скачать книгу бесплатно

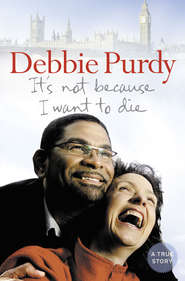

It’s Not Because I Want to Die

Debbie Purdy

Debbie Purdy doesn't want to die. She has far too much to live for. But when the time comes, and the pain is so unbearable that she cannot go on, she wants her husband to be by her side, holding her hand until the end; and she wants to know that he won't be arrested.Debbie Purdy – the face of Britain's right-to-die campaign – suffers from multiple sclerosis. She was diagnosed in 1995 – barely a month after she met her now-husband, Omar Puente, in a bar in Singapore. Within weeks she flew back out to meet Omar and, despite her devastating diagnosis, their relationship grew, as together they travelled Asia doing all the things they loved. When Debbie's health left her no choice but to go back to the UK, Omar followed. They married in 1998.But since the death in 2002 of motor neurone disease sufferer Diane Pretty, who lost her legal battle to have her husband help her take her own life, there has been dark cloud on the horizon for Debbie. She is in pain all the time, with poor circulation, headaches, bed sores and muscle cramps. Once or twice a week, she falls in the shower, presses her panic button and waits for complete strangers to come and help. People pity Debbie, saying she must feel undignified. She disagrees. The only thing she thinks is undignified is having no control over her life or death.When the pain becomes unbearable Debbie wants to be able to choose to end her life, surrounded by her loved ones. In England and Wales this is considered assisting suicide – a crime punishable by up to 14 years imprisonment. Debbie fears as a black foreigner Omar is more likely to face prosecution. All she wants is for the law to be clarified. Then she can make sure Omar never crosses the line.At the end of July 2009 Debbie's long fight was finally rewarded with a court ruling that the current lack of clarity is a violation of the right to a private and family life, and the Director of Public Prosecutions being ordered to issue clear guidance on when prosecutions can be brought in assisted suicide cases, bringing hope and reassurance thousands nationwide.Now, with passion and honesty, Debbie shares her unique story. Told with the joie-de-vivre and grace for which she has become known, Debbie describes her life and her battle.

It’s Not Because I want to Die

Debbie Purdy

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uaf0c4079-4d8a-50eb-8256-9c8269243b0d)

Title Page (#ud7ed494a-7e4e-5ca8-b387-0c122c301a4d)

Preface (#ub3624381-4e42-5737-b2fb-122eb2fec211)

Chapter 1 A Heart in Chains (#uccf9b53d-746e-5277-bede-98528b3bf370)

Chapter 2 Wading through Honey (#ue2ca5f33-9446-5bd2-af0a-dee188d48560)

Chapter 3 ‘Can I Scuba-Dive?’ (#ua19fc413-ff5e-546e-b5ce-20e13544165e)

Chapter 4 My Beautiful Career (#ufb36297c-fe23-5c3a-b104-f6e0a71a2205)

Chapter 5 The Boys from Cuba (#uf5ba360b-4e4b-5883-a968-eaaaec72d84c)

Chapter 6 ‘My Missus’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 ‘Your Grass Is White’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 In Sickness and in Health (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 The Baby Question (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 The View from 4 Feet (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 The Big Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 Let’s Talk about Death (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 The Speeding Train (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 Cuban Roots (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 A Negotiated Settlement (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 A Short Stay in Switzerland (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 Entering the Fray (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 My High-Tech House (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 Some Real-Life, Grown-Up Decisions (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 My Day(s) in Court (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 Round Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 The Tide Turns (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 My Own Little Bit of History (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 Listening to All Sides (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 Lucky Me (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_71b042f4-51a3-5eeb-89fe-c055aba7d131)

‘Jump!’ the instructor yelled.

I obeyed instinctively, then immediately regretted it. What the hell was I doing jumping out of a perfectly good aeroplane 3,000 feet in the air?

‘One thousand and one.’ Training kicked in and I adopted the spread-eagle position, face down. Why am I doing this? What was I thinking?

‘One thousand and two,’ I counted aloud, as we’d been taught, then squinted upwards. Was there any way back into the plane? Surely there had to be. I was still attached by a static line that would pull my chute open. Could I climb up it?

‘One thousand and three.’ The Doc Martens I was wearing were too wide and my feet were shaking, hitting each side so rapidly I thought they might come loose and fall off. I can’t believe I’m doing this, I thought. This is so stupid.

Terror was making me alert to every tiny sensation and I could feel the blood pumping hard through my veins.

