скачать книгу бесплатно

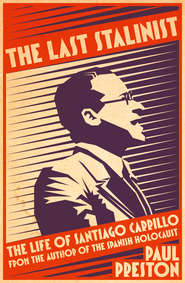

The Last Stalinist: The Life of Santiago Carrillo

Paul Preston

The life of the complex, ruthless adversary of General Franco, whose life spanned much of Spain’s turbulence in the 20th century.From 1939 to 1975, the Spanish Communist Party, effectively lead for two decades by Santiago Carrillo, was the most determined opponent of General Franco’s Nationalist regime. Admired by many on the left as a revolutionary and a pillar of the anti-Franco struggle and hated by others as a Stalinist gravedigger of the revolution, Santiago Carrillo was arguably the dictator’s most consistent left-wing enemy.For many on the right, Carrillo was a monster to be vilified as a mass murderer for his activities during the Civil War. But his survival owed to certain qualities that he had in abundance – a capacity for hard work, stamina and endurance, writing and oratorical skills, intelligence and cunning – though honesty and loyalty were not among them.One by one he turned on those who helped him in his desire for advancement, revealing the ruthless streak that he shared with Franco, and a zeal for rewriting his past. Drawing on the numerous, continuously revised accounts Carillo created of his life, and contrasting them with those produced by his friends and enemies, Spain’s greatest modern historian Paul Preston unravels the legend of a devastating and controversial figure at the heart of 20th century Spanish politics.

(#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

COPYRIGHT (#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2014

Copyright © Paul Preston 2014

Paul Preston asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Cover by Jonathan Pelham based on a photograph © EFE/Lafototeca.com

Source ISBN: 9780007558407

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007558414

Version: 2014-07-16

DEDICATION (#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

In memory of Michael Jacobs

CONTENTS

Cover (#ufd1d0018-7103-5686-828d-f22ba026310e)

Title Page (#u9fa1c8d7-a7cb-5a58-965b-7eab582927e3)

Copyright (#ulink_b34f6b9e-7a54-512a-9e0d-c7e8459dffc2)

Dedication (#ulink_5eee5178-6c0c-5b49-80bd-d2a59d9f0763)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_2d94d62a-801b-5ccf-b3ba-f0df7d290841)

Preface (#ulink_b1360f55-53c9-54f9-836f-a2a2c6d49d8c)

Author’s Note (#ulink_4efe56ca-4938-5f08-bb1c-0bfb0b486793)

1 The Creation of a Revolutionary: 1915–1934 (#ulink_d6f98ef1-817a-5582-8cd0-7384d18cd792)

2 The Destruction of the PSOE: 1934–1939 (#ulink_c78b1866-66ab-5c2c-b45e-ae0302d81f0e)

3 A Fully Formed Stalinist: 1939–1950 (#ulink_b5c36090-8000-5cd0-a932-cd78fe40ea19)

4 The Elimination of the Old Guard: 1950–1960 (#litres_trial_promo)

5 The Solitary Hero: 1960–1970 (#litres_trial_promo)

6 From Public Enemy No. 1 to National Treasure: 1970–2012 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Abbreviations (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Illustration Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

A Note on Primary Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

In a sense, the origins of this book date back to the 1970s when I first began to collect information about the anti-Francoist resistance. At the time and subsequently, I had long conversations with many of the protagonists of the book, including Santiago Carrillo himself. Many of those who shared their opinions and memories with me have since died. However, I would like to put on record my gratitude to them: Santiago Álvarez, Manuel Azcárate, Rafael Calvo Serer, Fernando Claudín, Tomasa Cuevas, Carlos Elvira, Irene Falcón, Ignacio Gallego, Jerónimo González Rubio, Carlos Gurméndez, Antonio Gutiérrez Díaz, K. S. Karol, Domingo Malagón, José Martinez Guerricabeitia, Miguel Núñez, Teresa Pàmies, Javier Pradera, Rossana Rossanda, Jorge Semprún, Enrique Tierno Galvan, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Francesc Vicens and Pepín Vidal Beneyto.

Over the years, I discussed the issues raised in the book with friends and colleagues who have worked on the subject, some of whom played a part in the events related therein. I am grateful for what I have learned from Beatriz Anson, Emilia Bolinches, Jordi Borja, Natalia Calamai, William Chislett, Iván Delicado, Roland Delicado, Carlos García-Alix, Dolores García Cantús, David Ginard i Féron, María Jesús González, Carmen Grimau, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, Enrique Líster López, Esther López Sobrado, Aurelio Martín Nájera, Rosa Montero, Silvia Ribelles de la Vega, Michael Richards, Ana Romero, Nicolás Sartorius, Irène Tenèze, Miguel Verdú and Ángel Viñas Martín.

Finally, this book would not have been possible without the friends who helped with documentation and who read all or part of the text: Javier Alfaya, Nicolás Belmonte Martínez, Laura Díaz Herrera, Helen Graham, Susana Grau, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, Michel Lefevbre, Teresa Miguel Martínez, Gregorio Morán, Linda Palfreeman, Sandra Souto Kustrin and Boris Volodarsky. I am immensely grateful to them all.

PREFACE (#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

This is the complex story of a man of great importance. From 1939 to 1975, the Spanish Communist Party (the Partido Comunista de España, or PCE) was the most determined opponent of the Franco regime. As its effective leader for two decades, Santiago Carrillo was arguably the dictator’s most consistent left-wing enemy. Whether Franco was concerned about the left-wing opposition is another question. However, the lack of a comparable figure in either the anarchist or Socialist movements means that the title belongs indisputably to Carrillo.

Carrillo’s was a life of markedly different and apparently contradictory phases. In the first half of his political career, in Spain and in exile, from the mid-1930s to the mid-1970s, Santiago Carrillo was admired by many on the left as a revolutionary and a pillar of the anti-Franco struggle and hated by others as a Stalinist gravedigger of the revolution. For many on the right, he was a monster to be vilified as a mass murderer for his activities during the Civil War. He came to prominence as a hot-headed leader of the Socialist Youth whose incendiary rhetoric contributed in no small measure to the revolutionary events of October 1934. After sixteen months in prison, he abandoned, and betrayed, the Socialist Party by taking its youth movement into the Communist Party. This ‘dowry’ and his unquestioning loyalty to Moscow were rewarded during the Civil War by rapid promotion within the Communist ranks. Not yet twenty-two years old, he became public order chief in the besieged Spanish capital and acquired enduring notoriety for his alleged role in the episodes known collectively as Paracuellos, the elimination of right-wing prisoners. After the war, he was a faithful apparatchik, who by dint of skill and ruthless ambition rose to the leadership of the Communist Party.

