скачать книгу бесплатно

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN OF RUSSIA

OF 1941-1943

AND ITS MEMORY

I’ve still in my nose the smell of grease on a red-hot machine-gun. I’ve still in my ears and even in my brain the crunching of snow under my boots, the coughs and sneezes from Russian lookouts, the sound of dry grass swept by the wind on the banks of the Don. I’ve still in my eyes the stars of Cassiopeia which hung above my head every night, and the bunker props above my head every day. And when I think about it all I feel the terror of that January morning when their gun Katiuscia first let off its seventy-two rocket-shells.

This is the incipit of a famous autobiographical novel, The Sergeant in the snow, written by the Alpine Mario Rigoni Stern, soon destined to become the best-known literary testimony of the disastrous Italian campaign in Russia during the Second World War.

When, in June 1941, Hitler decided to wage war against the Soviet Union, triggering Operation Barbarossa, Mussolini responded by offering his willingness to support the German troops. The establishment of a Corps of Italian expedition to Russia (CSIR) left in mid-July for the eastern front under the orders of General Giovanni Messe.

The following year, combined with new corps in the Armir (Italian Army in Russia), it was deployed on the Don and couldn't resist the Soviet offensive that, between December 1942 and January 1943, would have decimated it. Numbers show the extent of the disaster.

Out of 230,000 Italians who left for the eastern front, one-third of these – about 95,000 – had lost their lives: dying in combat, dying of hardship and cold, during the retreat or the stages of transfer to the prison camps, sadly known as Davaj marches (from the term used to solicit the passage by the Russian escort soldiers). Without forgetting how many perished during the same imprisonment and the high number of those missing.

An event so fatal and fraught with consequences for thousands of Italian soldiers – swallowed up by the Russian steppe, plagued by tough Soviet resistance, as well as by adverse climatic conditions – and for their families, often destined to remain unaware of the fate of their relatives, ended up feeding a copious memoir, stimulated by the desire to account for a unique and devastating experience.

It is no coincidence that the Russian campaign – as the historian Maria Teresa Giusti, author of a valuable volume on the subject, pointed out – ended up as “one of the twentieth-century war events with the biggest impact on Italian collective memory”

.

A memory that is certainly uncomfortable, on the one hand, if we consider the fact that the war campaign was still an expression of the aggressive policy of Mussolini, but so disruptive due to the suffering and dramatic conditions of the retreat as to reveal the profound disillusionment with the regime. The bitter acknowledgment of the lack of training marked the participation of the Italian soldiers in the enterprise, which was opposed by the undoubted acts of heroism of those who were lucky enough to survive that terrible experience and return home. In this regard, it is interesting to re-read the authoritative testimony of another veteran, Nuto Revelli, among the first to denounce the dramatic conditions of the soldiers on the Russian front in his memorial writings:

Everything was unsuitable for the environment. Even the uniform, so green, made us targets. We had wagons of mountain warfare equipment, from ice crampons to avalanche ropes and rock ropes.

We were Alpine soldiers made for slow warfare, for walking. We had 90 mules for each company and four lorries for the whole battalion. Our weapons consisted of the Model 1891 rifle that had one advantage for its age: it was not muzzle loading. The equipment for the department was the Breda machine gun, which fired when well cleaned and oiled. We couldn’t, however, fire too many volleys, lest the barrel turned red, or the gun jammed, or fired on its own. The accompanying weapons – Brixia mortars, Breda machine guns, 81 mortars, and 47/32 cannons – were, for the most part, outdated and, in any case, not enough. Our only anti-tank weapon – the 47/32 cannon – could only pierce Italian tanks. Against Russian tanks, there was nothing to do.

Artillery in the divisional area consisted of museum equipment: the 75/13, the 100/17, utterly harmless and safe hand grenades, which did not always explode.

Means of a connection made for mountain warfare, unsuitable for long distances; the old faded flags, the heliographs, were of no use on that undulating terrain. The few radios, heavy and battered, were sometimes less fast than the order carriers.

No mines, no flares, no reticulates, no tracer bullets. And little ammunition, almost depleted.

The equipment was the same as on the Western Front from the battle of June 1940. Uniforms made of the worst wool, shoes of stiff, dry leather that looked like paper. The foot cloths seemed to have been made on purpose to block the blood circulation, favouring heating or freezing.

We were not tanks. We were mountain troops, poorly armed, poorly equipped for mountain warfare. Throwing ourselves into the plains, where armoured warfare was running fast, meant going in blind.3

Historiographical research confirmed it was a disaster. A disaster made worse by the grave shortcomings of the Italian army's war equipment and the laxity with which the military commanders and Mussolini approached the enterprise.

