Полная версия:

Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland Before the Romans

Britain B.C.

Life in Britain and Ireland

Before the Romans

Francis Pryor

Dedication

For

TOBY FOX

and

MALCOLM GIBB

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Dates and Periods

Part I: Another Country

Chapter One: In the Beginning

Chapter Two: Neanderthals, the Red ‘Lady’ and Ages of Ice

Chapter Three: Hotting up: Hunters at the End of the Ice Age

Part II: An Island People

Chapter Four: After the Ice

Chapter Five: DNA and the Adoption of Farming

Chapter Six: The Earlier Neolithic (4200-3000 BC)

Chapter Seven: The Earlier Neolithic (4200-3000 BC)

Chapter Eight: The Archaeology of Death in the Neolithic

Part III: The Tyranny of Technology

Chapter Nine: The Age of Stonehenge (the Final Neolithic and Earliest Bronze Age: 2500-1800 BC)

Chapter Ten: Pathways to Paradise (the Mid- and Later Bronze Age: 1800-700 BC)

Chapter Eleven: Men of Iron (the Early Iron Age: 700-150 BC)

Chapter Twelve: Glimpses of Vanished Ways (the Later Iron Age: 200 BC-AD 43, and After)

Afterword

Places to Visit

Notes

Index

P.S. Ideas, interviews & features…

About the author

Portrait

Snapshot

Top Ten Favourite Books

About the book

A Visit to Flag Fen

A Critical Eye

Read on

Have You Read?

If You Loved This, You’ll Like…

Find Out More

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

British ‘Peculiarity’

I decided to write this book because I am fascinated by the story that British prehistory has to tell. By ‘prehistory’ I mean the half-million or so years that elapsed before the Romans introduced written records to the British Isles in AD 43. I could add here that I was tempted to give the book a subtitle suggested to me by Mike Parker Pearson: ‘The Missing 99 Per Cent of British and Irish History’ – but I resisted. In any case, when the Roman Conquest happened, British prehistory did not simply hit the buffers. Soldiers alone cannot bring a culture to a full stop, as Hitler was to discover two millennia later. It is my contention that the influences of British pre-Roman cultures are still of fundamental importance to modern British society. If this sounds far-fetched, we will see that Britain and Ireland’s prehistoric populations had over six thousand years in which to develop their special insular characteristics.

I regard the nations of the British Isles as having more that unites than divides them, and as being culturally peculiar when compared with other European states. I believe that this peculiarity can be traced back to the time when Britain became a series of offshore islands, around 6000 BC. Those six millennia of insular development gave British culture a unique identity and strength that was able to survive the tribulations posed by the Roman Conquest, and the folk movements of the post-Roman Migration Period, culminating in the Danish raids, the Danelaw and of course the Norman Conquest of 1066. It’s in the very nature of British culture to be flexible and to absorb, and sometimes to enliven or transform, influences from outside. Nowhere is this better illustrated than by the historical hybrid that is the English language, which many regard as Britain’s greatest contribution to world culture.

The English language is of course a post-Roman phenomenon that owes much to influences from across the North Sea. Very recent research carried out by a team of scientists from University College (London University) Centre for Genetic Anthropology has shown that the genetic make-up of men now living in English towns mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086 is closely similar to that of men from Norway and the Province of Friesland in northern Holland.1 By contrast, Welshmen from towns on the other side of Offa’s Dyke are genetically very different from English, Dutch and Norwegian males. Does this mean (as some have claimed) that the Anglo-Saxon ‘invasions’ of the early post-Roman centuries wiped out all the native Britons in what was later to become England? I suppose that on the face of it, it could, although I’d like to see more supporting data, because there’s very little actual archaeological evidence for the type of wholesale slaughter such a theory demands. Besides, people have always had to live in settlements and landscapes, which over the centuries acquire their own myths, legends and histories. These in turn may have a profound effect on the incoming component of the local population. It’s not by any means a simple business of one lot in and another lot out.

