Полная версия:

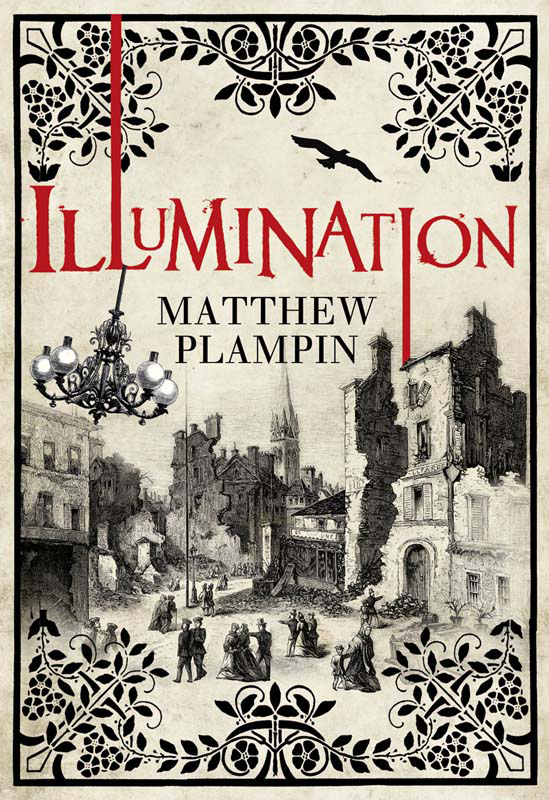

Illumination

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

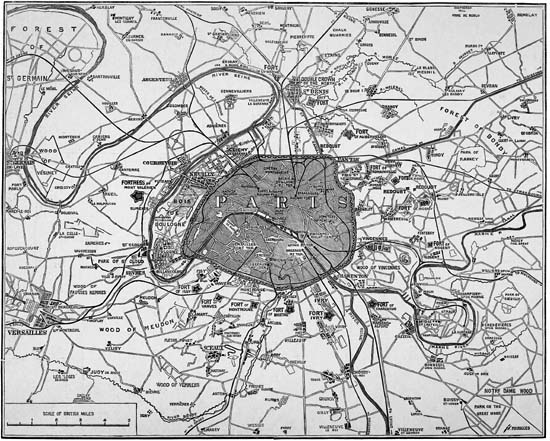

Map

Epigraph

Prologue: Venus Verticordia – London 1868

Part One: City of Light – Paris, September 1870

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Part Two: The Goddess of Revolt

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Part Three: Wolf Steak at the Paris Grand

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Part Four: Illumination

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Author’s Note

About the Author

Also by Matthew Plampin

Copyright

About the Publisher

For my mother

I no longer remember what Bakunin said, and it would in any case scarcely be possible to reproduce it. His speech was elemental and incandescent – a raging storm with lightning flashes and thunderclaps, and a roaring of lions. The man was a born speaker made for the revolution. If he had asked his hearers to cut each other’s throats, they would have cheerfully obeyed him.

The Memoirs of Baron N. Wrangel

It is not enough to conquer; one must also know how t o seduce.

Voltaire

Hannah entered the drawing room and froze: what appeared to be a miniature kangaroo had climbed up onto a chair and was nibbling at a vase of lilies. She stared at it for a few seconds – the black lips pulling delicately at the petals, the elongated toes rubbing mud into the satin upholstery – and wondered what she should do. Creatures both strange and familiar were everywhere at Tudor House. Caged parakeets shrieked in the hall; racoons and marmots scuttled beneath the furniture, their claws tapping on the floor tiles; and at dinner, a huge, sad-eyed dog (an Irish deerhound, they were told) had loped in and laid itself by the hearth without even glancing at the assembled guests.

‘My apologies, Miss Pardy,’ said her host, who had arrived at her side, ‘the little buggers are always escaping from their pen and finding their way indoors. There is nought so bold, so precious clever, as a greedy wallaby. Do excuse me – excuse us.’

He edged forward with his arms outstretched, repeating the beast’s name (which was Freda) in the tone of a doting father. The wallaby slipped from the chair, bounding sharply to the right and then to the left – a technique developed to foil the predators of the Australian desert that proved more than a match for a rotund painter-poet in a Chelsea drawing room.

