скачать книгу бесплатно

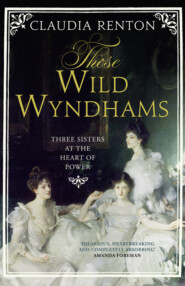

Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power

Claudia Renton

A rich historical biography of ‘those wicked wicked Wyndhams’ – three beautiful, cultured aristocratic sisters born into immense wealth in late Victorian Britain.Mary, Madeline and Pamela – the three Wyndham sisters – were raised surrounded by the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, in a family famed for its bohemian closeness. The liberal upbringing of these handsome, intelligent daughters of a maverick politician and an artistic but emotionally unstable mother prompted one family to forbid their offspring ever to play with ‘those wild Wyndham children’.In adulthood, the sisters became intimate with ‘the Souls’, an intellectual and flirtatious aristocratic set, whose permissive beliefs scandalised society. Eldest and youngest sister became the objects of press fascination as the confidantes of great statesman – Mary of Prime Minister Arthur Balfour; Pamela of the Liberal politician Edward Grey. Madeline had the only happy marriage of the three.Their lives were intertwined with some of the most celebrated and scandalous figures of the day: Oscar Wilde, who fell in love with their cousin Bosie Douglas; Marie Stopes, to whom Pamela became patron; and the iconoclast poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, lover both of Mary and her mother before her. Their lives would be irrevocably devastated by the horrors of the First World War.In their first ever biography, Claudia Renton, drawing on a rich archive of letters, charts these women’s intimate stories in their own voices, from romantic beginnings through the passions and disappointments of womanhood to the tragedy that brought a definitive end to their era, against the backdrop of the political and social events that shaped their age. Those Wild Wyndhams is an unforgettable historical biography that captures the high drama of this grand family against the political and social events that shaped their age.

Dedication (#ulink_e94439ab-1da6-54d1-9e2f-61f774c8dae1)

For Mama.

Always.

Epigraph (#ulink_2932c562-62f2-54e7-90f6-2c9d2917ccc3)

‘La Chanson de Marie-des-Anges’

Y avait un’fois un pauv’gas,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Y avait un’fois un pauv’gas,

Qu’aimait cell’qui n’l’aimait pas.

Elle lui dit: Apport’moi d’main

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Elle lui dit: Apport’moi d’main

L’cœur de ta mèr’ pour mon chien.

Va chez sa mère et la tu

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Va chez sa mère et la tue,

Lui prit l’cœur et s’en courut.

Comme il courait, il tomba,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Comme il courait, il tomba,

Et par terre l’cœur roula.

Et pendant que l’cœur roulait,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Et pendant que l’cœur roulait,

Entendit l’cœur qui parlait.

Et l’cœur lui dit en pleurant,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Et l’cœur lui dit en pleurant:

T’es-tu fait mal mon enfant?

Jean Richepin (1848–1926)

‘Do you know Richepin’s poem about a Mother’s Heart? It means something like this:- “there was a poor wretch who loved a woman who would not love him. She asked him for his Mother’s heart, so he killed his Mother to cut out her heart and hurried off with it to his love. He ran so fast that he tripped and fell, and the heart rolled away. As it rolled it began to speak and asked “Darling child, have you hurt yourself?”’

George Wyndham to Pamela Tennant, 11 March 1912

Contents

Cover (#u92fac752-4e29-5933-96ab-350d581322cf)

Title Page (#u32d4d11a-7dcb-59db-8569-2ea1f13903d4)

Dedication (#ub0f9d869-39d4-54b6-b5f6-335615b7780e)

Epigraph (#ubaf6b94d-e0df-5c1b-ab58-aaaccc6e56b5)

Family Tree (#u34406507-a1a2-58b3-a323-b9d622abb0fd)

Prologue (#u353ba36c-72ab-5bac-a5fd-0e536442ad6e)

1. ‘Worse than 100 boys’ (#u40239673-8dc2-5239-9d0b-7910e5effa83)

2. Wilbury (#u40cd861c-83c3-55a1-a351-db8ef194f96d)

3. ‘The Little Hunter’ (#uc70df969-c6dc-5582-abae-1e6dc93d2a29)