It is difficult to accept that the entire British cultural heritage of England was wiped out by the Anglo-Saxons. Why, for example, did the newcomers continue to live in the same places as the people they are supposed to have ousted, retaining the earlier place-names? It simply doesn’t make sense, and we should be cautious before adopting all the findings of molecular biology holus-bolus. Culture and population are not synonymous.

Stories have plots and themes, and I have fashioned this book around what I think are the most important. But inevitably I have had to omit an enormous amount of significant material, simply because it fell outside the immediate scope of the story. However, Britain B.C. is not intended to be a textbook, nor is it in any way comprehensive. It’s essentially a narrative – and a personal one at that. This is how I see the story of British prehistory unfolding, and I hold the view that a good narrative should be clear-cut, and not cluttered with fascinating but inessential detail.

What is it about archaeology that fascinates so many people? My own theory is that it’s because it is a tactile, hands-on subject. It isn’t something that exists in the mind alone. Unlike archaeologists, historians rarely get the opportunity to hold something that was last touched by a human hand thousands of years ago. Archaeology is a vivid and direct link to the past, which I believe accounts for the immediacy of its appeal – and to a wide cross-section of society. Over twenty years ago my wife was on a train from London to Huntingdon and found herself sitting next to the British heavyweight boxer Joe Bugner. He was charming and impeccably mannered. At the time he was a national celebrity, but when he discovered that Maisie was an archaeologist he confided that that was something he had always wanted to be. Then this morning I opened The Times to read that the most famous (or infamous) heavyweight of them all, Mike Tyson, had stated: ‘I would like to be an archaeologist.’2 I would imagine that both of them could wield a mattock quite effectively.

Many archaeological books which purport to be non-technical are written as impersonal descriptions of places and objects that are seldom explained, and are united only by the thinnest of themes. As a result, the public may be forgiven for wondering why so much money is currently being spent on a subject that seems to produce such dreary results. ‘Does it really matter?’ is a question I’ve been asked many times in recent years. Of course I think it does. I believe passionately that archaeology is vitally important. Without an informed understanding of our origins and history, we will never place our personal and national lives in a true context. And if we cannot do that, then we are prey to nationalists, fundamentalists and bigots of all sorts, who assert that the revelations or half-truths to which they subscribe are an integral part of human history. It needs to be stated quite clearly: they’re not. In my view, the main lesson of prehistory is that humanity is generally humane, but from time to time is subject to bouts of extreme and unpleasant ruthlessness. Of course one cannot be sure, but I wonder whether this ruthlessness is perhaps a relict survival mechanism that goes back to our origins as a distinct and separate species, known as Homo sapiens. Whatever the cause, the important thing is that it exists, and we should recognise it, not just in others, but within ourselves as well.

Archaeology as an academic discipline is a humanity, and while there are accepted rules for ‘doing’ the subject, it is both impossible and, I believe, undesirable to pretend that archaeologists can provide unbiased and objective truth. We all have our own hobby-horses to bestride, and we might as well ride them in public. So I’ll come clean. My own background is as a field archaeologist – what in the States they refer to as a ‘dirt archaeologist’. It’s a badge I wear with pride, and this book will inevitably reflect that background. Also, for what it’s worth, my views on Creation, religion, ideology and the other related topics I’ll be addressing in this book are essentially pragmatic. I don’t believe in revealed truth, and if I’m forced to seek justification for our existence on this planet, I would turn to Darwin before scripture. He at least provided explanations, even if some of them have been superseded by later findings.