The other guests had started to drift in. Instead of helping their host they gathered like spectators around a street show, cheering as Freda dodged another lunge. Most of them were writers or artists, or those who live off writers or artists; before long they were spouting poetry again, something about a knight’s quest this time, bellowing the verse in good-humoured competition. Hannah didn’t recognise it. She scratched her elbow through the sleeve of her gown. The evening was not going to plan.

Freda made it to the French doors, one of which had been left ajar, and hopped out into the cool April evening. Her owner was close behind, followed in turn by eight or nine chortling gentlemen. Among them was Clement, lighting a cigarette whilst recounting a joke he’d heard in an alehouse. He was doing rather better with these people than Hannah, despite knowing as much about art as the butcher’s boy. Opposite twins, that was Elizabeth’s favoured description: siblings born together who were different in every possible regard. This phrase had always made Hannah wince, but she could not deny the truth in it. Her brother had an easy amiability that she would never possess. Clem could bob along quite happily on the surface of almost any society – whilst she sank down into its depths, growing restless and irritable, longing to be away.

A finger prodded Hannah’s hip. Elizabeth was smiling, but her eyes were hard with purpose. She nodded after their host. ‘Follow him.’

‘He is not interested, Elizabeth. Not in the least.’

‘What rot. He’ll soon be finished with that ridiculous pet of his and then you must act. This opportunity may not be repeated.’

‘It is futile. You were at the table. You heard their conversation.’

‘They are unconventional. I warned you of this, Hannah. They are artists. They think differently, even by our standards.’

Hannah sighed. ‘They talked of money and their love affairs – gossip, Elizabeth – and recited a great long bookshelf’s worth of poetry at one another. What is so unconventional about that?’

Elizabeth’s smile vanished. It pleased her to think that these friends of hers were outrageous, an affront to propriety, and she did not appreciate Hannah suggesting otherwise. ‘Perhaps, then, you should have done something to make yourself worthy of their notice. But once more you insist upon surly silence, coupled with a scowl that spoils you completely. How much do you suppose that will achieve, you impossible girl?’

Hannah would not be scolded. ‘And what exactly was I to say? Their only care was the extent of my resemblance to you. None of them so much as mentioned my work. You said that they were curious – that you’d prepared the ground.’

This was a significant understatement. Back in St John’s Wood, Elizabeth had declared that the evening would be nothing less than an initiation, launching Hannah into a vibrant world rich with possibilities. An alliance with the Cheyne Walk circle could lead to contacts, to sales, to an arrangement with a picture dealer – to an artistic career. Hannah had actually been excited, despite everything she knew about Elizabeth’s promises and predictions; this, at last, had seemed like a real chance. Within a half-hour of their arrival at Tudor House, however, all hope had been dispelled. There was nothing for her here. Elizabeth had done it again, and Hannah had cursed herself for relaxing her usual scepticism.

‘You must show some blessed backbone,’ Elizabeth said. ‘You have the matter in reverse. You are allowing him to overlook you.’

Hannah frowned at the floor. An oriental rug was laid across it, stained and faded by the passage of dirty paws. She decided to stay quiet.

Elizabeth pointed to a spot beside the grand piano. ‘Stand there,’ she instructed, starting for the garden. ‘I will follow him.’

The last of the party came in from the dining room – three young women, the only other females present that evening. All were unaccompanied, but this drew no notice at Tudor House. They’d been seated at the far end of the dinner table from Hannah; they hadn’t been introduced, and had said and eaten very little. The three of them were oddly alike, pale and slender with their auburn hair worn down, clad in loose dresses so white they appeared to glow softly in the gaslight. Hannah wasn’t easily intimidated, yet couldn’t help re-evaluating her own garment; what at home had been a subtle celestial grey now seemed as drab as a day-old puddle.

The three women fell among the cushions of a long sofa, settling into each other’s arms. This casual grace was undercut by their twanging accents, those of ordinary Londoners, which placed them some distance beneath the artistic gentlemen out whooping in the garden. Was this a harem, kept in a similar manner to the painter-poet’s private zoo? Hannah didn’t suppose that such an arrangement was beyond these people. One of the women was looking over at her, she realised, making an assessment then whispering to her friends; they leaned in, heads touching, to share a wicked giggle. Hannah turned away abruptly, searching the drawing room for a distraction. This wasn’t difficult. Every surface was crowded with statuettes and vases, unidentifiable musical instruments or items of exotic jewellery – a collection as vast as it was haphazard. She went to a cluster of jade figurines on a sideboard, suddenly fascinated.