Then, in the course of the second half of his political career, from the mid-1970s until his death in 2012, he came to be seen as a national treasure because of his contribution to the restoration of democracy. From his return to Spain in 1976 until 1981, his skills, honed in the internal power struggles of the PCE, were applied in the national political arena. During the early years of the transition, it appeared as if the interests of the PCE coincided with those of the population. He would be canonized as a crucial pillar of Spanish democracy as a result of his moderation then. He was particularly lauded for his bravery on the night of 23 February 1981 when the Spanish parliament was seized as part of a failed military coup. After that time, his role reverted to that of Party leader and he was undone by generational conflict. Between 1981 and 1985, he presided over the destruction of the Communist Party, which he had spent forty years shaping in his own image. Accordingly, in later life and on his death, he was the object of many tributes and accolades from members of the Spanish establishment ranging from the King to right-wing heavyweights.

The chequered nature of Carrillo’s political career poses the question of whether he was simply a cynical and clever chameleon. In 1974, denying the existence of a personality cult within the PCE, he proclaimed: ‘I will never permit propaganda being made about myself.’1 (#litres_trial_promo) Then, in an interview given two years later, he announced: ‘I will never write my memoirs because a politician cannot tell the truth.’2 (#litres_trial_promo) He had already contradicted the first of these denials by dint of speeches and internal Party reports in which he constructed the myth of a selfless fighter for democracy. Then, in his last four decades, he propagated numerous accounts of his life in countless interviews, in more than ten of the many books that he wrote himself and in two others that he dictated.3 (#litres_trial_promo) In this regard, he shared with Franco a dedication to the constant rewriting and improving of his own life story.

Accordingly, this account of a fascinating life differs significantly from the many versions produced by the man himself which are contrasted here with copious documentation and the interpretations of friends and enemies. There can be little here about Carrillo’s personal life. From the time that he entered employment at the printing works of the Socialist Party aged thirteen until his retirement from active politics in 1991, he seems not to have had much of one. Certainly, his life was dominated by his political activity, but he surrounded accounts about his existence outside politics with a web of contradictory statements and downright untruth.4 (#litres_trial_promo) Despite his apparent gregariousness and loquacity, this is the story of a solitary man. One by one he turned on those who helped him: Largo Caballero, his father Wenceslao Carrillo, Segundo Serrano Poncela, Francisco Antón, Fernando Claudín, Jorge Semprún, Pilar Brabo, Manuel Azcárate, Ignacio Gallego – the list is very long. In his anxiety for advancement, he was always ready to betray or denounce comrades. Such ruthlessness was another characteristic that he shared with Franco. What will become clear is that Carrillo had certain qualities in abundance – a capacity for hard work, stamina and endurance, writing and oratorical skills, intelligence and cunning. Unfortunately, what will become equally clear is that honesty and loyalty were not among them.

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

Although I hope the context always makes the meaning clear, I have used the word ‘guerrilla’ in its original Spanish meaning.

The Spanish word does not mean, as in English usage, ‘a guerrilla fighter’, but rather something closer to ‘campaign of guerrilla warfare’. See here: (#litres_trial_promo) ‘On 20 September, Pasionaria herself had published a declaration hailing the guerrilla as the way to spark an uprising in Spain.’ For the guerrilla fighters themselves, I have used the singular guerrillero or the plural guerrilleros.

1

The Creation of a Revolutionary: 1915–1934 (#u06689297-dae3-577b-8075-89516482163e)

Santiago Carrillo was born on 18 January 1915 to a working-class family in Gijón on Spain’s northern coast. His grandfather, his father and his uncles all earned their living as metalworkers in the Orueta factory. Prior to her marriage, his mother, Rosalía Solares, was a seamstress. His father Wenceslao Carrillo was a prominent trade unionist and member of the Socialist Party who made every effort to help his son follow in his footsteps. As secretary of the Asturian metalworkers’ union, Wenceslao had been imprisoned after the revolutionary strike of August 1917. Indeed, Santiago claimed later that his most profound memory of his father was seeing him regularly being taken away by Civil Guards from the family home. It was there, and later in Madrid, that he grew up within a warm and affectionate extended family in an atmosphere soaked in a sense of the class struggle. Such a childhood would help account for the impregnable self-confidence that was always to underlie his career. He asserted in his memoirs that family was always tremendously important to him.1 (#litres_trial_promo) That, however, would not account for the viciousness with which he renounced in father in 1939. Then, as throughout his life, at least until his withdrawal from the Communist Party in the mid-1980s, political loyalties and ambition would count for far more than family.

Santiago was one of seven children, two of whom died very young. His brother Roberto died during a smallpox epidemic in Gijón that Santiago managed to survive unscathed thanks to the efforts of his paternal grandmother, who slept in the same bed to stop him scratching his spots. A younger sister, Marguerita, died of meningitis only two months after being born. A brother born subsequently was also named Roberto. Coming from a left-wing family, Santiago was not short of rebellious tendencies and, perhaps inevitably, they were exacerbated when he attended Catholic primary school. By then the family had moved to Avilés, 12 miles west of Gijón. For an inadvertent blasphemy, he was obliged to spend an hour kneeling with his arms stretched out in the form of a cross while holding extremely heavy books in each hand. In reaction to the bigotry of his teachers, his parents took him out of the school. Shortly afterwards, the local workers’ centre opened, in the attic of its headquarters, a small school for the children of trade union members. A non-religious teacher was difficult to find and the task fell to a hunchbacked municipal street-sweeper who happened to be slightly more cultured than most of his comrades. Carrillo later remembered with regret the cruel mockery to which he and his fellow urchins subjected the poor man.

Not long afterwards, in early 1924, with Wenceslao now both a full-time trade union official of the General Union of Workers (Unión General de Trabajadores) and writing for El Socialista, the newspaper of the Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, or PSOE), the family moved to Madrid. There, on the exiguous salary that the UGT could afford to pay Wenceslao, they lived in a variety of poor working-class districts. At first, they endured appalling conditions and Santiago later recalled that he witnessed suicides and crimes of passion. In the barrio of Cuatro Caminos, he had the good luck to gain entry to an excellent school, the Grupo Escolar Cervantes.2 (#litres_trial_promo) He later attributed to its committed teachers and its twelve-hour school-day enormous influence in his development, in particular his indubitable work ethic. Whatever criticisms might be made of Carrillo, an accusation of laziness would never be one of them. He was also toughened up by the constant fist-fights with a variety of school bullies.

