Полная версия:

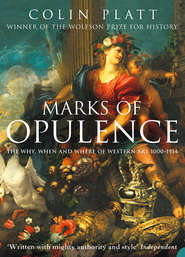

Marks of Opulence: The Why, When and Where of Western Art 1000–1914

MARKS OF OPULENCE

The Why, When and Where

of Western Art 1000–1900 AD

Colin Platt

Epigraph

With the greater part of rich people, the chief enjoyment of riches consists in the parade of riches, which in their eye is never so complete as when they appear to possess those decisive marks of opulence which nobody can possess but themselves.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), Book One, Chapter xi.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE A White Mantle of Churches

CHAPTER TWO Commercial Revolution

CHAPTER THREE Recession and Renaissance

CHAPTER FOUR Expectations Raised and Dashed

CHAPTER FIVE Religious Wars and Catholic Renewal

CHAPTER SIX Markets and Collectors

CHAPTER SEVEN Bernini’s Century

CHAPTER EIGHT Enlightened Absolutism

CHAPTER NINE Revolution

CHAPTER TEN The Gilded Age

Notes

Index

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features …

About the Author

Profile of Colin Platt

Life at a Glance

Top Ten Favourite Books

About the Book

A Critical Eye

The Bigger Picture

Read On

Have You Read?

If You Loved This, You’ll Like …

Find Out More

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

‘The simple truth’, wrote Philip Hamerton, ‘is that capital is the nurse and governess of the arts, not always a very wise or judicious nurse, but an exceedingly powerful one. And in the relation of money to art, the man who has money will rule the man who has art … (for) starving men are weak.’ (Thoughts about Art, 1873) Hamerton was a landscape-painter who had studied both in London and in Paris. However, it was chiefly as a critic and as the founding-editor of The Portfolio (1870–94) that he made his contribution to the arts. In 1873, Hamerton had lived through a quarter-century of economic growth: one of the most sustained booms ever recorded. He had seen huge fortunes made, and knew the power of money:

But [he warned] for capital to support the fine arts, it must be abundant – there must be superfluity. The senses will first be gratified to the full before the wants of the intellect awaken. Plenty of good meat and drink is the first desire of the young capitalist; then he must satisfy the ardours of the chase. One or two generations will be happy with these primitive enjoyments of eating and slaying; but a day will come when the descendant and heir of these will awake into life with larger wants. He will take to reading in a book, he will covet the possession of a picture; and unless there are plenty of such men as he in a country, there is but a poor chance there for the fine arts.1

In mid-Victorian Britain, it was Hamerton’s industrialist contemporaries – many of them the inheritors of successful family businesses – who were the earliest patrons of the Pre-Raphaelites. A generation later, it would be American railroad billionaires and their widows who created the market for French Impressionists. ‘You’ve got a wonderful house – and another in the country’, ran a recent double-spread advertisement in a consumer magazine. ‘You’ve got a beautiful car – and a luxury four-wheel-drive. You’ve got a gorgeous wife – and she says that she loves you. Isn’t it time to spoil yourself?’2 If one man’s trophy asset is a BeoVision Avant, another’s positional good is a Cézanne.

Positional goods are assets, like Cézannes, with a high scarcity value. They appeal especially to super-rich collectors, wanting the reassurance of ‘those decisive marks of opulence which nobody can possess but themselves’.3 But for the fine arts to prosper generally and for new works to be commissioned, the overall economy must be healthy: ‘there must [in Hamerton’s words] be superfluity’. ‘Accept the simplest explanation that fits all the facts at your disposal’ is the principle known as Occam’s Razor. And while economic growth has never been the only condition for investment in the arts, it is (and always has been) the most necessary. Collectors pay high prices when the market is rising; even the best painters need an income to continue. It was Sickert, the English Impressionist, who once told Whistler, ‘painting must be for me a profession and not a pastime’. And it was Sickert’s contemporary, Stanhope Forbes, who confessed to his mother, just before his fortunes changed: ‘The wish to do something that will sell seems to deprive me of all power over brushes and paints.’ Forbes’s marine masterpiece, A Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach (1885), painted in Newlyn the following year, at last brought him the recognition he had craved.

