Полная версия:

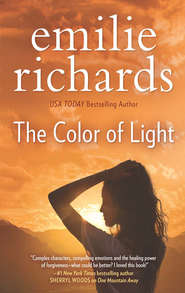

The Color Of Light

The deeper the darkness, the brighter the light

For more than a decade minister Analiese Wagner has felt privileged to lead her parishioners along a well-lit path. Her commitment has never been seriously tested until the frigid night she encounters a homeless family huddling in the churchyard. Offering them shelter in a vacant parish house apartment and taking teenage Shiloh Fowler—a girl desperate to rescue her parents—under her wing, she tests the loyalty and faith of her congregation.

Isaiah Colburn, the Catholic priest who was her first mentor and the man she secretly longed for, understands her struggles only too well. At a crossroads, he’s suddenly reappeared in her life, torn between his priesthood and his growing desire for a future with Analiese.

Divided between love and vows they’ve taken, both must face the possibilities of living very different lives or continuing to serve their communities. With a defeated family’s trust and her own happiness on the line, Analiese must define for herself where darkness ends and light begins.

Praise for the novels of Emilie Richards

“Richards deftly juggles an intriguing thriller with an exploration of domestic violence and reinvention. Still, it’s the quirky, gritty characters in and out of Goddesses Anonymous—all determined to help women in need—who power this tale of forgiveness every step of the way.”

—Publishers Weekly on No River Too Wide

“This is emotional, suspenseful drama filled with hope and love.”

—Library Journal on No River Too Wide

“Portraying the uncomfortable subject of domestic abuse with unflinching thoroughness and tender understanding, Richards’s third installment in the Goddesses Anonymous series offers important insights into a far too prevalent social problem.”

—Booklist on No River Too Wide

“Richards creates a heart-wrenching atmosphere that slowly builds to the final pages, and continues to echo after the book is finished.”

—Publishers Weekly on One Mountain Away

“Complex characters, compelling emotions and the healing power of forgiveness—what could be better? I loved One Mountain Away!”

—New York Times bestselling author Sherryl Woods

“Emilie Richards’s compassion and deep understanding of family relationships, especially those among women, are the soul of One Mountain Away. This rich, multilayered story of love and bitterness, humor, loss and redemption haunts me as few other books have.”

—New York Times bestselling author Sandra Dallas

“When I first began reading One Mountain Away, I wondered where the story was going. A few pages later, I knew precisely where this story was going—straight to my heart. Words that come to my mind are wow, fabulous and beautiful. Definitely a must-read. If any book I’ve ever read deserves to be made into a film, One Mountain Away is it! Kudos to Emilie Richards.”

—New York Times bestselling author Catherine Anderson

Also by Emilie Richards

The Goddesses Anonymous Novels

NO RIVER TOO WIDE

SOMEWHERE BETWEEN LUCK AND TRUST

ONE MOUNTAIN AWAY

The Happiness Key Novels

SUNSET BRIDGE

FORTUNATE HARBOR

HAPPINESS KEY

SISTER’S CHOICE

TOUCHING STARS

LOVER’S KNOT

ENDLESS CHAIN

WEDDING RING

THE PARTING GLASS

PROSPECT STREET

FOX RIVER

WHISKEY ISLAND

BEAUTIFUL LIES

SOUTHERN GENTLEMEN

“Billy Ray Wainwright”

