Полная версия:

The Secret Wife: A captivating story of romance, passion and mystery

Copyright

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Gill Paul 2016

Gill Paul asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Image of the Romanov family used in the Historical Afterward courtesy of the Library of Congress

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008102142

Ebook Edition © June 2016 ISBN: 9780008102159

Version: 2018-06-05

Praise for The Secret Wife

‘Meticulously researched and evocatively written, this sweeping story will keep a tight hold on your heartstrings until the final page’ Iona Grey

‘A marvellous story: gripping, romantic and evocative of a turbulent and fascinating time’ Lulu Taylor

‘Just magical. At the last line, tears rolled down my cheeks. Highly recommended’ Louise Beech

‘A heart-warming affirmation of the tenacity of human love’ Liz Trenow

‘Gill Paul has clearly done her research in this absorbing story that cleverly blends imagination with historical fact. The closeted and ultimately doomed Romanov family have always fascinated, especially the four grand duchesses, and the older strand of this dual narrative story is told by one of the girls’ secret loves. Tragic, touching and authentic-feeling’ Kate Riordan

‘This is an intriguing and involving book that explores a really fascinating period in time in a clever and highly enjoyable way. I was hooked into both timelines from the start’ Joanna Courtney

‘A beautiful and moving story, beautifully and movingly told. I read it in just two sittings … I enjoyed every page’ John Julius Norwich

Praise for Gill Paul’s other novels

‘A marvellous moving adventure, full of vivid colour and atmospheric detail’ Lulu Taylor

‘A stunning epic’ Claudia Carroll

‘A terrific adventure story, full of romance and atmospheric detail – a great escapist read’ Liz Trenow

‘A gripping historical read … with an ending which is at once uplifting and heartbreaking. I couldn’t put it down’ Julia Williams

‘A wonderful story of love, romance, bravery’ One More Page

‘A love story that will squeeze your heart tight – this is the perfect all-consuming summer read’ Random Things Through My Letterbox

‘I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book … Brilliantly written, with great descriptions about places and events’ Boon’s Bookshelf

‘It is full of emotions and so many details, but the details are described in a wonderfully colourful, engaging way … Brutally honest, and I can only imagine how much thorough research went into writing this book’ I Heart Chick Lit

‘A wonderfully imagined peek into the fabulous excesses of the Burton-Taylor relationship, from booze-fuelled spats to their intoxicating chemistry’ Hello magazine

‘A stunning new voice – I was hooked from the first sentence of the prologue. With beautifully drawn characters and sensitive detail – The Affair draws you in and you won’t want it to end. An accomplished, energetic, original new voice in fiction’ Kate Kerrigan

‘Loved Women and Children First. Interestingly it deals with the aftermath/guilt/angst of surviving Titanic – gripping read’ Chrissy Iley

‘A warm-hearted and engaging novel that breathes fresh life into the well-known tragedy of the Titanic’ Amanda Brookfield

‘Paul keeps the narrative up, making a virtue of pace’ Guardian

‘A sexy, pacy, thoroughly modern novel’ Ham & High

‘Enough twists and turns to keep even the most devious plotmaster turning the pages as rapidly as possible’ Middlesborough Evening Gazette

Dedication

For Richard, with love

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for The Secret Wife

Dedication

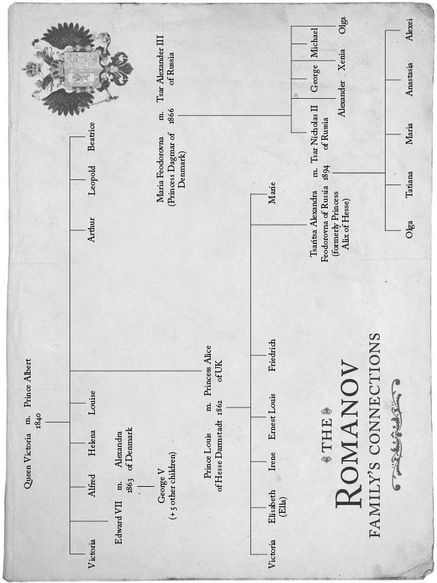

The Romanov Family’s Connections

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

Chapter Sixty-Seven

Chapter Sixty-Eight

Historical Afterword

Sources

Acknowledgements

Enjoyed This Book? Read on for the Start of Gill Paul’s New Novel, Another Woman’s Husband.

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

Lake Akanabee, New York State, 19th July 2016

It was twenty-nine hours since Kitty Fisher had left her husband and in that time she had travelled 3,713 miles. The in-flight magazine had said there were 3,461 miles between London and New York, and the hire car’s Sat Nav told her she had driven 252 miles since leaving the airport. A whole ocean and half a state lay between her and Tom. She should have been upset but instead she felt numb.