Has its insular peculiarity excluded Britain from other, more important relationships with mainland Europe? In 1972, in his book Britain and the Western Seaways, Professor E.G. Bowen attempted to explain the cultures of western Britain and Ireland in essentially maritime terms.3 He saw close ties between those regions and neighbouring parts of Europe, especially Brittany, Spain and Portugal. In a masterly reworking of the subject, Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and its Peoples (2001), Professor Barry Cunliffe has arrived at much the same view, but revised and extensively enlarged.4 I wouldn’t contest the observations of these two distinguished authors, but I would emphasise the many features that are unique to British and Irish prehistory, ranging from roundhouses and henges to the massive livestock landscapes of the Bronze Age. I would also stress the strong ties that unite east and south-east England to the Low Countries and north-western France; and north-eastern England and eastern Scotland to Scandinavia and the North Sea shores of Germany. I would further suggest that the natural overseas communication routes of at least half of England and Scotland lie to the east, to the North Sea basin and the mainland of north-western Europe.5

This east-west division of Britain also broadly coincides with the lowland and upland zones (respectively) that the great mid-twentieth-century archaeologist Sir Cyril Fox saw as being fundamental to the development of British landscape and culture – what he referred to as the ‘personality of Britain’.6 I tend towards a less closely defined view of these zones. I do not see them as inward-looking or self-referential. Quite the opposite, in fact. To me, the Atlantic/North Sea contrast is just that: it’s a cultural contrast, not a divide, and is one of the key characteristics of the British Isles. It’s a long-term stimulus that has fired the social boilers of Britain and helped ward off complacency.

Before I start in earnest, I’d like to express the hope that by the end of this book you will be as convinced as I am that their pre-Roman cultures have made a distinct contribution to the various national identities of the people of the British Isles. I hope you will also agree that the Ancient Britons have lurked in the twilight zone of history for far too long.

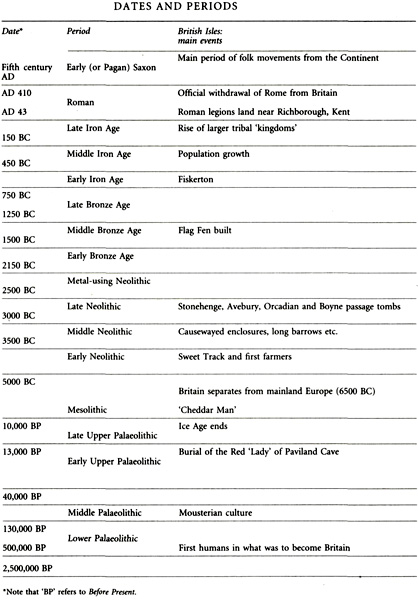

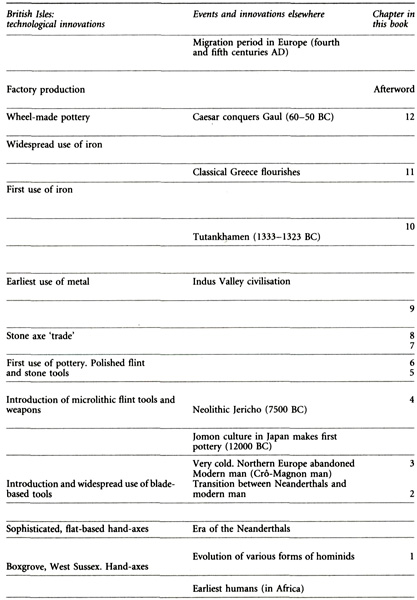

Dates and Periods

CHAPTER ONE In the Beginning

OUR STORY WILL BE about people and time. Human prehistory is such a vast topic that it has proved necessary to divide it up into a series of shorter, more manageable periods. Their origins lie in the birth and development of archaeology itself.

It was a museum curator, C.J. Thomsen, who proposed the Three-Age System of Stone, Bronze and Iron when faced with the challenge of making the first catalogue of the prehistoric collections of the Danish National Museum of Antiquities in Copenhagen. He based his scheme on the relative technological difficulty of fashioning stone, bronze and iron. Iron, of course, requires far greater heat – and controlled heat at that – to smelt and to work than does copper, the principal constituent (with tin) of bronze. Thomsen’s book, A Guide to Northern Antiquities, was published in 1836, with an English translation in 1848. Eleven years later (1859) Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species; by then Thomsen’s scheme had gained wide acceptance.