‘One thousand and four. Check, shit, malfunction. If your parachute hasn’t deployed by the time you’ve finished counting, you’re in trouble and it’s time to open your secondary chute. Just then, though, I felt a gentle lift and I was pulled upright as my main chute opened. The static line detached and I felt intense relief as I looked up at the billowing white canopy. I’ve never felt so grateful to see anything!

The relief was short-lived because I then looked down and saw that there was nothing between me and the ground. I was falling more slowly, but I was still very definitely falling.

It was deathly quiet up there, and very peaceful. I’d been told to scope out a big yellow cross on the ground and aim for that using the toggles on either side of my chute to change direction, but I couldn’t even see the damn cross. Where the hell was it? I spotted a parachute in front of me and thought I would just aim for that in the hope that it was aiming for the cross. All the guys who were jumping with me that day had seemed cool, calm and confident, so I figured that whoever I was following was going the right way.

I played with the toggles but wasn’t sure how much effect I was having. I kept aiming for the guy ahead and praying that he wasn’t headed for a tree. I still couldn’t see the cross, but by that stage I didn’t care if I was miles away so long as I hit the ground with both feet and didn’t end up hanging from an electricity cable or the upper branches of a tree.

Suddenly the ground was right there and I closed my eyes and went into autopilot, rolling on impact as we’d been taught. When I opened my eyes, I looked down my body to make sure nothing was broken or bleeding and realised my arm was lying on a yellow cross. I’d landed right on top of the target. The guy I had been following was a few hundred yards further on. There was no blood. I was alive and intact.

The instructor who filled out my logbook later wrote, ‘GATW,’ meaning ‘Good all the way.’ I didn’t mention that it was a matter of luck rather than careful control. I felt fantastic. Sheer terror turned to sheer exhilaration and I asked, ‘When can I have another go?’

That was in 1981 and I was 17 years old.

In 1995, fourteen years later, a doctor said to me, ‘When I first saw you, I thought you had MS,’ and inside my head I started to count, one thousand and one.

He organised an MRI scan and a lumbar puncture. One thousand and two.

It was MS and I was in freefall, scared and lonely. One thousand and three.

I walked into the arrivals hall at Singapore’s Changi Airport and saw Omar waiting. I felt a gentle lift and I was upright again – still falling, but I knew I was safe and would be able to control my descent.

I haven’t hit the ground yet. What follows is the story of my journey down so far.

Chapter 1 A Heart in Chains (#ulink_5078ed64-1ba9-5881-8ced-87ab6ac8d244)

In January 1995, at the age of 31, I had recently moved to Singapore and was earning my keep with a pen. (Well, a Mac laptop, but that’s product placement!) I wrote brochure copy for an adventure travel company, and music reviews and features for a number of magazines. A welcome perk of my job was that I got into all the live music clubs free, so of course I was having fun (especially as the bars wouldn’t take money from me for drinks). I shared a flat with an Australian bass player, Belinda, and a Japanese teacher, Tetsu, and was dating my fair share of men without having anyone serious on the scene.

One night Belinda came home from work raving about a band she had seen playing in a club called Fabrice’s. ‘There are seven gorgeous men,’ she said, ‘and they’re explosive on stage. You have to see them.’

‘What are they called?’

‘The Cuban Boys.’

I rang Music Monthly to ask if they’d be interested in a review and they said, ‘Sure.’

I was interested in exploring why foreign musicians were frequently paid so little. I had dreams of doing some investigative journalism to rival All the President’s Men. It was a genuine problem, but I have to admit I was looking for a problem I could bury myself in solving.

I turned up at Fabrice’s on the afternoon of 25 January, toting my notebook and camera, to sit in on the band’s rehearsals. My first thought was that ‘the Cuban Boys’ was a strange name for a group that had seven blokes and three girls in it. My second thought was that Belinda had been exaggerating. Only two of the band members, Emilio and Juan Carlos, were particularly good-looking, while the rest could be described as having ‘good personalities’.

It was the band leader, Omar Puente, who came over to talk to me for the interview, and I thought he seemed a bit Mafioso with his little moustache. He sat opposite me looking very serious and frowning in concentration as we struggled to overcome the language barrier. I spoke English, some Norwegian and a little French, while Omar spoke Spanish, Russian and a little French, so French it was. It took me about twenty minutes to get a single quotable sentence. (I wasn’t 100 per cent sure of how much I understood, but he didn’t read English, so I was unlikely to be sued.)

I picked up the camera and motioned that I wanted to take a picture of them playing. Omar indicated in sign language that they should get changed into their performance outfits, instead of the casual clothes they were wearing.

‘No, don’t bother,’ I said. ‘If you could just play a number for me as you are, that would be fine.’ I motioned towards the stage.