Back in the UK it was four-thirty on a Sunday afternoon and she wondered what Tom was doing, then grimaced as she pictured him pottering around the house in his jogging bottoms and t-shirt. He would no doubt have called her closest friends, all innocence, asking if they knew where she was. How long would it take him to work out she had flown to America to look for the lakeside cabin she’d inherited from her great-grandfather?

She had been careful not to leave any paperwork behind so he didn’t have the address. Let him stew for a while. It served him right for his infidelity. She shuddered at the word, an involuntary image of the messages on his phone flashing into her brain. She was still in shock. Nothing felt real. Don’t think about it; stop thinking.

The woman on the Sat Nav was comfortingly sure of herself: ‘In two hundred yards take a left onto Big Brook Road.’ It felt nice to be told what to do; that’s what she needed when the rest of her life was falling apart. But a few minutes later the voice-lady seemed to get it wrong. ‘You have reached your destination’ she said, but all Kitty could see was dense forest lining the road on either side. She drove further but the voice urged her to ‘Turn around’.

Kitty got out of the car to explore on foot and, peering through the trees, discovered a track overgrown with waist-high grass and hanging branches. She consulted the map that had been sent with the cabin’s ownership documents and decided this must be it. The car’s paintwork would get scratched if she tried to drive down so she set off on foot, pushing her way through the thicket. There was a droning of insects and a strong smell of greenness, like lawn cuttings after rain. Before long she could see the steely glint of Lake Akanabee, with pinpricks of light dancing on the surface. When she reached the shore she looked around, squinting at her map. The cabin should have been right there.

And then she noticed a mound about twelve feet tall, camouflaged by creeping plants. It was thirty years since anyone had lived there and Kitty was prepared for the cabin to be reduced to a pile of rubble. Instead it was as if the forest had created a cocoon to protect it from the elements. Weeds wrapped themselves around the foundations, pushed in through broken windows and formed a carpet over the roof. The entrance was barely visible through a mass of twisted greenery. But the cabin’s location, nestled on a gentle slope just yards from the pebbly shore, was stunning.

She walked over to look more closely. A jetty sticking out into the lake had long since collapsed, leaving a few forlorn struts. A sapling had grown up through the four or five steps to the cabin’s porch, causing them to buckle and snap, and its roots tangled through the fractured wood like a nest of snakes. But the corrugated steel roof appeared to have stayed watertight, protecting the walls beneath. ‘Concrete foundations,’ she noted.

Treading with care, Kitty climbed onto the porch, where rusty chains hanging from the ceiling and some fractured planks on the floor indicated there had once been a swing seat. She imagined her great-grandfather sitting there, looking out at the view, perhaps with a beer in his hand. Pushing aside the foliage, she reached the cabin door and found it wasn’t locked. Inside it was dim and musty, with a smell of damp mushrooms and old wood. Dust motes danced in shafts of light pouring through gaps in the creepers. When her eyes adjusted, Kitty saw there was one large room with a rusty stove, an old iron bed topped by a mouldy mattress, a wooden desk, and heaps of rubbish everywhere: yellowed newspapers, ancient cans of food and a pair of perished rubber galoshes.

She stepped carefully across the room. Through a doorway there was a bathroom with a stained tub, basin and toilet; a cobweb-covered shaving brush nestled on a shelf. To her astonishment, the toilet flushed when she pulled the handle, and after a low creaking sound dark water came out of the tap. She guessed they must be hooked up to a water source on the hill behind and that there was a below-ground septic tank, but it must be at least thirty years since that tank was last emptied.

She turned back into the bed-cum-sitting room and walked around, checking the condition of the walls and ceiling. Thankfully the floor held firm underfoot. She reckoned she could even stay the night once she’d cleared the rubble and torn back the jungle to let in some air.

Out on the porch she took in the view. A couple of silver birch trees stood between her and the beach, which was lapped by tiny waves. No signs of human habitation were visible, and no traffic sound intruded; the opposite shore about a mile away was thick with forest. It was just her and the trees and the lake, and it was glorious.

Kitty walked back to the car to retrieve her bags and drag them down the track, flattening the grass in her wake. She ate a salt beef and gherkin sandwich from the selection she had bought at the airport, drank a can of Seven-Up, then donned some sturdy gloves to start tearing at the creepers that smothered her cabin. Already it felt like hers, she noted. Already she was falling in love with it.

One of the plants was what she and her school friends called ‘sticky willy’. They used to try and stick it on each other’s backs without being noticed. Another type of creeper filled the air with spores that tickled the back of her throat. She was careful not to let any leaves touch her skin because she knew they had poison ivy in America but she wasn’t sure what it looked like. A swarm of tiny black flies rose into the air and floated away in the breeze. She worked with grim determination, hoping that by totally exhausting her muscles she could quell the panicky thoughts that clamoured in her brain. Don’t think about Tom. Stop thinking. She had brought her mobile phone and laptop through force of twenty-first-century habit, but both were switched off. She couldn’t bear to listen to his excuses and self-justifications, simply didn’t want to deal with any of it.