Although still a young subject, prehistory played an important role in the widespread acceptance of Darwin’s ideas.1 Perhaps that’s why most English prehistorians, myself included, tend to approach our subject from an evolutionary perspective. We probably shouldn’t think in this way, but most of us are products of an education system that places great emphasis on structure, pattern and analytical discipline. Darwin’s views on evolution sit very happily within such a rigorous yet down-to-earth conceptual framework.

In the early and mid-nineteenth century archaeologists in both Britain and France were caught up in the great debate around Noah’s Flood. Working on material found in the gravels of the river Somme, the great French archaeologist Boucher de Perthes published evidence in 1841 that linked stone tools with the bones of extinct animals. He argued that these remains had to predate the biblical Flood by a very long time. It was revolutionary stuff a full eighteen years before the appearance of On the Origin of Species.

I said that Boucher de Perthes published evidence that linked stone tools with the bones of extinct animals. I should have said he published evidence that associated stone tools with the bones of extinct animals. ‘Associated’ is a very important word to archaeologists. It’s code for more than just a link; it can imply something altogether tighter and more intimate. An example might help.

A few years ago we built our house, and whenever I dig the vegetable garden I find pieces of brick and roof-tile in the topsoil. I also find sherds of Victorian willow-pattern plate and fragments of land-drainage pipe which date to the 1920s. Like most topsoils, that in my vegetable garden is a jumble of material that has accumulated over the past few centuries. In archaeological terms these things are only very loosely associated. However, when work eventually finished on the house, I used a digger to excavate a soakaway for a drain, and filled the hole with all manner of builders’ debris left over from the actual building of the house: bricks, tiles, mortar, bent nails and so on. In archaeological terms, my soakaway is a ‘closed group’, and the items found within it are therefore closely associated. To return to the Somme gravels, Boucher de Perthes was able to prove that the bones and the flint tools were from a closed group. This tight association gave his discoveries enormous importance.

It was not long before gravel deposits elsewhere in Europe, including Britain, were producing heavy flint implements like those found in the Somme. They are known as hand-axes, and are the most characteristic artefacts of the earliest age of mankind, the Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age.

Initially, archaeologists, and many others too, were more interested in what these finds stood for – evidence for the true antiquity of mankind – than in the finds themselves. Alliances were formed with pioneering geologists such as Sir Charles Lyell, whose book Principles of Geology, published in 1833, had established the fundamentally important ‘doctrine of uniformity’. This sounds daunting, but isn’t. It’s a grand-sounding way of saying that the natural processes of geology were the same in the past as they are today. So, even ten million years ago rivers wore away at their banks, glaciers scoured out their valleys and every so often volcanoes erupted, covering the countryside around with thick layers of ash and pumice, just as they do today. Put another way, after Lyell nobody could argue that, for example, the highest mountains on earth were covered by the waters of a vast flood just because that accorded with their beliefs.

If one accepted Lyell’s idea of uniformity, it became impossible to deny that the extinct animal bones and the flint tools found by Boucher de Perthes were in existence at precisely the same time – and a very long time ago. By the mid-nineteenth century, Palaeolithic archaeology was on something of a popular roll. No educated household could afford to ignore it. John Lubbock’s book Pre-Historic Times (1865) became a best-seller. Indeed, it was so popular that it’s still possible to pick up a copy quite cheaply. Mine is the fifth edition of 1890, and it cost me a fiver in 1980. It introduced the word ‘prehistory’ to a general audience, albeit with a hyphen, and it didn’t stop short at the Palaeolithic (or Old Stone Age). Lubbock also discussed the later Ages with considerable learning and not a little gusto. I find his enthusiasm infectious, and it isn’t surprising that some of his other books had titles such as The Pleasures of Life (in two volumes, no less). Like many of his contemporaries, Lubbock was able to turn his hand to subjects other than archaeology: his other works include books on insects and flowers aimed at both popular and scientific readers. He was a diverse and extraordinary man.

The first three chapters of this book will be about the earliest archaeological period, the Palaeolithic, or Old Stone Age. The archaeologists and anthropologists who study the Old Stone Age are grappling with concepts of universal, or fundamental, importance. What, for example, are the characteristics that define us as human beings? When and how did we acquire culture, and with it language? Let’s start with the first question; we can deal with the next one in the chapters that follow. I’ll begin by restating it in more archaeological terms: when and where did humankind originate?