The Duce was sure that the war would be over soon, mainly due to the training and firepower of the German ally. Therefore, he had refrained from mobilising the country for the campaign – as had happened during the conquest of Ethiopia. The affair resulted in the worst collapse suffered by the Italian army.

To be fair, you must not overlook the fact that the image of the victimized condition of the Italian soldier, in the transmission of the memory and subsequent representation of the event, would have been overshadowed, concerning the criminal policy of the regime, the cruelty of the Red Army and the harsh weather conditions.

Not to mention the often-cited lack of support from the German ally: the offensive and not defensive nature of the war, the Italian army seen as a full-fledged invader against a country that tried to defend itself strenuously against the occupation policy pursued by the Axis powers.

Beyond the reasons and responsibilities for the conflict – to keep in mind to avoid supporting a distorted and “mythical” vision – memories of that traumatic war campaign had a powerful effect on the survivors’ minds, leaving us some of the most intense pages about the Italian war, full of strong impressions, pathos, horror, and titanism.

As Maria Teresa Giusti has also pointed out, it is no coincidence that the accounts relating to the military experience in Russia, within the framework of the memories of the Second World War, have been far more than all those dedicated to the other fronts.

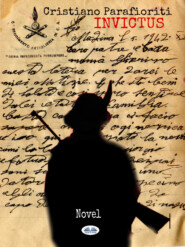

The Russian campaign is the background of Invictus, a historical novel. The novel is the processing of the experience lived by a young Sicilian peasant, originally from a village in the Nebrodi municipality of Galati Mamertino, in the province of Messina, who went to war on the eastern front. We face a memory handed down from generation to generation, at first known only by the family, then entrusted – after a long period of detachment from those events and sedimentation – to the pen of a talented writer and fellow countryman, Cristiano Parafioriti. He managed to give vigour and substance to the narration of that extreme experience, to the point of making it an abiding testimony of the struggle of men to preserve their humanity in the face of the destructive horde and horrors of war.

In a grand choral fresco, the novel tells the story of a Sicilian farmhand, Salvatore, known as Ture, the eldest son of the Di Nardo family. Although his father, who had already experienced the tragedy of the Karst during the First World War, tried to save his son from this ominous prospect with various pressures and expedients, Ture could not avoid military service and be called up for war.

The fate reserved the worst of destinations for him: the Russian steppe.

Accustomed to sacrifices, to harsh winter in the mountains, shaped by the hard life in the fields, he managed to survive the rigours of a campaign, living in prohibitive conditions. And to return to his beloved land, not without further risks and adventures, knitting back the threads of affection that the war had threatened to interrupt forever.

Taken from the treasure chest of memory, in the frame of a historical novel that edits and enriches but does not alter the truth – if anything, in some cases, it transcends it – the story of the main character Ture Di Nardo becomes exemplary of the condition of many farmers. They often are the only support for their families but are torn away from their work and affections. They are thrown into a sort of no man’s land, the battlefield, dominated by anonymous and mass death, at the mercy of a war that brutalises and, in some ways, depersonalises them.

The narrative represents well the perspective from below, of those peasants from the most remote areas of the country suddenly catapulted into a hellish conflict, ruled by resignation and frustration and by a substantial indifference towards the reasons for the war, experienced at like a natural disaster. The protagonist’s attitude in the novel reflects the conditions of that rural world accustomed to patient sacrifice, which struggles to identify with the State and whose dimension still lived the local, municipal one. Far from the ideas of power and greatness promoted by the regime, averse to fascist myths, far from the exasperated patriotic spirit nurtured at that time, Ture found himself immersed in the tragic reality of the Italian war on the eastern front. The only comfort offered by solidarity with his comrades in arms and the faint hope of one day being able to return home to fulfil his love dream with his beloved Rosa.

The novel gives us an extraordinary cross section of the physical and mental universe, of the values, fears, needs, and aspirations of peasant families in a mountain area – the Nebrodi area: the hard work in the fields, made of toil, sweat, and abuses perpetrated by a class of landowners, of noble origin, who still in the first half of the 20th century firmly held possession of most of the land, profiting handsomely by renting it out, often with random criteria.

Parafioriti’s realist prose is fluid and easy to read, in the best Sicilian literary tradition. He thickens the narrative plot as he follows the development of the love affair between Ture and his cousin Rosa, with the twist of events and circumstances reminiscent of Manzoni that hinder its full completion.

He deals efficiently with the various characters, captured in their intimate essence, creating an impressive social fresco based on solid historical knowledge and appropriate use of language.