RISING TIDES

IRON LACE

USA TODAY Bestselling Author

The Color of Light

Emilie Richards

www.mirabooks.co.uk

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

Praise for the novels of Emilie Richards

Also by Emilie Richards

Title Page

chapter one

chapter two

chapter three

chapter four

chapter five

chapter six

chapter seven

chapter eight

chapter nine

chapter ten

chapter eleven

chapter twelve

chapter thirteen

chapter fourteen

chapter fifteen

chapter sixteen

chapter seventeen

chapter eighteen

chapter nineteen

chapter twenty

chapter twenty-one

chapter twenty-two

chapter twenty-three

chapter twenty-four

chapter twenty-five

chapter twenty-six

chapter twenty-seven

chapter twenty-eight

chapter twenty-nine

chapter thirty

chapter thirty-one

chapter thirty-two

chapter thirty-three

chapter thirty-four

chapter thirty-five

chapter thirty-six

chapter thirty-seven

chapter thirty-eight

chapter thirty-nine

chapter forty

chapter forty-one

Epilogue

Reader’s Guide

Questions for Discussion

Copyright

chapter one

ANALIESE WAGNER NEEDED to breathe. She was fairly certain she hadn’t inhaled even once during the past hour. Now her head felt three sizes too large, and she was perilously close to her first-ever panic attack. She needed to find a place where she could stand unobserved and fill her lungs and bloodstream with oxygen. Maybe afterward she would be calm enough to get behind the wheel of her Accord and risk life and limb in Asheville’s rush-hour traffic, but not yet.

The church sanctuary was too far away and probably in use. The closest restroom was public. She saw the door to the sexton’s supply closet, opened it, slipped in and closed it behind her. The moment she did, the small room, maybe three feet by five, went dark, but she didn’t care. The air smelled, not unpleasantly, of pine and chlorine.

And she was blessedly alone.

Analiese stood very still, eyes closed, and filled her lungs, releasing the air slowly, and then repeating. She was well acquainted with prayer and meditation, but right now she needed oxygen and silence more.

When her head stopped swimming she rested her face in her hands. Her ministry had come to this. Escaping into the sexton’s closet to inhale poisonous chemicals rather than face even one more member of her staff or congregation.

Long ago the man who had encouraged her to enter seminary had told her there would be moments when she wanted to hang up her clerical collar. He hadn’t told her that she would face most of them alone, and that sometimes God, who was supposed to walk beside her, would wander off, too.

But Isaiah must have known. Who faced loneliness more often than a Catholic priest?

A long moment passed before she straightened, took one more deep breath, and opened the door. No one was in the hall, which made for the best moment of her day. She started toward the front door of the parish house and was only inches from escaping when a familiar voice sounded behind her.

“You’ll be gone for the rest of the day?”

Myra Hudson had been the church administrator longer than Analiese had ministered to the congregation, and she had the gray hair and pursed lips to prove it. The rest of the staff had already gone home, but obviously Myra was soldiering on.

Analiese managed one small smile as she faced her. “Trust me, Myra, my absence will be a gift.”

The other woman’s scowl eased just a fraction. She was twenty years older than Analiese’s thirty-nine, and twenty years more experienced in getting what she wanted. “You have three phone calls to return and a mountain of correspondence. You told me to remind you.”

“A moment of weakness.” Myra didn’t budge, and Analiese lifted her hands in defeat. “I’ll make the calls tonight from home. The mountain can wait until tomorrow.”

“I hope wherever you’re going you plan to walk?”

“And the reason?”

“Because when I looked outside a few minutes ago, a van and a forklift were parked right behind your car.”

“I’m going downtown. To a rally where I’m a featured speaker because somebody in charge actually believed I had something to say.”

“Unlike everyone else you’ve encountered today?”

Analiese let her statement stand.

Myra took pity. “They’re over at the sanctuary. I guess you could put on your friendliest smile and beg them to park somewhere else.”

Analiese didn’t have to ask who “they” were. Radiance Stained Glass from Knoxville, Tennessee, was in town to take measurements for a new rose window in the choir loft, as well as to listen to the council executive committee’s opinion about proposed designs. Analiese had spent the past hour butting heads with the executive committee, but luckily she’d been excused from the next portion of the meeting, since everyone knew exactly what her objections to the designs were and didn’t want to hear them again.

She calculated how long it would take the Radiance crew to move the forklift. She was already late.

“I don’t have my car,” Myra said, taking pity again, “or I would let you borrow it.”