The study of genetics has been transformed by molecular biology, but it isn’t always realised just how profound that transformation has been.2 I studied these things in the 1960s, as an undergraduate at university, where I learned that human beings and the great apes were descended from a common ancestor over twenty million years ago. But molecular science has shown this to be wrong. For a start, the time-scale has been compressed, and it is now known that mankind and two of the African great apes, the chimpanzee and the bonobo (a species of pygmy chimp found in the Congo basin),3 share a common ancestor who lived around five million years ago. However, you have to go back thirteen million years to find a common ancestor for man and all the great apes, which include the orang and the gorilla.

There is now a growing body of evidence to suggest that recognisably human beings had evolved in Africa over two and a half million years ago. By ‘recognisably human’ I mean that if one dressed an early hominid, such as Homo rudolfensis (named after a site near Lake Rudolf in Kenya), in a suit and tie, and gave him a shave and a haircut he would, as the old saying goes, probably frighten the children, but not necessarily the horses, should he then decide to take a stroll along Oxford Street. His gait and facial appearance would certainly attract strange looks from those too ill-bred to conceal them; but such frightened sidelong glances aside, he might just be able to complete his shopping unmolested. His appearance in modern clothes would not be as undignified and inappropriate, for example, as that of those poor chimpanzees who until very recently were used to advertise teabags; he was no Frankenstein’s monster. He died out less than two million years ago, and his place was immediately taken by other hominids, including the remarkable Homo erectus, a late form of whose bones were found at a site in Italy dating to a mere 700,000 years ago.4 If Homo erectus took a stroll along Oxford Street, his appearance would attract far less attention than Homo rudolfensis, even if his size and stature would cause most men to step respectfully aside.

When I was a student, the descent of man (people were less twitchy then about using ‘man’ to mean ‘mankind’) was seen as essentially a smooth course, with one branch leading naturally to another. More recently it has become clear that the development actually happened in a more disjointed fashion, with many more false starts and wrong turnings along the way. We now realise that our roots don’t mimic those of a dock or a dandelion, with a single strong central taproot, but are more like those of grasses and shrubs, with many separate strands of greater or lesser length.

The dating of these early bones and the rocks in which they are found depends on various scientific techniques, but not on radiocarbon – more about which later – which is ineffective on samples over about forty thousand years old. Palaeolithic archaeology relies more on the dating of geological deposits, or the contexts in which finds are made, than in dating the finds themselves, as is frequently the case in later prehistory. This often means that dates are established by a number of different, unrelated routes, and that in turn leads to a degree of independence and robustness. So it is possible to say, for example, that early hominids had begun to move out of Africa and into parts of Asia about 1.8 million years ago. When did they move into Europe? That is a very vexed question, involving many hotly disputed sites, dates and theories. But it is probably safe to suggest that man appeared in Mediterranean Europe somewhere around 800,000 years ago, but did not reach northern Europe and the place that was later to become the British Isles until just over half a million years ago.

The most probable reason why there was so long a delay is relatively simple, and has to do with the European climate, which was far less hospitable than that of Africa. It has been suggested that wild animals may have acted as another disincentive, but I find that less plausible: why should European animals have been so very much more fierce than those of Africa? We should also bear in mind that conditions in Europe are less favourable to the survival of archaeological sites than are those in Africa. There is more flowing water around – rivers ceaselessly wear away at their banks; there is a disproportionately larger coastline; and of course there are vastly more people, whose towns, roads and farmlands must have buried or destroyed many Palaeolithic sites. And these very early sites aren’t easy to spot. Unlike the settlements of later prehistory, there’s no pottery, and stone tools are both remarkably rare and easily overlooked, having frequently been stained earthy colours because of their great age. All this suggests that it’s not entirely impossible that the million-year ‘gap’ between the original move out of Africa and the subsequent colonisation of Europe may be more apparent than real.