Полная версия:

The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution and Revenge

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by Harper Perennial in 2006

This book is a revised and updated version of A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War, first published by Fontana Press in 1996, revised and updated from The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939, first published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 1986

First published in Great Britain by William Collins 2016

Copyright © Paul Preston 1986, 1996, 2006, 2016

Paul Preston asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover photograph © Keystone/Getty Images

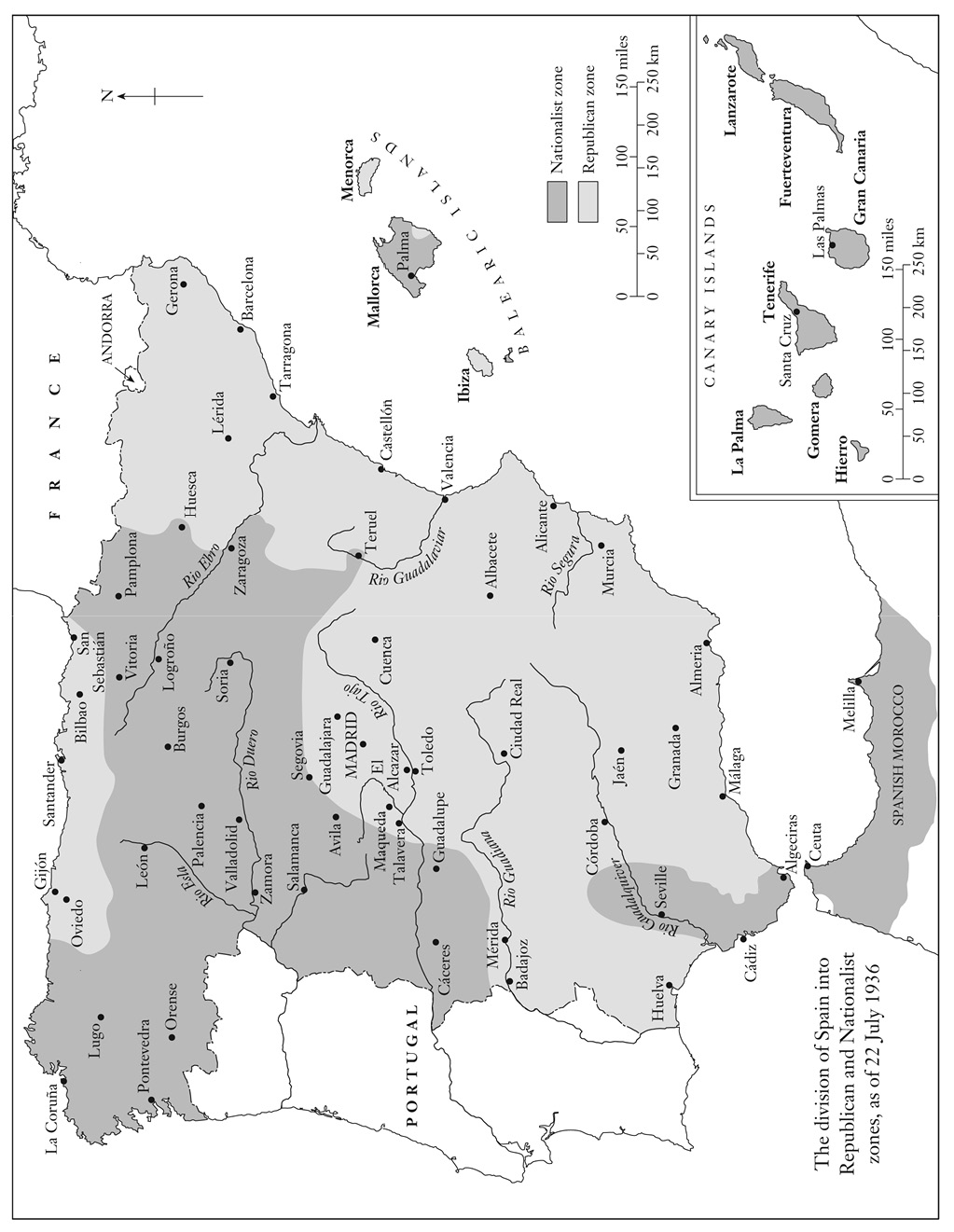

Map © Hardlines

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007232079

Ebook Edition © July 2012 ISBN: 9780007370061

Version: 2017-05-04

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of David Marshall and to the other men and women of the International Brigades who fought and died fighting fascism in Spain.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map of Spain