A man spoke. “I have mine.”

Analiese looked up as Ethan Martin joined them from the connecting hallway. She craned her neck to peek behind him. “Please tell me the committee’s still in session,” she said in a low voice.

His smile was warm, his brown eyes sympathetic. “They’re waiting for Radiance. You still have time to get away.”

“Could you possibly get me downtown, Ethan? I’m sure I can find a ride back home afterward.”

“I ought to be at the rally, too. It’s no trouble.”

She met his smile with a more or less genuine one of her own. Ethan was an attractive man in his fifties who really did seem to be an advertisement for the prime of life. Although he attended services from time to time, he wasn’t a formal member of her congregation. He had been a member, well before Analiese’s arrival, but he had resigned after a contentious divorce. His wife, Charlotte Hale, had stayed.

“Why should you be there?” she asked after they said goodbye to Myra and started toward Ethan’s car, wisely parked in the general lot well behind the building.

“I’m working with the Asheville Homeless Network. They asked me to draw up some preliminary sketches for two newly donated lots.”

“You’re becoming Super-Volunteer. I feel guilty I asked you to give your thoughts about the window at today’s meeting.”

“Because I’m already volunteering elsewhere, or because the people on the committee need a few lessons on how to get along?”

Analiese knew Ethan had only agreed to sit in on the rose window committee—who he had represented at the meeting today—as a favor to her. He was an architect whose professional insight was extremely valuable, but even more important, much of the funding for the new window was coming from a bequest Charlotte had made to the church. Ethan and Charlotte had reunited before her death, and the committee was obligated morally, if not legally, to take his opinions and those of Taylor, their daughter, into account.

“The executive committee can be a cranky lot,” she said, thinking what an understatement that was. “I’m sorry I got you into this.”

Afternoon sunshine bronzed the bare limbs of trees that just a month before had flaunted rainbow-colored leaves. November weather in Asheville was unpredictable, but right now the air was balmy, as was the light breeze that pulled wisps of dark hair from the knot she had fashioned on top of her head. As they walked around the parish house, past Covenant Academy, the elite private school the church had founded, she breathed deeply and forced herself to appreciate the parklike surroundings. The grounds had been recently manicured by the garden crew, and pansies and chrysanthemums filled beds along with the stalks of departed hollyhocks nodding in the children’s garden.

That garden sat at the rear of the parish house, nearly out of sight of the street, tended and appreciated by Sunday school classes who grew produce for a local women’s shelter. Analiese had been forced to fight for the patch of land, since the garden was rarely tidy and even more rarely productive. But the children loved working in the sun and getting their hands dirty, and the lessons they learned were invaluable.

As they turned toward the garden she noticed several people strolling to admire the flowers, as well as a family sunning themselves on the grass in the farthest corner. From this distance she didn’t recognize anybody, but they seemed at home. She lifted her hand in acknowledgment as she and Ethan passed the other way. She liked nothing better than to see both the grounds and the building in constant use.

In the parking lot he opened the passenger door of his car and waited until she had settled herself before he closed it. He pulled into traffic and was headed downtown before he spoke.

“So tell me what else went wrong today.”

Although they had never discussed it, Analiese suspected that Ethan had never rejoined the Church of the Covenant because his friendship with her would be altered. He would then be a “lamb in her flock,” an image she wasn’t fond of since none of the church members were vaguely sheeplike. But she liked being Ethan’s friend instead of his spiritual guide.

“You know me well, don’t you?” she said. Her loneliness eased a little.

When a motorcycle cut in front of the car he smoothly switched lanes without missing a beat of conversation. “You held your own, Ana, you really did. But I’m not accustomed to the edge I heard in your voice.”