As a thirteen-year-old his ambition was to be an engineer. However, neither the school nor his family could afford the cost of the examination entry fee for each of the six subjects of the school-leaving certificate. Accordingly, without being able to pursue further studies, he left school with a burning sense of social injustice. Thanks to his father, he would soon embark on a meteoric rise within the Socialist movement. Wenceslao managed to get him a job at the printing works of El Socialista (la Gráfica Socialista). This required him to join the UGT and the Socialist youth movement (Federación de Juventudes Socialistas). As early as November 1929, the ambitious young Santiago, not yet fifteen years of age, published his first articles in Aurora Social of Oviedo, calling for the creation of a student section of the FJS. Helped by the position of his father, he enjoyed a remarkably rapid rise within the FJS, almost immediately being voted on to its executive committee. Of key importance in this respect was the patronage that derived from Wenceslao Carrillo’s close friendship with the hugely influential union leader Francisco Largo Caballero. An austere figure in public life, Largo Caballero was affectionately known as ‘Don Paco’ in the Carrillo household.

The two families used to meet socially for weekly picnics in Dehesa de la Villa, a park outside Madrid. Along with the food and wine, they used to bring a small barrel-organ (organillo). It was used to accompany Don Paco and his wife Concha as they showed off their skill in the typical Madrid dance, the chotis. This family connection was to constitute a massive boost to Santiago’s career within the PSOE. Indeed, the veteran leader had often given the baby Santiago his bottle and felt a paternalistic affection for him that would persist until the Civil War. Later, when he was old enough to understand, Santiago would avidly listen to the conversations of his father and Largo Caballero about the internal disputes within both the UGT and PSOE. There can be little doubt that the utterly pragmatic, and hardly ideological, stances of these two hardened union bureaucrats were to be a deep influence on Santiago’s own political development. Their tendency to personalize union conflicts would also be reflected in his own later conduct of polemics in both the Socialist and Communist parties.3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Santiago was soon publishing regularly in Renovación, the weekly news-sheet of the FJS. This brought him into frequent contact with his almost exact contemporary, the famous intellectual prodigy Hildegart Rodríguez, who as a teenager was already giving lectures and writing articles on sexual politics and eugenics. She spoke six languages by the age of eight and would have a law degree at the age of seventeen. Just as she was rising to prominence within the Socialist Youth, she was shot dead by her mother, Aurora, jealous of Hildegart’s growing independence.

In early 1930, the editor of El Socialista, Andrés Saborit, offered Santiago the chance to leave the machinery of the printing works and work full time in the paper’s editorial offices. It was a promotion that suggested the hands of his father and Don Paco. He started off modestly enough, cutting and pasting agency items and then writing headlines for them. However, he was soon a cub journalist and given the town-hall beat.4 (#litres_trial_promo)

The end of January 1930 saw the departure of the military dictator General Miguel Primo de Rivera. Between then and the establishment of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931, there was intense ferment within the Socialist movement. Certainly, there were as yet few signs of the radicalization that would develop after 1933 and catapult Santiago Carrillo into prominence on the left. The issues in those early days of the Republic revolved around the validity and value of Socialist collaboration with government. In the late 1920s, just as Santiago Carrillo was becoming involved in the Socialist Youth, there were basically three factions within both the Unión General de Trabajadores and the Socialist Party. The most moderate of the three was the group led by the academic Julián Besteiro, president since 1926 of both the party and the union and Professor of Logic at the University of Madrid.5 (#litres_trial_promo) In the centre, at this stage the most realistic although paradoxically, in the context of the time, the most radical, was the group associated with Indalecio Prieto, the owner of the influential Bilbao newspaper El Liberal.6 (#litres_trial_promo) The third, and the one to which Carrillo’s father Wenceslao was linked, was that of Largo Caballero, who was vice-president of the PSOE and secretary general of the UGT.7 (#litres_trial_promo) Given his junior position on the editorial staff of El Socialista, which brought him into daily contact with Besteiro’s closest collaborator, Andrés Saborit, and given his links to Largo Caballero via his father, Santiago Carrillo found it easy to follow the internal polemics even if, to protect his job, he did not yet publicly take sides.

Although extremely conservative, Besteiro seemed to be the most extremist of the three leaders because of his rigid adherence to Marxist theory. The Spanish Socialist movement was essentially reformist and had, with the exception of Besteiro, little tradition of theoretical Marxism. In that sense, it was true to its late nineteenth-century origins among the working-class aristocracy of Madrid printers. Its founder, the austere Pablo Iglesias Posse, was always more concerned with cleaning up politics than with the class struggle. Julián Besteiro, his eventual successor as party leader, also felt that a highly moral political isolationism was the only viable option in the corrupt political system of the constitutional monarchy. In contrast, and altogether more realistically, Indalecio Prieto, who was unusual in that he did not have a trade union behind him, believed that the Socialist movement should do whatever was necessary to defend workers’ interests. His experiences in Bilbao politics had convinced him of the prior need for the establishment of liberal democracy. His early electoral alliances with local middle-class Republicans there led to him advocating a Republican–Socialist coalition as a step to gaining power.8 (#litres_trial_promo) This had brought him into conflict with Largo Caballero, who distrusted bourgeois politics and believed that the proper role of the workers’ movement was strike action. The lifelong hostility of Largo Caballero towards Prieto would eventually be assumed by Santiago Carrillo and, from 1934, become part of his political make-up.

In fact, the underlying conflict between Prieto and Largo Caballero had been of little consequence before 1914. That was largely because in the two decades before the boom prompted by the Great War, prices and wages remained relatively stable in Spain – albeit they were among the highest prices and lowest wages in Europe. As a result, there was little meaningful debate in the Socialist Party over whether to attain power by electoral means or by revolutionary strike action. In 1914, those circumstances began to change. As a non-belligerent, Spain was able to supply food, uniforms, military equipment and shipping to both sides. A frenetic and vertiginous industrial boom accompanied by a fierce inflation reached its peak in 1916. In response to a dramatic deterioration of social conditions, the PSOE and the UGT took part in a national general strike in mid-August 1917. Even then, the maximum ambitions of the Socialists were anything but revolutionary, concerned rather to put an end to political corruption and government inability to deal with inflation. The strike was aimed at supporting a broad-based movement for the establishment of a provisional government that would hold elections for a constituent Cortes to decide on the future form of state. Despite its pacific character, the strike that broke out on 10 August 1917 was easily crushed by savage military repression in Asturias and the Basque Country, two of the Socialists’ three major strongholds – the third being Madrid. In Asturias, the home province of the Carrillo family, the Military Governor General Ricardo Burguete y Lana declared martial law on 13 August. He accused the strike organizers of being the paid agents of foreign powers. Announcing that he would hunt down the strikers ‘like wild beasts’, he sent columns of regular troops and Civil Guards into the mining valleys where they unleashed an orgy of rape, looting, beatings and torture. With 80 dead, 150 wounded and 2,000 arrested, the failure of the strike was guaranteed.9 (#litres_trial_promo) Manuel Llaneza, the moderate leader of the Asturian mineworkers’ union, referring to the brutality of the Spanish colonial army in Morocco, wrote at the time of the ‘African hatred’ during an action in which one of Burguete’s columns was under the command of the young Major Francisco Franco.10 (#litres_trial_promo) As a senior trade unionist who took part in the strike and had experienced the severity of the consequent repression in Asturias, Wenceslao Carrillo was notable thereafter for his caution in any decision that could lead the Socialist movement into perilous conflict with the state apparatus.