4. Honeymoon (#ubed01ffe-12c7-56bf-8de4-799f21480ca1)

5. The Gang (#u5313104a-1bf6-568c-b56b-bb0fd68b6f3f)

6. Clouds (#u77de2b42-e85b-55fa-9b35-7e570cc3d298)

7. The Birth of the Souls (#u18d96b72-2c89-51d5-a4aa-972150100ab5)

8. The Summer of 1887 (#u7f2889db-ead1-5ea7-afa5-24736ee6b3db)

9. Mananai (#ufe532e70-68bd-55c9-85c3-33adb326013b)

10. Conflagration (#ua2b2beab-a4a3-594d-8a9a-ccafb5968153)

11. The Season of 1889 (#u988bd586-432f-5126-a0f8-028be1d661d8)

12. The Mad and their Keepers (#u4b06ea68-080c-5579-a978-35b8dba3dc4e)

13. Crisis (#ufa0084d4-5f6b-56c3-9f24-7e4825b239f5)

14. India (#u95586be9-d7b0-5c37-bd93-5e82e3283d5c)

15. Rumour (#ua264d5a7-56a5-5e63-a745-c93a50e99517)

16. Egypt (#u39897f18-ec9b-566c-91ba-9e19e9f3f787)

17. The Florentine Drama (#ue7f2d213-ec1b-5f2a-8522-5d80dfab7283)

18. Glen (#u94ce2a14-dd95-5302-ba38-a0b0037ed4c8)

19. The Portrait, War and Death (#uf01cfa08-96e3-5376-93b8-5344e1d8b016)

20. Plucking Triumph from Disaster (#ud85db20b-ce58-5058-ad84-c03e4c675e8b)

21. The 1900 Election (#u9e007646-aaaf-5731-89f3-a81bc20d8240)

22. Growing Families (#u2e8d6877-9708-51f1-8be5-7fd287365d1e)

23. The Souls in Power (#u81c9b1df-754d-535a-a05f-8f4f91ee5df8)

24. Pamela at Wilsford (#u3f5c3075-e07c-5bf0-a2bb-d9fe515be417)

25. Mr Balfour’s Poodle (#u78b25c10-a4ec-5548-a12c-0a8b1818185d)

26. 1910 (#u7b2ab665-3c66-5f9c-a3a6-ff3857fe5946)

27. Revolution? (#u15b84e67-ecf6-5fce-8f4d-4d5f8a7e1376)

28. 1911–1914 (#u350e1ccb-6e6f-5e78-b6f6-69faf442d10e)

29. MCMXIV (#u49555bc5-2786-57c2-bb91-e137216d9563)

30. The Front (#u45aa50dc-12ad-5be4-ab01-ed47ae5c8df7)

31. The Remainder (#u5902931f-0b42-555a-805c-c44ce81908f3)

32. The Grey Dawn (#ubd726ebc-faf1-59a1-8d83-043ac3ce3e53)

33. The End (#u5e267128-d4ed-5004-a2e2-4a4d3b3bbcd7)

Picture Section (#u276f096c-a937-5fe5-a4c6-7ad85efeecf5)

List of Illustrations (#u4b8bc43e-aa3c-5fff-811c-1b0920b7e611)

Notes (#ucd391854-5e13-5477-bbf7-1b91fce09684)

Bibliography (#ufc2d6a8c-aa9e-569d-8591-11e6842c9af2)

Index (#uc10e8aae-aaa2-5f14-9847-0b0351d11c63)

Acknowledgements (#ub1fa0cb0-b93b-5e52-b80d-a8ad7aa7a13c)

About the Author (#uece3f71f-7b7e-550a-8073-a1eb6d4ca147)

Copyright (#ubc6ed34d-1809-5aa2-a3e3-3b305d50a57c)

About the Publisher (#u3a5e0a69-fe3f-50e2-bb33-148da5a3da27)

Prologue (#ulink_ec251a36-21db-5211-b4c6-1e4d94bbf25a)

On a cool February night in 1900, Pamela Tennant, wife of the industrialist Eddy Tennant, was dining at the London townhouse of her brother and sister-in-law, Lord and Lady Ribblesdale. The Season had not quite started, but there was already a smattering of balls. By early summer that smattering would become a deluge, as seemingly every house in Mayfair echoed to the strains of bands and England’s elite waltzed round and round camellia-filled ballrooms in what would prove to be the last year of Victoria’s reign. Thus far, London seemed to have escaped the disgusting yellow smog that had blanketed the city for months the year before, and added to the misery of the swathes affected by a bad strain of influenza that year.