Before that happened, Forbes had depended on the support of well-off parents. And very few aspiring artists, even today, can succeed without an early helping hand. ‘Princes and writers’, wrote John Capgrave in 1440, ‘have always been mutually bound to each other by a special friendship … (for) writers are protected by the favour of princes and the memory of princes endures by the labour of writers.’ Capgrave (the scholar) wanted a pension from Duke Humphrey (the prince). So he put Humphrey the question: ‘Who today would have known of Lucilius [procurator of Sicily and other Roman provinces] if Seneca had not made him famous by his Letters?’ Equally, however, ‘those men of old, who adorned the whole body of philosophy by their studies, did not make progress without the encouragement of princes’. In Duke Humphrey’s day, ‘it is not the arts that are lacking, as someone says, but the honours given to the arts’. Accordingly, ‘Grant us a Pyrrhus and you will give us a Homer. Grant us a Pompey and you will give us a Tullius (Cicero). Grant us a Gaius (Maecenas) and Augustus and you will also give us a Virgil and a Flaccus (Horace).’4

There have been patrons of genius in every century: Abbot Desiderius in the eleventh century, St Bernard in the twelfth; Louis IX in the thirteenth century, Jean de Berri in the fourteenth; Philip the Good in the fifteenth century, Julius II in the sixteenth; and so on. Tiny seafaring Portugal has had three of them. Manuel the Fortunate (1495–1521), the first of those, could build what he liked out of the profits of West Africa and the Orient. Then, two centuries later, John V (1707–50) and Joseph I (1750–77) grew rich on the gold of Brazil. From the mid-1690s, word of the new discoveries in the Brazilian Highlands had spread quickly throughout Europe’s arts communities. And Western art can show few better examples of what biologists call ‘quorum-sensing’ than the instant colonizing of Joanine Portugal by foreign artists of all kinds – by the painters Quillard, Duprà and Femine, by the sculptors Giusti and Laprade, by the engravers Debrie and Massar de Rochefort, and by the architects Ludovice and Nasoni, Juvarra, Mardel and Robillon – most of whom returned home just as soon as the gold of Minas Gerais was exhausted.

Brazil’s ‘vast treasures’ included diamonds as well as gold, with sugar, hides, tobacco and mahogany. And the splendours of Portugal’s Rococo architecture under its Braganza kings owed as much to the fortunes of returned colonial merchants and administrators. In London a little later, Charles Burney, author of a four-volume General History of Music (1776–89), recognized the creative link between a thriving business community and the arts:

All the arts seem to have been the companions, if not the produce, of successful commerce; and they will, in general, be found to have pursued the same course … that is, like Commerce, they will be found, upon enquiry, to have appeared first in Italy; then in the Hanseatic towns; next in the [Burgundian] Netherlands; and by transplantation, during the sixteenth century, when commerce became general, to have grown, flourished, matured, and diffused their influence, in every part of Europe.5

London, when Burney wrote, had taken the place of Brussels and Amsterdam as the commercial capital of the West. And Burney’s artist-contemporaries, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, included Joshua Reynolds and George Romney, Thomas Gainsborough, George Stubbs and Benjamin West. When they were joined shortly afterwards by William Blake, John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, even the French had to acknowledge the excellence of British art – of Constable as a cloud-painter and of Turner as a colourist – indisputably of world class for the first time.