The four-man national strike committee was arrested in Madrid. It consisted of the PSOE vice-president, Besteiro, the UGT vice-president, Largo Caballero, Andrés Saborit, leader of the printers’ union and already editor of El Socialista, and Daniel Anguiano, secretary general of the Railway Workers’ Union (Sindicato Ferroviario Nacional). Very nearly condemned to summary execution, all four were finally sentenced to life imprisonment and spent several months in jail. After a nationwide amnesty campaign, they were freed as a result of being elected to the Cortes in the general elections of 24 February 1918. The entire experience was to have a dramatic effect on the subsequent trajectories of all four. In general, the Socialist leadership, particularly the UGT bureaucracy, was traumatized, seeing the movement’s role in 1917 as senseless adventurism. Largo Caballero, like Wenceslao Carrillo, was more concerned with the immediate material welfare of the UGT than with possible future revolutionary goals. He was determined never again to risk existing legislative gains and the movement’s property in a direct confrontation with the state. Both Besteiro and Saborit also became progressively less radical. In different ways, all three perceived the futility of Spain’s weak Socialist movement undertaking a frontal assault on the state. Anguiano, in contrast, moved to more radical positions and was eventually to be one of the founders of the Communist Party.

In the wake of the Russian revolution, continuing inflation and the rising unemployment of the post-1918 depression fostered a revolutionary group within the Socialist movement, particularly in Asturias and the Basque Country. Anguiano and others saw the events in Russia and the failure of the 1917 strike as evidence that it was pointless to work towards a bourgeois democratic stage on the road to socialism. Between 1919 and 1921, the Socialist movement was to be divided by a bitter three-year debate on the PSOE’s relationship with the Communist International (Comintern) recently founded in Moscow. The fundamental issue being worked out was whether the Spanish Socialist movement was to be legalist and reformist or violent and revolutionary. The pro-Bolshevik tendency was defeated in a series of three party congresses held in December 1919, June 1920 and April 1921. In a closely fought struggle, the PSOE leadership won by relying on the votes of the strong UGT bureaucracy of paid permanent officials. The pro-Russian elements left to form the Spanish Communist Party.11 (#litres_trial_promo) Numerically, this was not a serious loss but, at a time of grave economic and social crisis, it consolidated the fundamental moderation of the Socialist movement and left it without a clear sense of direction.

Indalecio Prieto had become a member of the PSOE’s executive committee in 1918.12 (#litres_trial_promo) He represented a significant section of the movement committed to seeking reform through the electoral victory of a broad front of democratic forces. He was appalled when the paralysis within the Socialist movement was exposed by the coming of the military dictatorship of General Primo de Rivera on 13 September 1923. The army’s seizure of power was essentially a response to the urban and rural unrest of the previous six years. Yet the Socialist leadership neither foresaw the coup nor showed great concern when the new regime began to persecute other workers’ organizations. A joint PSOE–UGT note simply instructed their members to undertake no strikes or other ‘sterile’ acts of resistance without instructions from their two executive committees lest they provoke repression. This reflected the determination of both Besteiro and Largo Caballero never again to risk the existence of the UGT in direct confrontation with the state, especially if doing so merely benefited the cause of bourgeois liberalism.13 (#litres_trial_promo)

It soon became apparent that it would be a short step from avoidance of risky confrontation with the dictatorship to active collaboration. In view of the Socialist passivity during his coup, the dictator was confident of a sympathetic response when he proposed that the movement cooperate with his regime. In a manifesto of 29 September 1923, Primo thanked the working class for its attitude during his seizure of power. This was clearly directed at the Socialists. It both suggested that the regime would foster the social legislation longed for by Largo Caballero and the reformists of the UGT and called upon workers to leave those organizations which led them ‘along paths of ruin’. This unmistakable reference to the revolutionary anarcho-syndicalist CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) and the Spanish Communist Party was a cunning and scarcely veiled suggestion to the UGT that it could become Spain’s only working-class organization. In return for collaborating with the regime, the UGT would have a monopoly of trade union activities and be in a position to attract the rank and file of its anarchist and Communist rivals. Largo Caballero was delighted, given his hostility to any enterprise, such as the revolutionary activities of Communists and anarchists, that might endanger the material conditions of the UGT members. He believed that under the dictatorship, although the political struggle might be suspended, the defence of workers’ rights should go on by all possible means. Thus he was entirely open to Primo’s suggestion.14 (#litres_trial_promo) In early October, a joint meeting of the PSOE and UGT executive committees agreed to collaborate with the regime. There were only three votes against the resolution, among them those of Fernando de los Ríos, a distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Granada, and Indalecio Prieto, who argued that the PSOE should join the democratic opposition against the dictatorship.15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Besteiro, like Largo Caballero, supported collaboration, albeit for somewhat different reasons. His logic was crudely Marxist. From the erroneous premise that Spain was still a semi-feudal country awaiting a bourgeois revolution, he reasoned that it was not the job of the Spanish working class to do the job of the bourgeoisie. In the meantime, however, until the bourgeoisie completed its historic task, the UGT should seize the opportunity offered by the dictatorship to have a monopoly of state labour affairs. His argument was built on shaky foundations. Although Spain had not experienced a political democratic revolution comparable to those in England and in France, the remnants of feudalism had been whittled away throughout the nineteenth century as the country underwent a profound legal and economic revolution. Besteiro’s contention that the working class should stand aside and leave the task of building democracy to the bourgeoisie was thus entirely unrealistic since the landowning and financial bourgeoisie had already achieved its goals without a democratic revolution. His error would lead to his ideological annihilation at the hands of extreme leftist Socialists, including Santiago Carrillo, in the 1930s.