There was laughter in the garden, and Elizabeth reappeared through the French doors with the painter-poet. The taller by two clear inches, she was leading him along as if escorting a convalescent. He was fretting about Freda, who remained at large; she was offering reassurance, telling him that his walls were high and his gardener well practised in dealing with escapees. They drew to a halt a few feet before Hannah.

‘And here she is, Gabriel,’ Elizabeth announced, ‘the reason I ventured out among the menfolk to claim you: my Hannah. Is she not a dove? A skylark, like that of dear Shelley: a star of heaven in the broad day-light?’

Hannah managed a feeble smile; she thought this a peculiar way to broach the subject of her paintings. Their host remained distracted, his small, sunken eyes twitching between the room’s various doorways. He looked as if he was prey to many maladies, of both mind and body – a man locked into an inexorable decline. The three women on the sofa were waving, trying to coax him over, but he paid them no notice.

‘Oh I agree, madam, a skylark, yes,’ he answered, running a hand through his thinning hair. ‘I’m afraid you must excuse me, though. Another crucial matter requires my attention – one quite unrelated to wallabies. It’s my blockheaded errand boy, you see. I have given him instructions, very specific instructions, but the clod is so extraordinarily slow that I cannot tell if he—’

‘People have claimed,’ Elizabeth continued, ‘that she is the picture of me when I was her age; a duplicate, if you like. My feeling, however, if I am quite honest, is that she has a quality I did not. A Renaissance quality. A note of Florence, perhaps, in the late Cinquecento; the beautiful purity one sees in the maidens of Ghirlandaio. It must come from Augustus’s side.’

Mention of Hannah’s father, dead a decade now, was designed to pin their host in place. Augustus Pardy had been a poet of renown, author of the ‘Ode to Dusk’, the verse-play Ariadne at Minos and a number of other commended pieces. He was held in some esteem at Tudor House; Hannah suspected that it was largely for his sake that Elizabeth continued to be invited to these dinners. She held her own, naturally, with endless tales of her foreign travels and the celebrity they had once brought, but her late husband’s name still served as her foundation.

The painter-poet, for the moment at least, was snagged. ‘Your husband was certainly a striking fellow,’ he murmured.

‘She fits so very well among these treasures, does she not? Why, it is like she belongs here, in this enchanting haven of yours.’ Elizabeth brought them closer. ‘And she has a question for you, Gabriel. About your art.’

Hannah attempted to hide both her surprise and the utter blankness that followed it. Seconds passed, piling up; their host cleared his throat; Elizabeth’s expectant gaze glared against her.

‘I do envy your position here beside the river,’ she said eventually. ‘I am sure that if I lived at Tudor House I would be out on the embankment with my easel every morning. Might I ask how often you avail yourself of its sights?’

This made him laugh. ‘Heavens above, I could never work outside! I trade in beauty, Miss Pardy, not coal-smoke and low-hanging cloud! What could there possibly be for my brush out on the Thames? And there are the flies, you know, and the dust, and all the blessed people … It’s a French idea really, this outdoor painting, and results only in the most beastly slop.’ He fixed Hannah with a quizzical expression. ‘But I believe you mentioned an easel, miss. Do you paint?’

There was another brief silence.

Hannah looked back to the jade figurines. She imagined herself smashing them one by one in the fireplace. ‘Our host,’ she stated, ‘is asking if I paint.’

Elizabeth ignored her. ‘You can see something there though, Gabriel, can’t you? As we discussed in the Garrick?’ Her voice was brisk; she was attempting to close a deal. She nodded towards the women on the sofa. ‘Her colouring is lighter than that of Miss Wilding and these others, but then variety is so often the key to success. Perhaps a blonde would—’

‘See something?’ Hannah interrupted. ‘Elizabeth, what on earth are you—’

The painter-poet was growing uncomfortable. ‘Now look here, Bess,’ he said, tugging at his neat little beard, ‘I have told you that I don’t want it. I don’t want the bother or the notice it will bring. I have decided upon my course and will not waste time with second thoughts.’

‘What is he talking about?’ Hannah demanded – although a couple of good guesses were forming in her mind. ‘What doesn’t he want?’

