Полная версия:

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

THE QUEEN

Elizabeth II

and the Monarchy

Diamond Jubilee Edition

BEN PIMLOTT

Dedication

To my family

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

LIST OF PLATES

CARTOONS

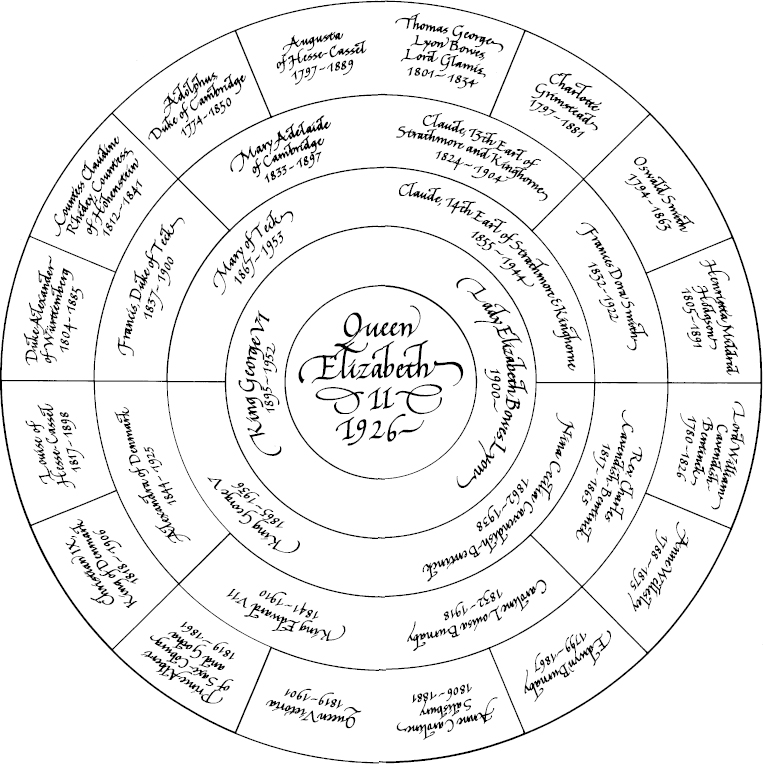

QUEEN ELIZABETH II 1926

FOREWORD - TO THE DIAMOND JUBILEE EDITION

FOREWORD - TO THE GOLDEN JUBILEE EDITION

PREFACE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

AFTERWORD - JEAN SEATON

NOTES

SOURCES AND SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

About the Author

Praise for The Queen

Copyright

About the Publisher

LIST OF PLATES

Princess Elizabeth on a tricycle, 1931 (Hulton Archive)

Earl and Countess of Strathmore, September 1931 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth with George V and Queen Mary at Bognor, 1929 (The Royal Archives © 2001 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

145 Piccadilly (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth in the Quadrangle at Windsor Castle watching a military parade and saluting the Commanding Officer, May 1929 (The Royal Archives © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Duke and Duchess of York, George V, Queen Mary, Princess Elizabeth and Alla at Balmoral, 1927 (Hulton Archive)

Edward VIII, Princess Elizabeth, Princess Margaret and the Duke of York at Balmoral, 1933 (Popperfoto)

Princess Elizabeth, Princess Margaret and ‘Crawfie’ leaving the YMCA, May 1939 (Hulton Archive)

George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret at Abergeldie, August 1939 (The Royal Archives © 2001 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

The Coronation of George VI, 1937 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth and Philip at Dartmouth, July 1939 (Sir William Peek)

Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret driving a pony and trap, August 1940 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth as a member of the ATS, April 1945 (Hulton Archive)

George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Princess Elizabeth, Princess Margaret and Sir Winston Churchill on VE-Day 1945 (Hulton Archive)

Prince Philip and Princess Elizabeth at the wedding of Lord Brabourne and Patricia Mountbatten at Romsey, 1946 (Topham)

Princess Elizabeth during a deck game on HMS Vanguard, April 1947 (Popperfoto)

Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret riding on the seashore in South Africa, 1947 (The Royal Archives © 2001 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip on their wedding day, November 1947 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth arriving at Westminster Abbey with her father for her marriage to Prince Philip, November 1947 (Hulton Archive)

Prince Charles with Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, July 1949 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth and the Queen at Hurst Park Races, January 1952 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth with Mountbatten at a ball at the Savoy, 3rd July 1951 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen arriving at Clarence House after her father’s death, 7th February 1952 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen as she drives to Westminster for the State Opening of Parliament, 1952 (Hulton Archive)

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II showing the Queen wearing her crown and preparing to receive homage, 2nd June 1953 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen Mother with Prince Charles at the Coronation, 2nd June 1953 (Hulton Archive)

Queen Elizabeth holding a model zebra with Princess Elizabeth, Peter Townsend and Princess Margaret in South Africa, 1947 (Popperfoto)

The Queen, and the Duke of Edinburgh with Sir Anthony and Lady Eden, 25th July 1955 (Popperfoto)

Daily Mirror front page ‘Smack! Lord A. gets his face slapped,’ 7th August 1957 (By permission of the British Library/Mirror Syndication)

Sir Michael Adeane (Godfrey Argent for the Archives of the National Portrait Gallery/Camera Press London)

The Queen with various members of the Government including Harold Macmillan, 16th February 1957 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen with Charles de Gaulle at Covent Garden, April 1960 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen with her corgis, 8th February 1968 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen on Britannia, 1972 (Patrick Lichfield/Camera Press London)

The Queen with Princess Anne, 1965 (Camera Press London)

The Investiture of the Prince of Wales, 1st July 1969 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen with Lord Porchester, 1966 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen at Aberfan, 29th October 1966 (Hulton Archive)

A student drinks from a bottle in front of the Queen at Stirling University, 12th October 1972 (© Scotsman Publications)

The Queen with Sir Martin Charteris on board Britannia, 31st October 1972 (Patrick Lichfield/Camera Press London)

The Queen on a Jubilee walkabout, 20th June 1977 (Ian Berry/Magnum Photos)

The Queen, Prince Philip and Prince Charles in Australia, 1970: ‘as short as we dared’ (by permission of Sir Hardy Amies)

The Queen with Harold Wilson, 24th March 1976 (Hulton Archive)

Prince Andrew returns from the Falklands, 1982 (Bryn Colton/Camera Press London)

The Queen with Margaret Thatcher and Hastings Banda, 3rd August 1979 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth with President Truman, 4th November 1951 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen with Prince Philip and the Kennedys, 6th June 1961 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen with President Carter and Prince Philip, 10th May 1977 (Hulton Archive)

The Queen riding with President Reagan in Windsor Great Park, 1982 (Tim Graham)

The Queen and Prince Philip with the Clintons, 29th November 1995 (Tim Graham)

The Queen with a fireman at Windsor Castle, 21st November 1992 (Hulton Archive)

‘HM The Queen’ by Antony Williams 1995 (Mall Galleries)

Detail from a painting by Michael Noakes. Study for a group portrait commissioned by the Corporation of London 1972.(Reproduced by kind permission of HRH The Prince of Wales)

Princess Elizabeth seen through syringa, 8th July 1941 (Hulton Archive)

Princess Elizabeth and her mother at the Derby, 4th June 1948 (Hulton Archive)

Richard Nixon is filmed shaking Prince Charles’s hand for the Royal Family film (BBC © Crown)

The Queen visits the Children’s Palace, Canton, October 1986 (Tim Graham)

It’s a Royal Knockout! June 1987 (Photographers International Picture Library)

The Queen and the Princess of Wales with bridesmaids, 1981 (Patrick Lichfield/Camera Press London)

The Princess of Wales in New York 1995 (Tim Graham)

Welcome the Queen (British Pathe plc/National Portrait Gallery, London)

Andy Warhol painting of the Queen (Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom 1985 by Andy Warhol © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, NY and DACS, London 2002)

Sticker artwork for single ‘God Save The Queen’, 1977 by Jamie Reid

The Queen as depicted by Spitting Image, 1985 (Spitting Image Productions)

Detail of Trooping the Colour by William Roberts (© Tate London 2001)