Preface

Introduction: The Civil War Eighty Years On

1 A Divided Society: Spain Before 1931

2 The Leftist Challenge, 1931–1933

3 Confrontation and Conspiracy, 1934–1936

4 ‘The Map of Spain Bleeds’: From Coup d’État to Civil War

5 ‘Behind the Gentleman’s Agreement’: The Great Powers Betray Spain

6 ‘Madrid is the Heart’: The Central Epic

7 Politics behind the Lines: Reaction and Terror in the City of God

8 Politics behind the Lines: Revolution and Terror in the City of the Devil

9 Defeat by Instalments

10 Franco’s Peace

Epilogue

Principal Characters

Glossary

List of Abbreviations

Bibliographical Essay

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

Also by Paul Preston

Preface

I wrote the first version of this book thirty years ago. My intention then was to provide the new reader with a manageable guide to the bibliographical labyrinth constituted by the fact that the Spanish Civil War has continued to be fought on paper. Even then there had been several thousand books on the Spanish Civil War and many of them were extremely long. Because the flow did not stop, I rewrote the book in 1996 in order to take account of what had been published in the ten years following its first appearance. At that point, I could not have imagined how much more was still to come. Accordingly, in 2006 I wrote a much expanded version in an attempt to come to terms with the very considerable body of scholarship which has been published in Spanish, Catalan, English and other European languages since 1996. It also drew on my own ongoing research on Franco, the Francoist repression and Mussolini’s role in the Spanish Civil War. Over the following years, the flood has not abated, and in this new edition I take account of the most important advances in knowledge about the war as well as drawing on my recent research on the role of Franco, on the murders of civilians behind the lines on both sides, on anti-clerical persecution, on the bombing of Guernica, and on way in which the war ended.

Inevitably, the 2006 edition of the book was much longer – the text 50 per cent longer – than in 1996, and this one adds further material in the light of recent research. Like the three earlier versions, it is interpretative rather than descriptive although even more ample use has been made of contemporary quotation to give a flavour of the period. It remains a book that does not set out to find a perfect balance between both sides. I lived for several years under Franco’s dictatorship. It was impossible not to be aware of the repression of workers and students, the censorship and the prisons. As late as 1975 political prisoners were still being executed. Despite what Franco supporters claim, I do not believe that Spain derived any benefit from the military rising of 1936 and the Nationalist victory of 1939. Many years devoted to the study of Spain of before, during and after the 1930s have convinced me that, while many mistakes were made, the Spanish Republic was an attempt to provide a better way of life for the humbler members of a repressive society. Against such temerity, the revenge taken by Franco and his followers was brutal and pitiless. Accordingly, there is little sympathy here for the Spanish right, but I hope there is some understanding.

My early interest in Spain was stimulated by the postgraduate seminar run at the University of Reading by Hugh Thomas and by Joaquín Romero Maura in Oxford. Over many years, I learned an enormous amount during my friendship with Herbert Southworth who was always prodigal with his hospitality and his knowledge. When I wrote the 1996 version, I was aware of how much I had derived from conversations over many years with Raymond Carr, Norman Cooper, Denis Smyth, Angel Viñas, Julián Casanova, Jerónimo Gonzalo and Martin Blinkhorn. Throughout the 1990s, the historiography of the Spanish Civil War was profoundly changed by the research of Ángela Cenarro, Helen Graham, Gerald Howson, Enrique Moradiellos, Alberto Reig Tapia, Francisco Espinosa Maestre and Ismael Saz. I continue to gain greatly from reading their work and many hours of conversation with them.

My friends Paul Heywood and Sheelagh Ellwood gave me marvellous support during the writing of the first edition. Their role in the second version was assumed by Helen Graham, supplemented by constant interchanges of ideas and information with Hilari Raguer and Francisco Espinosa Maestre. I was also grateful to Francisco Moreno Gómez, Isabelo Herreros and Luis Miguel Sánchez Tostado for help with particular issues. Over subsequent years, I have benefited further from my ongoing interchanges with Linda Palfreeman, Boris Volodarsky, Carmen Negrín, Ángel Viñas, Francisco Espinosa Maestre, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, Javier Cervera Gil, Enrique Líster López, Aurelio Martín Nájera of the Fundación Pablo Iglesias and Sergio Millares of the Fundación Juan Negrín.

My wife Gabrielle is, as ever, my shrewdest critic. With such a team of friends to help, it seems astonishing that any book could still have shortcomings. Unfortunately it does and they are mine.