Prieto and a number of others within the Socialist Party, if not the UGT, were shocked by the opportunism shown by the leadership of the movement. They accepted that strike action against the army would have been self-destructive, sentimental heroics that would have risked the workers’ movement merely to save the degenerate political system that sustained the monarchy re-established in 1876 after the collapse of the First Republic. However, they could not admit that this justified close collaboration with it. They went largely unheard and the integration of the national leadership with the dictatorship was considerable, the UGT having representatives on several state committees. Wenceslao Carrillo was the Socialist representative on one of the most important, the State Finances Auditing Commission (Consejo Interventor de Cuentas del Estado).16 (#litres_trial_promo) Most UGT sections were allowed to continue functioning and the UGT was well represented on a new Labour Council. In contrast, anarchists and Communists suffered a total clampdown on their activities. In return for refraining from strikes and public protest demonstrations, the UGT was offered a major prize. On 13 September 1924, the first anniversary of the military coup, a royal decree allowed for one workers’ and one employers’ representative from the Labour Council to join the Council of State. The UGT members of the Labour Council chose Largo Caballero. Within the UGT itself this had no unfavourable repercussions – Besteiro was vice-president and Largo himself secretary general. The president, the now ageing and infirm Pablo Iglesias, did not object. However, there was a certain degree of outrage within the PSOE.

Prieto was appalled, rightly fearing that Largo Caballero’s opportunism would be exploited by the dictator for its propaganda value. In fact, on 25 April 1925, Primo did cite Largo Caballero’s presence on the Council of State as a reason for ruling without a parliament, asking rhetorically, ‘why do we need elected representatives?’17 (#litres_trial_promo) When Prieto and De los Ríos wrote to the PSOE executive committee urging the need for distance between party leaders and the military directorate, they were told that Largo Caballero’s nomination was a UGT matter. This was utterly disingenuous since the same individuals made up the executive committees of both bodies which usually held joint deliberations on important national issues. In the face of this dishonesty, Prieto resigned from the committee.18 (#litres_trial_promo) Inevitably, given Largo Caballero’s egoism, his already festering personal resentment of Prieto was cast in stone.19 (#litres_trial_promo) It would continue throughout the years of the Republic and into the Civil War and would later influence Santiago Carrillo. When his own political positions came to be opposed to those of Prieto from late 1933 onwards, Carrillo would adopt an aggressive hostility towards him that fed off that of his mentor. This was to be seriously damaging to the Republic at the time and to the anti-Francoist cause after the Civil War.

Within four years of the establishment of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship, the economic boom that had facilitated Socialist collaboration was coming to an end. By the beginning of 1928, significant increases in unemployment were accompanied by growing evidence of worker unrest. The social democratic positions of Prieto and De los Ríos were gaining support. They constituted just one of the three tendencies within the Socialist movement whose divisions had been exacerbated by the dictatorship. The deteriorating economic situation confirmed both Prieto and the deeply reformist and rigidly orthodox Marxist Besteiro and Saborit in their respective positions. However, as the recession changed the mood of the Socialist working masses, it inevitably affected the views of the pragmatic trade unionists under Largo Caballero. That necessarily included his lieutenant Wenceslao Carrillo. They had gambled on securing for the UGT a virtual monopoly within the state industrial arbitration machinery, but it had done little to improve recruitment. Indeed, the small overall increase in membership was disappointing relative to the UGT’s privileged position. Moreover, there was a drop in the number of union members paying their dues in two of the UGT’s strongest sections, the Asturian miners and the rural labourers.20 (#litres_trial_promo) Always sensitive to shifts in rank-and-file feeling, Largo Caballero began to rethink his position and reconsider the advantages of a rhetorical radicalism. Since Wenceslao Carrillo spoke freely with his thirteen-year-old son, it is to be supposed that the beginnings of Santiago’s own extremism in the period between 1933 and 1935 may be traced to this period. The difference would be that he believed in revolutionary solutions whereas Largo Caballero merely used revolutionary language in the hope of frightening the bourgeoisie.

At the Twelfth Congress of the PSOE, held in Madrid from 9 June to 4 July 1928, Prieto and others advocated resistance against the dictatorship, and a special committee created to examine the party’s tactics rejected collaboration by six votes to four. Nevertheless, the wider Congress majority continued to support collaboration. This was reflected in the elections for party offices at the Congress and for those in the UGT at its Sixteenth Congress, held from 10 to 15 September. Pablo Iglesias had died on 9 December 1925. Having already replaced him on an interim basis, Besteiro was now formally elected to succeed him as president of both the PSOE and the UGT. All senior offices went to followers either of Besteiro or of Largo Caballero. In the PSOE, Largo Caballero was elected vice-president, Saborit treasurer, Lucio Martínez Gil of the land workers secretary general and Wenceslao Carrillo minutes secretary. In the UGT, Saborit was elected vice-president, Largo Caballero secretary general and Wenceslao Carrillo treasurer.21 (#litres_trial_promo) Despite a growth in unemployment towards the end of the decade and increasing numbers of strikes, as late as January 1929 Largo Caballero was still arguing against such direct action and in favour of government legislation.22 (#litres_trial_promo) However, with the situation deteriorating, it can have been with little conviction. Opposition to the regime was growing in the universities and within the army. Intellectuals, Republicans and even monarchist politicians protested against abuses of the law. The peseta was falling and, as 1929 advanced, the first effect of the world depression began to be felt in Spain. The Socialists were gradually being isolated as the dictator’s only supporters outside his own single party, the Unión Patriótica.