He’d cut through her defenses so quickly, she didn’t have time to ward off a flashback of the past hours. Waking up alone and lonely in a silent house. Morning prayers interlaced with the usual doubts about her calling. Mind-numbing paperwork no one in seminary had warned her about. Lunch by the bedside of a terminally ill teenager, and finally the meeting with the council executive committee, in which she had been not so subtly reminded of her relative youth and inexperience—as well as the number of parishioners who would prefer a man in their pulpit.

“Some days it doesn’t pay to get out of bed,” she said.

“Especially when you know the committee is lying in wait.”

She understood what he was doing. On their short trip into town he was giving her the opportunity to unload, to tell somebody her troubles for a change. He was a genuinely compassionate man, and a strong one. He would be a logical choice to talk to, except that unloading was not in her nature.

“Tell me about this project for the Homeless Network,” she said, turning the conversational spotlight to him.

After one quick glance, as if to assess whether to coax her, he described his newest undertaking. Several architects were working together to create as many apartment buildings as they could fit into the allotted space and still give occupants attractive, liveable homes to call their own. Ethan wanted to use as much recycled material as possible, and she knew from hearing about the renovations he had done to his own condo that he could do it in style.

She asked questions right up until the moment he dropped her off at the edge of the crowd that was gathering for the rally.

“I’m going to park beside my office, but I’ll meet you back here to take you home,” he said, pointing to a street sign. “In case I can’t find you at the end.”

“You’re really planning to stay?”

“I want to hear what you have to say.”

“Then I’ll treat you to dinner afterward, but it will have to be fast. I have a list of phone calls to make tonight.”

“Ana...maybe you ought to take the night off.”

“Not with the council executive committee gunning for me.”

“After today, you still want to keep your job?”

No good answer occurred to her, but she had to smile. She stepped back and waved him off.

She was quickly drawn into the crowd. When she had agreed to add her comments to those of county officials and other leaders at this rush-hour rally, she hadn’t realized how large the gathering would be. She’d said yes a month ago and then nearly forgotten until a reminder had popped up on her calendar. She was lucky Ethan had driven her and could park in his personal space. Even on a relatively quiet day downtown parking was tough.

She was early—that seemed nearly miraculous since so little had gone well today—and she had a few minutes to unwind before she made her way toward the front. She skirted the crowd and leisurely took in the view.

The scene was Asheville at its finest. Bare-chested, tattooed Gen Xers tossed Frisbees with mutts yapping at their heels. A small group of men in sports coats accompanying women in heels looked as if they had just left downtown offices. Tourists with cameras and retirees dressed for the next round of golf stood side by side with members of the crowd who looked considerably less fortunate. Many of that last group were carrying large backpacks or duffels. One was pushing a shopping cart.

Nobody had as much to gain from a well-attended rally as Asheville’s homeless. The city was working hard to find solutions. Panhandling was now illegal, and of course not everybody was pleased about that, including the man several feet away who was engaged in an angry conversation with a young mother clutching her baby firmly to her chest.

Analiese didn’t think twice. The pair was off to one side of the crowd, in the direction she was walking, and nobody else seemed to be paying attention. The young woman turned and tried to get away, but the man, sporting snakelike dreadlocks, grabbed her shoulder and jerked her backward just as Analiese got close enough to hear him.

“Just some change. You got change, I know you do!”

Analiese arrived just as the young woman, off balance, nearly fell into the man’s arms. “Hey,” she said calmly. “Please let her go. You’re scaring her.”

The man released the young mother with a shove, and she stumbled forward with her baby still clasped against her. He faced Analiese, and up close she saw his eyes were wild, his pupils distended. She was still several feet away but his smell preceded him. Poverty and despair, vomit and urine. She steeled herself not to react, and watched as the young woman found her feet and disappeared into the crowd.

“How ’bout you?” he asked, a grin revealing decaying teeth. “Am I scaring you enough to give me some money?”

“Why don’t I see if I can find somebody with Rescue Ministries to help you? They have better solutions.”

He moved closer. She refused to retreat. In that moment it seemed that she’d been retreating all day. There was no sexton’s closet here, and the time had come to stand her ground.