INTRODUCTION

The Civil War Eighty Years On

On 19 October 2005 the ninety-year-old Santiago Carrillo was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Carrillo was Secretary General of the Partido Comunista de España (PCE) for three decades from 1956 to 1985. He was a crucial, if not uncontroversial, figure in the resistance against Franco’s dictatorship. The granting of the degree (título de doctor) was largely in recognition of his role in the struggle for democracy and his ‘extraordinary merits, and particularly his contribution to the policy of national reconciliation, and his decisive contribution the process of democratic transition in Spain’. Carrillo had come to be widely revered for his moderate and moderating role at a crucial stage in the transition from dictatorship to democracy. However, during the Civil War, at the age of twenty-one, he had been security chief in the Madrid defence junta when large numbers of rightist prisoners were murdered at Paracuellos. Accordingly, the degree ceremony was disrupted by militants chanting ‘¡Paracuellos Carrillo asesino!’ (‘Paracuellos – Carrillo murderer’). It was not the first time that Carrillo had been the target of violent ultra right-wing attacks. Ever since his return to Spain in 1976, he had been the object of abuse for his alleged role in the killings at Paracuellos. On 16 April 2005, at the launch of a book called The Two Spains, by the historian Santos Juliá, where Carrillo was scheduled to speak, the event was interrupted when the bookshop was ransacked by extreme rightists. Barely a week later, a wall adjacent to his apartment block was scrawled with the words ‘this is how the war began and we won’, ‘Carrillo, murderer, we know where you live’ and ‘where is the Spanish gold?’.

These incidents were symptomatic of the way in which the Spanish Civil War retains a burning relevance in contemporary Spain. In geographical and human scale, never mind technological horrors, the Spanish Civil War has been dwarfed by later conflicts. Nonetheless, it has generated around thirty thousand books, a literary epitaph which puts it on a par with the Second World War. In part, that reflects the extent to which, even after 1939, the war continued to be fought between Franco’s victorious Nationalists and the defeated and exiled Republicans. Even more, certainly as far as foreigners were concerned, the survival of interest in the Spanish tragedy was closely connected with the sheer longevity of its victor. General Franco’s uninterrupted enjoyment of a dictatorial power seized with the aid of Hitler and Mussolini was an infuriating affront to opponents of fascism the world over. Moreover, the destruction of democracy in Spain was not allowed to become just another fading remnant of the humiliations of the period of appeasement. Far from trying to heal the wounds of civil strife, Franco worked harder than anyone to keep the war a live and burning issue both inside and outside Spain.

Reminders of Francoism’s victory over international communism were frequently used to curry favour with the outside world. This was most dramatically the case immediately after the Second World War when frantic efforts were made to dissociate Franco from his erstwhile Axis allies. This was done by stressing his enmity to communism and playing down his equally vehement opposition to liberal democracy and socialism. Throughout the Cold War, the irrefutable anti-communism of the Nationalist side in the Civil War was used to build a picture of Franco as the bulwark of the Western system, the ‘Sentinel of the West’ in the phrase coined by his propagandists. Within Spain itself, memories of the war and of the bloody repression which followed it were carefully nurtured in order to maintain what has been called ‘the pact of blood’. The dictator was supported by an uneasy coalition of the highly privileged, landowners, industrialists and bankers; of what might be called the ‘service classes’ of Francoism, those members of the middle and working classes who, for whatever reasons – opportunism, conviction or wartime geographical loyalty – threw in their lot with the regime; and finally of those ordinary Spanish Catholics who supported the Nationalists as the defenders of religion and law and order. Reminders of the war were useful to rally the wavering loyalty of any or all of these groups.

The privileged usually remained aloof from the dictatorship and disdainful of its propaganda. However, those who were implicated in the regime’s networks of corruption and repression, the beneficiaries of the killings and the pillage, were especially susceptible to hints that only Franco stood between them and the revenge of their victims. In any case, for many who worked for the dictator, as policemen, Civil Guards, as humble serenos (night-watchmen) or porteros (doormen), in the giant bureaucracy of Franco’s single party, the Movimiento, in its trade union organization, or in its huge press network, the Civil War was a crucial part of their curriculum vitae and of their value system. They were to make up what in the 1970s came to be known as the bunker, the die-hard Francoists who were prepared to fight for the values of the Civil War from the rubble of the Chancellery. A similar, and more dangerous, commitment came from the praetorian defenders of the legacy of what Spanish rightists refer to broadly as el 18 de julio (from the date of the military rising of 1936). Army officers had been educated since 1939 in academies where they were taught that the military existed to defend Spain from communism, anarchism, socialism, parliamentary democracy and regionalists who wanted to destroy Spain’s unity. Accordingly, after Franco’s death, the bunker and its military supporters were to attempt once more to destroy democracy in Spain in the name of the Nationalist victory in the Civil War.