Matters reached a head in the summer when General Primo de Rivera offered the UGT the chance to choose five representatives for a proposed non-elected parliament to be known as the National Assembly. When the National Committees of the PSOE and the UGT held a joint meeting to discuss the offer on 11 August, Largo Caballero called for rejection of the offer while Besteiro, with support from Wenceslao Carrillo, was in favour of acceptance. Largo Caballero won, having changed his mind about collaboration with the dictatorship for the purely pragmatic reason that the tactic was now discredited in the eyes of the rank and file.23 (#litres_trial_promo) Since Besteiro regarded the dictatorship as a transitional stage in the decomposition of the monarchical regime, he thought it logical to accept the privileges offered by the dictator. According to his simplistically orthodox Marxist analysis, the monarchy had to be overthrown by a bourgeois revolution, and therefore the job of the UGT and PSOE leadership was to keep their organizations intact until they would be ready to work for socialism within a bourgeois regime.24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Largo Caballero made a number of speeches in late 1929 and early 1930 which indicated a move towards the stance of Prieto and De los Ríos in favour of Socialist cooperation with middle-class Republicans against the monarchy.25 (#litres_trial_promo) Pragmatic and opportunist, concerned always with the material interests of the Socialist movement and the maintenance of the union bureaucracy’s control over the rank and file, he was prone to sudden and inconsistent shifts of position. Primo de Rivera resigned on 28 January 1930 to be replaced for three weeks by General Dámaso Berenguer. Just at the moment that the young Santiago Carrillo was being promoted from the printing works of El Socialista to the editorial staff, the Socialists seemed to be in a strong position despite the failures of collaboration. Other left-wing groups had been persecuted. Right-wing parties had put their faith in the military regime and allowed their organizations, and more importantly their networks of electoral falsification, to fall into decay. Inevitably, the growing opposition to the monarchy looked to the Socialists for support. With the Socialist rank and file increasingly militant, especially as they followed the examples set by the resurgent anarcho-syndicalist CNT and, to a much lesser extent, by the minuscule Communist Party, Largo Caballero moved ever more quickly towards Prieto’s position. The Director General of Security, General Emilio Mola, was convinced that what he called the CNT’s ‘revolutionary gymnastics’ were forcing the UGT leadership to follow suit for fear of losing members.26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Prieto and De los Ríos attended a meeting of Republican leaders in San Sebastián on 17 August. From this meeting emerged the so-called Pact of San Sebastián, the Republican revolutionary committee and the future Republican–Socialist provisional government. The National Committees of the UGT and the PSOE met on 16 and 18 October (respectively) to discuss the offer of two ministries in the provisional government in return for Socialist support, with a general strike, for a coup d’état. The Besteiristas were opposed but the balance was swung by Largo Caballero. His change of mind reflected that same opportunistic pragmatism that had inspired his early collaboration with, and later opposition to, the dictatorship. He said himself at the time, ‘this is a question not of principles but of tactics’.27 (#litres_trial_promo) In return for UGT support for a military insurrection against the monarchy, the Republicans’ original offer was increased to three ministries. When the executive committee of the PSOE met to examine the offer, it was accepted by eight votes to six. The three Socialist ministers in the provisional government were designated as Largo Caballero in the Ministry of Labour, and, to the latter’s barely concealed resentment, Prieto in the Ministry of Public Works and De los Ríos in Education.28 (#litres_trial_promo)

All of these issues were discussed by Santiago and his father as they walked home each day from Socialist headquarters in Madrid, housed in the members’ meeting place, the Casa del Pueblo. Inevitably, Wenceslao propounded a version that entirely justified the positions of Largo Caballero. There can be little doubt that, at least from this time onwards, if not before, the young Santiago Carrillo began to venerate Largo Caballero and to take his pronouncements at face value.29 (#litres_trial_promo) It would not be until the early months of the Civil War that he would come to realize the irresponsible opportunism that underlay his hero’s rhetoric. Now, however, in his early teens and on the threshold of his political career, he absorbed the views of these two mentors, his father and Largo Caballero. These close friends were both practical union men whose central preoccupation was always to foster the material welfare of the Socialist Unión General de Trabajadores. They put its finances and its legal position, its recruitment and the collection of its members’ dues and subscriptions ahead of all theoretical considerations. In long conversations with his father and at gatherings of both families, the young Santiago learned key lessons that were to be apparent in his later career. He learned about pragmatism and opportunism, about how an organization works, about how to set up and pack meetings and congresses to ensure victory. He learned that, while theoretical polemics might rage, these organizational lessons were the immutable truths that mattered. They were to be of inestimable value to him in his rise to power within the Communist Party, within the internal struggles that divided the Party throughout the 1960s and in the transition to, and the early years of, democracy in Spain. Parallels might be drawn between the collaboration of Largo Caballero’s UGT with the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in the 1920s and Santiago’s own moderation during the transition to democracy symbolized by his adoption of the monarchist flag in 1977.

Apart from sporadic strike action, the Socialist movement had taken no official part in the varied resistance movements to the dictatorship, at least until its later stages. The Pact of San Sebastián changed things dramatically. The undertaking to help with the revolutionary action would further divide both the UGT and the PSOE. Strike action in support of a military coup was opposed by Besteiro, Saborit and their reformist supporters within the UGT, Trifón Gómez of the Railway Workers’ Union and Manuel Muiño, president of the Casa del Pueblo, where Socialist Party and union members would gather. Largo Caballero and Wenceslao Carrillo were firmly in favour. Santiago was an enthusiastic supporter of revolutionary action, having just read his first work by Lenin, the pamphlet Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, which outlined the theoretical foundation for the strategy and tactics of the Bolshevik Party and criticized the role of the Mensheviks during the 1905 revolution. He equated the position of Besteiro with that of the Mensheviks. He was also influenced by both his father and Largo Caballero. Inevitably, he faced an uncomfortable time in the office that he shared with Saborit at the Gráfica Socialista.30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Santiago saw his first violent action in mid-November 1930. On 12 November, the collapse of a building under construction in the Calle Alonso Cano of Madrid killed four workers and badly injured seven others. The large funeral procession for the victims was attacked by the police, and in consequence the UGT, seconded by the CNT, called a general strike for 15 November. Santiago was involved in the subsequent clashes with youths who were selling the Catholic newspaper El Debate, the only one that had ignored the strike call.31 (#litres_trial_promo) He was also involved peripherally when the UGT participated, in a small way, in the revolutionary movement agreed upon in October. It finally took place in mid-December. The Republican ‘revolutionary committee’ had been assured that the UGT would support a military coup with a strike. Things were complicated somewhat when, in the hope of sparking off a pro-Republican movement in the garrisons of Huesca, Zaragoza and Lérida, Captains Fermín Galán, Angel García Hernández and Salvador Sediles rose in Jaca (Huesca) on 12 December, three days before the agreed date. Galán and García Hernández were shot after summary courts martial on 14 December which led to the artillery withdrawing from the plot. And, although forces under General Queipo de Llano and aviators from the airbase at Cuatro Vientos went ahead, they realized that they were in a hopeless situation when the expected general strike did not take place in Madrid.32 (#litres_trial_promo)