Queen Anne touching Dr Johnson, when a boy, to cure him of Scrofula or ‘King’s Evil’ (Private Collection/Bridgeman Art Library)

The Princess of Wales meets a resident of the Lord Gage Centre, Newham, East London, September 1990 (Tim Graham)

‘The Apotheosis of Princess Charlotte’, oil painting by Henry Howard, 1818 (National Trust Photographic Library)

The sea of flowers and bouquets outside Kensington Palace after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, September 1997 (Justin G. Thomas/Camera Press)

The Funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, September 1997 (Mark Stewart/ Camera Press)

Mourners in Hyde Park during the funeral service of Diana, Princess of Wales, September 1997 (© Chris Steele-Perkins/Magnum Photos)

The Queen leaving HMY Britannia for the last time, 11 December 1997 (Tim Graham)

The Queen and Donald Dewar after the Scottish Parliament was officially opened in Edinburgh, 1 July 1999 (Roger Donovan/PA Photos)

The Queen joined Mrs Susan McCarron (front left), her son James and Liz McGinniss for tea in their home in the Castlemilk area of Glasgow, 7 July 1999 (Dave Cheskin/PA Photos)

The Queen gives Maundy Money to 150 Christian pensioners at Westminster Abbey, 12 April 2001 (Camera Press)

The Queen picks up a shot pheasant and rings its neck while out on a shoot on the Sandringham Estate, 18 November 2000 (Alban Donohoe Picture Service)

‘The Queen and I’ by Sue Townsend, March 1994 (Donald Cooper/ Photostage)

Camilla Parker-Bowles at Somerset House in London for a party hosted by the Press Complaints Commission, 7 February 2001 (Tim Graham)

The Queen and Pope John Paul II exchanging gifts in his private office in the Vatican City in Rome, 17 October 2000 (Tim Graham)

The Moon Against the Monarchy protest, 3 June 2000 (Stefan Rousseau/ PA Photos)

The State Opening of Parliament, 20 June 2001 (Tim Graham)

Prince William during his Raleigh International expedition in southern Chile, 11 December 2000 (Tim Graham Picture Library)

The Queen visits Kingsbury High School in Brent to launch the Royal web site, 6 July 1997 (Tim Graham Picture Library)

CARTOONS

The Flowers and the Princesses (Reproduced by permission of Punch. Published on 28th April 1937)

Birthday Greetings (Reproduced by permission of Punch. Published 23rd April 1947)

Vicky on the Altrincham affair (Mirror Syndication/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Daily Mirror 14th August 1957)

Jak ‘Your Move!’ (Atlantic/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Evening Standard 5th March 1968)

Steadman ‘Up the Mall’ (Ralph Steadman. Published in Private Eye 4th July 1969)

Rigby ‘And Treble time . . .’ (News International Newspapers Ltd./Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sun, 3rd December 1971)

Franklin ‘Singing in the Reign’ (News International Newspapers Ltd./John Frost Historical Newspaper Service. Published in the Sun 30th December 1976)

Cummings ‘I love red but not red carpets’ (Express Newspapers/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Daily Express 31st July 1981)

Kal on the Commonwealth (Kevin Kallaugher/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in Today 16th July 1986)

Johnston ‘Toe Sucking’ (News International Newspapers Ltd./John Frost Historical Newspaper Service. Published in the Sun 20th August 1992)

Franklin on the popularity of the Monarchy in Australia (News International Newspapers Ltd./John Frost Historical Newspaper Service. Published in the Sun 29th February 1992)

Bell ‘Orff with her ring!’ (Steve Bell. Published in the Guardian 22nd December 1995)

Bell ‘The way ahead senior royals think tank’ (Steve Bell/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Guardian, 20 August 1996)

Cummings ‘I’m having a ghastly nightmare that the photographers stopped invading my privacy!’ (Mrs M. Cummings/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in The Times, 16th August 1997)

Griffin ‘The Queen of all our hearts’ (Express Newspapers/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in The Daily Express, 1st September 1997)

Gerald Scarfe ‘The Tidal Wave’ (Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sunday Times, 7 September 1997)