When she had yanked back most of the overgrowth, she saw that the weathered wooden slats made the cabin look like an organic part of the wooded landscape. Despite having just one room it was big, perhaps twenty feet long, with windows all around, and the sloping roof had a little chimney sticking out. She went inside again and loaded debris into some heavy-duty bin bags she’d brought along, stopping to read a few yellowed news headlines: the accident at the Chernobyl power plant in Russia; the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle. The springs on the bed had long gone, so she hauled it outside to dispose of later then unrolled the sleeping bag she had brought and spread it in one corner.

By the time she finished, the sun was lowering over the lake and birds were squawking loudly, expending their final burst of energy for the day. She went to sit on the porch to listen. A whip-poor-will called, and it sounded for all the world like a wolf whistle. Shadowy bats zipped by, and frogs croaked in the distance.

Suddenly she saw something glint under the fractured wood of the steps, nestled amongst the tree roots. She lay down full length stretching her arm to grasp it and was immediately surprised by the weight of the object. She pulled it out and saw it was a golden oval, less than an inch long, studded with tiny coloured jewels – blue, pink and amber – set within swirls of gold tendrils, like flowers on a vine. It looked expensive. On the back she could make out some scratched engraving but it had been rubbed away over the years. There was a hole in the top and she assumed it had been threaded on a chain. Someone must have been upset to lose such a stunning pendant. She’d never seen anything quite like it.

Kitty slipped it deep into the pocket of her jeans and opened another airport sandwich, turkey and salad this time. She ate it for supper, washed down with a miniature bottle of Chenin Blanc she’d brought from the plane, as she sat with her legs dangling off the edge of the porch. In front of her, the trees swayed in a slight breeze and the smooth surface of the lake reflected the dramatic colours of the sky, changing from pale pink to mauve to gold and then bronze, as vivid and surreal as the painted opening title shots of a Hollywood movie.

Chapter One

Tsarskoe Selo, Russia, September 1914

Dmitri Malama drifted to consciousness from a deep slumber, vaguely aware of murmuring voices and the whisper of a cool breeze on his face. He had a filthy headache, a nagging, gnawing pain behind the temples, which was aggravated by the brightness of the light. Suddenly he remembered he was in a hospital ward. He’d been brought there the previous evening and the last thing he recalled was a nurse giving him laudanum swirled in water.

And then he remembered his leg: had they amputated it in the night? Ever since he’d been injured at the front he’d lived in fear that infection would set in and he would lose it. He opened his eyes and raised himself onto his elbows to look: there were two shapes. He flicked back the sheet and was hugely relieved to see his left leg encased in bandages but still very much present. He wiggled his toes to check then sank onto the pillow again, trying to ignore the different kinds of pain from his leg, his head and his gut.

At least he had two legs. Without them he could no longer have served his country. He’d have been sent home to live with his mother and father, fit for nothing, a pitiful creature hobbling along on a wooden stump.

‘You’re awake. Would you like something to eat?’ A dumpy nurse with the shadow of a moustache sat by his bed and, without waiting for an answer, offered a spoonful of gruel. His stomach heaved and he turned his head away. ‘Very well, I’ll come back later,’ she said, touching his forehead briefly with cool fingers.

He closed his eyes and drifted into a half dream state. He could hear sounds in the ward around him but his head was heavy as lead, his thoughts a jumble of images: of the war, of his friend Malevich shot and bleeding on the grass, of his sisters, of home.

In the background he heard the tinkle of girlish laughter. It didn’t sound like the plain nurse who had tended him earlier. He opened his eyes slightly and saw the tall, slender shapes of two young nurses in glowing white headdresses and long shapeless gowns. If he’d just awoken for the first time in that place, he might have feared he had died and was seeing angels.

‘I know you,’ one of the angels said, gliding over to his bedside. ‘You were in the imperial guard at the Peterhof Palace. Weren’t you the one who dived into the sea to rescue a dog?’

Her voice was low and pretty. As she came closer, he realised with a start that she was Grand Duchess Tatiana, the second daughter of Tsar Nicholas. While Olga, the eldest, looked like her father, Tatiana had her mother’s faintly oriental bone structure. She was gazing at him with intense grey-violet eyes, waiting for an answer.

‘Yes, I’m afraid that was me. My uniform was ruined, my captain was furious, and the dog was a stray who shook himself down and ran off without so much as a thank-you.’ He smiled. ‘I’m surprised you heard about it, Your Imperial Highness.’

She returned his smile. ‘I heard some guards discussing it and asked them to point you out. You must be a dog lover.’

‘Very much so. I have two at home, a Borzoi and a Laika. They’re scamps but I miss them terribly.’