Commerce and peace go together. In Thomas Jefferson’s first inaugural address as President of the United States of America, he called for ‘Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations – entangling alliances with none.’ And in 1801, nobody knew better the profits of neutrality than Jefferson himself – planter, statesman and architect-connoisseur – presiding over the unprecedented growth of the republic’s economy when almost every other Western nation was at war. Erasmus had written movingly in 1517 of ‘the wickedness, savagery, and madness of waging war’, and had castigated princes ‘who are not ashamed to create widespread chaos simply in order to make some tiny little addition to the territories they rule’.6 Yet just two centuries later, ‘I have loved war too much’, confessed Louis XIV (1643–1715) on his deathbed. And during the Sun King’s long reign, even building – his other passion – had come second to campaigning; for the two main construction programmes at Louis’s enormous palace at Versailles – the first from 1668, the second ten years later – corresponded closely with rare intervals of peace. Charles XI of Sweden (1660–97), a contemporary of the French king, inherited an economy almost destroyed by war and by the military adventures of the Vasas. In the next generation, Sweden would be reduced to penury again as his son, Charles XII, took up arms. But for almost twenty years from 1680 (when Charles XI declared himself absolute) neutrality was the policy of his regime. During that time, Sweden’s treasury was replenished and its war-debts were cleared, leaving a sufficiency in Charles’s coffers to complete his country mansion at Schloss Drottningholm, near Stockholm, and to start another big Baroque palace in the capital.

‘Money’, wrote Bernard Shaw in The Irrational Knot (1905), ‘is indeed the most important thing in the world.’ And it is usually the very wealthy who control it. Yet there have been exceptional episodes in the history of Western art when the arts have been governed neither by princes nor connoisseurs, but by the ‘tyranny of little choices’ of the many. In recession-prone Europe, after the catastrophe of the Black Death (1347–9), few individuals were seriously wealthy. However, there has never been a time when more money has been spent on memorial and votive architecture than under the collective sponsorship of the gilds. After the Reformation, when the pains of Purgatory had been forgotten, it was the individual investment choices of men of modest means that supported the Dutch Golden Age. ‘All Dutchmen’, noted the English traveller Peter Mundy in 1640, fill their parlours ‘with costly pieces (pictures), butchers and bakers not much inferiour in their shoppes … yea many times black smithes, coblers, etc. will have some picture or other by their Forge and in their stall.’ There were more than two million new paintings on Dutch walls by 1660. ‘Their houses are full of them’, said John Evelyn.7

I end my book at the First World War, when many were asking what constituted art and what, in the last resort, it was for. ‘Is that all?’, asked the Modernist critic, Roger Fry, in his Essay in Aesthetics (1909), quoting a contemporary definition of the art of painting (‘by a certain painter, not without some reputation at the present day’) as ‘the art of imitating solid objects upon a flat surface by means of pigments’.8 Fry, of course, had much more to say. Yet he was writing at a time when ‘the visions of the cinematograph’ (Fry) and the ‘death of God’ (Nietzsche) had caused many of the old certainties to fade. The Fauvists in Paris and the Expressionists in Berlin were all reading Nietzsche at the beginning of the last century. They were as committed as the philosopher to new ways of seeing, but would probably have agreed also with his ‘sorrowful’ conclusion – reluctantly confessed in Human, All Too Human (1878) – that the arts would be the poorer without religion:

It is not without profound sorrow that one admits to oneself that in their highest flights the artists of all ages have raised to heavenly transfiguration precisely those conceptions which we now recognize as false: they are the glorifiers of the religious and philosophical errors of mankind, and they could not have been so without believing in the absolute truth of these errors. If belief in such truth declines in general … that species of art can never flourish again which, like the Divina commedia, the pictures of Raphael, the frescos of Michelangelo, the Gothic cathedrals, presupposes not only a cosmic but also a metaphysical significance in the objects of art.9

Almost the last of the religious artists in the grand classical tradition was the Parisian decorative painter, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (d. 1898). Puvis’s simple line and his non-naturalistic colours were strong influences on many Post-Impressionists. Yet, wrote Gauguin in 1901, ‘there is a wide world between Puvis and myself … He is a Greek while I am a savage, a wolf in the woods without a collar.’10 Twenty years earlier, Van Gogh had spoken similarly of the ‘savageries’ in his work: ‘so disquieting and irritating as to be a godsend to those (critics) who have fixed preconceived ideas about technique’.11 Maurice de Vlaminck, the one-time Fauvist wrote: ‘I try to paint with my heart and my loins, not bothering with style.’12 But necessary to modern artists though such primitivism had become, there was nothing naïve or unsophisticated about the avant-garde painters showing their work in London in 1912 at Roger Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition. ‘It is the work [wrote Fry] of highly civilized and modern men trying to find a pictorial language appropriate to the sensibilities of the modern outlook … They do not seek to imitate form but to create form; not to imitate life, but to find an equivalent for life … they aim not at illusion, but at reality.’13