Unny on the Queen (The Indian Express (Bombay). Published in The Indian Express, 12th October 1997)

Trog on the death of Diana, Princess of Wales (Wally Faukes/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sunday Telegraph, 7th September 1997)

Gerald Scarfe on the Australian referendum (Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sunday Times, 7th November 1999)

Mac ‘So Sophie. After that absolutely abysmal performance, you are the weakest link – goodbye’ (Atlantic/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Daily Mail, 9th April 2001)

Queen Elizabeth II 1926

FOREWORD

TO THE DIAMOND JUBILEE EDITION

Had Ben Pimlott been with us in the run-up to 2012, the print and electronic media would have made his telephone number and email the first to which they turned for a Diamond Jubilee assessment of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. To understand why is captured between these covers. The pages to come are the product of what happened when a leading political biographer and a top-flight historian of the twentieth century, the gifts combined in Ben’s person, took a long and serious look at the formation, the functions, the style and the adaptability of the lady whom we Brits of the post-war era were, and are, so fortunate to have as our Head of State.

Ben was naturally superb at calibrating the fluidities of our political and constitutional streams as they touched and occasionally refashioned the ancient banks of the Monarchy. He set the Queen’s reign in the context of all the wider changes to her UK realm on her road from 1952 – withdrawal from Empire; the long, reluctant retreat from great powerdom; our emotional deficit with Europe; a social revolution or two; and considerable changes in the size and make-up of our population. Through all these shifts, the Queen has been a gilt-edged constant who, in my judgement, has never put a court shoe wrong as a constitutional sovereign even though as a country we are entirely without a written highway code for Monarchy, relying on conventions and a constitution which, as Mr Gladstone wrote, ‘presumes more boldly than any other the good sense and good faith of those who work it’. Good sense and good faith are the prime requirements of a British and Commonwealth constitutional monarch and the Queen possesses both in abundance.

Ben Pimlott understood all this and illustrated it through all his pages, not one of which was dully written. He also had a sure touch when it came to the emotional geography of the wider landscapes where the Sovereign, the Royal Family and the people meet. He, for example, was the pilot we – and future historians – needed through the days and the swirls and the eddies that followed the death of Princess Diana in 1997. I have a suspicion that it was Ben who gave Alastair Campbell the description ‘the People’s Princess’ which the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, took up in his reaction to the tragedy in Paris. Ben was very good at mapping the Queen’s and the Palace’s recovery from the wobble in public esteem of September 1997. And it’s fascinating to think what Ben might have made now of the sixty-year spectrum of the Queen’s reign – of the self-restoring powers of the British Monarchy and of the enduring qualities of Queen Elizabeth which have always been a lustrous asset in tough times as well as the easier stretches in the life of her nation.

It is always difficult to winnow out the personal premium from the good standing of the institution of Monarchy (there are usually two-thirds of those polled in the United Kingdom in favour of it). The Queen came to the throne at a time when we were dripping with deference as a society. We are scarcely moist now. Yet the esteem for the Queen remains. As Head of State, she has always enhanced the great office she holds. The same cannot be said of others – not least some of those who have held the headship of government as Prime Minister in No. 10 Downing Street. And one scans the world in vain for another sixty-year example of faultless public duty. The Queen could not have had better personal trainers than her father, King George VI, and her mother, Queen Elizabeth. But, in sporting terms, it’s as if she had won gold at every Olympics from Helsinki in 1952 to London in 2012.

Ben Pimlott, too, won gold by writing this book and gold standard it will remain. For I will be surprised if, when the Queen’s official biographer is appointed, it’s not Pimlott on Elizabeth II that’s the first book for which he or she will reach on the shelf.

Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield, FBA

Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History

School of History, Queen Mary, University of London

LondonMarch 2012

FOREWORD

TO THE GOLDEN JUBILEE EDITION

In my Preface to the paperback edition of The Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth II, published a year after the hardback, I excused myself for not adding new material by saying that ‘an extra chapter would be part of another book’. I meant that any historical account is a snapshot, not just of its subject matter, but of the attitudes of the author when it is written. In this sense, The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy is another book. The first edition of The Queen was researched and written in the mid-nineties. It appeared in 1996, the year of the divorce of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and doubtless reflects that timing. This Golden Jubilee edition has been prepared several years later. It contains not one additional chapter, but five. The result is a book which has an altered shape from the original, while at the same time offering in the extra chapters a different snapshot.