For these ultra-rightists, Nationalist propaganda efforts to maintain the hatreds of the Civil War were perhaps gratuitous. However, the regime clearly thought it essential for the less partisan Spaniards who rendered Franco a passive support ranging from the grudging to the enthusiastic. Catholics and members of the middle classes who had been appalled by the view of Republican disorder and anti-clericalism generated by the rightist press were induced to turn a blind eye to the more distasteful aspects of a bloody dictatorship by constant and exaggerated reminders of the war. Within months of the end of hostilities, a massive ‘History of the Crusade’ was being published in weekly parts, glorifying the heroism of the victors and portraying the vanquished as the dupes of Moscow, as either squalidly self-interested or the blood-crazed perpetrators of sadistic atrocities. Until well into the 1960s, a stream of publications, many aimed at children, presented the war as a religious crusade against Communist barbarism.

Beyond the hermetically sealed frontiers of Franco’s Spain, the defeated Republicans and their foreign sympathizers rejected the Francoist interpretation that the Civil War had been a battle of the forces of order and true religion against a Jewish–Bolshevik–Masonic conspiracy. Instead, they maintained consistently that the war was the struggle of an oppressed people seeking a decent way of life against the opposition of Spain’s backward landed and industrial oligarchies and their Nazi and Fascist allies. Unfortunately, bitterly divided over the reasons for their defeat, they could not present as monolithically coherent a view of the war as did their Francoist opponents. In a way which weakened their collective voice, but immeasurably enriched the literature of the Spanish Civil War, they were sidetracked into vociferous debate about whether they might have beaten the Nationalists if only they had unleashed the popular revolutionary war advocated by anarchists and Trotskyists as opposed to mounting the conventional war effort favoured by the Republicans, the Socialists and the increasingly powerful Communists.

Thereafter, the debate over ‘war or revolution’ engaged Republican sympathizers unable to come to terms with the leftist defeat. During the Cold War, it was used successfully to disseminate the idea that it was the Stalinist suffocation of the revolution in Spain which led to Franco’s victory. Several works on the Spanish Civil War were sponsored by the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom to propagate this idea. The success of an unholy alliance of anarchists, Trotskyists and Cold Warriors has obscured the fact that Hitler, Mussolini, Franco and Chamberlain were responsible for the Nationalist victory, not Stalin. Nevertheless, new generations have continued to discover the Spanish Civil War, sometimes scouring for parallels, in the light of national liberation struggles in Vietnam, Cuba, Chile and Nicaragua, sometimes just seeking in the Spanish experience the idealism and sacrifice so singularly absent from modern politics.

The relevance of the Civil War to Franco’s supporters and to left-wingers throughout the world does not fully explain the much wider fascination which the Spanish conflict still exercises today. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Korea and Vietnam, it can only seem like small beer. As Raymond Carr has pointed out, compared to Hiroshima or Dresden the bombing of Guernica seems ‘a minor act of vandalism’. Yet it has provoked more savage polemic than virtually any incident in the Second World War. That is not, as some would have it, because of the power of Picasso’s painting but because Guernica was the first total destruction of an undefended civilian target by aerial bombardment. Accordingly, the Spanish Civil War is burned into the European consciousness not simply as a rehearsal for the bigger world war to come, but because it presaged the opening of the floodgates to a new and horrific form of modern warfare that was universally dreaded.

It was because they shared the collective fear of what defeat for the Spanish Republic might mean that men and women, workers and intellectuals, went to join the International Brigades. The left saw clearly in 1936 what for another three years even the democratic right chose to ignore – that Spain was the last bulwark against the horrors of Hitlerism. In a Europe still unaware of the crimes of Stalin, the Communist-organized brigades seemed to be fighting for much that was worth saving in terms of democratic rights and trade union freedoms. The volunteers believed that by fighting fascism in Spain they were also fighting it in their own countries. Hindsight about the sordid power struggles inside the Republican zone between the Communists on the one hand and the Socialists, the anarchists and the quasi-Trotskyist Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) on the other cannot diminish the idealism of the individuals concerned. There remains something intensely tragic about Italian and German refugees from Mussolini and Hitler finally being able to take up arms against their persecutors only to be defeated again.