As always, Elizabeth refused to acknowledge defeat. ‘For goodness’ sake, Gabriel, you must not be so damnably stuck in your ways. Hannah may not be quite your normal type but without change, without development, we become stagnant, do we not? Such a painting would serve as the ideal culmination for my account of your career. It would bind author and subject, don’t you see, in a most compelling manner. Interest is sure to be enormous. I predict a serialisation – in the Athenaeum at the very least – and a volume on the stands by the end of the year. Come now, don’t be such a confounded mule. Give your consent and I can promise—’

Tudor House’s errand boy, a gangling youth in cap and braces, filled the doorway that led out to the hall, torn between hailing his master and gaping at the women on the sofa. Provided with the excuse he needed to escape them, their host backed away, reeling off an apology before snapping a reprimand at his boy. Elizabeth watched him go; there was nothing she could do. She shook a crease from her lilac dress, taking care not to meet her daughter’s eye.

‘Explain this,’ Hannah said. ‘Now.’

Elizabeth was unrepentant. ‘If you cannot grasp it for yourself, Hannah, then I have truly failed.’

The artistic gentlemen were filing in from the garden. A spotless mahogany easel was carried through and erected by the piano; the painter-poet fiddled nervously with the gas fittings, opening valves to illuminate the room as much as possible; and finally, at his signal, the canvas was brought before them.

Hannah had never seen an example of their host’s work. She knew about his central role in the Pre-Raphaelite controversy, of course, but that was two decades old; and furthermore, the major paintings it had produced all seemed to be by other hands. He’d become a mysterious figure, enjoying reputation without scrutiny, believed to be selling his startling canvases to a network of buyers across the British Isles yet shunning any form of public exhibition or exposure. Accordingly, although determined to extract a confession from Elizabeth, Hannah could not resist glancing over.

Unframed, unvarnished even, the painting had come straight from the studio upstairs. It depicted the head and shoulders of a young woman, roughly life-sized and quite naked. Her skin was flawless, suffused with warmth, free from the faintest wrinkle or blemish. Flowers crowded around her, the colours unearthly in their richness – honeysuckle blooms rendered in curls of burning orange, roses that ranged from blushing cerise to the ruby blackness of blood. This woman’s beauty had been refined somewhat, but Hannah recognised her immediately. The wide-set green eyes, the slightly heavy jaw, the red, pouting mouth: it was the girl from the sofa, Miss Wilding, who’d mocked her a minute earlier. Indeed, with the unveiling of the picture its model had shifted to the front of her cushion and was preening like an actress at her curtain-call. A cold thought struck through Hannah: that is what my mother had planned for me.

This was no straightforward portrait, however. Allegorical items were jammed into every corner. Behind the woman hung a gold-leaf halo, fringed unaccountably with buttery moths; off to the right was a bluebird, spreading its wings for flight. In one slender hand she held the apple of temptation, of original sin, and in the other Cupid’s arrow, angled so that it pointed directly at her left nipple – this was Eve and Venus combined, a fleshy goddess neither pagan nor Christian.

To Hannah the result was absurd, overripe and weirdly lifeless, but the artistic gentlemen could scarcely contain their delight. Flushed with wine, they proclaimed the composition to be masterful in its simplicity, the brushwork consummate, and the overall effect so intoxicating that it almost brought one to a swoon. Miss Wilding was showered with compliments and joking avowals of love, and told that she had been captured precisely.

‘The title is Venus Verticordia,’ announced the painter-poet with a flourish, bolstered by his friends’ flattery, ‘the heart-turner, the embodiment of desire – the divine essence of female beauty.’

‘And that she is!’ exclaimed a notable novelist, moving in for a detailed inspection. ‘Dear God, Gabriel, that she dashed well is!’

Hannah resolved to leave. She walked away from the sideboard and cut through the middle of the company. Clement said her name; others laughed and swapped remarks, assuming that her exit was provoked by a fit of feminine jealousy. She didn’t care. Let these idiots think what they pleased. She wanted only to be gone.

Elizabeth caught her on the chequered tiles of the hall. ‘Go no further, Hannah. We are not finished here.’

‘No, Elizabeth,’ Hannah replied, remaining steady, ‘we most certainly are.’

‘The Venus has upset you.’ Elizabeth was perfectly calm. Hannah’s stormings-out didn’t offend her; she would usually applaud them, in fact, as evidence of her daughter’s fighting spirit. ‘It is a crude specimen, I grant you, but you must see that if you were to sit for Gabriel the two of you would be alone for many hours. There would be ample time for you to explain your ideas and win his support.’

This was too much; Hannah’s composure deserted her. ‘Skylarks!’ she spat. ‘Ghirlandaio! You were trying to sell me. Is that where we stand, Elizabeth? Am I merely an object for you to bargain with?’