After the short stories of Era il mio paese (2014), Sicilitudine (2016), and the transition to the historical novel with D’Amore e di briganti (2019), set in the post-unification period of the nineteenth century, this new literary effort marks the author's arrival at a test of definite maturity, with an organic novel able to hold the reader's attention by the force of the story and its universal value. All Parafioriti’s writings have a common denominator, an unmistakable common thread: they express a deep connection with his homeland in Sicily, Galati Mamertino and its hamlet of San Basilio, on the Nebrodi mountains, which becomes an integral part of the characters the author narrates. From this context, the novel events unfold to fit into the broader framework of the history of the twentieth century.

In conclusion, it seems accurate to reflect on the genesis and scope of this work to recall the following observation:

“Every human being is unique, an unrepeatable being who, however much he may run about in the dark, mixing accidents with his intentions, never follows in the footsteps of another, never repeats the same path, never leaves behind the same story. This is another reason why life stories are told and listened to with interest, because they are similar and yet new, irreplaceable and unexpected, from start to finish.”

As Hannah Arendt pointed out, “no one has a life worthy of consideration of which a story cannot be told”

. By recounting the cruel reality of war, the author tries to emphasise and exalt the unparalleled nature of each human destiny but also the eternal, exceptional value of the testimony of suffering and dignity capable of overcoming the barrier of time and projecting itself into today’s world. In the hope that memory can always represent – in the words of Liliana Segre – a precious vaccine against indifference.

Prof. Antonio Baglio

(Università degli Studi di Messina)

PART I

I

Village of San Giorgio, April 1941

Nebrodi mountains

Zi

Peppe Pileri would go back from the countryside in the evening. The days were getting longer, and he tried to make the most of every last ray of sunshine. Thus, just before retiring, he would pluck the last dry twigs from the ground and pile them up in the corner with the rest, load up the sack with the day’s harvest, and, with a broom rope, put a few pieces of dry wood on the mule to fuel the fireplace.

It was early April, and the cold was still being felt, especially within the stone walls of the small village of San Giorgio, where Zi Peppe lived with his family. There, the gusts of mistral blew in the nights while the foxes and martens ate the chickens. There was starvation, and now there was also war.

Zi Peppe Pileri had to provide for his family, consisting of seven children, and there was never enough bread. He always said that he believed in God for heavenly things, but with earthly things, he needed luck, and to have it, you had to be born under a lucky star and, above all, escape the evil eye. Thus, every single evening, as soon as he reached the last houses of the large village of San Basilio, in a place called Bolo, before taking the rough mule track towards San Giorgio, he would dismount from the animal and stand on the opposite side of the houses. Then he would walk, almost rubbing the wall, trying to escape the gaze and the words of ‘Gnura Mena, the witch.

She was an uptight and grumpy woman who had lost her husband in the WWI and, since then, bitter for this harsh fate, she was said to cast the evil eye on other women’s husbands and children.

Everyone feared her.

That evening Zi Peppe Pileri thought he had dodged her, but he was wrong.

‘Gnura Mena was lurking at the edge of the trough, on the other side of the road, and he couldn’t avoid her.

“Peppe, is the day over?” the woman asked. “Yes, Mena, I’m retiring before it gets dark,” he cut in. “You know they still call a lot of boys to fighting in the war...” “I’ve already been to war with your dearly departed husband, Caliddo. They can’t call me anymore, Mena!” Zi Peppe said.

“Not you, but your son Ture can be!” “It will be God’s will, and God’s will will be done. Good night, Mena.” “God has forgotten us, Peppe,” was the harsh reply.

Zi Peppe digested the bitter words of the woman, but when the roofs of Bolo disappeared behind him, he stopped the mule and touched the iron under the hoof for good luck.

Damn witch, she is trying to jinx my son Ture!

When he arrived in San Giorgio, he put the beast back in the stable and went home for dinner. He wearily said hello to his family, ready for the evening meal, and sank into his chair, waiting for one of his daughters to come and serve him.

Concetta arrived. She was eighteen years old and already looked like a grown-up woman. She immediately became upset.

“You are stubborn, father! I told you that you should take off your boots full of mud outside the door!” Zi Peppe lowered his eyes. He was so absorbed in his thoughts that he had forgotten to take them off.

He apologized with a tired gesture of his fingers and brought a basin of hot water to clean at least his hands with a pumice stone because they were still dirty.

Concetta came back with a jug, filled the basin again, and with vigour, washed her father from the feet up to the knees, then dried him with a cotton cloth, put on his woollen socks, and began to prepare the table for dinner.

Before eating his soup, Zi Peppe grabbed the bread to cut it. He wanted to dunk a few pieces into the steaming broth, but while he was about to swallow the first bite, his wife, Za Nunzia, scolded him back:

“Peppe, you forgot to mark the bread with the cross before cutting it! What’s wrong with you? You’ve gone off the deep end! Don’t forget that the daily bread is God’s blessing!”