This was largely the consequence of the scarcely veiled opposition of the Besteirista leadership. Madrid, the stronghold of the Besteiro faction of the UGT bureaucracy, was the only important city where there was no strike. That failure was later the object of bitter discussion at the Thirteenth Congress of the PSOE, in October 1932, where the Besteiristas in the leadership were accused of dragging their feet, if not actually sabotaging the strike. When, on 10 December 1930, Julio Álvarez del Vayo, one of the Socialists involved in the conspiracy, tried to have the revolutionary manifesto for the day of the proposed strike printed at the Gráfica Socialista, Saborit refused point-blank. General Mola, apparently on the basis of assurances from Manuel Muiño, was confident on the night of the 14th that the UGT would not join in the strike on the following day. Despite being given the strike orders by Largo Caballero, Muiño did nothing. This was inadvertently confirmed by Besteiro when he told the Thirteenth Congress of the PSOE that he had finally told Muiño to go ahead only after having been pressed by members of the Socialist Youth Federation to take action. One of those FJS members was Santiago Carrillo, whose later account casts doubt on that of Besteiro. The fact is that none of the powerful unions controlled by the Besteirista syndical bureaucracy stopped work. The group from the FJS, including Santiago Carrillo (who had been given a pistol which he had no clue how to use), had gone to the Conde Duque military garrison on the night of 14 December in the hope of joining the rising that never materialized. After being dispersed by the police, but seeing planes dropping revolutionary propaganda over Madrid, this group of teenage Socialists went to the Casa del Pueblo at Calle Carranza 20 to demand to know why there was no strike. They got no explanation but only a severe dressing-down from Besteiro himself.33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Not long afterwards, the barely sixteen-year-old Santiago was elected on to the executive committee of the FJS. In the wake of the failed uprising in December, the government held municipal elections on 12 April 1931 in what it hoped would be the first stage of a controlled return to constitutional normality. However, Socialists and liberal middle-class Republicans swept the board in the main towns while monarchists won only in the rural areas where the social domination of the local bosses, or caciques, remained intact. On the evening of polling day, as the results began to be known, people started to drift on to the streets of the cities of Spain and, with the crowds growing, Republican slogans were shouted with increasing excitement. Santiago Carrillo and his comrades of the FJS took part in demonstrations in favour of the Republic which were fired on by Civil Guards on the evening of 12 April and dispersed by a cavalry charge the following day.34 (#litres_trial_promo) Nevertheless, General José Sanjurjo, the commander of the Civil Guard, made it clear that he was not prepared to risk a bloodbath on behalf of the King, Alfonso XIII. General Dámaso Berenguer had been replaced as head of the government by Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar. Berenguer, now Minister of War, was equally pessimistic about army morale but was constrained by his loyalty to the King. Despite his misgivings, on the morning of 14 April Berenguer told Alfonso that the army would fight to overturn the result of the elections. Unwilling to sanction bloodshed, the King refused, believing that he should leave Spain gracefully and thereby keep open the possibility of an eventual return.35 (#litres_trial_promo) As news of his departure spread, a euphoric multitude, including Santiago Carrillo, gathered in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol to greet the Republican–Socialist provisional government.

Despite the optimism of the crowds that danced in the streets, the new government faced a daunting task. It consisted of three Socialists and an ideologically disparate group of petty-bourgeois Republicans, some of whom were conservatives, some idealists and several merely cynics. That was the first weakness of the coalition. They had shared the desire to rid Spain of Alfonso XIII, but each then had a different agenda for the future. The conservative elements wanted to go no further than the removal of a corrupt monarchy. Then there was the Radical Party of Alejandro Lerroux whose principal ambition was merely to enjoy the benefits of power. The only real urge for change came from the more left-leaning of the Republicans and the Socialists, whose reforming objectives were ambitious but different. They both hoped to use state power to create a new Spain. However, that required a vast programme of reform which would involve weakening the influence of the Catholic Church and the army, establishing more equitable industrial relations, breaking the near-feudal powers of the owners of the latifundios, the great estates, and satisfying the autonomy demands of Basque and Catalan regionalists.

Although political power had passed from the oligarchy to the moderate left, economic power (ownership of the banks, industry and the land) and social power (control of the press, the radio and much of the education system) were unchanged. Even if the coalition had not been hobbled by its less progressive members, this huge programme faced near-insuperable obstacles. The three Socialist ministers realized that the overthrow of capitalism was a distant dream and limited their aspirations to improving the living conditions of the southern landless labourers (braceros), the Asturian miners and other sections of the industrial working class. However, in a shrinking economy, bankers, industrialists and landowners saw any attempts at reform in the areas of property, religion or national unity as an aggressive challenge to the existing balance of social and economic power. Moreover, the Catholic Church and the army were equally determined to oppose change. Yet the Socialists felt that they had to meet the expectations of those who had rejoiced at what they thought would be a new world. They also had another enemy – the anarchist movement.

The leadership of the anarchist movement expected little or nothing from the Republic, seeing it as merely another bourgeois state system, little better than the monarchy. At best, their trade union wing wanted to pursue its bitter rivalry with the Union General de Trabajadores, which they saw as a scab union because of its collaboration with the Primo de Rivera regime. They thirsted for revenge for the dictatorship’s suppression of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo throughout the 1920s. The hard-line activist wing of the anarchist movement, the Federación Anarquista Ibérica, aspired to greater liberty with which to propagate its revolutionary objectives. The situation could not have been more explosive. Mass unemployment was swollen by the unskilled construction workers left without work by the collapse of the ambitious public works projects of the dictatorship. The brief honeymoon period came to an end when CNT–FAI demonstrations on 1 May were repressed violently by the forces of order. It was the trigger for an anarchist declaration of war against the Republic and the beginning of a wave of strikes and minor insurrections over the next two years.36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Needless to say, anarchist activities against the Republic were eagerly portrayed by the right-wing media, and from church pulpits, as proof that the new regime was itself a fount of godless anarchy.37 (#litres_trial_promo) Despite these appalling difficulties, the Federación de Juventudes Socialistas shared the optimism of the Republican–Socialist coalition. When the Republic was proclaimed on 14 April, FJS militants had guarded buildings in Madrid associated with the right, including the royal palace. On 10 May, when churches were burned in response to monarchist agitation, the FJS also tried to protect them.38 (#litres_trial_promo) However, as the obstacles to progress mounted, frustration soon set in within the Socialist movement as a whole.

The first priority of the Socialist Ministers of Labour, Francisco Largo Caballero, and of Justice, Fernando de los Ríos, was to ameliorate the appalling situation in rural Spain. Rural unemployment had soared thanks to a drought during the winter of 1930–1 and thousands of emigrants were forced to return to Spain as the world depression affected the richer economies. De los Ríos established legal obstacles to prevent big landlords raising rents and evicting smallholders. Largo Caballero introduced four dramatic measures to protect landless labourers. The first of these was the so-called ‘decree of municipal boundaries’ which made it illegal for outside labour to be hired while there were local unemployed workers in a given municipality. It neutralized the landowners’ most potent weapon, the import of cheap blackleg labour to break strikes and depress wages. He also introduced arbitration committees (jurados mixtos) with union representation to adjudicate rural wages and working conditions which had previously been decided at the whim of the owners. Resented even more bitterly by the landlords was the introduction of the eight-hour day. Hitherto, the braceros had worked from sun-up to sun-down. Now, in theory at least, the owners would either have to pay overtime or else employ more men to do the same work. A decree of obligatory cultivation prevented the owners sabotaging these measures by taking their land out of operation to impose a lock-out. Although these measures were difficult to implement and were often sidestepped, together with the preparations being set in train for a sweeping law of agrarian reform, they infuriated the landowners, who claimed that the Republic was destroying agriculture.

