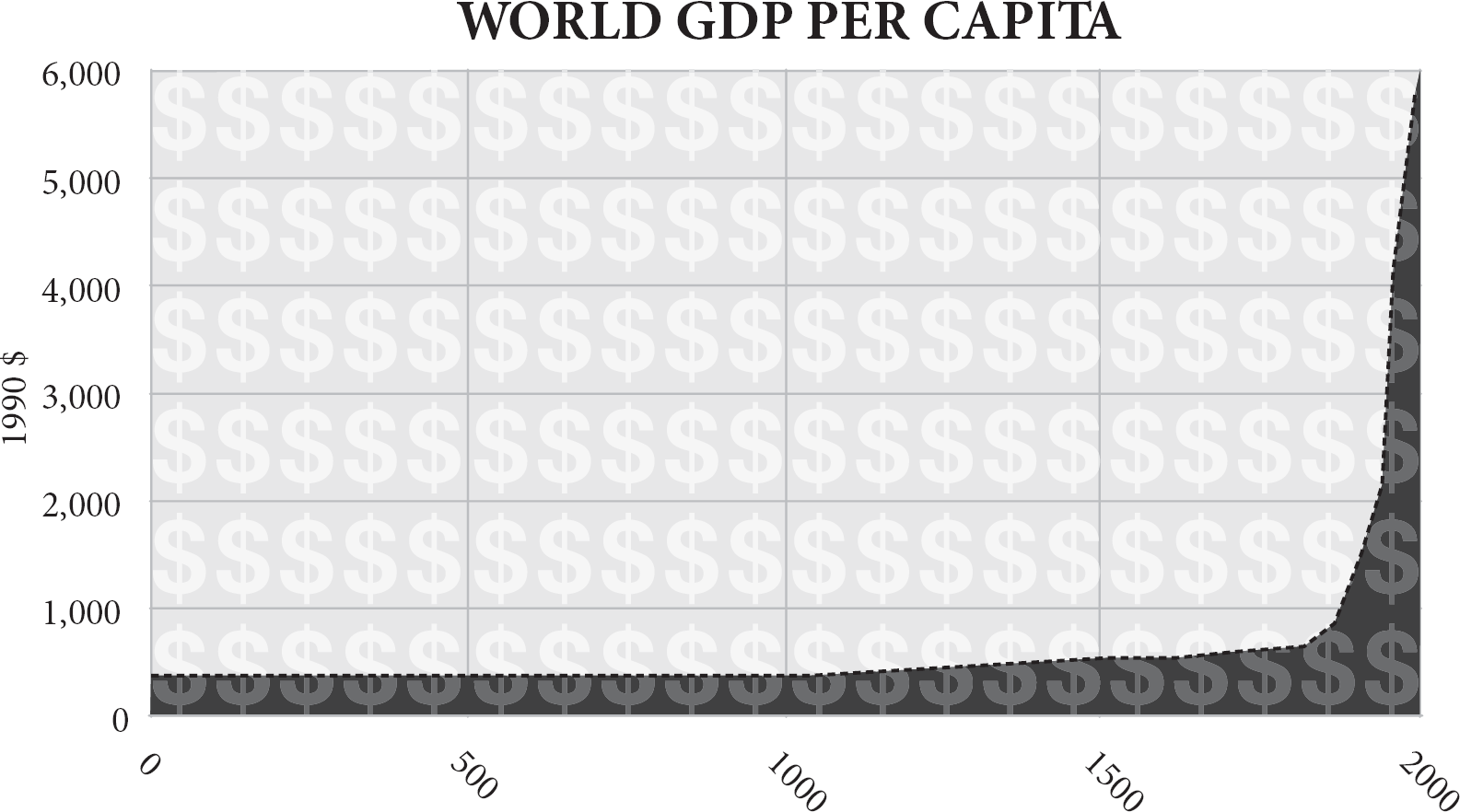

By the middle of this century the human race will have expanded in ten thousand years from less than ten million to nearly ten billion people. Some of the billions alive today still live in misery and dearth even worse than the worst experienced in the Stone Age. Some are worse off than they were just a few months or years before. But the vast majority of people are much better fed, much better sheltered, much better entertained, much better protected against disease and much more likely to live to old age than their ancestors have ever been. The availability of almost everything a person could want or need has been going rapidly upwards for 200 years and erratically upwards for 10,000 years before that: years of lifespan, mouthfuls of clean water, lungfuls of clean air, hours of privacy, means of travelling faster than you can run, ways of communicating farther than you can shout. Even allowing for the hundreds of millions who still live in abject poverty, disease and want, this generation of human beings has access to more calories, watts, lumen-hours, square feet, gigabytes, megahertz, light-years, nanometres, bushels per acre, miles per gallon, food miles, air miles, and of course dollars than any that went before. They have more Velcro, vaccines, vitamins, shoes, singers, soap operas, mango slicers, sexual partners, tennis rackets, guided missiles and anything else they could even imagine needing. By one estimate, the number of different products that you can buy in New York or London tops ten billion.

This should not need saying, but it does. There are people today who think life was better in the past. They argue that there was not only a simplicity, tranquillity, sociability and spirituality about life in the distant past that has been lost, but a virtue too. This rose-tinted nostalgia, please note, is generally confined to the wealthy. It is easier to wax elegiac for the life of a peasant when you do not have to use a long-drop toilet. Imagine that it is 1800, somewhere in Western Europe or eastern North America. The family is gathering around the hearth in the simple timber-framed house. Father reads aloud from the Bible while mother prepares to dish out a stew of beef and onions. The baby boy is being comforted by one of his sisters and the eldest lad is pouring water from a pitcher into the earthenware mugs on the table. His elder sister is feeding the horse in the stable. Outside there is no noise of traffic, there are no drug dealers and neither dioxins nor radioactive fall-out have been found in the cow’s milk. All is tranquil; a bird sings outside the window.

Oh please! Though this is one of the better-off families in the village, father’s Scripture reading is interrupted by a bronchitic cough that presages the pneumonia that will kill him at 53 – not helped by the wood smoke of the fire. (He is lucky: life expectancy even in England was less than 40 in 1800.) The baby will die of the smallpox that is now causing him to cry; his sister will soon be the chattel of a drunken husband. The water the son is pouring tastes of the cows that drink from the brook. Toothache tortures the mother. The neighbour’s lodger is getting the other girl pregnant in the hayshed even now and her child will be sent to an orphanage. The stew is grey and gristly yet meat is a rare change from gruel; there is no fruit or salad at this season. It is eaten with a wooden spoon from a wooden bowl. Candles cost too much, so firelight is all there is to see by. Nobody in the family has ever seen a play, painted a picture or heard a piano. School is a few years of dull Latin taught by a bigoted martinet at the vicarage. Father visited the city once, but the travel cost him a week’s wages and the others have never travelled more than fifteen miles from home. Each daughter owns two wool dresses, two linen shirts and one pair of shoes. Father’s jacket cost him a month’s wages but is now infested with lice. The children sleep two to a bed on straw mattresses on the floor. As for the bird outside the window, tomorrow it will be trapped and eaten by the boy.