Stimulated by rising prices, popular interest in the arts had never been higher than in the last decade before the Great War. ‘Art has become like caviar’, wrote the German critic, Julius Meier-Graefe, in 1904; ‘everyone wants to have it, whether they like it or not.’ However, ‘it is materially impossible [Meier-Graefe warned] to produce pure works of art at prices that will bring them within the means of the masses’.14 And a substitute had been found in the speculative commissioning of important new works – William Frith’s The Railway Station in 1862, or Holman Hunt’s The Shadow of Death eleven years later – for subsequent engraving and mass-sale. Frith had been uncertain about his subject until Louis Flatow, the dealer, took it up. ‘I don’t think’, Frith wrote in his Autobiography and Reminiscences (1890), ‘(that) the station at Paddington can be called picturesque, nor can the clothes of the ordinary traveller be said to offer much attraction to the painter – in short the difficulties of the subject were very great.’15 Yet such was his painting’s enduring appeal that engravings of The Railway Station were still hanging on parlour walls two generations later, when Clive Bell wrote:

Few pictures are better known or liked than Frith’s Paddington Station … But certain though it is that Frith’s masterpiece, or engravings of it, have provided thousands with half-hours of curious and fanciful pleasure, it is not less certain that no one has experienced before it one half-second of aesthetic rapture – and this although the picture contains several pretty passages of colour, and is by no means badly painted … Paddington Station is not a work of art; it is an interesting and amusing document … But, with the perfection of photographic processes and of the cinematograph, pictures of this sort are becoming otiose … (they) are grown superfluous; they merely waste the hours of able men who might be more profitably employed in works of a wider beneficence.16

Where Frith’s world ended and Bell’s began is debatable. In the 1890s, William Frith R.A. – ‘Chevalier of the Legion of Honour and of the Order of Leopold; Member of the Royal Academy of Belgium, and of the Academies of Stockholm, Vienna, and Antwerp’ – could still count on the support of the great majority of academicians in counselling aspiring artists to study ‘the great painters of old’, while predicting that ‘the bizarre, French, “impressionist” style of painting recently imported into this country will do incalculable damage to the modern school of English art.’17 However, when the once-fashionable Berlin Realist, Anton von Werner (1843–1915), looked back in 1913 on his long career, all he could see was waste and failure: his careful art overtaken by the daubs of the Expressionists.18 Some believe Gustave Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans (1850) to be the first ‘modern’ work; others see Manet’s Olympia and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (both of 1863) to be Modernism’s beginning; and there are those again who would prefer to start only with the Cubists. However, what is certain is that the ‘incessant work’ of a Werner or a Frith – ‘The whole of the year 1861, with fewer interruptions than usual, was spent on The Railway Station’, Frith noted in his journal19 – was no longer demanded of the successful modern artist; and money, as a consequence, had lost its power. There is only one nation today – the United States of America – where art convincingly follows money, and where ‘superfluity’ still makes everything possible. Take, for example, the extraordinary architecture of present-day Chicago. ‘Recognisableness’, wrote Aldous Huxley in Art and the Obvious (1931), ‘is an artistic quality which most people find profoundly thrilling.’ And sixty years afterwards, Hammond, Beeby and Babka, architects of the Washington Library Center (1991), were to give Chicago’s literati a cornucopia of such references: from the Library’s rusticated base, through its rundbogenstil façade, to the huge grenade-like exploding terminals of the pediment.20