Elizabeth looked towards the front door; her profile, once featured on the cover plate of a dozen bestselling volumes and still formidably handsome, was outlined against the deep crimson wallpaper. ‘I am disappointed that you choose to take such a naïve view.’

‘What in blazes is naïve about it? Your plan was to deliver me to this Chelsea hermit of yours – to have him fashion me into a bare-breasted fancy for some banker to pant over in his study – so that he’d permit you to write a book about him and breathe life back into your wretched career!’

Hannah was shouting now. Parakeets flapped and squawked in their cages; a stripe-tailed mammal scurried into a rear parlour. All conversation in the drawing room had ceased somewhere around ‘bare-breasted fancy’. Gentlemen’s shoes thudded across the faded rug; they were acquiring an audience. Aware that their host would be in it, and had probably heard her daughter’s pronouncements, Elizabeth rose to his defence.

‘The Venus may not be to your taste, Hannah – and you are, let us be honest here, very particular – but you must surely appreciate the thinking behind it. Beauty, that is Gabriel’s creed: the creation of an art that is independent from religion, from morality, from every conventional form. An art that exists only for itself.’

‘An art, you mean, that has been entirely severed from reality – that exists only in a perverse, febrile dream! At least the French painters he so disdains engage with life, with what is around them, whereas that daub in there – it’s like this damned house. It is a retreat from the world, an evasion, a refusal to—’

A loud snort of amusement from the drawing room knocked Hannah off her stride. Elizabeth seized the chance to retaliate, asking what her daughter would have instead – pictures of pot-houses and rookeries, of dead dogs in gutters? – but Hannah found that her will to argue had been extinguished, shaken out like a match.

‘You lied to me,’ she said bluntly. ‘You told him nothing about my painting. You brought me here only to serve your own ends.’

Elizabeth came nearer, lowering her voice. ‘Oh, spare me that injured tone! It was a harmless manipulation that might ultimately have yielded results for us both. You must not be so damnably sensitive, Hannah.’ Her manner softened very slightly. ‘There is hope yet, I believe, if we work in concert. Something can always be salvaged.’

Hannah almost laughed; she took a backward step, then two more. Elizabeth’s grey eyes had grown conspiratorial, inviting her daughter to join with her as an accomplice – a standard strategy of hers when things went sour. Hannah would not accept.

The front door was weighty, and its hinges well oiled; the slam reverberated through the soles of Hannah’s evening shoes as she ran down the painter-poet’s path. Elizabeth had insisted she wear her hair up, to show off the line of her neck. The real reason for this was now obvious; once out on Cheyne Walk she took an angry satisfaction in pulling it loose, the pins scattering like pine needles on the pavement as the ash-blonde coil unravelled across her back. The night was turning cold. Ahead, past the road, a barge chugged along the black river, its bell ringing. Hannah paused beneath a street lamp and considered the walk home: seven miles, eight perhaps, through several unsavoury districts. It was the only bearable option.

Before she could start, Clement emerged from Tudor House. She watched her twin approach, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, moving from the gloom into the yellow light of her street lamp. His costume bordered on the comical. The formal suit he wore was several years old and cut for a rather more boyish frame; the necktie was escaping from his collar and threatening to undo itself altogether. It invariably fell to Clement to serve as the Pardy family’s mediator, a role that fitted him little better than his suit; he was an awkward peacemaker, prone to vagueness and the odd contradiction, but there was simply no one else to do it. His grin, intended to mollify, looked distinctly sheepish.

‘The woman is a monster,’ he began. ‘It cannot be denied.’

Hannah wasn’t taken in. The aftermath of her ructions with Elizabeth followed a well-established pattern. She crossed her arms and waited.

‘I do think she’s embarrassed, though. These people really appear to mean something to her.’

‘They are ludicrous. A gang of reptiles.’

Her brother, unfailingly decent, could not let this pass. ‘I say, Han, that’s hardly fair. A couple of them are pretty remarkable, in their way. There was this one little chap with the most gigantic head, a poet he said he was, who claimed to have—’

‘I suppose she is apologising for me?’ Hannah broke in. ‘Begging our host’s forgiveness?’

Clement tossed away his cigarette. ‘Actually, when I left she was laughing it off – telling them that she had no idea that her daughter had grown so conventional, and asking for suggestions as to how it might be corrected.’