“I need money!”

Now she smelled alcohol, too, although her first guess had been drugs. She felt and heard movement behind her, and she hoped that reinforcements were closing in.

“I know you do,” she said calmly. “I can get you help. Come with me and we’ll find somebody at the front who can get you dinner and shelter for the night.”

Analiese had plenty of street smarts. Before seminary she had been a broadcast journalist who had done stories in some of San Diego’s meanest neighborhoods, so she was paying close attention to the man’s body language. Unfortunately she had overestimated how drunk he was. She hadn’t expected him to move so quickly. One moment he was an arm’s length away, the next his hands were closing around her neck. She only had time for a quick gasp before her arms came up between his, and she slammed them against his wrists to break his grip.

Furious, he grabbed her again, and this time he shoved her with all his considerable strength.

The fall seemed to take forever, but once she hit the grass, she rolled to her side and tried to push upright. The man who had attacked her was screaming now, as if he’d been tackled. At the moment she couldn’t worry about him. She was still lying on the ground. The people closest to her tried to make room to help, but the crowd surrounding them was expanding and pushing in from the edges. She was jostled as people tried to clear a space. Somebody’s Doc Martens stomped on her hand.

“Give her some room!”

Analiese looked up and just glimpsed a man hovering protectively over her, arm extended. She grabbed his hand gratefully, and he hauled her to her feet.

Once there she tried to thank him, but the crowd surged around her, packing together so tightly that the moment she dropped his hand he disappeared. Police arrived, and she was jostled still more as people made room. Seconds later she glimpsed her attacker being dragged away, screeching about his rights. The police were speaking calmly and trying to convince him to walk on his own, partly, she was sure, because they were surrounded by advocates for the homeless who were watching carefully.

A man in shorts and a tie-dyed T-shirt asked if she was all right, and she nodded, but he wasn’t the one who had rescued her. That man had been taller and dark-haired.

Somebody took her elbow, and she whirled to find Ethan looking down at her. He put his other arm around her and hugged her quickly. “Ana, are you all right?”

She thought she was, although she might sport bruises on her neck and the outline of a heel on her hand as a reminder of the past moments.

“Think so,” she said, shaking her hand back and forth to be sure.

“The police have things under control.” Ethan stepped away a bit and pointed toward the edge of the crowd. “Not his lucky day. He ran right into them after he shoved you.”

“He shouldn’t have gotten out of bed this morning either.”

He smiled warmly, but he continued to hold her elbow to steady her. “Know why he pushed you?”

“Because I was in easy reach and wanted to give him help he’s not ready for. He’s hungry, frightened, tired, angry—”

“You’re being kind. Don’t forget drunk or high. He didn’t seem too steady on his feet.”

“That, too.”

“Let’s see if we can fight our way to the edge.” Ethan guided her in that direction.

“I’d better head for the speakers’ stand.”

“You can make your way up front once we’re out of the throng. Afterward you might want to find the police. You probably should tell them what happened.”

She stayed close to Ethan, letting him clear a path. Out of the worst of the crowd she brushed off her skirt and straightened her blazer. She only rarely wore a clerical collar. Today she wore a burgundy scarf knotted over a light pullover. When she spoke, her role as senior minister of one of the largest Protestant churches in Asheville, North Carolina, should lend enough weight without trappings.

On the other hand, maybe if she had been wearing her collar, the man who had attacked her would have thought better of it.

Definitely an unworthy thought. She had another as she wondered if wearing her collar more often would help with the council executive committee. She sighed and stood still for Ethan’s inspection.

“Am I presentable?”

Another smile. He stretched out his hand and brushed something off her cheek, rubbing it with the tips of his fingers until he was satisfied. “You’re sure you’re okay?”

“He gave me a great opening for my speech. Life on the streets is difficult, even terrifying, and it can have consequences for everybody, the homeless and the onlookers. We need to help people rebuild their lives.”