The Grand Projet still lives on in modern architecture. And there are more big country houses being built in Britain today than at any time since the mid-nineteenth century. At Mexico’s Guadalajara, Jorge Vergara, a self-made billionaire, has hired the world’s most famous architects, including the Deconstructivists Philip Johnson and Daniel Libeskind, to build him a showcase of their works. In Seattle, Bill Gates’s huge new mansion is set to become the largest private palace of his 1990s generation: the nearest equivalent, a century on, of George W. Vanderbilt’s Biltmore House (1888–95) – prodigal emblem of America’s Gilded Age. But as national economies continue to grow, the pre-eminence of the individual patron has been lost. John Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), second-generation banker and art-collector extraordinary, was wealthier than any of the Vanderbilts. He began serious collecting only in the 1890s, yet was able to amass, before his death, a remarkable hoard of paintings and drawings, manuscripts and incunabula, ivories and enamels, tapestries, maiolica and oriental porcelains, second to none in the West. The like would be impossible today. In 1913, J.P. Morgan’s personal fortune, it has been estimated, could have met the entire investment needs of the United States of America for as much as a third of that year. To do the same now would require the combined fortunes of the top sixty super-rich, with Bill Gates (‘the world’s richest billionaire by a wide margin’) accounting for barely a fortnight.21

For better or worse, the individual collector-patron has lost the power to transform an entire culture. We are unlikely, that is, ever to see again another Peter or a Catherine ‘the Great’. But the arts too have changed radically since the birth of Modernism. And if I end my ‘essay’ – the word is Jacob Burckhardt’s – with the Fall of the Old Empires and the Academies’ dying breath, it is because nothing thereafter has been the same. An essay, I warned my students, must have an argument. And I return repeatedly in this book to money as the driver of high achievement in the arts, and to the transforming power of great riches. However, I have never seen money as the sole begetter of high quality, any more than Burckhardt himself thought the ‘genius of the Italian people’ (Italienischer Volksgeist) the only explanation of the Renaissance. ‘In the wide ocean upon which we venture’, Burckhardt began The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), ‘the possible ways and directions are many; and the same studies which have served for this work might easily, in other hands, not only receive a wholly different treatment and application, but lead also to essentially different conclusions.’22 I take his point entirely; for one very good reason why Burckhardt’s Civilization has become a classic and is still read today, is the candour of that disavowal of omniscience.

My final paragraph is an apology. In the course of my argument, I have given many important artists too little space or, in some cases, have failed to mention them at all. One missing person is the Copenhagen painter, Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916), master of the psychologically-penetrating portrait and quiet interior. Like the Unknown Warrior, he shall stand for all the rest: in memoriam.

CHAPTER ONE A White Mantle of Churches

Rodulfus Glaber (c. 980–c. 1046), chronicler of the Millennium and author of The Five Books of the Histories, witnessed two millennial years in his lifetime. The first was the Millennium of the Incarnation of Christ (1000); the second, the Millennium of his Passion (1033). While disposed to tell of miracles and portents, of plagues, of famines and other horrors, Glaber’s message in neither case was of Apocalypse. Instead he chose to write not of the Coming of Antichrist nor of a Day of Wrath, but of a Church resurgent and victorious:

Just before the third year after the millennium [Glaber writes of 1003], throughout the whole world, but most especially in Italy and Gaul, men began to reconstruct churches … It was as if the whole world were shaking itself free, shrugging off the burden of the past, and cladding itself everywhere in a white mantle of churches.1

Cathedrals, monasteries, and even ‘little village chapels’, Glaber continues, ‘were rebuilt better than before by the faithful’. And of this, as an untypically restless monk who never stayed long in one place, Glaber had considerable experience. He was at Saint-Bénigne at Dijon when, in 1016, Abbot William (990–1031) consecrated the new church he had rebuilt ‘to an admirable plan, much wider and longer than before’. And it was to Cluny’s Abbot Odilo (994–1048), whose famous boast it was (echoing Caesar’s) that he ‘had found Cluny wood and was leaving it marble’, that Glaber came to dedicate his Histories.