Pamela was not really looking forward to the Season that was to come: or to any Season, for that matter. In the five years since she had married, her refusal to play ball socially had provoked several spats with her sister-in-law. Charty Ribblesdale, one of the audacious Tennant sisters who had launched themselves on to London Society twenty years before, could not understand why Pamela should wilfully clam up when faced with new people. Pamela’s refusal to play by any rules but her own mystified Charty and her sisters Margot and Lucy. They thought it alien to the ethos of the Souls: their fascinating, chattering set who affected insouciant, swan-like ease, no matter how frantically their legs paddled beneath the serene surface.

The delightfully haphazard Mary Elcho, Pamela’s eldest sister, was a leading light of the Souls. Pamela, beautiful, brilliant, a master of the pointed phrase, had it in her to joust with the best of them. But she chose not to. Instead, she professed disdain for ‘those murdered Summers’ of the Season, and openly expressed her preference for Wiltshire, where she caravanned across the Downs in the company of her children.

It was a very peculiar attitude.

The burly American placed next to Pamela also seemed ill at ease among Society’s hubbub. John Singer Sargent, whose Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose had dazzled the Royal Academy over a decade before, was establishing himself as a society portraitist par excellence, but he had little time for his sitters’ chatter. He preferred quiet times in the Gloucestershire village of Broadway with his sisters and nieces – incidentally not far from where Mary Elcho lived at Stanway. ‘He was very nice & simple, & … very shy & not the least like an American,’ Mary’s friend Frances Horner reported to the artist Edward Burne-Jones after meeting Sargent (for Sargent, although an American by parentage, had been born and raised on the Continent), ‘& he wasn’t very like an artist either! … he hated discussing all his great friends … & talking about his pictures.’

Perhaps Charty took a certain pleasure in seating Pamela next to Sargent that evening. A taste of her own medicine – and Charty could justify the placement because Sargent was currently working on a portrait of Pamela and her sisters. It had been commissioned by their father, Percy Wyndham, who, with his wife Madeline, had built Clouds in Wiltshire, a house little over a decade old and already famous as a ‘palace of weekending’.

Pamela, Mary and sweet-natured Madeline Adeane (who so unluckily after a whole brood of girls had finally succeeded in giving birth to a boy only for the premature infant to die the same day) had been sitting to Sargent ever since then.

There was plenty to talk about. No mention was made of the Boer War’s disastrous progress, or Pamela’s elder brother George, Under-Secretary in the War Office, whose triumphant speech in the House of Commons a few weeks before had singlehandedly seemed to redeem the Government’s conduct of the war. All Sargent’s talk was of the portrait. The first sittings had taken place over a year before, in the drawing room of the Wyndhams’ London house, 44 Belgrave Square. Yet just recently, Pamela, in the thick of preparations for one of the tableaux of which she was so fond, received a letter from Percy suggesting that Sargent’s portrait might still not be finished in time for this year’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy. What with the uncertain light at this time of year, and the fact that the Wyndhams would not be in London until after Easter, ‘perhaps this is better’, he concluded.

To Pamela’s mind, this was not better. At this rate, she replied ominously, there was the danger that ‘we shall all be old and haggard before the public sees it’.

Pamela in the flesh made the shortcomings of Pamela in oils all too clear. Sargent told Pamela in his deep, curiously accentless voice (the legacy of his Continental upbringing) that he ‘felt sure’ that Mr Wyndham ‘would not mean it to be as it is’. ‘He is very anxious for some more sittings from me and enquired my plans most pertinaciously,’ Pamela told Percy the next day. Her very presence had seemed to prove an inspiration: ‘“and now I see you oh it must be worked on” – squirming & writhing in his evening suit – “no finish – no finish” – he got quite excited’.