When they started playing, I was instantly impressed. They had a really good sound, and Omar’s violin-playing was fantastic. The repertoire comprised modern and traditional Cuban dance music, but Omar also did a little Bach as a solo and I could hear humour as well as hard work and technique in his playing. On the violin he obviously felt in control; he was a complete master of it.

In the middle of the set, the band launched into a version of ‘La Cucaracha’. The percussionist, Juan Carlos, stood on his chair and put one leg on his conga drum. Then they all stopped playing and did pelvic thrusts in time to the ‘Da-da-da-da dah-dah’ bit in the chorus. It was crude and obscene, but mesmerising.

I came back to Fabrice’s later that night to watch the proper show. The band was not dressed up in their performance shirts, so I figured Omar had been trying to be interesting for the press. (Now I realise it was me he was trying to impress.) He had a very charismatic presence, interacting with the audience and chatting to them between numbers, and moving around the stage with ease. He wasn’t the best-looking band member, but you couldn’t take your eyes off him, mainly because you wanted to see what he would do next. All the band members moved with an easy, natural rhythm, the music was note-perfect, and their set was a huge hit with the regulars at Fabrice’s.

After they finished playing, Omar walked off stage and came over to sit beside me, bringing his friend Rolando, who spoke a bit of English and tried to translate for us.

‘Will you be nice about us in your magazine?’ Omar and Rolando asked. Well, that’s what they were trying to ask.

‘Of course,’ I said. They were so earnest and incredibly entertaining to watch that being anything less than glowing about them would have been like kicking a puppy.

The two of them would feverishly converse in Spanish, words tripping over one another, for several minutes before Omar would try to say something in English.

‘Do you live in Singapore?’ he asked next, and I told him that I did.

Our scintillating conversation floundered a bit when one of Rolando’s girlfriends arrived, but Omar didn’t leave my side for the rest of the evening except to get back on stage and play the second set.

At two or three in the morning, when Singapore was winding down, I was in the habit of stopping at a market for an early breakfast on the way home. I invited Omar to join me so we could continue trying to talk. We borrowed an English–Spanish dictionary, as Rolando didn’t consider his role much fun and the girlfriend clearly was. We walked down to the market and bought bowls of congee (a kind of rice porridge) and some other snacks, and sat at a roadside table to eat.

Now we were away from his job and the band, Omar dropped his earlier, more fatherly persona and started to be flirtatious, touching my arm and offering me bites of his food to sample. It dawned on me that he thought I had asked him on a date. I was just being professional and finishing the interview (I think). He was all smiles and charm until he accidentally bit on a piece of chilli, which ruined his composure. His eyes started watering and he was coughing and spluttering. I handed him a bottle of water to cool his mouth down. Not the most romantic start, and nothing to indicate that this would be the love of my life.

I still hadn’t asked about how much the band was being paid, so I opened the dictionary at the word ‘fee’. Omar signalled, ‘Twenty,’ with his fingers.

‘A day?’ I was horrified.

He nodded.

I thought we were talking about Singapore dollars, which

are worth a lot less than US dollars. Believing that the band was being paid a tiny fraction of what their Singaporean counterparts would earn, my trade-unionist instincts kicked in and my hackles rose. After some frantic investigation, though, I realised that he was telling me how much their daily allowance was, rather than their total fee, and he was talking in US dollars.

I later learned that their income had also been affected by a bad business decision. Most musicians pay an agent fee to whoever got them the job. For this type of long-term contract, it’s usually no more than 15 per cent, and if two or more agents are involved they share the fee. Omar had been a band leader for a short time and his business skills were only marginally better than his language ones. Consequently, his limited (to put it politely) English meant that the Cuban Boys were paying two agents 15 per cent each, which resulted in the ten Cubans receiving just 70 per cent of the fee. It didn’t seem right, but no one person was to blame. The band saved most of their pay to buy instruments, as they would need better equipment to be the next ‘super group’. I could see they would also need better business sense.

We had been speaking at cross-purposes and not even in the same language. It’s hard to make sense when you have to flick through a whole dictionary to locate every word, and even when you find the right one, cultural references mean you still speak at cross-purposes.

After I’d finished eating, I stood up to leave, laying my hands against my cheek to indicate that I needed to sleep. Dawn was breaking and people with normal jobs were starting to make their way to work. Omar asked, ‘Fabrice’s?’ and I realised he was inviting me to come to the gig that evening. I couldn’t make it, so I shook my head and said, ‘Au revoir. A bientôt.’ The Singapore music scene was tiny and I had no doubt we would bump into each other again before too long.