Chapters 1 to 23 are little changed. There are a few corrections and stylistic tightenings, but I have not attempted to revise my interpretation. The new material is contained in Chapters 24 to 28. Here I have examined post-1996 events and sought to place them in the context of the Queen’s life and reign as a whole. I have also looked more closely – partly in the light of ‘Diana week’ – at aspects of the Monarch’s role that go beyond the purely constitutional or symbolic. If there is a new theme, it has to do with the ancient (but also apparently continuing) concept of ‘royalty’. At the same time, I have tried to integrate the added chapters so that the reader who comes to the book afresh can take it as a single work, and move from old to new without too great a sense of the division. The revised title is intended to indicate the shift in the book’s centre of gravity, and also to distinguish this edition from earlier ones.

I have included the original (hardback) Preface, and I would like to repeat my thanks to the people listed there, many of whom have been re-interviewed or who have given help with this edition in other ways. In particular, I would like to record my unique debt to the late Lord Charteris – a great royal and public servant with whom I spent many happy, instructive and sometimes hilarious hours in the cell-like interview rooms of the Palace of Westminster, and whose voice I often used to illuminate my text. In addition, I should like to thank the staff of the Buckingham Palace press office, and especially Geoff Crawford and Penny Russell-Smith, successively Press Secretaries to the Queen; together with Mary Francis, Peter Galloway, David Hill, Stephen Lamport, Robin Ludlow, Lady Penn, Frank Prochaska and a number of others who prefer not to be named. I should once again like to give my special thanks to Arabella Pike of HarperCollins, for her encouragement and ever incisive advice. I should also like to thank Aisha Rahman for her care and efficiency in guiding the Golden Jubilee edition through to publication. Caroline Wood has again provided invaluable help as picture researcher. At Goldsmiths, I am extremely grateful to Edna Pellett for typing an illegible (sometimes even to the author) manuscript with astonishing skill and without reproach. I would also like to thank Jef McAllister, London Bureau Chief of Time Magazine, and the staff at the Australian High Commission, for their kindness in providing access to newspaper and other files; and Dan and Nat Pimlott for their resourcefulness in sifting through them.

New Cross, London SE14 September 2001

PREFACE

‘What a marvellous way of looking at the history of Britain’, said Raphael Samuel, when I told him about this book. Others expressed surprise, wondering whether a study of the Head of State and Head of the Commonwealth could be a serious or worthwhile enterprise. Whether or not they are right, it has certainly been an extraordinary and fascinating adventure: partly because of the fresh perspective on familiar events it has given me, after years of writing about Labour politicians; partly because of the human drama of a life so exceptionally privileged, and so exceptionally constrained; and partly because of the obsession with royalty of the British public, of which I am a member. Perhaps the last has interested me most of all. To some extent, therefore, this is a book about the Queen in people’s heads, as well as at Buckingham Palace. It is, of course, incomplete – no work could be more ‘interim’ than an account of a monarch who may still have decades to reign. However, because the story is still going on with critical chapters yet to come, it is also – more than most biographies – concerned with now.

It is an ‘unofficial’ study, and draws eclectically on a variety of sources. For the period up to 1952, the Royal Archives have been invaluable; documentation up to the mid or late 1960s has been provided by the Public Record Office and the BBC Written Archive Centre, alongside a number of private collections of papers, listed at the end of this book. For later years, interviews have been particularly helpful. In addition, there is a wealth of published material.

I have a great many individual debts. I am extremely grateful to Sir Robert Fellowes (Private Secretary to the Queen and Keeper of the Royal Archives, Charles Anson (Press Secretary to the Queen), Oliver Everett (Assistant Keeper of the Royal Archives) and Sheila de Bellaigue (Registrar of the Royal Archives) for assisting with my requests whenever it was possible to do so.