While the powerful press and radio networks of the right presented the Republic as the fount of mob violence, political instruments were being developed to block the progressive project of the newly elected coalition. First into action were the so-called ‘catastrophists’ whose objective was to provoke the outright destruction of the new regime by violence. The three principal catastrophist organizations were the monarchist supporters of Alfonso XIII who would be the General Staff and the paymasters of the extreme right; the ultra-reactionary Traditionalist Communion or Carlists (so called in honour of a nineteenth-century pretender to the throne); and lastly a number of minuscule openly fascist groups, which eventually united between 1933 and 1934 under the leadership of the dictator’s son, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as Falange Española. Within hours of the Republic being declared, the ‘Alfonsine’ monarchists had met to create a journal to propagate the legitimacy of a rising against the Republic particularly within the army and to establish a political party merely as a front for meetings, fund-raising and conspiracy against the Republic. The journal Acción Española would peddle the idea that the Republican–Socialist coalition was the puppet of a sinister alliance of Jews, Freemasons and leftists. In the course of one month, its founders had collected substantial funds for a military coup. Their first effort would take place on 10 August 1932 and its failure would lead to a determination to ensure that the next attempt would be better financed and entirely successful.39 (#litres_trial_promo)

In contrast, the other principal right-wing response to the Republic was to be legal obstruction of its objectives. Believing that forms of government, republican or monarchical, were ‘accidental’ as opposed to fundamental and that only the social content of a regime mattered, they were prepared to work within the Republic. The mastermind of these ‘accidentalists’ was Ángel Herrera, head of the Asociación Católica Nacional de Propagandistas (ACNP), an elite Jesuit-influenced organization of about 500 prominent and talented Catholic rightists with influence in the press, the judiciary and the professions. They controlled the most modern press network in Spain whose flagship daily was El Debate. A clever and dynamic member of the ACNP, the lawyer José María Gil Robles, began the process of creating of a mass right-wing party. Initially called Acción Popular, its few elected deputies used every possible device to block reform in the parliament or Cortes. A huge propaganda campaign succeeded in persuading the conservative Catholic smallholding farmers of northern and central Spain that the Republic was a rabble-rousing instrument of Soviet communism determined to steal their lands and submit their wives and daughters to an orgy of obligatory free love. With their votes thereby assured, by 1933 the legalist right would be able to wrest political power back from the left.40 (#litres_trial_promo)

The efforts of Gil Robles in the Cortes to block reform and provoke the Socialists was witnessed, on behalf of El Socialista, by Santiago Carrillo, who had been promoted from the town-hall beat to the arduous task of the verbatim recording of parliamentary debates. This could be done only by dint of frantic scribbling. The job did, however, bring him into contact with the passionate feminist Margarita Nelken, who wrote the parliamentary commentary for El Socialista. Herself a keen follower of Largo Caballero at this time, she would encourage Santiago in his process of radicalization and indeed in his path towards Soviet communism.41 (#litres_trial_promo)

In the first months of the Republic, Santiago won his spurs as an orator, speaking at several meetings of the FJS around the province of Madrid. This culminated at a meeting in the temple of the PSOE, the Casa del Pueblo. Opening a bill that included the party president, Julián Besteiro, he was at first tongue-tied. However, he recovered his nerve and made a speech whose confident delivery contrasted with his baby-faced appearance. In it, he betrayed signs of the radicalism that would soon distinguish members of the FJS from their older comrades. He declared that the Socialists should not be held back by their Republican allies and that, in a recent assembly, the FJS had resolved that Spain should dispense with its army. His rise within the FJS was meteoric. He would become deeply frustrated as he closely followed the fate of Largo Caballero’s decrees and even liaised with strikers in villages where the legislation was being flouted. At the FJS’s Fourth Congress, held in February 1932 when he had just turned seventeen, he was elected minutes secretary of its largely Besteirista executive committee. This was rather puzzling since his adherence to the view of Largo Caballero about the importance of Socialist participation in government set him in opposition to the president of the FJS, José Castro, and its secretary general, Mariano Rojo.

Carrillo’s election was probably the result of two things – the fact that he was able to reflect the frustrations of many rank-and-file members and, of course, the known fact of his father’s links to Largo Caballero. Not long afterwards, he became editor of the FJS weekly newspaper, Renovación, which had considerable autonomy from the executive committee. From its pages he promoted an ever more radical line with a number of like-minded collaborators. The most senior were Carlos Hernández Zancajo, one of the leaders of the transport union, and Amaro del Rosal, president of the bankworkers’ union. Among the young ones was a group – Manuel Tagüeña, José Cazorla Maure, José Laín Entralgo, Segundo Serrano Poncela (his closest comrade at this time) and Federico Melchor (later a lifelong friend and collaborator) – all of whom would attain prominence in the Communist Party during the Civil War. Greatly influenced by their superficial and rather romantic understanding of the Russian revolution, they argued strongly for the PSOE to take more power. Their principal targets were Besteiro and his followers, who still advocated that the Socialists abstain from government and leave the bourgeoisie to make its democratic revolution.42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Carrillo’s intensifying, and at this stage foolhardy, radicalism saw him risk his life during General Sanjurjo’s attempted military coup of 10 August 1932. When the news reached Madrid that there was a rising in Seville, Carrillo – according to his memoirs – abandoned his position as the chronicler of the Cortes debates and joined a busload of Republican officers who had decided to go and combat the rebels. In this account of this youthful recklessness, he says that he left his duties spontaneously without seeking permission from the editor. However, El Socialista published a more plausible and less heroic version at the time. The paper reported that he had been sent to Seville as its correspondent and had actually gone there on the train carrying troops sent officially to repress the rising. Whatever the truth of his mission and its method of transport, by the time he reached Seville Sanjurjo and his fellow conspirators had already given up and fled to Portugal. The fact that Carrillo stayed on in Seville collecting material for four articles on the rising that were published in El Socialista suggests that he was there with his editor’s blessing.43 (#litres_trial_promo)