Years later we would still disagree on the details of the day we met. I remember wearing a little black dress, looking sexy and sophisticated, whereas he said I was wearing a white T-shirt and a black skirt. (I know he’s wrong because he says I wasn’t wearing a bra!) I probably had the skirt and T-shirt on in the afternoon for the interview (but with a bra) and the dress on in the evening when I returned to the club for the set. He says it was me who came on to him, whereas I know it was definitely him. He says he was initially attracted by my bottom, and even said so in an Observer article in 1998. (Talking about the size of a girl’s bottom in print must be grounds for divorce!) I wasn’t really that interested in him at first, but I loved the way he played violin. We had the same experience, but we both have different memories of it. Mine, of course, are right!

A couple of days after meeting Omar, Belinda and I went to a jam session at Harry’s Bar – all the musicians in Singapore ended up there on Sundays because if you played you got free drinks – and as soon as we walked in I spotted Omar. He came straight over, but there was an awkward silence because there wasn’t much we could say without someone to translate for us. Normally, you would move on and talk to someone else at this point, but Omar sat down. We listened to the music and had a few drinks. Every time a male friend of mine came over to chat, Omar positioned himself between me and the other man like a bodyguard and watched intently. I wasn’t sure that I wanted this sort of attention, but I felt flattered to be pursued by someone so ‘present’. Gradually I realised that he seemed to have decided I was his.

Back at the flat I shared with Tetsu and Belinda, Belinda quizzed me about him. ‘He looks pretty interested. How about you?’

‘A moot point – we can’t even discuss the weather. He seems nice, but he could be an axe murderer for all I know.’

Belinda couldn’t communicate with him either, and his easy charm and macho display at Harry’s rang warning bells. Besides, her own experience of Latin musicians hardly endeared Omar to her. She herself knew charming Latin men who would quickly make beautiful declarations of love, mean it when they said it, but then leave the room and fall in love with someone else, before finally going home to a wife and kids.

Omar was only a year and a bit older than me – 33 when we met – but he took responsibility for the whole band, and being a band leader is probably the closest thing to being a parent you can get without having to change nappies. Omar could never relax properly at Fabrice’s, where he had nine Cuban kids to look out for. The language barrier was the main problem for them all, but there was always something ready to trip them up. They had a safe refuge on stage. When the band members were together, they could be themselves – crazy and funny, a little wild but always in control – and they had their fearless leader, who was, like any parent, ready to do anything to protect them. Omar loved his band, his music and his life. There was no language barrier with a violin in Omar’s hands.

He may have been the responsible one, the father figure of the Cuban Boys, but it didn’t stop him messing around on stage. One night not long after I’d met Omar, he introduced the band – ‘Juan Carlos on conga, Julio on drum kit…’ – and then he pointed to me in the audience, making everyone turn to look, and said, ‘Allì tienes a la mujer que tiene mi corazón encadenado.’

‘What did he just say?’ I pestered a friend, who was laughing by my side.

He translated: ‘There’s the woman who has my heart in chains.’

I went crimson (something I was to do a lot with Omar). I liked the fact that he was so public about trying to win me over. It was flattering…but still I had my reservations. Latin men and all that.

It’s difficult forming an impression of someone at the best of times, even more so when you don’t speak the same language and you can’t have a conversation, but while watching Omar perform I felt I was getting to know the man. Of all instruments, I think the violin is closest to a voice and I believe you can get a sense of who a person is by the way that they play. Omar’s character came across in his music, and what I saw was someone who was witty and intelligent and caring. It would have taken me years to work that out based on our staccato verbal communications, but his violin-playing told me who he was.

For two and a half weeks I saw Omar nearly every night at Fabrice’s or, earlier in the evening, at one of Singapore’s other music venues (of which there were many). As soon as I arrived, he would stride across the room to kiss me hello and stand by my side, warning off competitors. He’d play his set on stage, then walk straight over the raised area that adjoined the stage to come back and stand by me. He seemed devoted, but still all my friends were saying, ‘Latin musicians? You don’t want to go near one.’

On Valentine’s Day I went for dinner with another man, an engineer who was a friend of the manager of Fabrice’s. We’d known each other for a couple of months and he was very attractive, so when he’d asked me out I’d thought, Great.

He was charming and attentive, and we had a lively conversation over our meal. Then, at midnight, we drifted along to Fabrice’s, because that’s where everyone went in the early hours. As soon as we walked in, though, I spotted Omar and felt uncomfortable. I didn’t want him to see me with another man. He got up on stage to play his set and I led my date over to join a group of friends, making sure I sat at the opposite side of the table from him.

My date was puzzled by my hot–cold attitude and asked, ‘Do you want to dance, Debbie?’