Zi Peppe sank the dripping spoon into his plate and looked up at Nunzia. “That old goat of Mena of Bolo cast the evil eye on me!”

“I can’t believe it... do you still believe in curses?”

“Shit, Nunzia, you still believe in priests, don’t you? And I believe in curses!”

“Don’t swear in front of the kids, and don’t insult the Church, as usual! And what curse did that poor woman cast to you? Let’s hear it…”

“She told me they’re calling soldiers to the war and that Ture might be…”

“That motherfu–” Nunzia winced, covering her mouth before uttering other insults.

“Tomorrow, if I see her at the trough, I’ll tell her off! She must leave my son Ture alone!”

Zi Peppe appeased her, and they both ate the last meal of the day in silence. It was a great relief that, at least for that evening, at the table, Ture was not there. He had gone to work for a week in Bronte.

After dinner, the whole family said a Hail Mary and prepared to rest.

Nunzia picked up a blanket hanging over the fire pit, laid it on their children’s bed to give them some warmth, and then returned to her husband. They chatted and promised each other not to pay too much attention to Mena’s words.

It was past midnight, but Zi Peppe could not sleep. He heard everything: the barking of Zi Dimonio’s dogs, the creaking gate of Zi Natale Sponzio’s henhouse, and, almost, even the river slowly flowing downstream. Above all, the words of Mena were still in his mind. Maybe the woman had never forgiven him for having survived her husband, who had also been on the Karst during the First World War. He turned towards Nunzia, seeking comfort from her body beside him. But in the pitch dark, even his wife’s eyes shone like stars.

That night, the Pileri could not sleep.

II

Zi Peppe Pileri often repeated that he had already lived two lives. About his first life, he told little and reluctantly. He referred to his harsh childhood, the troubles of his adolescence, and the subsequent tumultuous events that had involved him.

Of all of them, the memory that troubled him most was when, as a conscript, he was on patrol at the Camaro Infantry Regiment on 28 December 1908.

At dawn on that day, Messina was destroyed by an earthquake and seaquake. He survived by a miracle. The barracks had imploded in a few moments, and the ammunition storage area had blown up. As luck would have it, he was on patrol along the outer perimeter and was thrown twenty metres by the shock wave. He had been deaf in one ear for fifteen days but could not benefit from any recovery because he was needed to shovel through the rubble of the devastated city.

After that event, he spent a month and a half among the corpses, and the memory of those few survivors being pulled out alive from the ruins of the massacre still made him flinch. At the time, the Command had taken care to send a dispatch only to the families of the dead soldiers; there was no news of the living. Moreover, Zi Peppe hadn’t heard anything about his family, whether the earthquake had affected the villages in the Nebrodi mountains.

Only in March 1909, when he had finished his military service, he returned to San Giorgio.

He had not even had time to rejoice at the safe return of his loved ones when hunger and the crisis forced his father to embark him for America in May of that year.

After 29 days spent between Messina, Naples, and the Atlantic Ocean, he arrived in New York on 26 June 1909.

He was 20 years old and, arrived in the New Continent, had been admitted to the quarantine area of the Ellis Island Immigrant Reception Centre for a month because of suspected bronchopneumonia.

During those long days as a prisoner-sick man, he had met some shady Sicilian emigrants, who had hired him for some ‘special commissions’.

A few revolver shots he had dodged, a few others he had fired, and he had thus created a ‘respectable reputation’ for himself, thanks to his charisma and cleverness in smuggling whisky.

After six years, he was called up as a soldier in Italy because of the Great War. If he had stayed in America, he would have been considered a deserter and couldn’t have returned to Sicily any more.

Therefore, he had decided to return home, and, soon, young Peppe, from the charming and dangerous New York, found himself in the Cavalry Regiment Savoia on the Isonzo front.

He saw more dead people killed in one day on the Karst than in six years in New York!

When he returned, he carried the signs of war with him, and, suddenly, the American dream had vanished completely. The mere thought of returning to the Wild West that was America in the early 1900s made him shudder.

The Messina earthquake, the American mafia, the war, too much blood, and the too many deaths in so few years had worn him out.

He chose the quiet life of a farmer and decided to stay in San Giorgio.

There he began his second life.

A year after the end of the Great War, he met Nunzia and got married. Slowly, they began to cultivate the land, raise animals, and have children.

In November 1921, his first son, Ture, was born.

Ture was now 20 years old.

He was a bright and solid young man. As the eldest of the large family, he was, by right and by duty, the right-hand man of Zi Peppe Pileri, who had brought him up on hoe and bread from an early age.

Young Ture was meek, but not a few times he came home red with rage and fisticuffs. He never offended anyone, he was respectful towards his elders, and he didn’t let anyone push him around.