To dwell on the impact of the horrors of the Spanish war and on the importance of the defence against fascism is to miss one of the most positive factors of the Republican experience – the attempt to drag Spain into the twentieth century. In the drab Europe of the Depression years, what was happening in Republican Spain seemed to be an exciting experiment. Orwell’s celebrated comment acknowledged this: ‘I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.’ The cultural and educational achievements of the Spanish Republic were only the best-known aspects of a social revolution that had an impact on the contemporary world which Cuba in the 1960s and Chile in the 1970s never quite attained. Spain was not only nearby, but its social experiments were taking place in a context of widespread disillusion with the failures of capitalism. By 1945, the fight against the Axis had become linked with the preservation of the old world. During the Spanish Civil War, however, the struggle against fascism was still seen as merely the first step to building a new egalitarian world out of the Depression. In the event, the exigencies of the war effort and internecine conflict stood in the way of the full flowering of the industrial and agrarian collectives of the Republican zone. Nevertheless, there was, and is, something inspiring about the way in which the Spanish working class faced the dual tasks of war against the old order and of construction of the new. The anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti best expressed this spirit when he told the Canadian reporter Pierre Van Paassen, ‘We are not afraid of ruins, we are going to inherit the earth. The bourgeoisie may blast and ruin their world before they leave the stage of history. But we carry a new world in our hearts.’

All of this is perhaps to suggest that interest in the Spanish Civil War is made up of nostalgia on the part of contemporaries of right and left and political romanticism on the part of the young. After all, there is a strong case to be made for presenting the Spanish Civil War as ‘the last great cause’. It was not for nothing that the Civil War inspired the greatest writers of its day in a manner not repeated in any subsequent war. However, nostalgia and romanticism aside, it is impossible to exaggerate the sheer historical importance of the Spanish war. Beyond its climactic impact on Spain itself, the war was very much the nodal point of the 1930s. Baldwin and Blum, Hitler and Mussolini, Stalin and Trotsky all had substantial parts in the Spanish drama. The Rome–Berlin Axis was clinched in Spain at the same time as the inadequacies of appeasement were ruthlessly exposed. It was above all a Spanish war – or rather a series of Spanish wars – yet it was also the great international battleground of fascism and communism. And while Colonel von Richthofen practised in the Basque Country the Blitzkrieg techniques he was later to perfect in Poland, agents of the NKVD endeavoured to re-enact the Moscow trials on the leaders of the POUM because it was made up of dissident anti-Stalinist Marxists and one of its founders, along with Joaquín Maurín, was Andreu Nin, who had once been Trotsky’s secretary in Moscow. The Russians were thwarted by the Spanish Republicans’ insistence on proper judicial procedure.

Nor is the Spanish conflict without its contemporary relevance. The war arose in part out of the violent opposition of the privileged and their foreign allies to the reformist attempts of liberal Republican–Socialist governments to ameliorate the daily living conditions of the most wretched members of society. The parallels with Chile in the 1970s or Nicaragua in the 1980s hardly need emphasizing. Equally, the ease with which the Spanish Republic was destabilized by skilfully provoked disorder had sombre echoes in Italy, and even Spain, in the 1980s. Fortunately, Spanish democracy survived in 1981 the attempts to overthrow it by military men nostalgic for a Francoist Spain of victors and vanquished. The Spanish Civil War was also fought because of the determination of the extreme right in general and the army in particular to crush Basque, Catalan and Galician nationalisms. Spain did not witness ‘ethnic cleansing’ of the kind seen in the civil war in the former Yugoslovia. Nevertheless, Franco made a systematic attempt during and after the war to eradicate all vestiges of local nationalisms, political and linguistic. Although ultimately in vain, the cultural genocide thus pursued by Castilian centralist nationalism has provoked comparisons between the Spanish and Bosnian crises.

In Spain itself, the fiftieth anniversary of the war in 1986 was marked by a silence that was almost deafening. There was a television series and some discreet academic conferences, one of which, held under the title ‘Valencia: Capital of the Republic’, had its publicity poster, designed by the poet and artist Rafael Alberti on the basis of the Republican flag, unofficially, but effectively, banned. There was no official commemoration of the war. That was an act of political prudence on the part of a Socialist government fully aware of the sensibilities of a military caste brought up in the anti-democratic hatreds of Francoism. More positively it was a contribution to what has been called the ‘pact of oblivion’ (pacto del olvido), the tacit, collective agreement of the great majority of the Spanish people to renounce any settling of accounts after the death of Franco. A rejection of the violence of the Civil War and the regime which came out of it overcame any thoughts of revenge.